Latest Posts

Small business owners have faced a challenging year with a reduced walk-in customer base. However, the holiday season brings them hope, and CHM digital content producer Luiz Magaña has compiled a list of small businesses that are featured in our exhibition American Medina: Stories of Muslim Chicago. We hope you enjoy our shopping recommendations!

Watan

Jumana Al-Qawasmi opened Watan in 2015 in Orland Park, Illinois, with the aim to feature Palestinian-inspired art and to create a cultural space to connect both Muslims and non-Muslims to Palestinian heritage. Watan features clothing, jewelry, art prints, and accessories created by Palestinian artists.

Colettaa

Colettaa was founded in Chicago by Kadiatou Diallo right after she graduated from the International Academy of Design and Technology. Created and designed in Chicago, their collections are made for those who want beautiful, accessible, affordable, and ready to wear clothes. Colettaa’s goal is to create ideal, modest clothing without sacrificing quality or creative expression for young women.

The Hijab Vault

The Hijab Vault is a retail boutique in Lombard, Illinois, founded by Obaidullah Kholwadia and his sister that sells a variety of hijabs with modern prints, designs, and fabrics, as well as accessories.

Adilah M

Founded by Adilah Muhammad, Adilah M is a high-end, ethical fashion brand that produces well-tailored, small batch clothing. The garments are made and produced responsibly in the United States by people of color to create modern silhouettes for empowered women.

Imani’s Original

The origin of the bean pie dates back to the 1930s when Nation of Islam founder Elijah Muhammad outlined a set of lifestyle guidelines to his followers, which promoted the health benefits of the navy bean. While working on a home school project with her daughter on the benefits of the navy bean, Imani Muhammad started her company, which has been a family-run corporation since 2005. You will find her pies in more than fifteen stores in the Chicago area and shipping is available throughout the country.

Home Line Decoration

After losing his home and store in Puerto Rico to Hurricane Maria in 2017, Yousef Barakat and his wife, Kholoud Ghaith, decided to start fresh in Chicago. Home Line Decoration opened in 2018 in the Portage Park neighborhood and features specialty hand-made products from Turkey such as rugs, dinnerware, and Ottoman-style mosaic lamps.

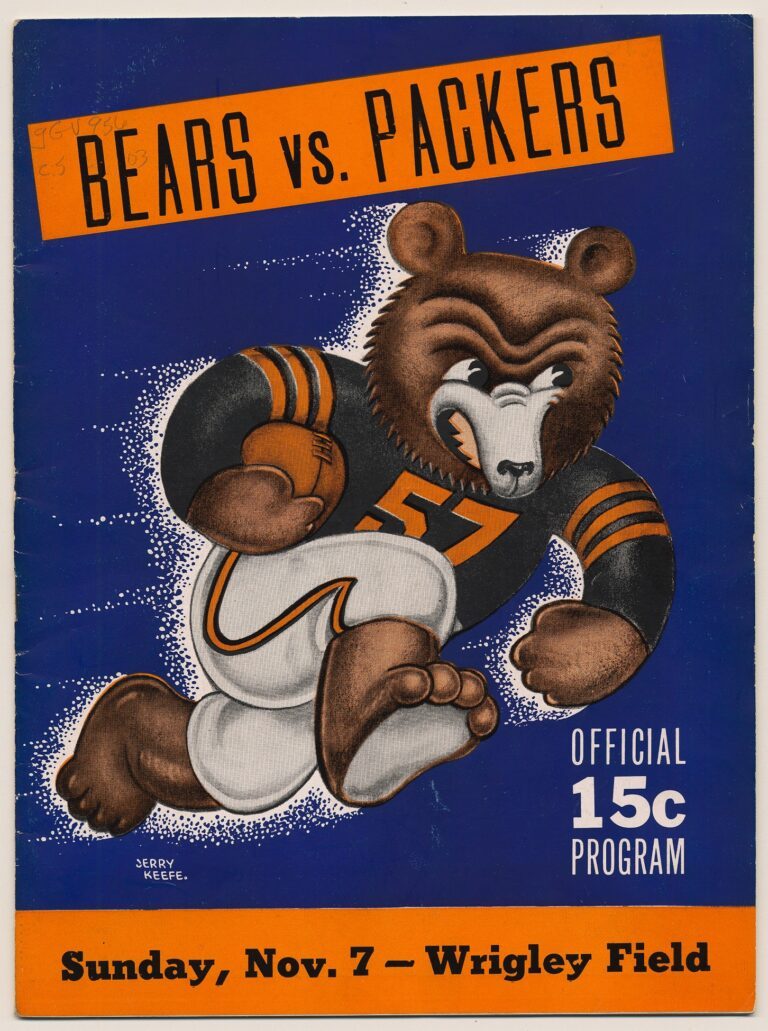

The Bears and the Packers have one of the longest-standing rivalries in the NFL and the league’s most played. Their first meeting was in 1921, when the Bears, then known as the Chicago Staleys, defeated the Packers in a 20–0 victory—the start of a century-long conflict.

Front cover of Nov. 7, 1943, Bears vs. Packers program, CHM, ICHi-059811.

The Bears and Packers have been in the same conference since the NFL switched to a conference format in 1933, first in the Western Conference and then in the NFC North since 1970, and usually play each other twice a year. They have met 200 times in regular- and postseason games. In recent years, the Packers have taken over the lead in the series with a 99–95–6 record.

Aerial view of Wrigley Field during the Bears vs. Packers game, Nov. 17, 1963, ST-17500877, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM.

Notable Bears wins over the Packers include their second meeting of 1963 (in the aerial shot above), with both teams coming to the game with 8‒1 records and playing for first place in the conference, and their October 21, 1985, win in which rookie defensive tackle William “The Fridge” Perry was put in at fullback and scored his first touchdown. Both seasons would end with the Bears as national champions.

Linebacker Mike Singletary (#50) during the game at Lambeau Field, Oct. 11, 1989, ST-20000203-0007, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM.

Notable losses include the infamous “instant replay game” in 1989 (seen in the collage above), when a Packer touchdown was credited after instant replay overruled a penalty called on quarterback Don Majkowski for stepping over the line of scrimmage, and the teams’ last playoff meeting in the 2010 NFC championship.

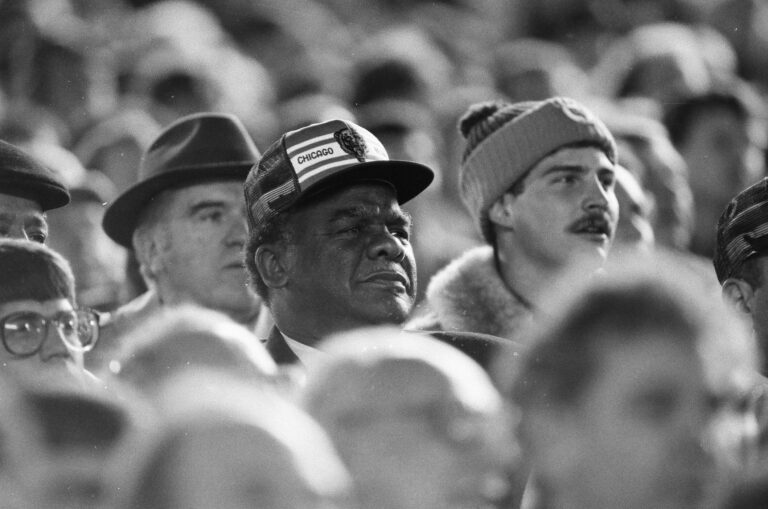

Mayor Harold Washington in attendance at Soldier Field, Oct. 21, 1985, ST-20001960-0077, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM.

Look back at 100 years of Bears history on our blog.

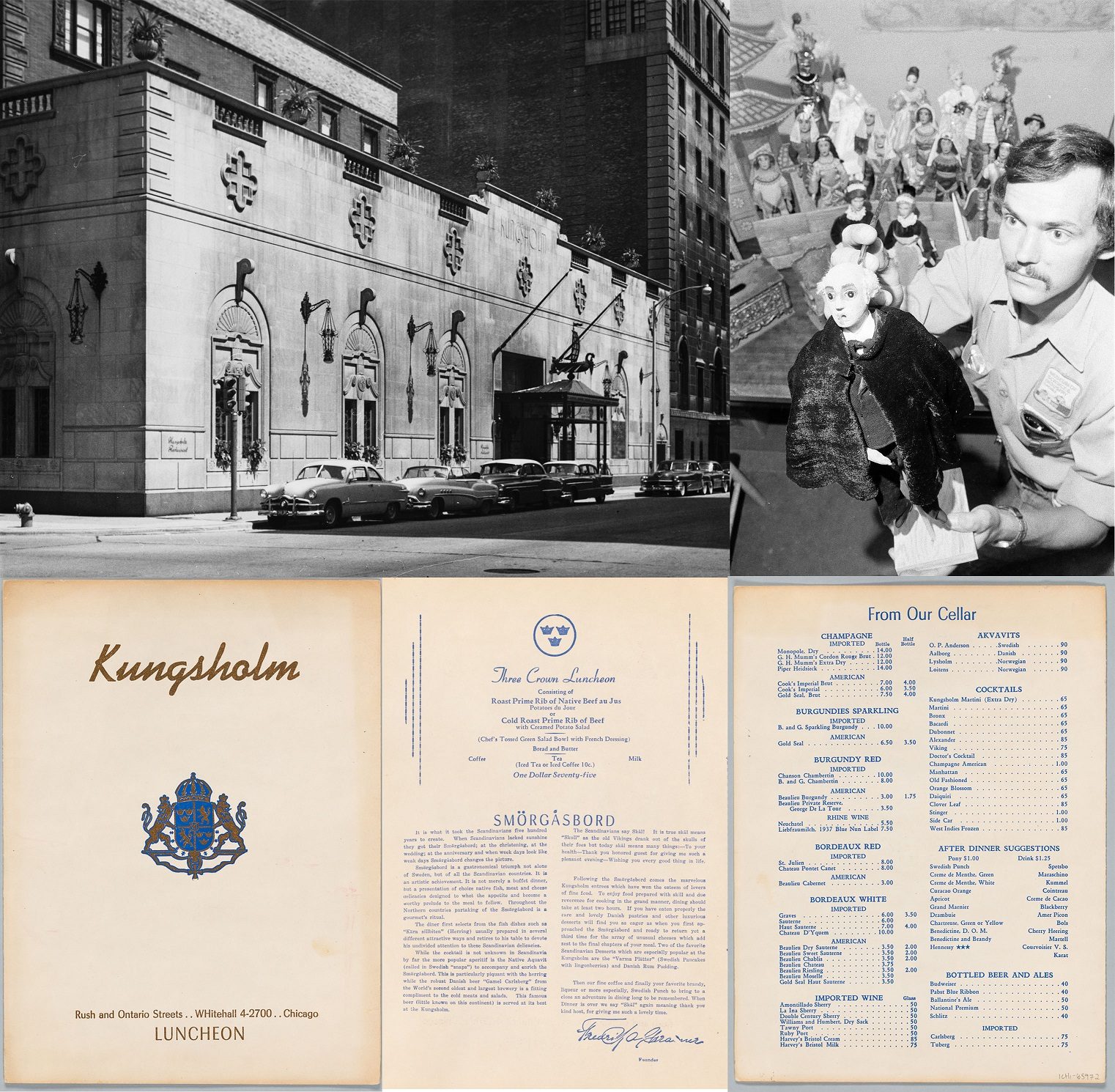

With the news that Lawry’s The Prime Rib will be closing at the end of the year, we can only wonder if the next tenant of the former McCormick Mansion will also make a name there. Let’s revisit another establishment that has left a legacy at the corner of Rush and Ontario Streets. From 1937 to 1971, 100 East Ontario Street was home to the Kungsholm, a one-of-a-kind Scandinavian restaurant that was famed for both its food and entertainment.

Danish-born Chicago restaurateur Fredrik Chramer took over the building in 1937, adding significant square footage and a commanding facade and remodeling the interior in Swedish Modern style. Patrons were greeted by Swedish and American flags and a model Viking ship above the entrance, and the motif of three crowns, the national emblem of Sweden, appeared on the menu and in decor. A large table in the center of the main dining room was laden with items from the three traditional stages of smörgåsbord dining: herring and seafood; hot entreés, such as Kalvfilé Oscar (veal tenderloin with shrimp and asparagus tips covered by béarnaise sauce); and salads and cheeses, followed by dessert and coffee or wine.

In 1940, inspired by the puppet shows he loved as a child in Denmark, Chramer turned the mansion’s fourth-floor ballroom into what would become the internationally known Kungsholm Miniature Grand Opera. Throughout the years, more than a million people were entertained by his unique thirteen-inch-tall handcrafted stringless puppets performing elaborately staged operas, operated by puppeteers on rolling stools beneath the floor.

A fire destroyed the theater in 1947, but Chramer rebuilt it five years later as a new puppet theater modeled after the Opéra Garnier in Paris. As Chramer’s health started failing, he sold Kungsholm and the show to the Fred Harvey chain in 1957. The new owners did not maintain the production quality, and business declined. The Kungsholm puppet opera closed its curtains for good in 1971, and the Chicago History Museum managed to acquire some of the puppets and scenery.

Trace the city’s evolution from meatpacking capital to foodie paradise through our Google Arts & Culture story: Touring Chicago’s Culinary History.

Top: Exterior of the Kungsholm at 100 East Ontario Street, Chicago, July 15, 1954. CHM, ICHi-052263; J. Johnson Jr., photographer. A man touches up puppets at the Kungsholm, Chicago, September 8, 1968. ST-70006535-0037, Chicago Sun-Times Collection, CHM. Bottom: Kungsholm luncheon menu, July 2, 1952. CHM, ICHi-085972-001, ICHi-085972-002, ICHi-085972-003.

Google Arts & Culture

Google Arts & Culture is an online platform that puts the treasures, stories, and knowledge of more than 2,000 cultural institutions from eighty countries at your fingertips. The Chicago History Museum’s portal includes stories from throughout the city’s history. Peruse the designs of Chicago-born couturier Mainbocher, learn about the work of civil rights leader Reverend J. H. Jackson, and so much more! See All Exhibits

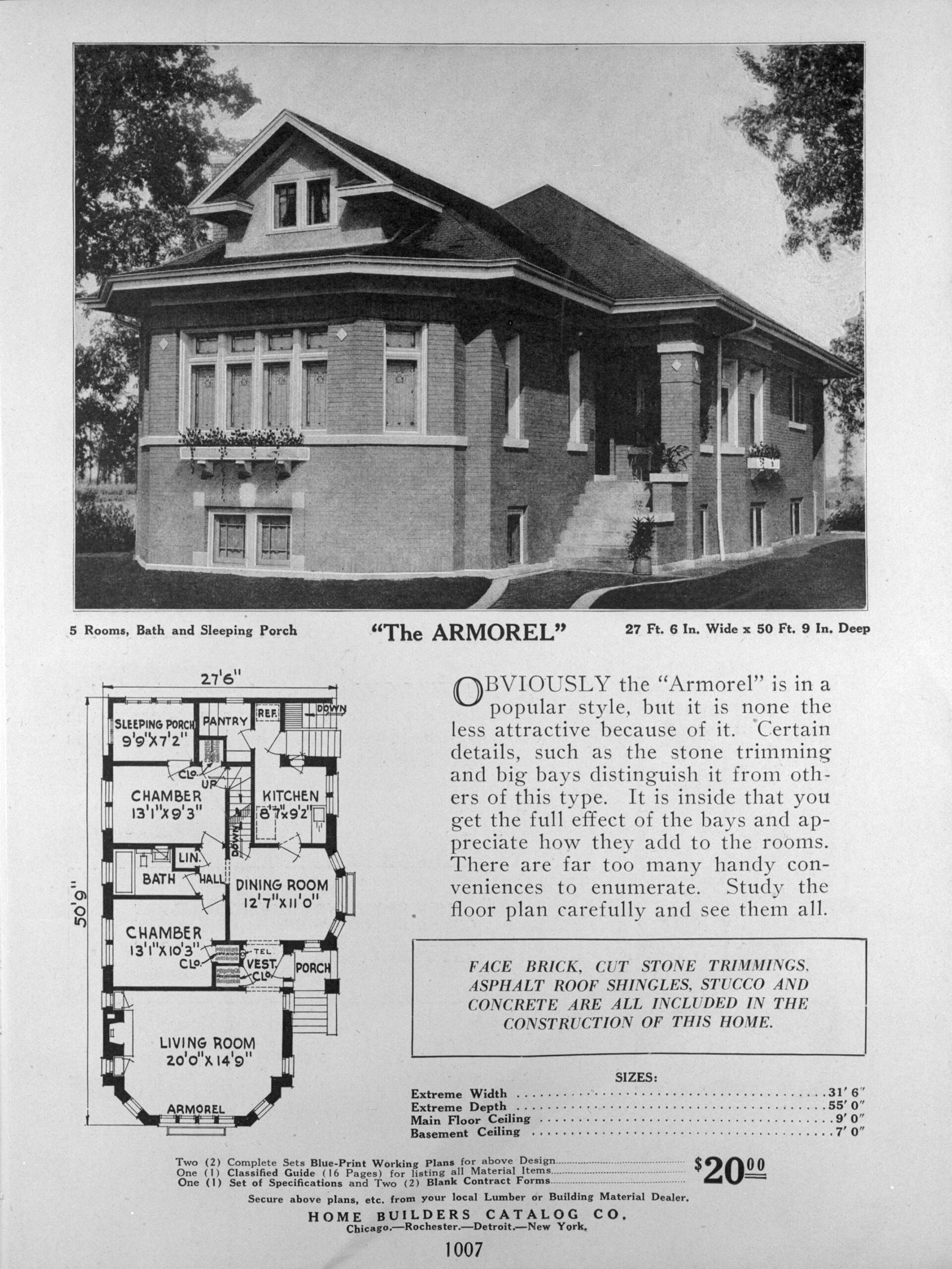

An image, floor plan, and text for The Armorel, a bungalow from the Home Builders Catalog, 1926. CHM, ICHi-015886

About one hundred years ago, Chicago saw a building boom of single-family homes of a certain style—the bungalow. The word “bungalow” derives from the British colonial experience in India, and beginning in the twentieth century, architects, builders, and developers adopted the term to describe modern houses built throughout the United States.

In Chicago, a few architects had begun to design and build expensive, Craftsman-style, California-influenced bungalows in affluent locations of the city by 1910. When the housing market boomed in the 1920s, developers throughout the metropolitan region marketed lower-priced “bungalows” to an expanding range of middle-class families. These structures all had modern plumbing, electricity, and central heating. Within the city limits, a common form of bungalow was a rectangular brick structure with a modestly pitched, hip-raftered roof and a small distinctive front porch. It fit on narrow city lots and followed the floor plan of earlier one-story working-class houses.

However, builders constructed a great variety of structures even in the city’s “bungalow belt”—houses that were built in the 1910s and 1920s in a collar just inside and around the city limits. By 1930, one-fourth of all residential structures in metropolitan Chicago were less than ten years old, many of them bungalows, ranging in cost from about $2,500 to $10,000 (about $38,000 to $155,000 in 2020).

A form of bungalow continued to be built in working-class areas of the South Side in the 1960s. However, the bungalow lost popularity among house buyers after World War II, as ranches and split-levels became the dominant house style in new areas. In the early twenty-first century, “historic” bungalows resurged as popular housing in gentrifying areas of the city. In response to that renewed interest, the municipal government started the Chicago Bungalow Association in 2000, which helps homeowners maintain, preserve, and adapt their bungalows. Learn more about bungalows in Chicago in the Encyclopedia of Chicago.

Digital Chicago

Shortly after World War II, the Chicago Tribune sponsored a contest for residential design—the Chicagoland Prize Homes Competition. Several of the competition’s twenty-four winning designs were executed in the Chicagoland area, some of which are still standing. In the Digital Chicago project Chicagoland Prize Homes, researchers plotted the homes’ locations and included images of the homes as they currently exist, showing the ways in which Americans’ ideas about housing have changed since the mid-twentieth century. View the Project

PRIMARY SOURCE TYPE: PHOTOGRAPHS, ORAL HISTORIES

Many people see Chicago as the American Medina, drawing Muslims from all over the country and world as Medina, Saudi Arabia has done for centuries. Beginning with the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, which featured some of the first mosques in the United States, Chicago is now home to a diverse Muslim community: followers from the US and abroad; members of various sects; and converts and those who were raised in the faith.

The American Medina: Stories of Muslim Chicago exhibition offered teachers and students an opportunity to learn about Muslim communities in Chicago. The exhibition drew from more than 100 interviews conducted with Muslim Chicagoans sharing their stories of faith, identity, and personal journeys. Dozens of objects from local individuals and organizations, such as garments, artwork, and photographs, as well as videos and interactive experiences expand on how and why Chicago is known as the American Medina.

Download the American Medina Educator Learning Guide.

“Many people do not see a connection between science and dance, but I consider them both to be expressions of the boundless creativity that people have to share with one another.”

In 1992, when Dr. Mae Jemison became the first Black woman to travel into space, she fulfilled one childhood dream while highlighting another interest—dance. Both of these lifelong passions began while growing up in Chicago.

Dr. Mae Jemison dances with the Morgan Park High School pom-pom team, Chicago, October 15, 1992. Photograph by John H. White for the Chicago Sun-Times ST-17500823, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Mae Jemison was born in Decatur, Alabama, on October 17, 1956. The youngest of three children, she was three years old when her family moved to Chicago, first living in Woodlawn and eventually settling in Morgan Park. Her father, Charlie, worked as a maintenance supervisor for a charity organization, as well as a roofer and carpenter, and her mother, Dorothy, taught English and math at Ludwig Van Beethoven Elementary School in Bronzeville.

As a young girl, Jemison showed an interest in science and enjoyed reading science fiction and books about astronomy. The televised Apollo and Gemini space flights during the late 1960s and early 1970s further inspired her to pursue a path in the STEM fields. Jemison also began taking dance lessons at age nine and was involved in dance and theater productions. She considered becoming a professional dancer, but her mother advised her to do so after college, saying “You can always dance if you’re a doctor, but you can’t doctor if you’re a dancer.”

A stellar student, Jemison graduated from Morgan Park High School at age sixteen and attended Stanford University on a scholarship. There, she majored in chemical engineering and African and Afro-American Studies, graduating in 1977. Jemison then moved to New York City to earn her MD at what is now Weill Cornell Graduate School of Medical Sciences. Being in New York gave her the opportunity to take lessons at the Ailey School, which is affiliated with the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater (AAADT). Founded in 1958 by dancer and choreographer Alvin Ailey, the visionary modern dance company is often regarded as the foremost dance interpreter of the African American experience.

Jemison graduated from medical school in 1981 and then served in the Peace Corps in Sierra Leone and Liberia. Upon returning to the US in 1985, she entered private practice in Los Angeles and began attending graduate engineering courses. After seeing the 1983 flights of Guion Bluford and Sally Ride, the first African American in space and the first American woman in space, respectively, Jemison felt empowered to apply to NASA’s astronaut training program. She was accepted in 1987 and was selected to serve as a mission specialist aboard the Space Shuttle Endeavour in 1992.

Prior to the flight, Jemison wrote to Judith Jamison, a renowned dancer and then-AAADT director, asking to bring Jamison’s costume for Cry up to space with her. While the costume was unavailable, AAADT sent her a book about Alvin Ailey and a poster autographed by Jamison, which orbited the Earth with Jemison during September 12–20. The above photograph shows Dr. Jemison during a visit to her alma mater Morgan Park High School in Chicago after her historic flight. You can see it and many other Chicago Sun-Times images now available at CHM Images.

On this day in 1871, a fire began on DeKoven Street in a barn owned by Catherine and Patrick O’Leary. Fueled by a gale-force wind, this blaze grew into the Great Chicago Fire. Advancing northward over three days, the inferno destroyed three and a half square miles in the heart of the city, leveling more than 18,000 structures. One-third of the city’s 300,000 residents lost their homes, and at least 300 perished. As devastating as it was, the disaster provided the young city with new opportunities and a chance for renewal.

Chicago rebuilt so quickly that within four years, there were no traces of the fire to be seen. Due to insurance companies and city governments mandating fire-resistant construction, architects began experimenting with steel, and by 1885, the Home Insurance Building, the world’s first modern skyscraper, was completed. By 1890, Chicago’s population tripled to one million and was selected by the US House of Representatives to host the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition.

So, how have catastrophes shaped and even improved modern city life? For the October 2020 issue of The Atlantic, CHM assistant curator Julius L. Jones spoke to Derek Thompson about the Great Chicago Fire within the content of how calamities can force us to question the physical and societal structures around us, break down the political and regulatory barriers to progress, and attract the funding and talent that can solve big problems and spur technological leaps. Read the article.

The Chicago skyline you see today was largely influenced by Bruce Graham, a Peruvian American architect who was born in Colombia and raised in Puerto Rico. Bruce Graham worked at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill from 1951 to 1989, where his projects included the Inland Steel Building (1957), John Hancock Center (1969), and Sears Tower (1974), among others.

An undated portrait of Bruce Graham from Wikimedia Commons.

Graham’s father, Carroll, was born in Canada, raised in Puerto Rico, and traveled throughout Latin America for his work as a bank inspector for Chase Bank. While in Arequipa, Peru, he met and married Angélica Gómez de la Torre Bueno, and was transferred to La Cumbre, Colombia, where Bruce John Graham was born on December 1, 1925. Within a few months, the family moved to San Juan, Puerto Rico, where Graham grew up, not speaking English until age seven or eight.

He showed interest in drawing as a youth, taking drawing lessons and sketching cartoons. Graham was also fascinated by San Juan’s built environment, so he combined those interests and made a hobby of mapping the city’s slum neighborhoods. After attending Colegio San José Río Piedras for high school, he graduated at age 15 and came to the United States to study at the University of Dayton on a scholarship, but his studies were interrupted by World War II.

Graham served in the US Navy from 1941 to 1945 and resumed his education at the University of Pennsylvania on the GI Bill, graduating in 1948. From then on, he grew his career in Chicago, first at Holabird, Root, and Burgee until 1951, then at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill until 1989.

The Inland Steel building at 30 West Monroe Street, Chicago, March 24, 1958. HB-21235-B4, CHM, Hedrich Blessing Collection.

As Graham reached the heights of his storied career, he maintained ties to South America as one of the founding members of the School of Architecture at the Universidad de los Andes in Bogotá, Colombia, and as an honorary member of the Institute for Urbanism and Planning at the Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos in Lima, Perú, the oldest continuously operating university in the Americas.

The Sears Tower under construction, Chicago, c. 1972. In the left background is the John Hancock Center. HB-36150-H2, CHM, Hedrich-Blessing Collection.

Learn more about Bruce Graham’s extraordinary life and career in our Chicago History article, “Creating a Dance: Interviews with Bruce Graham and Maria Tallchief.”

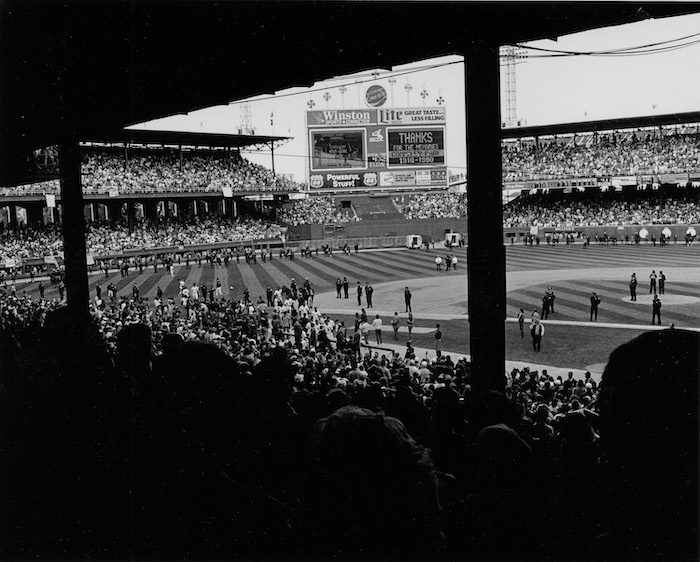

On September 30, 1990, the Chicago White Sox played their final game at Comiskey Park.

Police guarding the field at the final game at Comiskey Park, Chicago, September 30, 1990. CHM, ICHi-052133; Melody Miller, photographer

Designed by Zachary Taylor Davis, the fireproof steel and concrete stadium, which replaced the all-wooden South Side Park, was located at 35th Street and Shields Avenue and built on a former city landfill. The stadium was originally named White Sox Park but was renamed a few years later after White Sox owner Charles Comiskey. The park was known for being pitcher-friendly, thanks to design input from hall of famer Ed Walsh, with dimensions of 362 feet down the right and left field lines and 440 feet to deep center field. In its eighty years, not a single player hit 100 career home runs there. Carlton Fisk holds the record with ninety-four.

Comiskey Park during construction, 1910. SDN-008841, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

Comiskey Park hosted more than 6,000 Major League games and four World Series, including the 1918 World Series between the Chicago Cubs and Boston Red Sox (because its seating capacity was larger than that of Wrigley Field, then known as Weeghman Park). It was the site of the first Major League Baseball All-Star Game in 1933 in conjunction with the A Century of Progress International Exposition. During that game, Babe Ruth hit the first ever MLB All-Star home run. The park also hosted many of the East-West Negro League All-Star games from 1933 to 1962.

Comiskey Park during a game, c. 1910. CHM, ICHi-019088; Barnes-Crosby Company, photographer

In addition to the White Sox, the Negro American League’s Chicago American Giants played home games there from 1941 through 1950. The NFL’s Chicago Cardinals and two North American Soccer League teams (the Mustangs and the Sting) also called Comiskey home. The stadium also served as a concert venue, hosting musical acts including The Beatles, AC/DC, and The Jacksons.

The venue underwent numerous numerous cosmetic and seating capacity changes over the years, including the famous “exploding” scoreboard, installed in 1960 by then-owner Bill Veeck. The 130-foot scoreboard included lights, sirens, a message board, and the iconic pinwheels. The sound effects, strobe lights, and fireworks went into action whenever a White Sox player hit a home run. By 1971, Comiskey Park was the oldest park still in use in the Major Leagues.

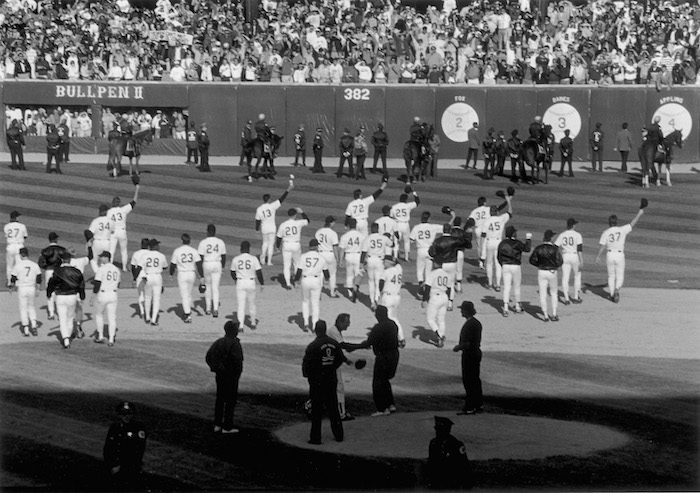

On September 30, 1990, a crowd of 42,849 attended the ballpark’s final game—a 2–1 Sox victory over the Seattle Mariners. Charles Comiskey, former White Sox vice president and grandson of the park’s namesake, was in attendance. Former All-Star left fielder Minnie Miñoso brought the lineup card to the umpires before the game, and at the end organist Nancy Faust played a final rendition of “Na Na Hey Hey Kiss Him Goodbye.”

The Chicago White Sox baseball team waves farewell to fans after the final game at old Comiskey Park, Chicago, September 30, 1990. CHM, ICHi-035694; Melody Miller, photographer

A new park, now named Guaranteed Rate Field, was constructed directly across 35th Street, and Comiskey Park was demolished in 1991 and turned into a parking lot to serve the new park. The existence of Old Comiskey is remembered with its field and foul lines painted on the lot and a marble plaque where home plate was once located.

Additional Resources

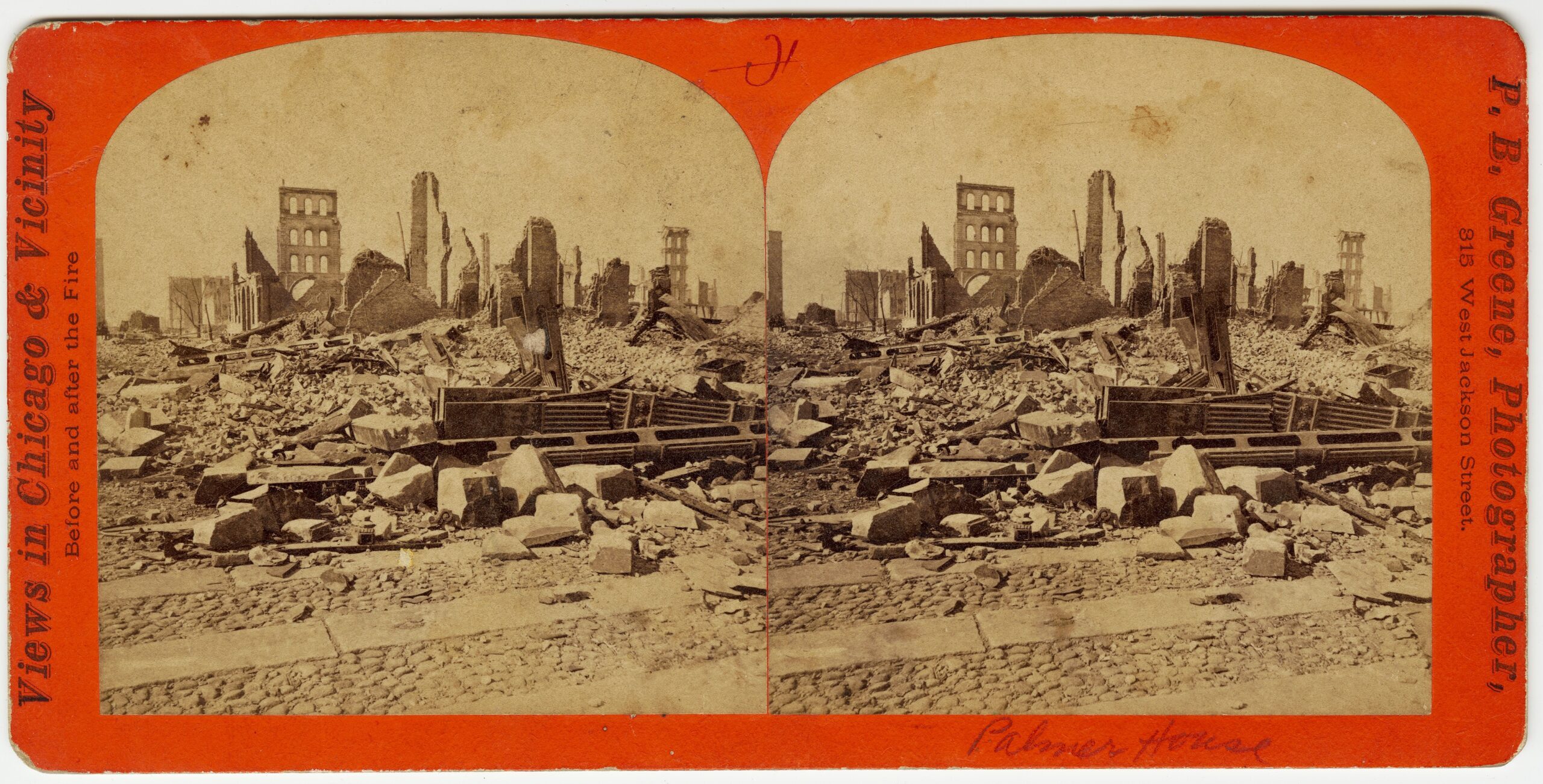

In light of the recent news that the Palmer House Hotel faces a $338 million foreclosure suit, CHM staff members take a look back at its three iterations.

The Palmer House Hotel was long the pinnacle of grandeur and luxury in Chicago and was for decades the hotel of choice for visiting presidents, dignitaries, and businesspeople. The crown jewel in the holdings of department store mogul turned real-estate developer Potter Palmer, it was a wedding present to his wife, Bertha.

The First Palmer House (1870)

On September 26, 1870, the first Palmer House opened for business at State and Quincy Streets. With 225 rooms, its furnishings alone cost $100,000, or half the construction cost. An additional Palmer House was under construction nearby, but both structures were destroyed by the Great Chicago Fire on October 8, 1871.

A stereograph of the Palmer House ruins after the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. CHM, ICHi-026749; P. B. Greene, photographer

The Second Palmer House (1873–1923)

Palmer quickly rebuilt on the same site, employing calcium lights so workers could press on through the night. The resulting seven-story, $13 million hotel designed by architect John M. Van Osdel opened on November 8, 1873, marking the start of what became known as the nation’s longest continually operating hotel.

An engraving entitled “Working at Night on Palmer’s Grand Hotel, by Calcium Light,” 1871. CHM, ICHi-002930

The hotel was filled with Italian marble and rare mosaics and was so ornate that it was alternately mocked and praised. Like many Chicago buildings in the late nineteenth century, the Palmer House claimed to be fireproof.

An albumen print of the second Palmer House Hotel, Chicago, c. 1885. CHM, ICHi-069676; J. W. Taylor, photographer

The Palmer House not only served transient visitors but also appealed to wealthy permanent residents who found in the palace hotel a convenient way to set up trouble-free, elegant households.

The ladies’ entrance to the Palmer House hotel, which can be seen in the lower left corner of the albumen print, Chicago, September 19, 1903. DN-0001231, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

This ornate headboard (1873) on the right was part of a bridal suite in the second Palmer House. Made of ebonized and gilded black walnut in a Renaissance style, the headboard was surmounted by a French-style canopy. It was made by W. W. Strong Furniture Co., Chicago’s premier furniture dealer and manufacturer of the 1870s. You can find it on display in Chicago: Crossroads of America.

The Third Palmer House (1925–present)

The economic boom and population growth of the 1920s and Chicago’s increasing attractiveness as a convention city led to a perceived shortfall in hotel rooms. Thus, the Palmer Estate decided to raze the Palmer House for a new $20 million rendition on the same site. Designed by the firm Holabird & Roche and built during 1923–25, its twenty-five stories housed 2,268 rooms and for a very short time held the record as the world’s largest hotel.

The current Palmer House hotel under construction, 17 East Monroe Street, Chicago, c. 1925. HB-05894-M, CHM, Hedrich-Blessing Collection

As with many luxury hotels, the Palmer House boasted a grand lobby, monumental staircases, bridal suites, dining rooms, ballrooms, a bar, and a barbershop.

The barbershop at the Palmer House Hotel, Chicago, c. 1930. CHM, ICHi-080559; Raymond W. Trowbridge, photographer

An eager crowd at the Palmer House Bar waits to be served upon the repeal of Prohibition, Chicago, 1934. DN-A-4938, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

In 1933, Palmer House converted its Empire Dining Room into an entertainment venue and supper club. Before air travel was common, Chicago was a popular stopping point for celebrities traveling by train between New York and Los Angeles, and the Palmer House saw its share of big-name entertainers, including Frank Sinatra, Judy Garland, Ella Fitzgerald, Harry Belafonte, Louis Armstrong, and Liberace.

The Empire Room at the Palmer House Hotel, Chicago, c. June 4–8, 1936. HB-03386-C, CHM, Hedrich-Blessing Collection

While its hotel rooms are standard upscale fare, the Palmer House’s palatial lobby, conceived as a European drawing room, remains one of the most magnificent in the world.

View of the Great Hall Lobby from the Empire Room at the Palmer House, Chicago, 1925. CHM, ICHi-038783

An undated postcard of the third Palmer House Hotel, Chicago. CHM, ICHi-069672

Eclipsed in the 1980s by posh hotels on North Michigan Avenue closer to fine shopping, the Palmer House—a part of the Hilton Hotel chain since 1945—continued to attract guests because of its proximity to the Loop business district, the Art Institute of Chicago, and downtown theaters.