Forty years ago today, a series of grim deaths in the Chicago metropolitan area gripped the nation, changing how American consumers buy over-the-counter medicine and the way public health officials respond to crisis situations.

The Chicago Tylenol murders, as they’ve come to be known, began in the morning hours of September 28, 1982, with a 12-year-old Elk Grove Village resident named Mary Kellerman, who was given a Tylenol tablet by her parents in response to complaints of a sore throat. No one could have imagined that within a few hours, Mary would be dead, due to the medication being tainted with a lethal substance. Later that same day, Adam Janus, a postal worker in Arlington Heights, died after taking similarly doctored Tylenol. In a grim twist of fate, his brother and sister-in-law would die after ingesting the same tainted medication they found in Adam’s home. They were there to support and share company with family members after hearing about Adam’s passing. Following these deaths, three more casualties (a total of seven) linked to tainted medicine were reported, two in the suburbs and one in Chicago.

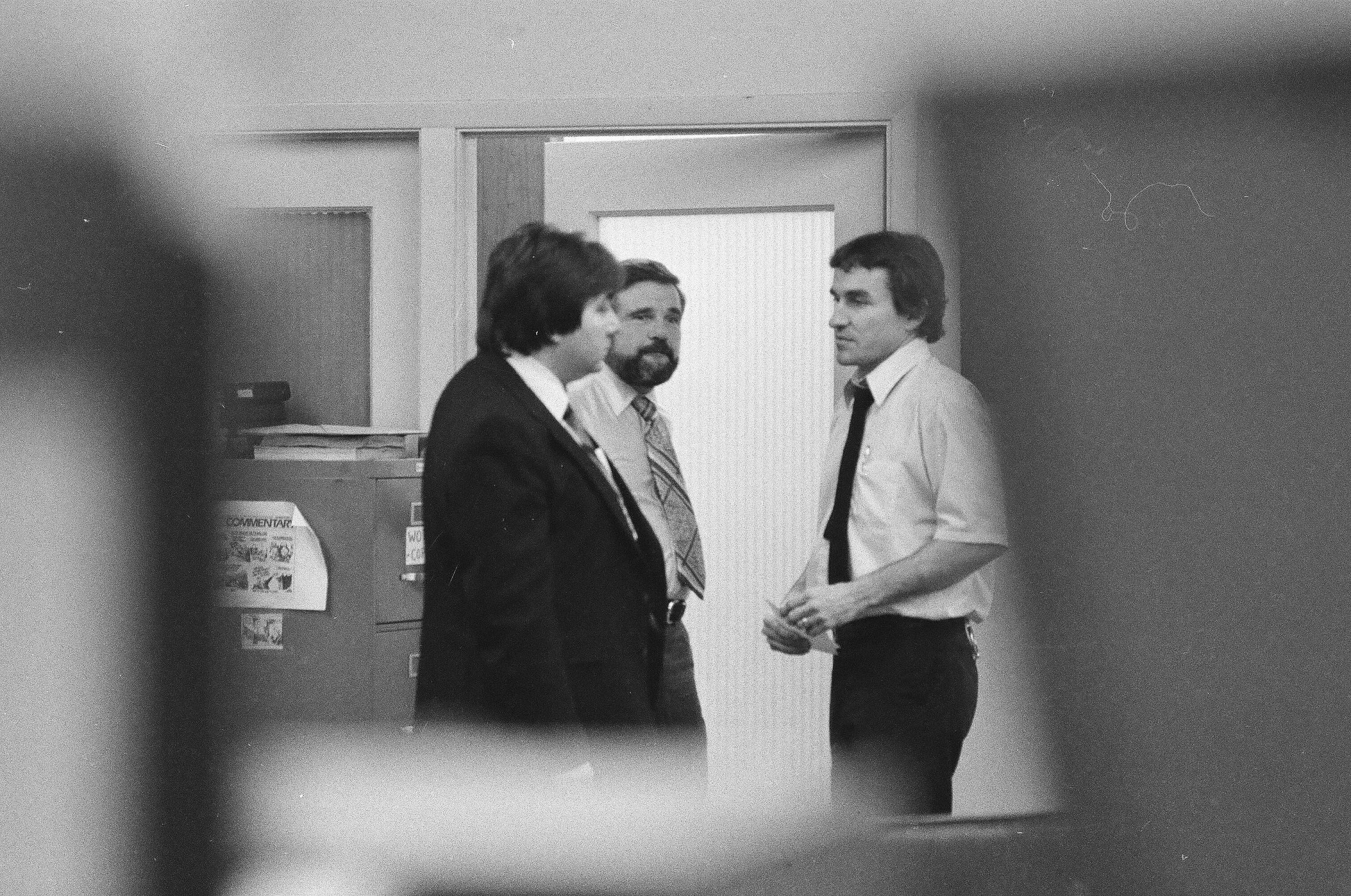

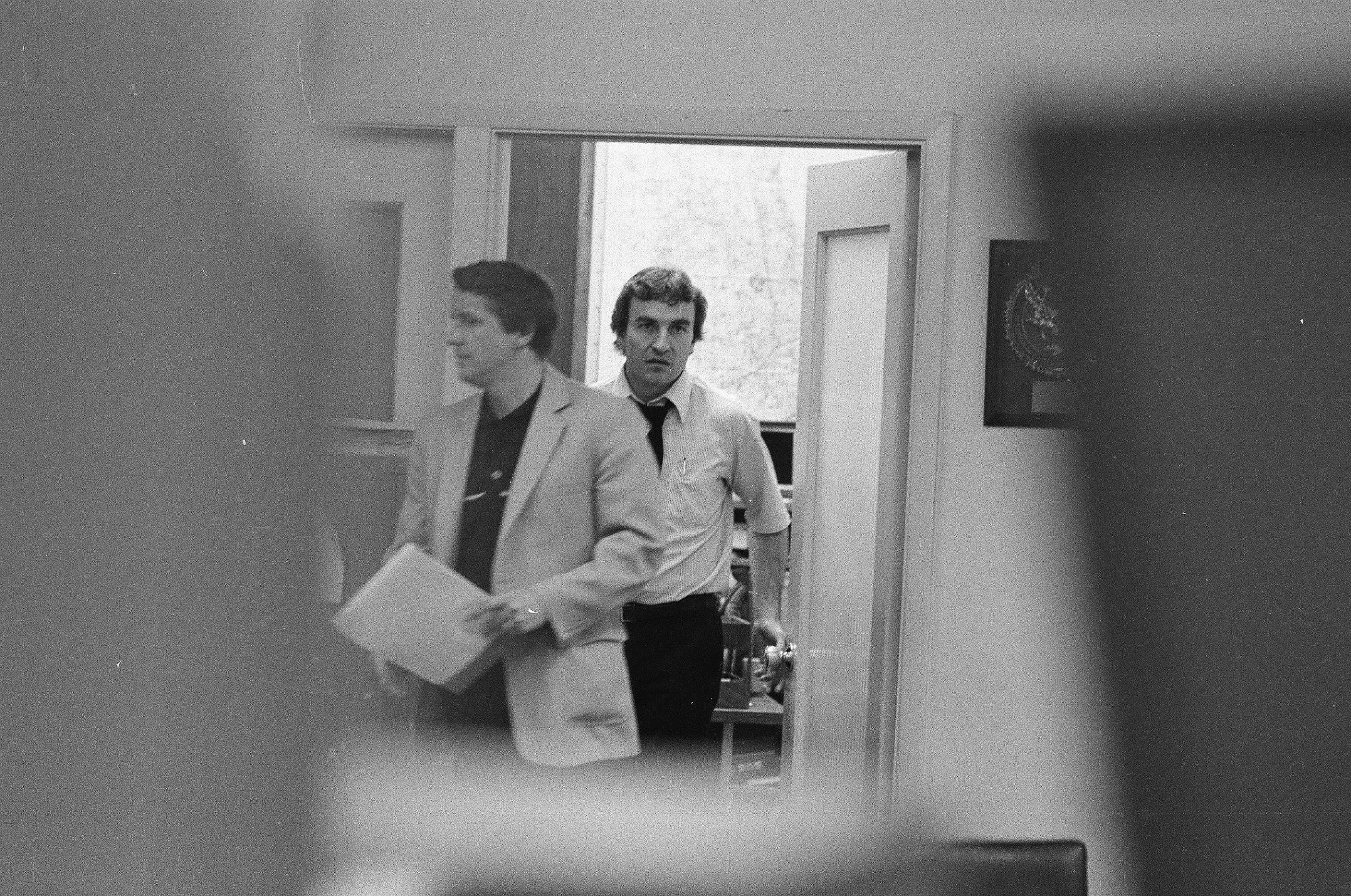

Investigators at the Attorney General North West Criminal Investigation Center at River Road and Rand Road, Des Plaines, Illinois. December 2, 1982. ST-20001914-0009, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM; photograph by Gene Pesek

The mysterious deaths immediately raised red flags for local officials and health care providers who responded to help with the investigation, given the peculiar nature of the casualties and the alarming rate at which they were spreading. It became apparent that as much as this was a broad-ranging murder investigation, it would also be a public health crisis. It was quickly established that the link among all the victims was consumption of Tylenol tablets shortly before death, and authorities sent off medication bottles found in homes of the deceased for testing. When the test results came back, it was found that the acetaminophen pills in these containers had been swapped with tablets containing lethal doses of potassium cyanide.

Investigators at the Attorney General North West Criminal Investigation Center at River Road and Rand Road, Des Plaines, Illinois. December 2, 1982. ST-20001914-0009, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM; photograph by Gene Pesek

Within 48 hours, Mayor Jane Byrne, with the cooperation of local law enforcement, health officials, and universities, had all Tylenol products pulled from local grocers and pharmacies and shipped off to various laboratories in the area for integrity testing. Area residents were instructed to dispose of any Tylenol products they had at home, and the drug manufacturer issued a nationwide recall. This mass panic caused a considerable amount of chaos in the area and across the nation, with many towns going as far as canceling Halloween trick-or-treating for fears of candy tainted in the same way as the medication falling into the hands of children.

To this day, the perpetrator of the murders has not been identified or apprehended by authorities. A man from New York, James Lewis, claimed responsibility for the events and demanded $1 million dollars from Tylenol’s parent company in exchange for stopping the killings. However, it was quickly established that he could not have been the person responsible, and he served 13 years in prison for extortion.

Beyond being a grim part of the city’s history, this incident had a profound impact on the US drug industry. In 1983, Congress passed the “Tylenol Bill,” which made it a felony to tamper with consumer products. In 1989, the FDA updated their policies to make medications more tamperproof, requiring tamper-evident seals on all over-the-counter medications and the eventual transition in manufacturing to more modern “caplets” that are harder to tamper with than older medications.