CHM curator of religion and community history Rebekah Coffman writes about CHM’s collection of souvenirs contemporary to the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition and how they inform the stories we tell today.

Souvenir pins from the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893. CHM, ICHi-066817. Souvenir silver spoons featuring the likeness of Bertha Honoré Palmer from the World’s Columbian Exposition, 1893. CHM, ICHi-053270.

The word “souvenir” is the French verb “to remember,” and by extension, souvenirs as objects are meant to embody people’s experiences, stories, and memories. In the Chicago History Museum’s collection of 23 million objects, a robust number of items are related to Chicago’s two world’s fairs: the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition (WCE) and 1933–34 A Century of Progress International Exposition. Items typically classified as “souvenirs” of the fair–such as postcards, photographs, spoons, pins, and ribbons–are so well represented in CHM’s holdings, we no longer accept donations of most WCE ephemera.

The questions we face now encompass the context of all these souvenirs, such as:

- For whom were they made, what do they represent, and what memories or remembrances are they meant to ignite?

- Can we use them to tell a fuller story beyond the personal memories they were intended to evoke?

- What are the deeper, harder histories that were not previously centered in their interpretation or in other recollections and retellings of the fairs?

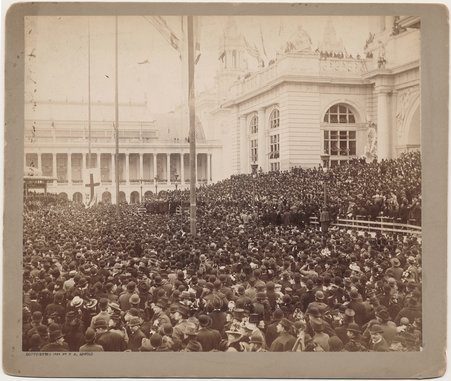

Opening day of the World’s Columbian Exposition, May 1, 1893. CHM, ICHi-059979.

Open from May 1 through October 30, the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition brought more than 27 million visitors to Chicago. Souvenirs such as those above were made and bought as personal keepsakes at a never-before-seen scale. Souvenir manufacturing and purchasing exploded in the nineteenth century as industrial advancements allowed for mass production. Items such as collectable spoons had gained popularity with wealthy and upper middle-class Europeans and Americans on grand tours in the mid-nineteenth century. By the 1890s, as they became more accessible and affordable, a broader audience had financial access to commemorative items. Beyond just physical tokens, souvenirs served as an access point to a marking of social class previously reserved for the wealthy. They also held individual symbolic meaning and memory for their purchasers, resulting in their abundant presence today.

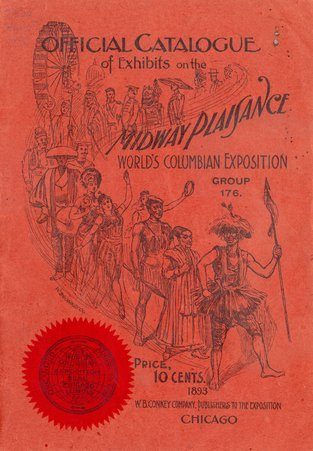

Cover of the Official Catalogue of Exhibits on the Midway Plaisance, 1893. CHM, ICHi-065727.

In the case of the WCE, they also form an important part of our historical memory and speak to the process of building a collection to represent a city’s history drawing on a very nineteenth-century colonial notion of collecting not just objects, ideas, and memories but identities and people.

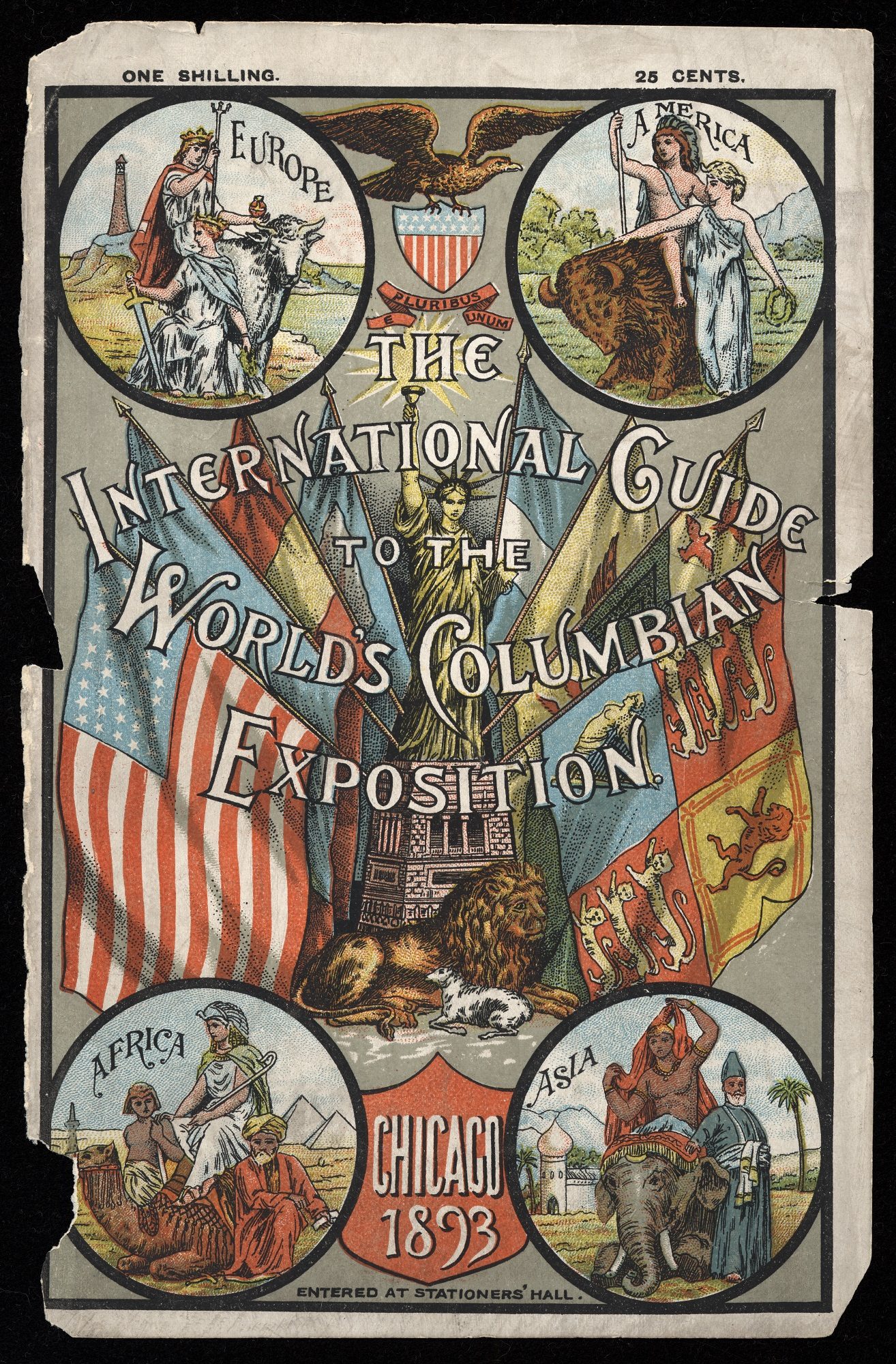

Front cover of The International Guide to the World’s Columbian Exposition, published by the International Guide Syndicate, 1892. CHM, ICHi-040435

World’s fairs―broadly speaking―created the canvas upon which participating nations could project a filtered, essentialized view of themselves (and others) on a global platform. The 1851 Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations in London set the tone for Victorian-era framing of an empire on display. This model proved useful to both the continuation of global exhibitions but also the development of fields of study such as anthropology and museology. The process of classifying and showcasing identities through a colonial lens has translated into the complex legacy many museums face. Collections, including those surrounding world’s fairs, center privileged experiences with many voices and experiences represented through racialized prejudice as a view of the “other” and lack equitable representation of diverse perspectives.

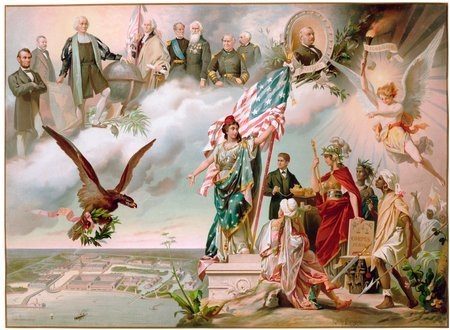

Allegorical lithograph of Christopher Columbus with US presidents and the 1893 WCE by Rodolfo Morgari, CHM, ICHi-025233

The WCE aimed to position Chicago as a sophisticated global center and shift away from its reputation as an industrially polluted, dangerous city at the edge of the western frontier. Many US cities experienced a sense of fragmentation after the Civil War, compounded by massive industrial growth, class divides, and racial tensions. In Chicago, these pressures were amalgamated in the wake of the Great Fire of 1871, and it looked to rebrand itself as a city of future promise. This opportunity came with the successful advocacy to host the 1893 world’s fair commemorating the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s arrival in North America. This positioning asserted racial and intellectual dominance of Euro-Americans over Indigenous peoples as manifested through an idealized narrative of Columbus’s role in establishing a religiously motivated presence in the future United States of America.

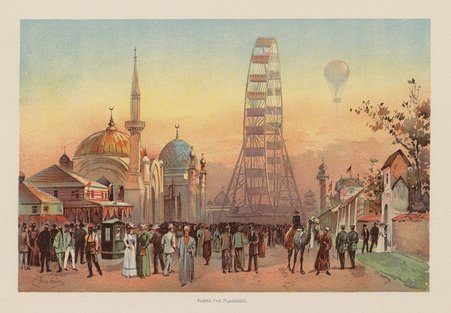

Color illustration by Charles Graham titled “Along the Plaisance,” World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893. CHM, ICHi-052343.

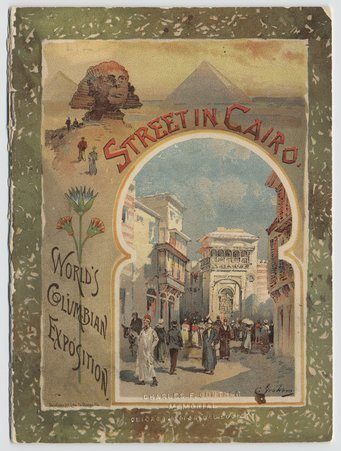

The construction of the WCE was a reaction to and an embodiment of this cultural supremacy through its construction as a duality of identity between the White City, which symbolized a utopian vision of the United States’ future, and the Midway Plaisance, which represented anthropological foundations. Western perspectives of a certain global racial stratification informed divisions between exhibitors, with selected nations submitting plans for national pavilions while others were relegated to the more carnivalesque atmosphere of the Midway—and some notably without representation at all. Ethnological displays romanticized, exoticized, primitivized, and objectified those who represented the living embodiment of their cultural identity for the enthusiastic, and at times cruel, audience.

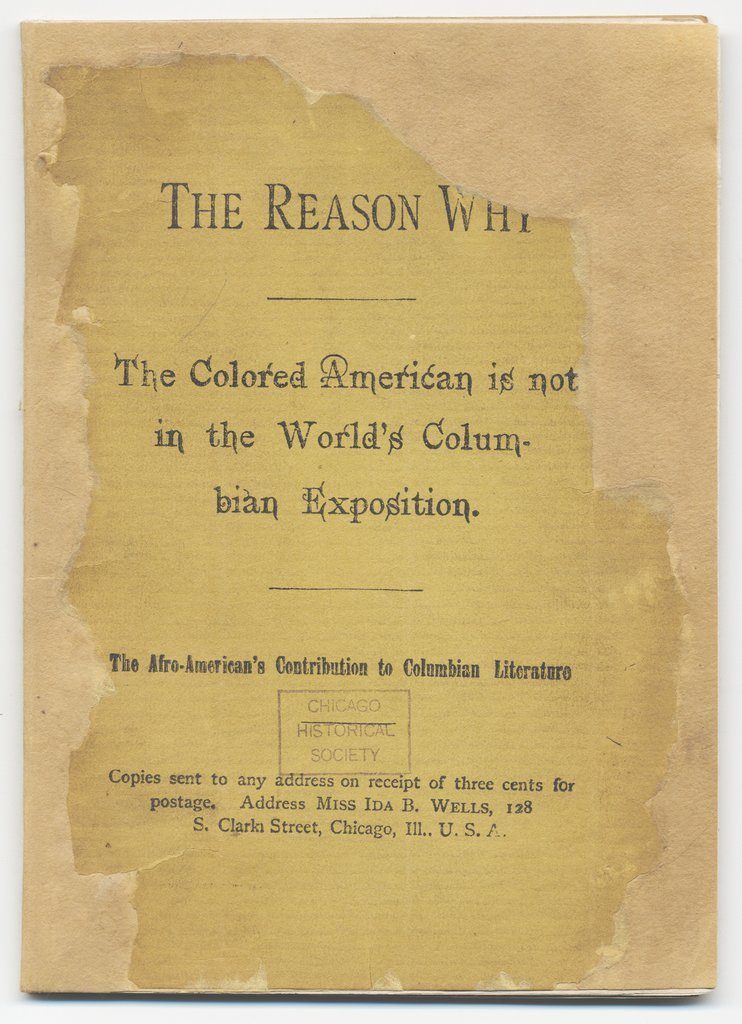

Front cover of The Reason Why the Colored American is not in the World’s Columbian Exposition by Ida B. Wells, 1893. CHM, ICHi-040399.

This division did not go without commentary at the time. Powerful examples of dissenting voices and personal advocacy persist, though captured in less represented ephemera. For example, Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Frederick Douglass published a pamphlet protesting the lack of African American representation, with Wells referring to the White City as the “white sepulcher.” Simon Pokagon gave a cutting critique of Indigenous displacement through his speech, and later publication, for Chicago Day at the fair, questioning why they would “. . . celebrate our own funeral, the discovery of America.” These are just two examples of the wide gap of experiences of the fair based on race and point to the possibilities of further counternarratives yet to be unearthed.

Cover of pamphlet titled “Street in Cairo,” 1893, CHM, ICHi-038001_a. Group of men near the Turkish village at the Midway Plaisance, 1893. CHM, ICHi-025117.

These collections and interpretations around the WCE bridge larger questions of how we address representational disparities in a broader way. The significance of our collections is not just in the number of items held but the stories they tell. An overabundance that represents a particular lens of the WCE warrants an important rebalancing in the items we collect, the space we make, and the perspectives we share in addressing the legacy of the WCE and how it has shaped Chicago—and global—history.

Additional Resources

- Listen to historian Robert Rydell discuss his book All the World’s a Fair: Visions of Empire at American International Expositions, 1876-1916 with Studs Terkel

- Read the Encyclopedia of Chicago overview entry on the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 and entry on World’s Columbian Exposition

- Learn more about CHM’s collecting scope

- Read the Encyclopedia of Chicago entry about Ida B. Wells-Barnett at the 1893 world’s fair