To mark what would have been the 108th birthday of Studs Terkel, Peter T. Alter, CHM chief historian and director of the Studs Terkel Center for Oral History, reflects on the memorable moments he shared with Studs at the Museum and Studs’s enduring cultural influence.

When I started working at the Chicago History Museum in 1999 as a public historian, I knew very little about oral history and museums. I did, however, know who renowned author, actor, journalist, oral historian, disc jockey, and television personality Studs Terkel was. The first Studs book I ever bought was “The Good War”: An Oral History of World War II (1984).

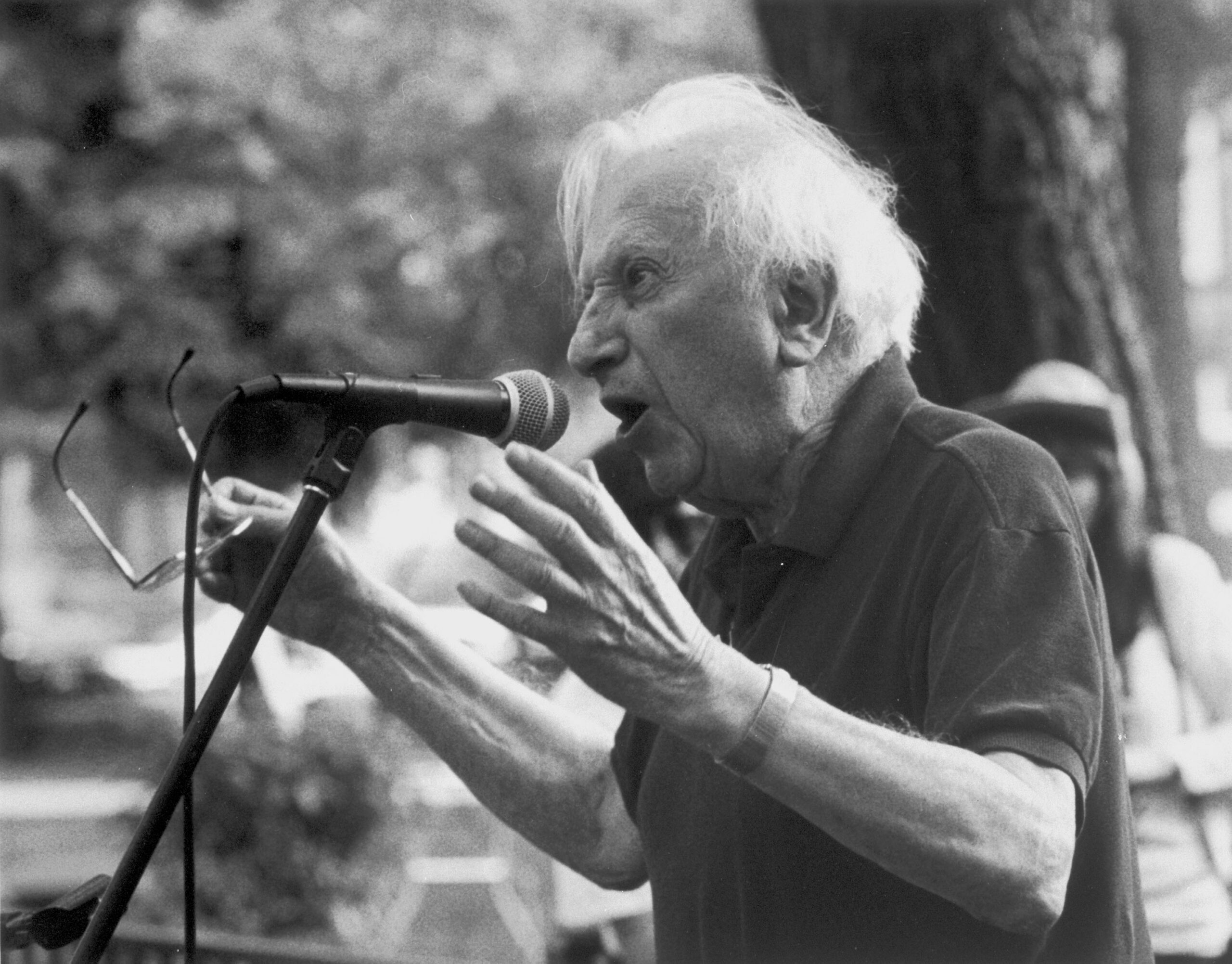

In the 1980s, one of my first trips with my newly minted driver’s license was to buy this Pulitzer prize-winning book at a local bookstore in western Illinois where I grew up. A few years later, I saw Studs speak at the Bughouse Square Debates, a celebration of free speech at Washington Square Park on the North Side.

Studs Terkel making a speech in a park, Chicago, c. 1995. CHM, ICHi-034937

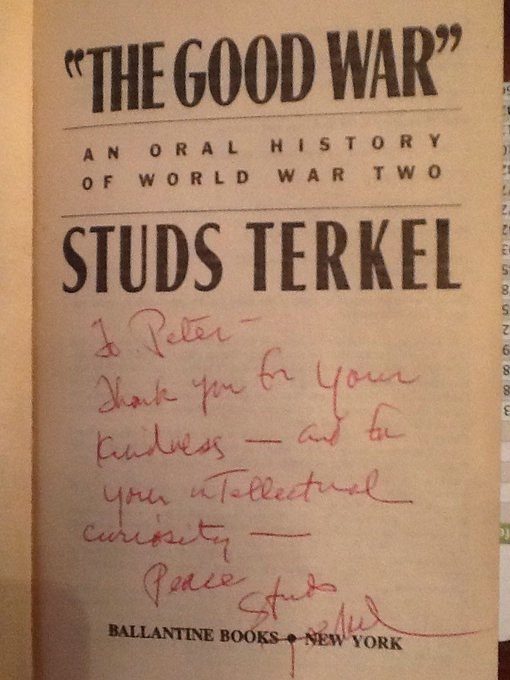

Jumping ahead to my first months at the Museum, I got to know Sylvia Landsman, my department’s volunteer. By that time, Studs was the Museum’s distinguished scholar-in-residence, a position he held from 1997 to about 2005. Sylvia met and became friends with Studs at CHM, and they bonded over the fact that they both attended the University of Chicago in the 1930s. In fact, he thanks her in his book Hope Dies Last: Keeping the Faith in Troubled Times (2004). Sylvia helped Studs mail packages and with other tasks. One day Sylvia wasn’t available, and I stood in for her when he needed help sending a book. For that simple assistance, he signed my copy of the “The Good War.”

Studs’s message reads: “To Peter—Thank you for your kindness—and for your intellectual curiosity—Peace, Studs Terkel.”

Over the following years, I continued to be an eyewitness to Studs. I briefly met Mamie Till Mobley, Emmett Till’s mother, when Studs interviewed her at the Museum. Fourteen-year-old Emmett, a native Chicagoan, was lynched in Mississippi in 1955. I also saw Studs work with the young people of the Museum’s award-winning Teen Chicago project as they developed their own oral history initiative.

CHM’s Teen Council in 2004 with Studs (seated, center) wearing his trademark red socks.

Later, I started to listen to some of the digitized versions of his interviews. I quickly determined that my favorite one was his 1964 interview of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. while the two of them sat at the “bedside” of Grammy award-winning gospel singer Mahalia Jackson at her South Side home. When I listen to Dr. King talk with Studs, I can imagine him with his ubiquitous open-reel recorder.

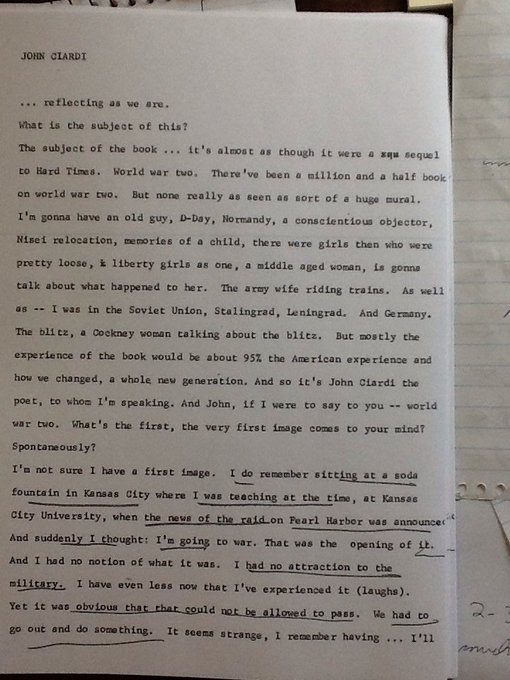

For five years, I worked as the Museum’s archivist in charge of its wonderful archival and manuscript collections, including Studs’s papers. When digging through his files, I found the transcript for his interview of Joe Ciardi, a well-known poet, whom Studs interviewed for “The Good War.” In the transcript, Studs explains the connection between that book and a previous book, Hard Times: An Oral History of the Great Depression (1970). While I was archivist, the Museum acquired the papers of Eliot Asinof, the author of the book Eight Men Out (1963), which details the 1919 Black Sox scandal. Of course, Studs plays sportswriter Hugh Fullerton in the 1988 movie version of Asinof’s book, which means Studs is also mentioned in the Asinof papers.

The transcript for the Ciardi interview with underlined phrases.

When I became the director of the Museum’s Studs Terkel Center for Oral History in 2015, I grew even more curious about his interviewing style. What I use in oral history training sessions is this wisdom from him: “So I think the gentlest question is the best one, and the gentlest is, ‘And what happened then?’” I am constantly using that in my own interviews as we carry forward Studs’s legacy through the oral history center’s collaborative community-based projects. I also enjoy wearing red socks every workday to acknowledge his famous footwear.

Naturally, these eyewitness-to-Studs moments continue even during the pandemic. My daughter Lily recently finished her first year as a vocal jazz major at Western Michigan University. What did she watch as she finished the second semester from home? Of course, she watched Ken Burns’s documentary series Jazz (2001), featuring multiple interview excerpts of Studs. In April, Friedrich Von Steuben Metropolitan Science Center history teacher Meghan Thomas emailed me about her students conducting pandemic-related oral histories to replicate Studs’s interviews in Hard Times. Just recently, I saw a reference to him in a Chicago Magazine article about the city’s labor history.

Over the years, dozens of people have told me their eyewitness-to-Studs-stories. Many remember listening to his program on WFMT or watching him on television. Others have ridden the CTA with him or waited at the same bus stop. A journalist told me about a chance encounter he had with Studs that changed his entire career trajectory. Some people remember Studs interviewing friends or family or meeting him at book signings and other events. Today, all of us can pick up his books or listen to his recordings. What are your eyewitness-to-Studs stories?

Join the Conversation