Last summer, CHM collections intern Cara Caputo worked with collections manager Britta Keller Arendt to continue the ongoing inventory of the Decorative and Industrial Arts collection. This led her to discover just how much investigation working with the collection entails. CHM publications interns Lily Stachowiak and Brendan Narko helped organize and publish this blog post.

The primary goal of an inventory is to keep track of the artifacts in a museum collection. The process entails photographing each object and recording its location, dimensions, and physical description. During my summer internship, I had the opportunity to contribute to CHM’s ongoing inventory of its Decorative and Industrial Arts (DIA) collection. While I predicted that this project would allow me to discover several fascinating objects, I underestimated just how much detective work I would be performing.

My fellow intern and I soon learned that some objects in DIA storage are better documented than others. In most cases, an accession number is clearly written on or near the object, allowing us to connect the physical object with its record in The Museum System (TMS), which is the collections database, or CHM’s written records. Whenever an object is found without an accession number, however, this important link is missing. This is where the detective work begins as we attempt to determine the who, what, where, and when of an object.

The function of this flat, rectangular device was not immediately apparent to the collections interns. All photographs by Lily Stachowiak

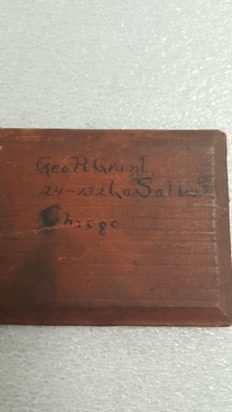

One particular mystery that we were determined to solve began when we found a flat, rectangular object that we first assumed to be a vintage mousetrap, as the object’s mechanisms and design matched our idea of modern mousetraps. Without an accession number, we searched for other markings and discovered a name and address on the back. This was the first clue that we would use in our investigation.

The back of the device was marked with the name and address of its owner, George R. Grant.

We assumed that this man was the donor, but when we searched the Museum’s records, we discovered no record of a George R. Grant donating anything resembling our mystery object. Upon further research, we learned that Mr. Grant was a prominent attorney in Chicago in the late 19th century. While this information did not immediately reveal the identity of the object, it nonetheless uncovered an important aspect of the object’s history.

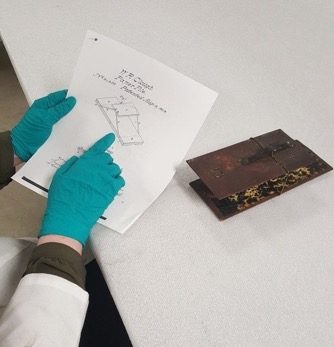

The next clues the object gave us were two patent dates, one from 1865 and the other from 1868. We began to search the United States Patent and Trademark database and compared the patents granted on each date in hopes of discovering patents that were issued to the same individual. After we failed to discover a match, we decided to examine the physical object for more clues. When we took a closer look at the text above the patent dates, we made out the words “bill holder.” Returning to the database, we refined our search to patents issued on each date that contained the keywords “bill” or “holder.” Sure enough, we soon discovered two patents that matched both the mechanisms and patent dates found on the object. We finally pieced together the mystery: this object combined two mechanisms in order to create an efficient bill holder that George R. Grant presumably utilized in the late 19th century.

The bill holder utilized two patented mechanisms, allowing its owner to store bills easily and securely.

Of course, we had to verify that our discoveries were correct, which we were able to do when we searched the TMS database and found a match for a “bill holder.” With our research and detective work, we updated this object’s TMS record and provided further information on the donor and the object itself, preventing future Museum staff from confusing this 19th-century bill holder with a mousetrap!