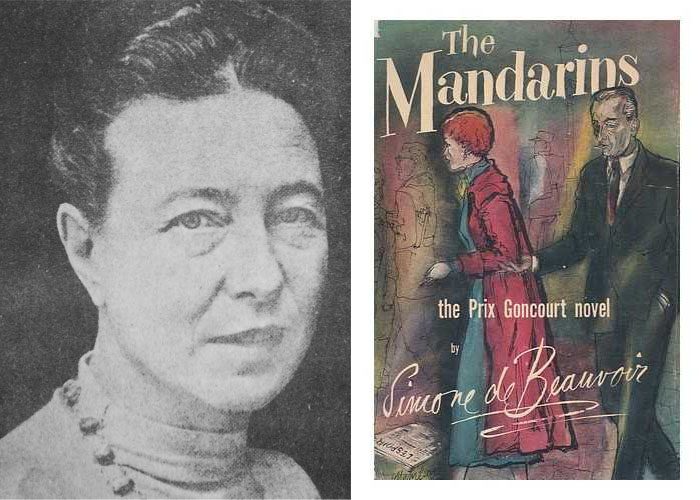

From left: Simone de Beauvoir, c. 1968. Wikimedia Commons; The Mandarins, 1st English-language edition, World Publishing Company, 1956; cover art by Laszlo Matulay

On this day in 1908, French writer and philosopher Simone de Beauvoir was born in Paris. She was a prolific and sometimes controversial writer who is perhaps best known for her seminal feminist text, The Second Sex (1949). While she was based mostly in Paris, Beauvoir traveled extensively and also spent time in Chicago. During a visit in 1947, she met writer Nelson Algren at the Palmer House hotel, which was the start of a brief but impactful romantic relationship between the two. A fictionalized account of their relationship is depicted in Beauvoir’s award-winning novel, The Mandarins (1954), which she dedicated to Algren.

The Mandarins covers the lives of a group of French intellectuals at the end of World War II through the mid-1950s based on Beauvoir’s experience, through the character Anne, navigating life, personal morality, and the political landscape after living through the Nazi occupation of Paris. Though she denied that the novel was a “roman à clef,” Beauvoir did say in her memoirs that the character of Lewis Brogan was based on Algren.

The novel covers Anne’s first meeting with Lewis in Chicago, where he takes her out to dinner at a pizzeria, to a burlesque show, and to listen to jazz at a dance hall. She claims that Lewis “knew everyone” and that it was the best evening she had spent in America. The experience mirrors the first meeting of Algren and Beauvoir, and the novel follows some of their subsequent travels together. Though their affair ended with some bitterness on Algren’s end, Beauvoir was buried with a silver ring on her finger that was a gift from Algren.

During Beauvoir’s relationship with Algren, he introduced her to his friend Studs Terkel, who in 1960 interviewed her about her upbringing and influences as an existentialist writer.

Studs Terkel Radio Archive

In his forty-five years on WFMT radio, Studs Terkel talked to the twentieth century’s most fascinating people. His radio program, with its deeply rooted humanistic approach to the big questions of human life and social organization, was filled with philosophical inquiry and search for deeper meaning. That said, Terkel did not interview a large number of actual philosophers about specifically “philosophical” books or debates. Instead, listeners will find remarkably similar approaches to the pursuit for metaphysical, ethical, or aesthetic understanding, whether the conversation is with a celebrated philosopher like Bertrand Russell or a group of teenagers living on the West Side of Chicago.