“In seas. In windsweep. They were black and loud.

And not detainable. And not discreet.”

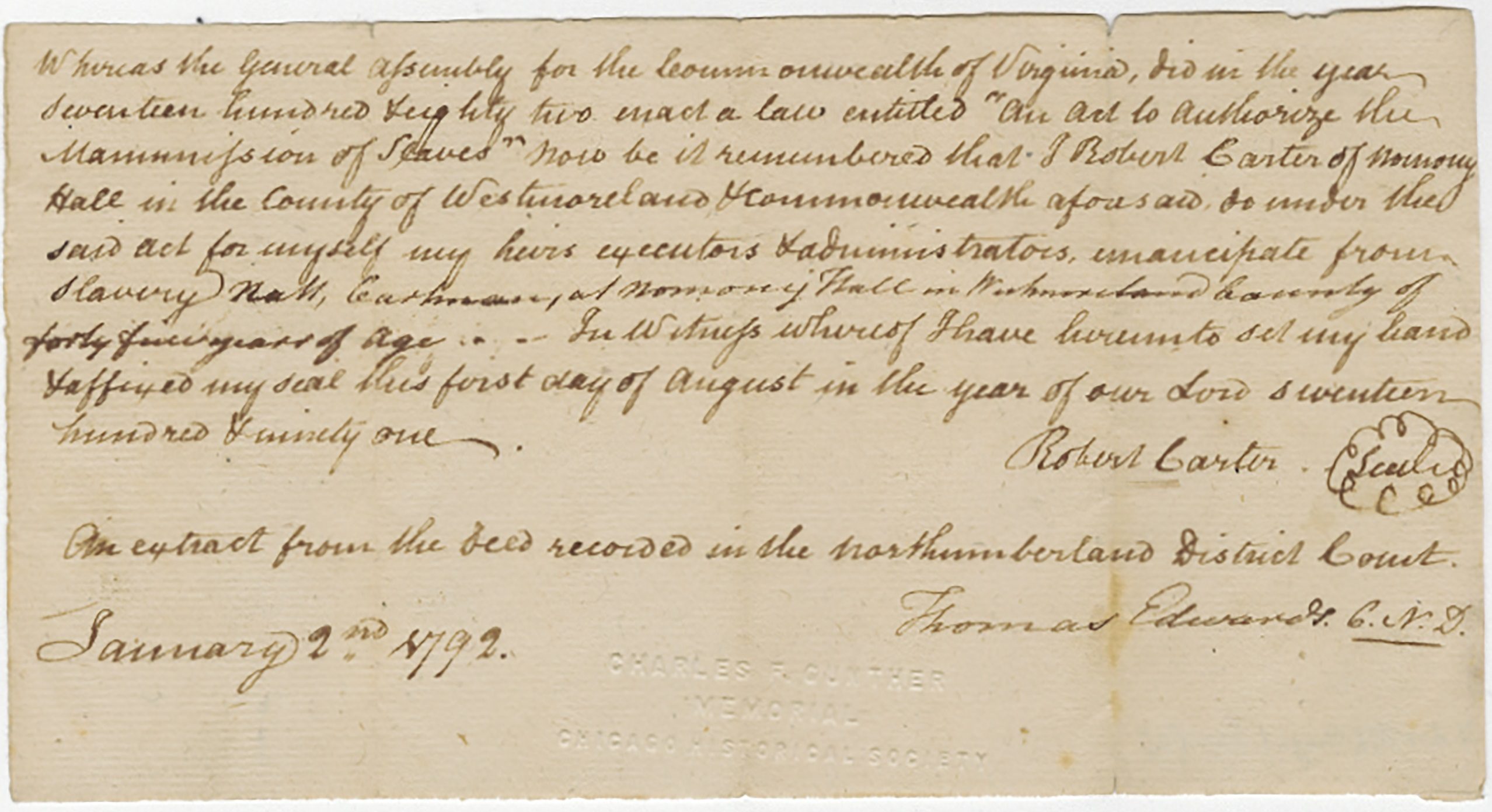

— Gwendolyn Brooks, Riot (Detroit: Broadside Press, 1969)

As the Digital Humanities Curatorial Fellow at CHM charged with developing digital storytelling initiatives using the Museum’s collections items, I face questions about language within metadata (detailed information on an item to help users discover resources) daily. One particularly charged term appearing throughout the digitized collections is “riot.” CHM is currently undergoing a critical analysis of riot terminology within our descriptive metadata—found in the ARCHIE catalog records, CHM Images, and other digital resources used by researchers—with the intention of updating records to represent their historical content more equitably. Language changes, such as the ones for “riot” and “uprising,” fall under the umbrella of CHM’s Critical Cataloging initiatives. This blog post considers Chicago’s “riot” history, the term’s use within the descriptive metadata of digitized collections items at CHM, and best practices for appropriate use and corrective language.

Cover of Riot by Gwendolyn Brooks, 1969. CHM, ICHi-182532b

Perhaps the most iconic usage of the term “riot” is in the title of Gwendolyn Brooks’s three-part poem, published by Broadside Press in January 1969. In Riot, Brooks describes the global Black community’s response to the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Brooks’s poem gives meaning to a community “in windsweep,” “black and loud,” as does the frontispiece “Allah Shango” (not pictured) by AfriCOBRA artist collective cofounder Jeff Donaldson. In the painting, two young Black men are shown both trapped behind, and shattering through, a glass window. Brooks’s poetry and Donaldson’s painting depict rioting as a strategy for gaining access to that which has been rendered inaccessible, for giving voice to issues that have been systematically silenced. According to historian Felix M. Padilla, riots follow a pattern: following an influx of population, there are increases in racial violence and legislative acts to prevent movement into white neighborhoods. Overcrowding, disease, police brutality, and violence create the psychological climate for rioting.

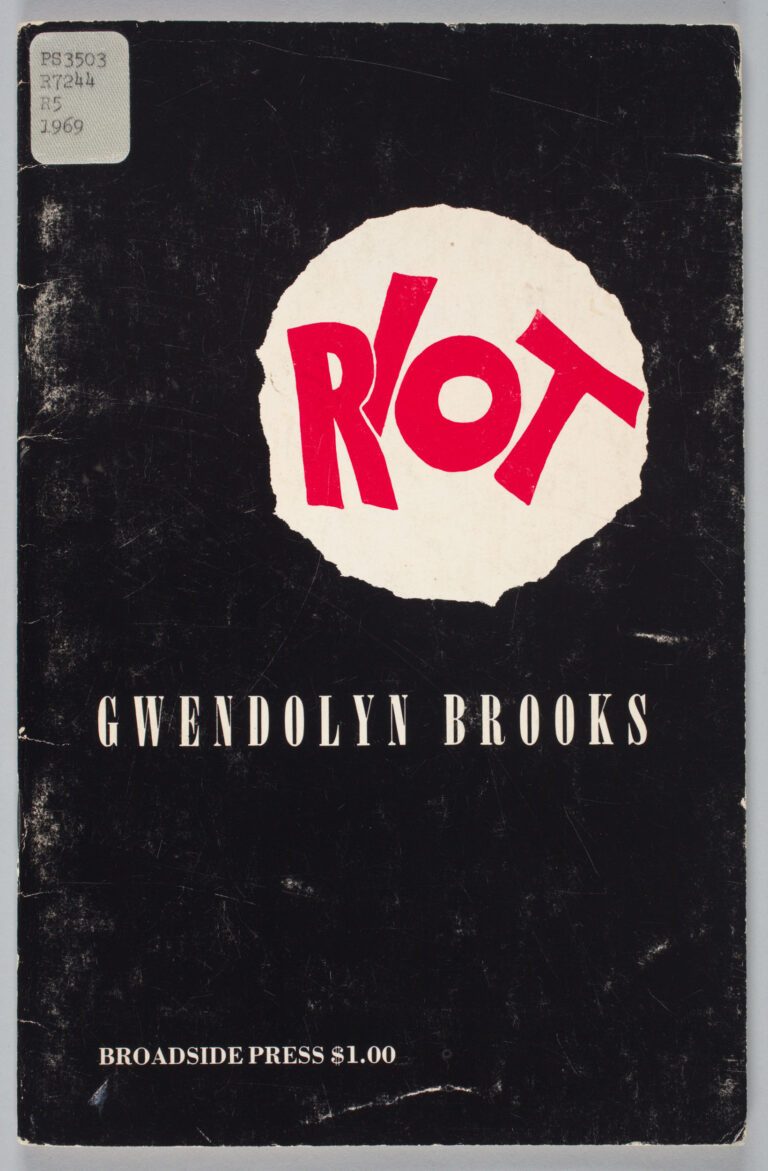

For Black communities of Chicago in the 1960s, this included limited access to adequate housing, health, education, and employment, illuminated by Dr. King when he moved to North Lawndale in 1966 to work with the Chicago Freedom Movement. Visuals created by the Chicago Freedom Movement such as the “MOVE” logo highlight the power of art and design as an agent of protest and advocate for social justice. CHM’s upcoming exhibition, Designing for Change: Protest Art of the 1960s‒70s, explores how Chicagoans used art to advance the Chicago Freedom, Black Power, anti-Vietnam War, women’s liberation, and early LGBTQIA+ movements. Dr. King and the Chicago Freedom Movement used design to visually engage audiences, raise awareness of poor living conditions, and fight against blockbusting, predatory lending, and the dual housing market.

Left: Recto of Chicago Freedom Movement flyer, We Are Here Because, opposing discriminatory real estate practices, Chicago, 1966. CHM, ICHi-183258-001. Right: Cover for the program for the Chicago Freedom Festival with Chicago Freedom Movement symbol on front cover, sponsored by Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Coordinating Council of Community Organizations, held at the International Ampitheatre, 4220 South Halsted Street, Chicago, March 12, 1966. CHM, ICHi-182985

Photographs depicting the civil response to King’s murder, known as both the “King Assassination Riots” and “Holy Week Uprising,” speak to the complexities of language. Images of burning and vandalized buildings, shattered storefronts, littered streets, and armed guards inspire visceral responses from their viewers. But as asserted by Darnell Hunt, Dean of Social Sciences and Professor of Sociology and African American studies at UCLA, the terms “rioting” and “looting” connote senseless violence and crime and diminish or obscure the underlying racial oppression and demonstrative purposes of such acts. According to activist Toivo Asheeke, the term riot “holds an inordinate amount of importance on whether one interprets events as justified or not.” Furthermore, the word riot has become a racist trope, according to Dr. Elizabeth Hinton, applied to events properly understood as uprisings or rebellions, that is, collective resistance against an unequal and violent order.

Though sometimes used interchangeably, riot, rebellion, protest, and uprising have been loaded with racial connotations by the media and public throughout history. It is not only who, but how these events are depicted, that generates meaning for viewers. In 2018, previously unsurfaced photographs of the days after King’s assassination taken by Karega Kofi Moyo were displayed at a gallery in the Pilsen neighborhood in the Lower West Side community area. The photographs show a unique perspective of the event compared to the mainstream (white) media publications to date, including an image of a lone young boy covering his face near a group of armed guardsmen in gas masks. Photographs like these illustrate the military-backed violence committed toward the Black community, a tragic and deadly reality of uprisings that is undermined by the term “riot.”

A National Guardsman aims his rifle on West Madison Street during riots following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Chicago, April 6, 1968. ST-17500739-E1, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

When used to describe collective events in Chicago history with distinctive motives and outcomes, the term riot sends conflicting messages. The digitized Chicago Sun-Times collection at CHM, and its descriptive metadata, shed light on this issue. Of the digitized images in this collection, 640 contain the word “riot” in their metadata, and 17 contain the word “uprising.” The term “riot,” often transcribed from the photographer’s original caption, was used to describe the 1919 Chicago Race Riot, the 1966 “Puerto Rican/West Side riots,” the 1977 “Humboldt Park riots,” the 1968 “Democratic Convention riot,” and the 1968 “Martin Luther King Jr. Assassination riots” alike, despite their varied motivations and outcomes. The Chicago Sun-Times collection is part of the archives that CHM is currently studying to specify terminology and correct such conflations.

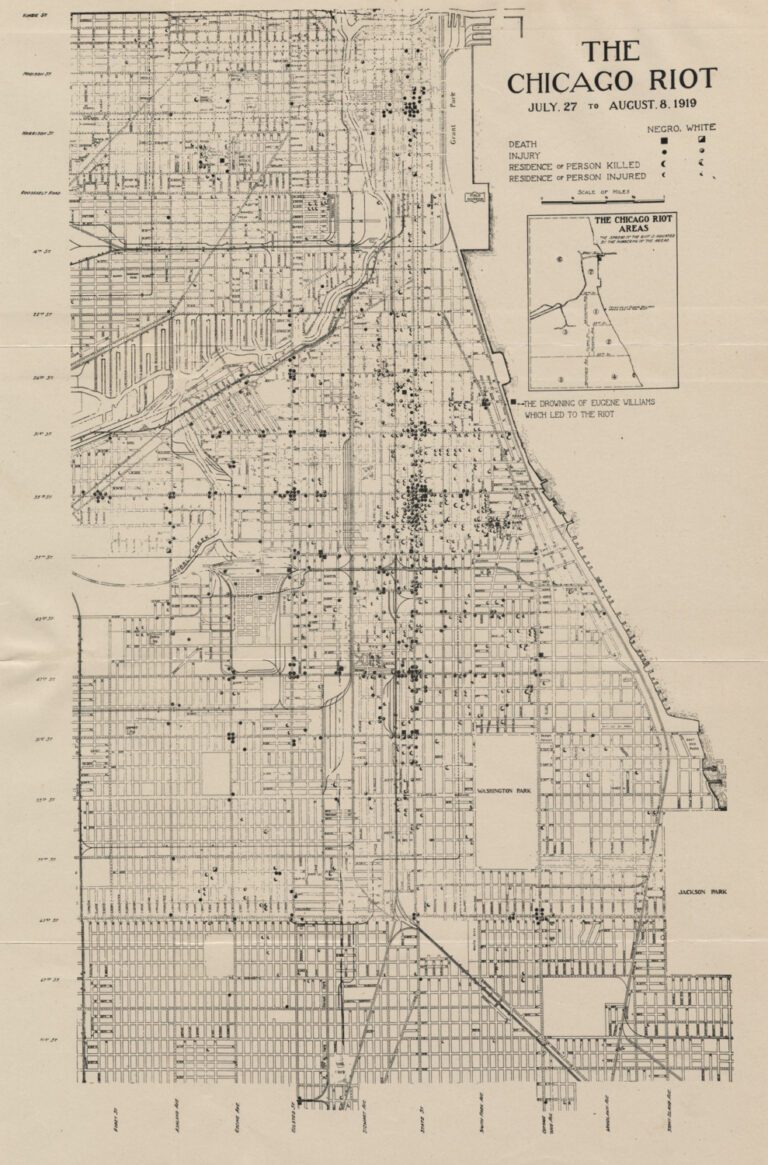

Left: Neighborhood children raiding an African American family’s house after they were forced out during the 1919 Chicago Race Riots, Chicago, 1919. CHM, ICHi-040052; Jun Fujita, photographer. Right: Map of titled The Chicago Riot indicating that most of the fighting occurred between 35th Street and State Street from July 27 to August 8, 1919. CHM, ICHi-040053

In the first half of the twentieth century, riot was frequently used to describe white mobs committing violence against Black people and homes. Following the murder of Eugene Williams by a white mob for floating into a “white” beach, and the violence that erupted into the 1919 Chicago Race Riots, more than 2,800 officers surrounded the Black Belt (a corridor of predominantly Black neighborhoods along State Street), effectively concentrating the violence and its material effects within Chicago’s Black community. Black people were charged with crimes at double the rate as white people, despite suffering two-thirds of casualties resulting from the riot.

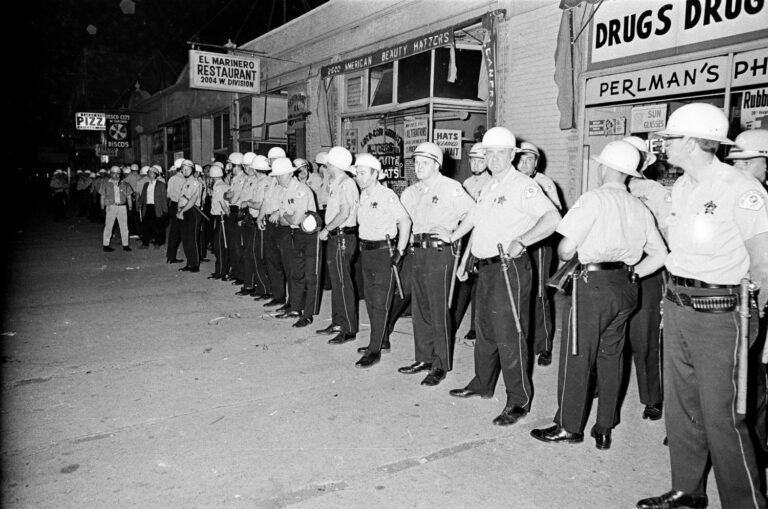

Police presence during riot in Puerto Rican community on Division Street near Hoyne Avenue, Chicago, June 13, 1966. ST-11007177-0006, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

In the 1960s the term riot was applied instead to insurrections against police and institutions, as with the “1966 Puerto Rican/West Side riots.” With the planned redevelopment of Lincoln Park and expansion of DePaul University’s campus in the 1950s and ’60s, Puerto Rican residents were pushed out from their homes and neighborhoods into overcrowded and unsanitary areas to the west. As a response to organized displacement and police brutality against Puerto Rican communities, the 1966 West Side “riots” were motivated by oppression—and therefore, appropriately understood as a “rebellion” or “uprising” distinct from racially-motivated violence like the 1919 Chicago Race Riots.

Members of The Woodlawn Organization (TWO) picket outside of the Polish Roman Catholic Union offices, 984 North Milwaukee Avenue, regarding the desperate need of maintenance work on a 20-unit apartment building in the Woodlawn community area, Chicago, June 11, 1964. ST-10003494-0014, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

As historians, we must be cautious of language used to analyze, marginalize, or mischaracterize the racially discriminated, poor, or disenfranchised, in the past. This includes making distinctions between riot and uprising, one connoting senseless violence, and the other, a collective fight against oppressive systems. Similarly, we must question terms like “ghetto,” “slum,” and “underclass,” which, as with “riot,” have not only been used to describe existing conditions but have contributed to neighborhood disinvestment and decline.

Bibliography

- Paul Bisceglio, “There’s a Difference between Riots and Rebellion,” UCLA Newsroom, July 13, 2015.

- Chicago History Museum. “It Was a Rebellion: Chicago’s Puerto Rican Community in 1966.” Google Arts & Culture.

- Alia E. Dastagir, “’Riots,’ ‘Violence,’ ‘Looting’: Words Matter when Talking about Race and Unrest, Experts Say,” USA Today, May 31, 2020.

- KT Hawbaker, “K. Kofi Moyo Exhibits Scenes of Resistance from Chicago’s Past that Mirror the Present,” Chicago Tribune, August 16, 2018.

- Elizabeth Hinton, America on Fire: The Untold History of Police Violence and Black Rebellion Since the 1960s (New York: Liveright, 2022).

- Ann K. Johnson, Urban Ghetto Riots, 1965–1968 (East European Monographs, 1996), distributed by Columbia University Press.

- Felix M. Padilla, Puerto Rican Chicago (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1987).

- Abigail Perkiss, “The Language of Protest: Race, Rioting, and the Memory of Ferguson,” Yahoo! News, December 3, 2014.

- Ben Railton, “What We Talk About When We Talk About ‘Race Riots,’” Talking Points Memo, November 25, 2014.

- Carl Sandburg, The Chicago Race Riots (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Howe, 1919).

- Jackie Spinner, “Fifty Years after Chicago ‘Riot,’ New Photos Emerge—and Develop a Story,” Columbia Journalism Review, March 7, 2018.

- Heather Ann Thompson, “Urban Uprisings: Riots or Rebellions?” in The Columbia Guide to America in the 1920s (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001), 109–17.

- William M. Tuttle, “Contested Neighborhoods and Racial Violence: Prelude to the Chicago Riot of 1919,” Journal of Negro History 55, no. 4 (1970): 266–88.

- David Wyatt, “Chicago,” in When America Turned: Reckoning with 1968 (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2014), 231–54.

- Heather Yarrish, “White Protests, Black Riots: Racialized Representation in American Media,” Young Scholars in Writing 16 (August 2019): 6–24.