CHM curatorial assistant Brittany Hutchinson reflects on her work for our newest exhibition, Remembering Dr. King: 1929–1968.

The entrance to Remembering Dr. King. Photograph by CHM staff

At the Chicago History Museum, we are honoring the life and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. with an exhibition, Remembering Dr. King: 1929–1968. It includes objects and images that reflect his work nationally and locally and asks visitors to think how they are carrying his legacy today.

Dr. King often spoke of the inherent connection between all people despite the circumstances that attempt to separate us. The exhibition explores connections between Dr. King’s life and the events taking place in the world around him. Along the perimeter wall of the gallery, a timeline follows Dr. King’s historic rise to prominence, the height of his leadership in the civil rights movement, and finally his untimely death at the hands of a white supremacist. It becomes clear that at the height of his popularity, the world that once influenced Dr. King begins to change as it became influenced by him.

The large images are arranged in an intricate grid. Photograph by CHM staff

Suspended in the center of the gallery are images related to Dr. King’s activism in Chicago. Along with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), he left the South in 1965 and announced the Chicago Campaign, establishing the Chicago Freedom Movement in order to continue the fight against racism. Determined to challenge Chicago’s closed-housing market, Dr. King moved his family to the North Lawndale neighborhood to draw attention to the conditions that Chicago’s black citizens faced. Along with local activists, he participated in open-housing marches in white neighborhoods around the city. In every instance, activists were met with anger and violence. At one march, Dr. King was struck with a rock thrown by a counterprotester in the Marquette Park neighborhood.

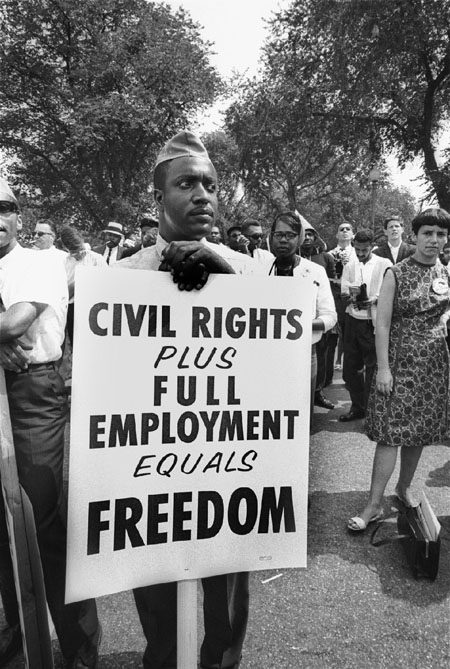

A protester holds a sign during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, Washington, DC, August 28, 1963. Photograph by Declan Haun, ICHi-036879

The end of the Chicago Campaign in late summer 1966 signaled a shift in Dr. King’s focus as well the public’s opinion of him. In spring 1967, he delivered an antiwar sermon, “Beyond Vietnam,” at Riverside Church in New York City. That same year, he announced the Poor People’s Campaign, a plan to unite the nation toward economic equality and justice. Activists from multiple racial backgrounds pledged to join Dr. King in the fight to uplift the American working class through securing fair wages, full employment, and economic empowerment. The combination of an antiwar and anticapitalist platform hurt Dr. King’s already waning popularity.

Following news of Dr. King’s assassination, massive riots broke out in Chicago and several other US cities, April 1968. Photograph by Declan Haun, ICHi-062889

Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated by James Earl Ray at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 4, 1968. Response to his murder was swift and violent, and Chicago was especially impacted. The day after Dr. King’s assassination, uprisings erupted across the city. The National Guard was called in to patrol the city until order was restored on the following Monday.

Mourners gather at the funeral for Dr. King in Atlanta, April 9, 1968. Photograph by Declan Haun, ICHi-062906

Dr. King’s influence on American society continued on after his death. One week after his assassination, Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Federal Fair Housing act of 1968 into law. In November 1983, Ronald Regan signed the King Holiday Bill establishing that, beginning in 1986, every third Monday of January should be observed as a national holiday. Dr. King’s legacy lives on as each year we celebrate his life by asking ourselves how we can help to continue his fight against inequality and toward freedom.