To kick off Monday Night Nitrates, our new weekly photograph series, M. Alison Eisendrath, CHM’s Andrew W. Mellon Director of Collections, describes the effort to assess, preserve, and digitize our collection of approximately 35,000 nitrate negatives.

In 1889, the Eastman Kodak Company introduced the first commercially available cellulose nitrate film as an alternative to the more fragile and cumbersome glass plate negatives in common use at the time. Offering deep blacks, bright whites, and rich tonal detail in addition to ease of use, nitrate film became the medium of choice for amateur and professional photographers during the first half of the twentieth century.

Taken at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, this photograph is an early example of the use of nitrate negatives. CHM, ICHi-170220; photograph by C. P. Rumford

Nitrate film had its downsides, however. It turned out to be extremely unstable and highly flammable—even capable of spontaneously combusting when stored in large quantities. Thus, nitrate negatives have posed some unique challenges for museums seeking to preserve them.

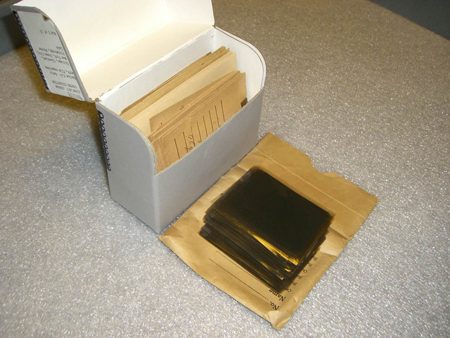

Close-ups of some nitrate negatives in our collection. Photograph by CHM staff

This past year, the Chicago History Museum secured a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) to digitize and preserve our collection of approximately 35,000 nitrate negatives. This priority initiative is the culmination of a five-year journey of assessment, research, and planning that began—oddly enough—with a roofing project.

For many years, for the safety of our staff and collection, CHM’s nitrate negatives were kept in a cold storage vault atop our Clark Street building, until roof repairs meant that the vault’s cooling system would need to be dismantled. As the collections staff transferred the nitrate negatives into temporary storage, they faced the challenge of how to manage this material going forward:

- What was the ideal environment for storing the nitrate negatives, and could those conditions be achieved at our facility? Could the negatives be stored safely over time and within a realistic budget?

- What was the current condition of the negatives and were the images still viable?

- How historically significant were the negatives anyway? Did they merit the expenditure of time and money required to ensure their long-term preservation?

- And, if they were indeed significant, how could we create access to this largely untapped resource while also preserving them for the future?

A section of nitrate negatives in temporary storage. Photograph by CHM staff

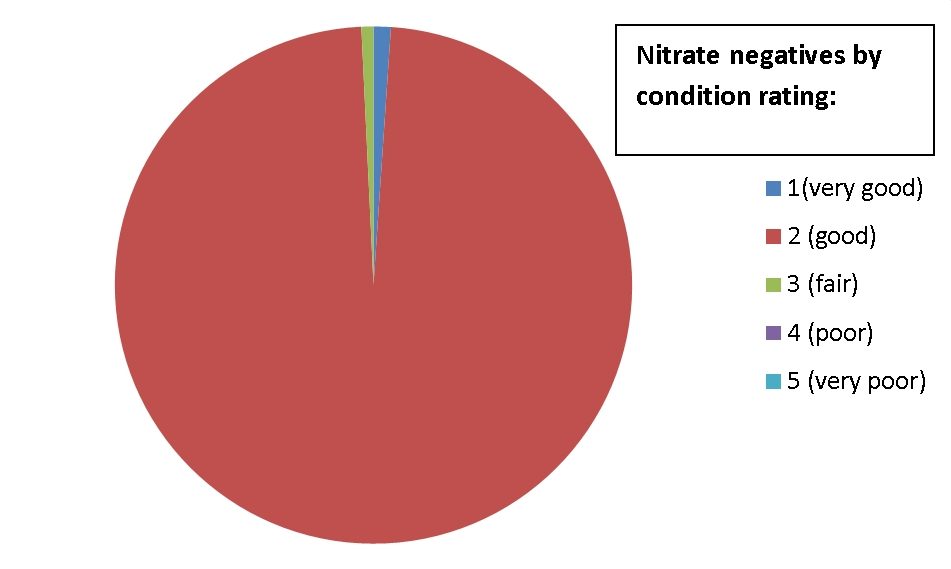

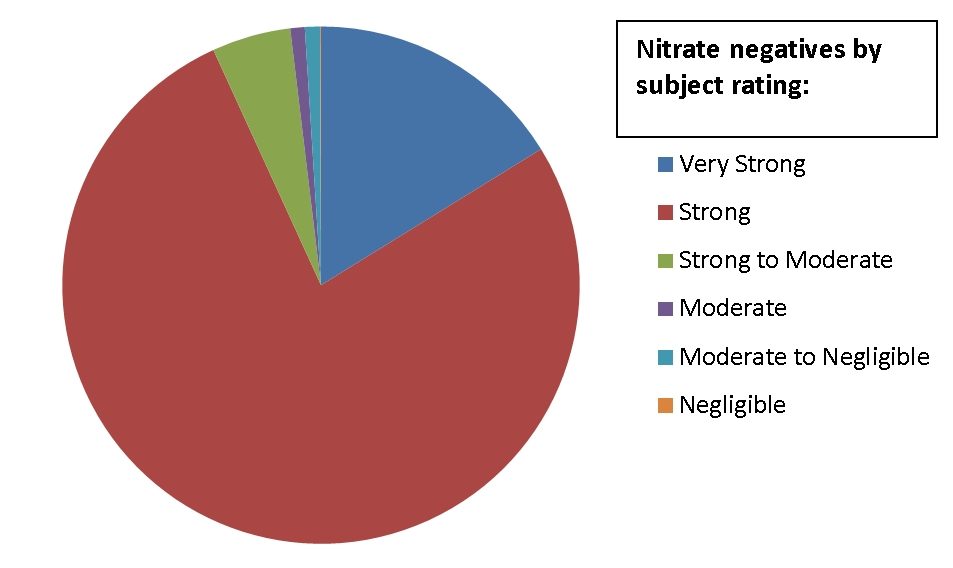

To answer these questions, CHM submitted a proposal to the Gaylord and Dorothy Donnelley Foundation in 2012 and was awarded a planning grant to undertake a comprehensive nitrate negative condition survey and content assessment and to hire as an outside preservation consultant Henry Wilhelm, one of the nation’s foremost experts on cold storage of photographic materials. After a two-year evaluation, CHM staff determined that the vast majority of our nitrate negatives were still in reasonably good condition and that many of them also had strong research value and use potential.

The Donnelley-funded assessment yielded a positive report on the nitrates.

In his 209-page report, Wilhelm laid out an implementable storage plan to effectively arrest the negatives’ chemical degradation and eliminate the risk of fire. He also strongly urged CHM to digitize the negatives not only to create access to the materials, but also to reduce the need for handling of the originals.

Information gleaned from the Donnelley project proved invaluable in securing IMLS funding to implement Wilhelm’s recommendations. Also necessary was the development of innovative new digitization, description, and discoverability solutions to support digitization on such a large scale—strategies that will be described in greater detail in subsequent blog posts. After many years of active planning and activity, the project team is thrilled to begin sharing the results of our labors!