Latest Posts

With the city’s unpredictable Midwestern weather, Chicago’s outdoor athletes have had to get creative when it comes to staying active indoors. In this blog post, editor and content manager Heidi Samuelson writes about the rise and fall of indoor baseball and its continued legacy.

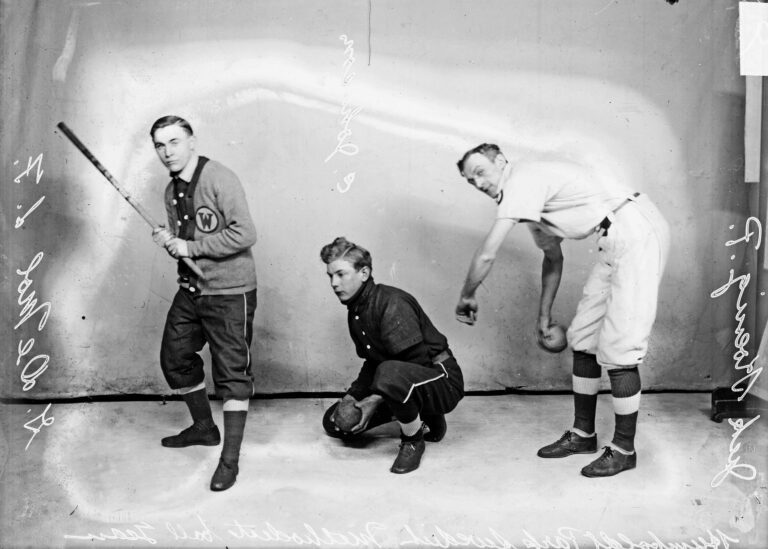

Portrait of G. De Mol (holding a bat), E. Johnson (kneeling), and Jack Hoenig (pitching stance) of the Humboldt Park Swedish Methodist indoor baseball team, 1909. SDN-007248, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

Indoor baseball originated on Thanksgiving Day 1887 by George Hancock, a reporter at the Chicago Board of Trade, at the Farragut Boat Club on Chicago’s South Side. The story goes that he went to the club to find out the score of the Yale-Harvard football game, where a group of Yale and Harvard alums were following the game via telegram. Yale lost the game. After a Yale alumnus jokingly threw a boxing glove at another member who batted it away with a stick, Hancock got the idea to draw a diamond on the gymnasium floor. With a rough set of rules, the members began playing the first game of “indoor baseball” with a tightly wrapped glove and a stick. By winter’s end, the boat club was playing games with other clubs.

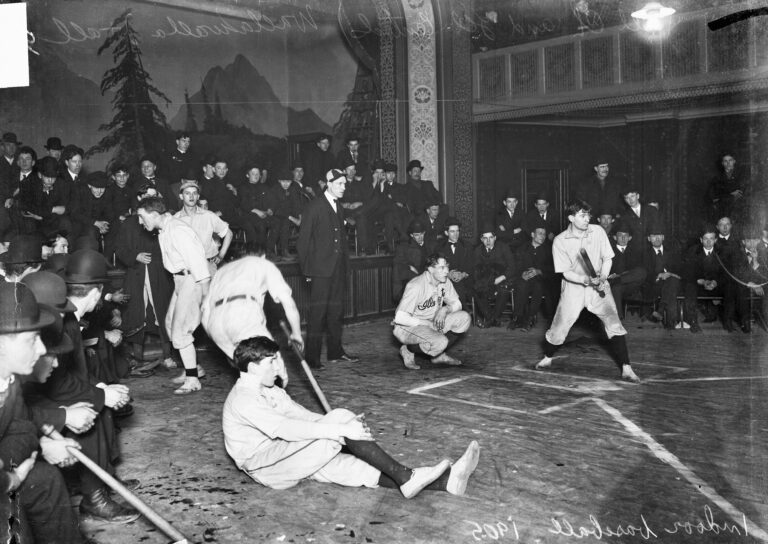

Chicago-Illinois Central indoor baseball game in a gymnasium, Chicago, 1905. SDN-003190, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

The basic equipment for “indoor baseball” was a soft 17-inch ball and a thin, stick-like bat. Players didn’t wear gloves, the bases were placed 27 feet apart (compared to 90 feet apart on an outdoor baseball diamond), and the pitcher was only 22 feet from home plate. The game appealed to rowers, who were stuck indoors in winter months, but it soon spread across the Chicago area. By winter 1891–92, there were more than 100 teams organized in amateur leagues.

Group portrait of members of the Rogers Park girls’ indoor baseball team, 1909. SDN-007848, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

Colleges and high schools, girls and boys, began to embrace the sport a few years later in December 1895, when 10 schools formed a league. Indoor baseball was particularly popular on the city’s West Side, and English High (later Crane Tech), Medill, and West Division (later McKinley) were dominant in league play. In 1899, West Division formed a girls’ league, having started playing intermural games in 1895, which included the West Side’s Marshall and Medill.

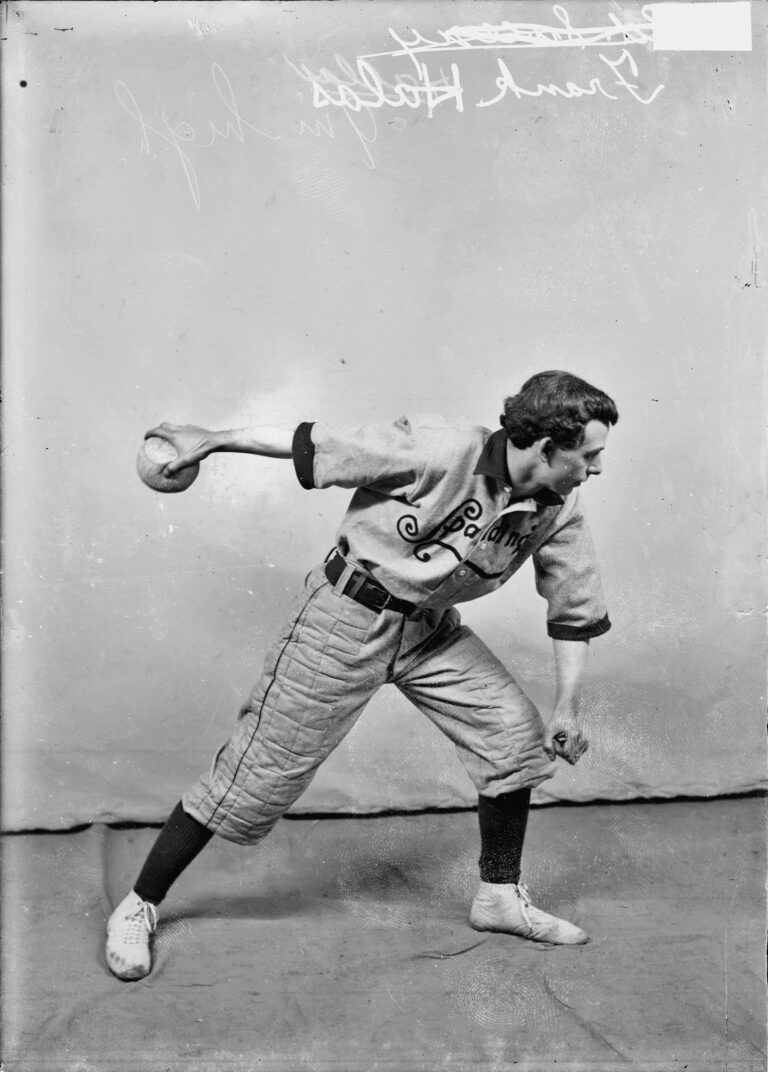

Frank Halas, indoor baseball player, winding up for a pitch, 1907. SDN-005286, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

The sport was particularly popular among Czech Americans. Among its notable players were the Halas brothers, including George Halas, future owner of the Chicago Bears. George’s older brothers Frank and Walter were both standout players. The Halas brothers played at Crane Tech, and Frank also played in the Chicago Indoor Baseball League.

Around 1907, players began moving the game outdoors, changing the name to “playground ball” and later “softball.” In the 1910s, the indoor version declined in popularity, due to the rapidly growing popularity of basketball, and by the 1920s, indoor baseball was essentially nonexistent.

However, its legacy continued through 16-inch slow-pitch softball, sometimes called Chicago ball. The first 16-inch softball national championship was held during the 1933–34 A Century of Progress world’s fair. From there, a professional league formed, which existed through the 1950s. The sport is still played in Chicago today in recreational leagues, and you can visit the 16 Inch Softball Hall of Fame in Forest Park, Illinois.

Additional Resources

- Encyclopedia of Chicago entry on Indoor Baseball

- Encyclopedia of Chicago entry on Softball

- “Indoor Baseball in Chicago High Schools, 1892 to 1919” by Robert Pruter

- “Chicago High School Girls Pioneer Indoor Baseball for Women” by Robert Pruter

- See more images of indoor baseball on CHM Images

CHM senior public and community engagement manager Gregory Storms recalls the life of Mama Gloria Allen, an African American transgender activist, and her impact on Chicago’s LGBTQIA+ community.

In late 2011, I moved to Chicago to research segments of the city’s LGBTQIA+ community and its history. Soon after I moved here, I was connected to Center on Halsted, the Midwest’s largest LGBTQIA+ community center, which is located in the Lakeview community area. A couple years later, I found myself working there overseeing Youth Services and engaging LGBTQIA+ young folk, especially those experiencing homelessness. Unsurprisingly, a disproportionate number of those individuals are gender expansive, nonbinary, and/or transgender. It was also during this time that I met Gloria Allen, affectionately known to everyone around her as “Mama Gloria.”

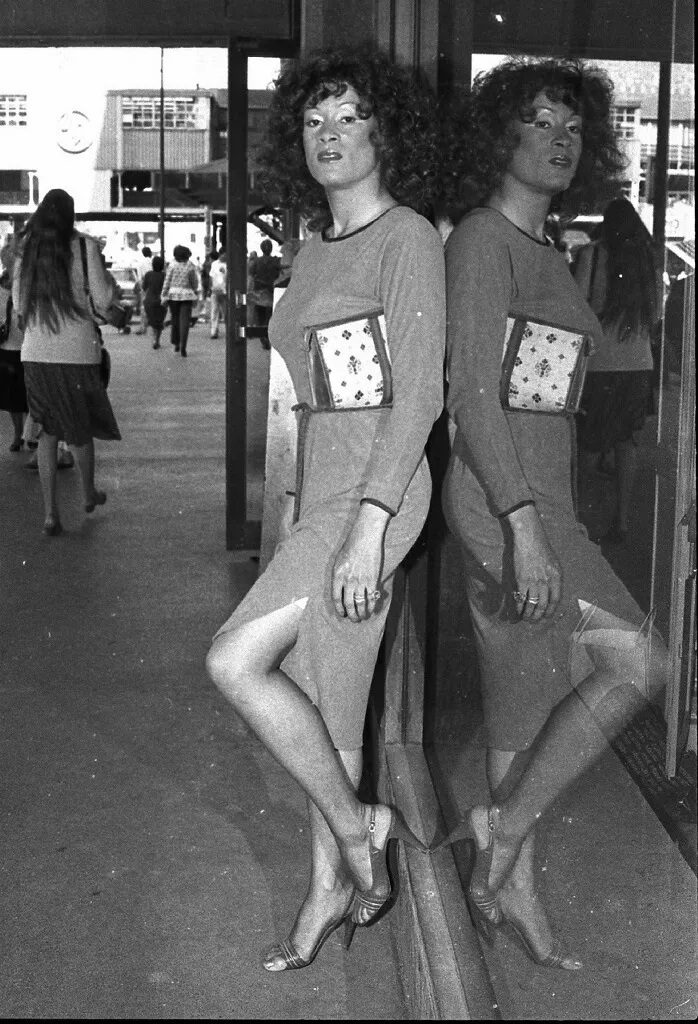

Gloria Allen, c. 2022. Image from Wikimedia.

Mama Gloria was an African American transgender woman who left an indelible mark on our community. I first heard about her and her “Charm School” through Youth Services staff before meeting her in person.

Center on Addison at 806 N. Addison St. (left) is part of Center on Halsted, serving as a space for Senior Services programming for LGBTQIA+ older adults. It is connected to Town Hall Apartments (center background), a senior living facility where Gloria Allen lived in her later years.

Charm School was a workshop Mama Gloria offered primarily to young folks of transgender experience as a sort of lesson in etiquette. As she said, “Manners are important to me. You have to know how to talk to a person, listen to them, and have fun with them.” But these lessons weren’t really about etiquette alone. They were an opportunity to forge new intergenerational relationships, to offer these young people a role model, an elder to whom they could look with respect. This was especially important given how few elder transgender role models are still with us today. As Mama Gloria herself would often recount, transgender women were “either beaten or murdered,” something that many younger transgender people today think will happen to themselves, too.

Center on Addison was formerly the Chicago Police Department Town Hall station in Lakeview, one of many locations in Chicago where LGBTQIA+ folks were incarcerated in earlier decades, making its transformation into a LGBTQIA+ senior living center an important symbolic victory for the community.

These young folks were able to benefit from Gloria’s long and full life. Born October 6, 1945, in Bowling Green, Kentucky, and raised in Chicago, she was fortunate to have a supportive family. Her mother, Alma Dixon, was a source of lifelong support and affirmation. Her maternal grandmother, Mildred, was also pivotal in Gloria’s life. Both women worked in and around the entertainment industry. Alma was a showgirl and Jet magazine centerfold; Mildred was a seamstress who often did work for drag queens and male strippers during Gloria’s youth. Both knew transgender women through their work before the word transgender was even coined decades later. (For example, Merriam-Webster Dictionary states the first known use of “transgender” was in 1974.) Other members of her extended family also supported her transition and remained close throughout her life.

Gloria Allen, c. 1970. Image from Block Club Chicago

Still, even with family support, Mama Gloria faced a number of life challenges as an African American transgender woman growing up in the mid-twentieth century. Facing hate-motivated violence and harassment, domestic violence, barriers to educational and employment opportunities, and a gradually developing system to support social and medical transition, Gloria Allen was confronted with significant challenges. Despite these challenges, however, she lived her life the way she wanted and became a beloved member of Chicago’s LGBTQIA+ community.

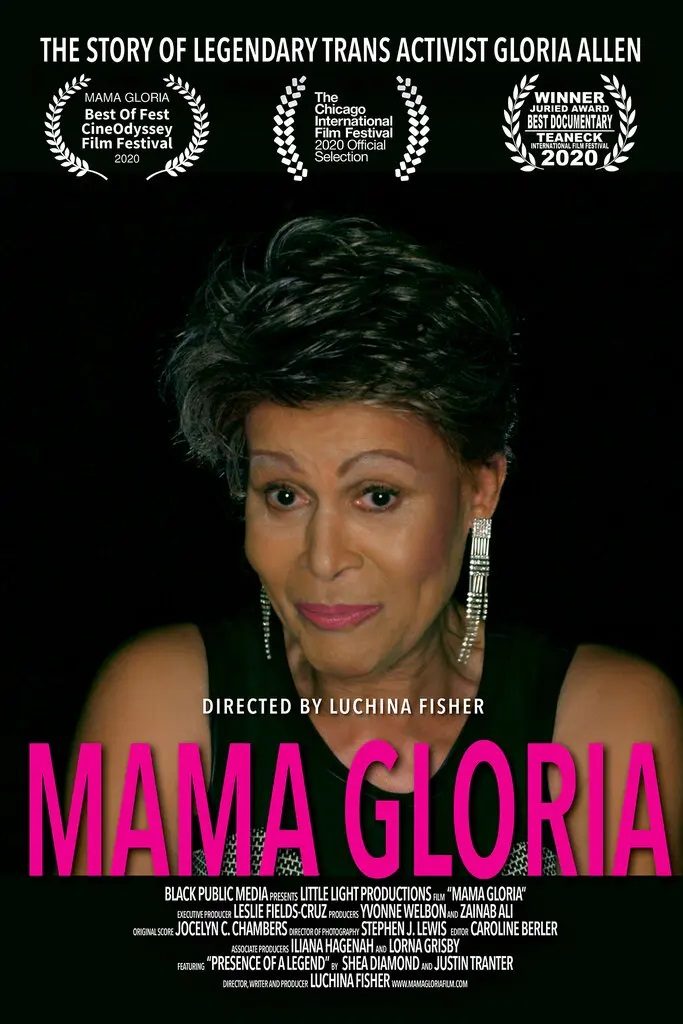

Her Charm School gained journalistic attention, which later led to new opportunities like a theatrical play by Philip Dawkins, Charm, based on her life. She was recognized by transgender writer and activist Janet Mock at the Trans 100 Awards in 2014 and was the subject of a 2020 documentary about her life called Mama Gloria.

The cover of Mama Gloria. The film was nominated for a 2022 GLAAD Media Award.

Sadly, Gloria Allen died on June 13, 2022, at the age of 76. I clearly remember learning of her death from friends and colleagues. It was a loss to the entire community, but her memory lives on in the lives of the young folks who were fortunate enough to know, learn from, and love her like the chosen mother that she was.

Additional Resources

- Our Abakanowicz Research Center houses the Gloria Allen papers [manuscript], approximately 1945–2022

- Watch Mama Gloria on PBS (free streaming through April 30, 2024)

- Learn more about The Trans 100 and read their publication from 2014 featuring Mama Gloria

- Read GLAAD’s “Glossary of Terms: Transgender” in their Media Reference Guide – 11th Edition

- Learn more about the Center on Halsted

For Christians around the world, Palm Sunday marks the start of Holy Week leading into Easter Sunday. In this blog post, CHM curator of religion and community history Rebekah Coffman writes about the Polish traditions behind the day and when Polish president Lech Wałęsa attended a Palm Sunday Mass in Chicago in 1991.

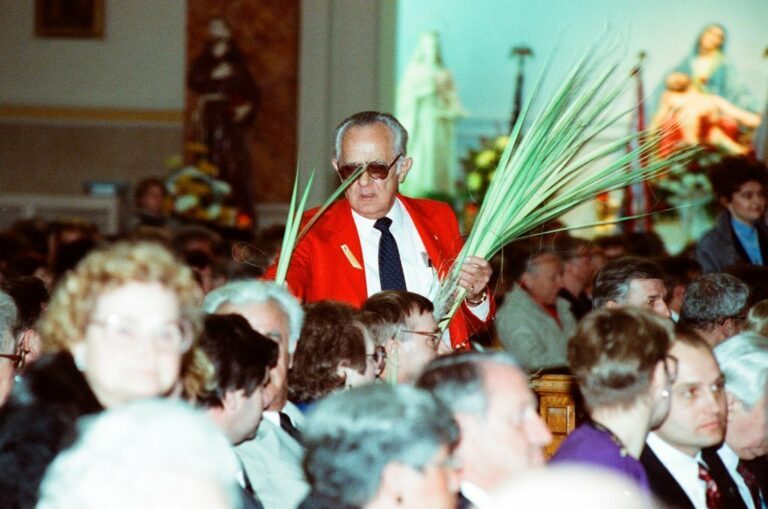

An usher distributes palm fronds at Palm Sunday Mass at St. Hyacinth Basilica, 3636 W. Wolfram St., Chicago, March 24, 1991. ST-19041696-0220, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

In Christianity, Palm Sunday commemorates Jesus’s entry to Jerusalem when he was greeted by crowds waving palm branches. Many churches today across Christian denominations distribute palm fronds during services as preparation for the coming reminder of rebirth and life overcoming death.

Palm Sunday in Lipnica Murowana, Poland, 2004. Maciej Szczepanczyk, Wikipedia Commons.

In Polish tradition, processions of palms take a major step beyond waving a single green branch. In fact, because palms are rare in Poland, palm branches are sometimes forgone completely, and beautiful bundles of willow (wierzba) and colorful bouquets of dried flowers are used instead. These incredible bundles are used in Sunday church services and afterward may be brought home or planted in fields as symbols of good luck. Some areas in Poland take decorating palms to a whole new level and hold annual contests for the tallest and most decorative display.

Palm traditions have extended here to Chicago, as can be seen in these images from a Palm Sunday service at St. Hyacinth’s Basilica (Bazylika Świętego Jacka) in the Avondale community area. St. Hyacinth’s was founded in 1894 by a group of Resurrectionists from St. Stanisłaus Kostka. Initially in a modest wood building, the congregation’s impressive Polish Cathedral-style church was built from 1917 to 1921.

Overhead view of parishioners celebrating a mass at St. Hyacinth Basilica, Chicago, December 11, 1983. ST-19041501-0006, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

The area of Avondale surrounding St. Hyacinth’s is also known as “Jackowo,” which when paired with the area surrounding nearby St. Wenceslaus Church (known as “Wacławowo”), is more generally known as the Polish Village. Avondale is historically known as a working-class neighborhood, developing along the Chicago River, rail lines, and brick factories. Beginning in the 1870s, a community of Black families in the Dawson subdivision called Avondale home. In the next few decades, the neighborhood quickly shifted as an influx of European migrants from Germany, Sweden, and Austria followed.

Pedestrians on North Milwaukee Avenue in Avondale, Chicago, January 24, 1975. ST-90003274-0020, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

By 1930, nearly a third of Avondale identified as Polish, and the neighborhood remained predominantly Polish through the 1980s. Today, over half of Avondale identifies as Hispanic or Latine, with traces of its Polish Village community still present, though recent gentrification is once again shifting the neighborhood.

A crowd of people line the street to see Polish president Lech Wałęsa as he attends Palm Sunday Mass at St. Hyacinth Basilica, Chicago, March 24, 1991. Two people hold signs that welcome him and say “Solidarność,” which means “Solidarity” in Polish. ST-19041696-0190, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

The Polish Avondale “heyday” of the 1980s and 1990s aligned with the Solidarity Movement in Poland, and Polish migrants to Chicago of this period included a number of political refugees escaping Communist rule. St. Hyacinth’s was a hub for Solidarity-era activity. In 1991, a large crowd of Polish Americans welcomed Solidarity leader and then-newly elected President of Poland Lech Wałęsa to St. Hyacinth’s for Palm Sunday Mass.

Lech Wałęsa (holding palm fronds and flowers) and his wife, Danuta, at Palm Sunday Mass at St. Hyacinth Basilica, Chicago, March 24, 1991. ST-19041696-0181, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Lech Wałęsa (left foreground) genuflects during Palm Sunday Mass at St. Hyacinth Basilica, Chicago, March 24, 1991. ST-19041696-0158, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Solidarity initially referred to a trade union formed at the Lenin Shipyard in Gdansk, Poland, in 1980, which would go on to become the first independent trade union recognized by the state as part of the Warsaw Pact. As a leader of the Solidarity movement, Wałęsa was pivotal to ending Poland’s communist rule and became the first democratically elected president since 1926. He was president of Poland from 1990 to 1995.

Lech Wałęsa and his wife, Danuta, handle a wreath outside St. Hyacinth Basilica, Chicago, March 24, 1991. ST-19041696-0138, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

After the service, Wałęsa and his wife, Danuta, placed a wreath before a monument outside the church commemorating Fr. Jerzy Popiełuszko, a priest in Poland who was supportive of Solidarity and murdered by agents of Poland’s Security Service of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Rev. Popiełuszko was recognized as a martyr by the Catholic Church and exemplifies the role churches played in the resistance movement during the antireligious suppression of the Communist era.

Additional Resources

- Listen to CHM’s Peter T. Alter interview Lech Wałęsa in 2012

- See more images of Lech Wałęsa visiting St. Hyacinth Basilica in 1991

- Learn more about Chicago area’s vibrant Polish communities from the mid-1800s to today in our exhibition Back Home: Polish Chicago (May 20, 2023–June 8, 2024)

For St. Patrick’s Day, CHM curator of religion and community history Rebekah Coffman looks at Old St. Patrick’s Church as a monument to Chicago’s longstanding Irish community presence and how its stained glass windows reflect Irish American identity.

Old St. Patrick’s Church, also known as St. Patrick’s Roman Catholic Church, 2024. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman

St. Patrick’s Day in Chicago means the city is filled with Irish heritage on display. While Chicago may be best known for its green river, festive parades, and raucous pub crawls, Old St. Patrick’s Church in the West Loop neighborhood is a monument to Chicago’s longstanding Irish community presence.

Old St. Patrick’s Church, August 4, 1975. ST-19042225-0002, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Named for the patron paint of Ireland, Old St. Patrick’s Church was founded on Easter 1846 by Irish bishop William Quarter as the first English-speaking Catholic church in Chicago. Initially in a humbler wooden building at the intersection of Randolph and Desplaines Streets, the cornerstone was laid for a new brick building on May 23, 1853. Completed in 1856, the church would be one of a handful of buildings to survive the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, making it the oldest public building in Chicago today.

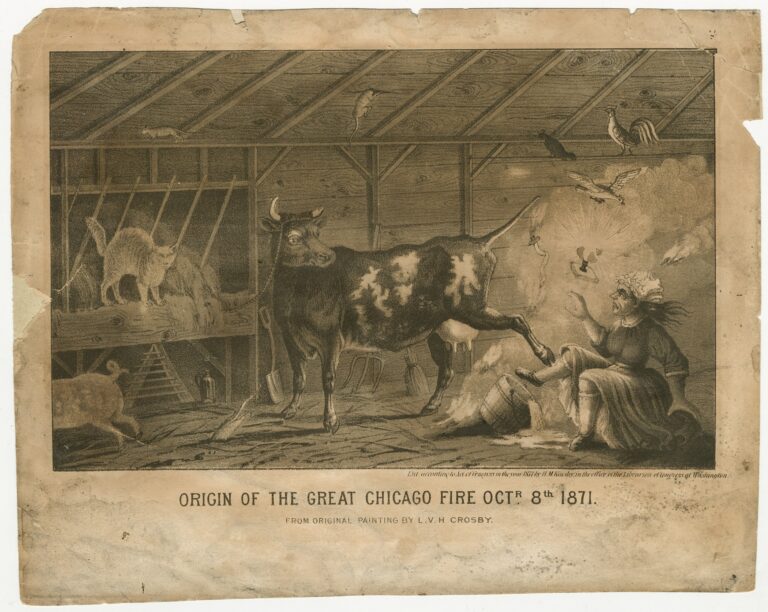

Cartoon by L. V. H. Crosby depicting “the Origin of the Great Chicago Fire” featuring a stereotyped image of Catherine O’Leary and her cow in a barn. CHM, ICHi-002945

Irish immigration to Chicago began in the 1830s and grew exponentially following serial potato crop failures beginning in 1845. By 1860, Chicago had the fourth largest Irish community in the country. Religious divides present in Ireland found their way to the Irish immigrants’ new home, with Protestants separating themselves from Catholics by both religious identity and social and economic class. Soon, Irishness in Chicago became publicly synonymous with Catholic and working-class or poor. Prejudice against Irish immigrants led to pervasive social stereotyping during this time, including the legendary story of Mrs. O’Leary and her cow as the source of the Great Chicago Fire.

View of the Irish Village at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition with a banner reading “Cead Mile Failte” meaning “Welcome.” CHM, ICHi-022941

Two decades later, Irish presence and identity were again on display as part of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. Two idealized Irish villages were included in the ethnographic displays along the Midway Plaisance, where visitors could see glimpses of the romanticized “everyday life” of the rural Irish. The setting included thatched cottages, a reproduced Muckrass Abbey, a recreation of Blarney Castle (complete with a place to kiss a piece of the Blarney Stone), and various cultural displays, including Celtic arts and crafts. This and other romanticized visions of an Irish homeland would go on to influence artists and designers looking for inspiration amidst the chaotic progress of the Industrial Revolution, including a young man by the name of Thomas O’Shaughnessy. He would become a cornerstone in defining Chicago’s flavor of the Celtic Revival Style.

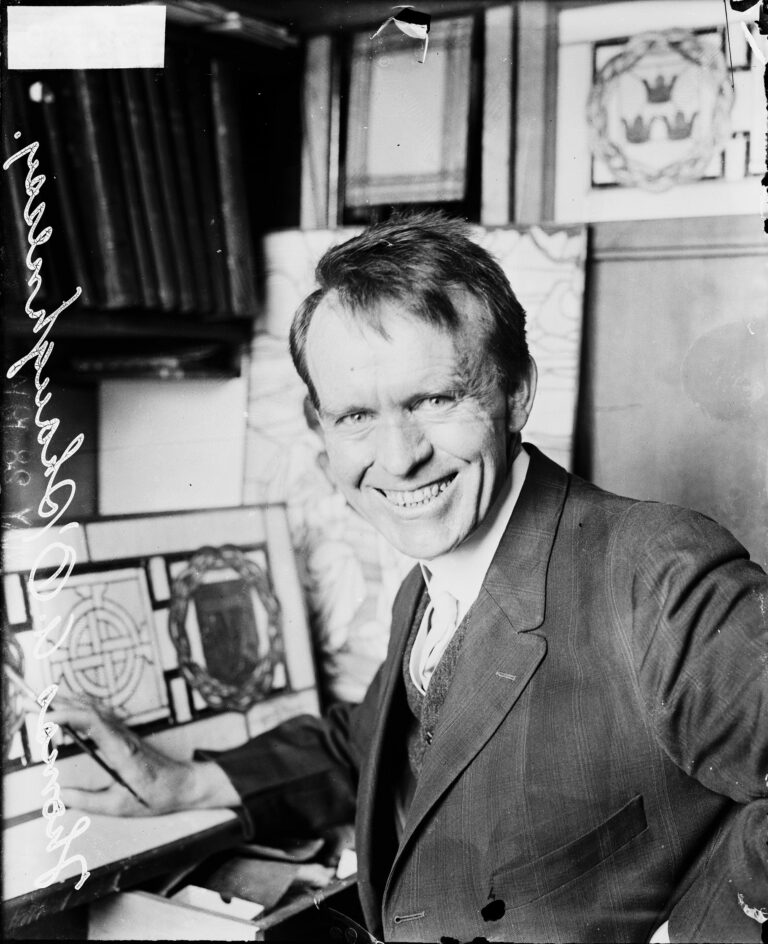

Artist Thomas O’Shaughnessy with a stained-glass tile featuring a Celtic design, May 16, 1914. DN-0062780, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

Born in 1870 and originally from Missouri, O’Shaughnessy studied stained glass at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, learning from local stained glass legend Louis Millet. Millet is perhaps best known for designing nature-inspired windows for buildings such as Louis Sullivan’s Auditorium Building and, with partner George Healy, the dome in the Grand Army of the Republic Hall at what is now the Chicago Cultural Center. O’Shaughnessy would later take the techniques he learned and apply them to a new visual language steeped in Irish heritage.

Artist Thomas O’Shaughnessy working on a piece of stained glass art, 1920. DN-0072728, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

As noted above, O’Shaughnessy became deeply inspired by Celtic design, first encountering it at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. In 1905–6, after he finished his formal studies and started work as an illustrator for the Chicago Daily News, O’Shaughnessy traveled in Europe to gain wider artistic inspiration.

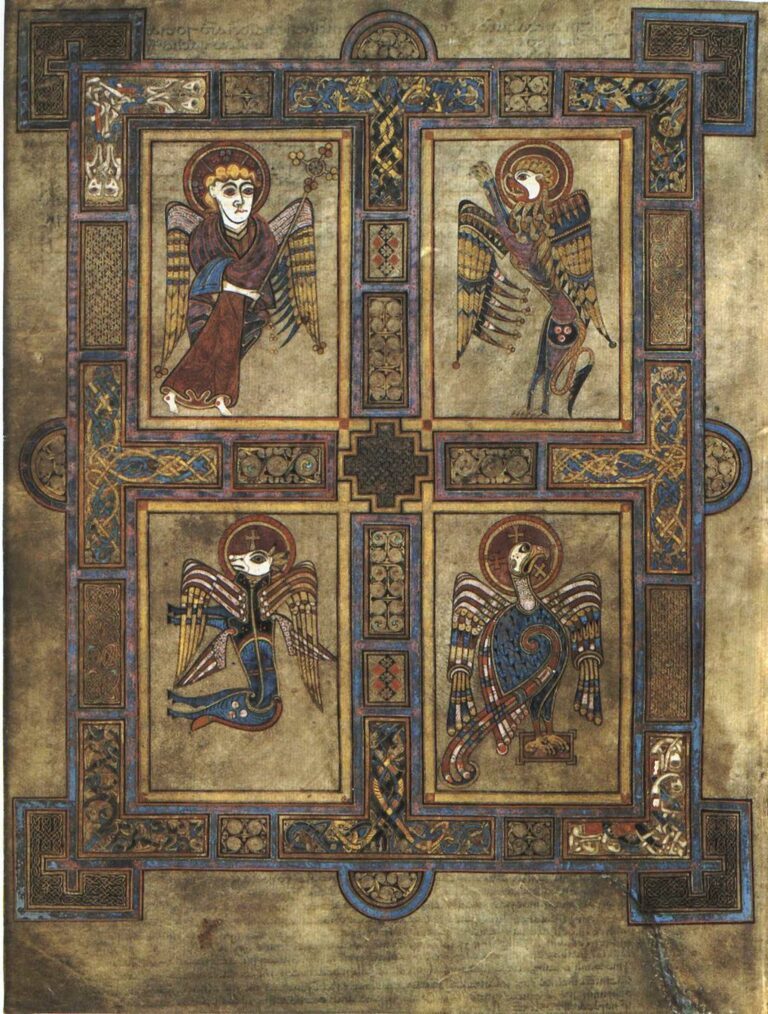

Pages from the Book of Kells, 9th century, Trinity College Dublin.

While in Ireland, he was particularly drawn to the themes and pattern work he saw in the Book of Kells, a 9th-century illuminated manuscript containing the four books of the Christian gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John). The Book of Kells is widely known for its impressive ornamentation and pages of illustration that infuse Celtic imagery and design with the Latin text of Christian scripture. These designs became a major source of inspiration for many artists during the late-19th and early 20th centuries as part of the Celtic Revival, and Celtic designs were documented, replicated, and incorporated in a number of fine and decorative arts.

Stained glass windows at the balcony of St. Patrick’s Church, 2024. Photographs by Rebekah Coffman

O’Shaughnessy brought this influence into his design work for St. Patrick’s Church, creating a distinctive hybrid Irish-meets-American style. He designed and installed fifteen major windows from 1912 to 1922, each incorporating Celtic elements to visually assert Irish American identity through the building’s decoration. Irish-born Chicagoans were at a near-peak in the city until quickly tapering after the Immigration Act of 1924.

St. Patrick’s Day Parade on State Street, Chicago, March 17, 1976. ST-15003202-0105 and ST-15003202-0107, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Irish immigration to Chicago was halted almost completely during the Great Depression until the 1950s, with a final big wave arriving after leaving during Irish unrest of the 1970s–90s. Today, more than 430,000 people in Cook County claim Irish ancestry and organizations like the Irish American Heritage Center in Irving Park continue to share and celebrate Irish presence in the city. While a number of formerly Irish parishes have shifted in use or been lost to demolition, Old St. Patrick’s stands today as a reminder of long-standing community presence.

Further Reading

- “Irish” in the Encyclopedia of Chicago

- St. Patrick’s Church History

- “Goose Island’s Earliest Residents: The Irish of Kilgubbin” in Chicago History magazine

A dynamic experience that will transport visitors back to a pivotal time in Chicago and US history and connect to the present.

CHICAGO (March 14, 2024) – The Chicago History Museum is thrilled to announce its upcoming exhibition, “Designing for Change: Chicago Protest Art of the 1960s–70s.” Set to open on Saturday, May 18, 2024, this exhibition is a dynamic experience that will transport visitors back to a pivotal time in Chicago and US history and connect that era to issues of the present. Through the lens of protest art, visitors will gain a deeper understanding of one of the most tumultuous periods in US history, how it continues to shape our world today, and the role that art played in effecting change.

The exhibition features more than 100 thought-provoking artifacts, including posters, fliers, signs, banners, newspapers, magazines and books from the 1960s and ’70s. These expressive works convey the often-radical ideas regarding race, war, gender equality and sexuality that challenged the social norms of the time. The exhibition also features period photography and first-person interviews delving deeper into Chicago’s tradition of activist art, now called “artivism.” A concluding section features works by a new generation of artivists who are carrying on Chicago’s rich legacy of protest art in response to critical issues of our time.

When asked about the significance of the exhibition, curator Olivia Mahoney said, “Chicago artists helped change the world by creating powerful signs, symbols, and imagery for the Civil Rights, Black Power, anti-Vietnam War, women’s liberation and early LGBTQIA+ movements. We hope the exhibition will remind visitors of the critical role that free expression plays in a democratic society, and that it will inspire them to become more involved in civic affairs and work for positive change.”

The Chicago History Museum invites the public to join them in exploring the profound impact of protest art and its ability to shape society. Don’t miss this opportunity to witness the transformative power of design and be inspired to create positive change.

A preview week for “Designing for Change” will be held May 13–17, during which members of the press are invited to view the exhibition and engage with the powerful narratives it presents. For more information, please visit the Chicago History Museum’s website or contact the Museum’s press office.

Media kit available here: https://app.box.com/s/supm186ynm62k12js889jqtpi1ibkkwz

###

For National Jewel Day, CHM costume collection manager Jessica Pushor shares a bit about the jewelry in our Costume and Textiles Collection and highlights the variety of our holdings.

The costume collection of the Chicago History Museum comprises an estimated 50,000 objects related to the fashion and clothing history of Chicago. Within this astounding collection of fashion history are an estimated 2,000 pieces of jewelry and watches. Some of these pieces were made in the city by skilled jewelers and craftspeople, while others came from far off locations, brought back as gifts or passed down through generations of families before being donated to the collection. The pieces in the jewelry collection are of vastly different materials and styles that reflect the changing fashions of peoples across the past two hundred plus years.

Parure, 1855. Pearls, silver. Maker unknown. Gift of Mrs. William H. Hazlett. 1992.246a-f. ICHi-55020

This parure includes earrings, a necklace, and a brooch, all in its original brown leather presentation case lined with red velvet. It belonged to the donor’s maternal grandmother, Elizabeth Jane Swetting, who received it as a wedding gift from her husband Joseph E. Gary, the judge who presided over the Haymarket trial in 1886.

Mourning necklace and pendant locket, c. 1865. Tortoiseshell. United States. Gift of Mrs. Mason Bross. 227-3H. ICHi-170008

This Victorian-era mourning necklace features a large, oval-shaped locket hung from a large carved chain. On the locket is a high-relief monogram “H. F. H.” carved in scrolling script, which is encircled by a carved ouroboros, a motif of a snake eating its own tail, a symbol of life and death in Victorian jewelry.

The donor, Mrs. Mason Bross (née Isabel F. Adams), was the daughter of George E. Adams, a Chicago lawyer and Illinois congressman. Her husband, Mason Bross, was also a Chicago lawyer, and they had one son, John Bross.

Parure with necklace, bracelet, pair of pendant earrings, brooch, and bracelet, c. 1870. Coral, gold. Gift of Mrs. William S. Jenks. 1938.121. ICHi-074304, ICHi-074300

Coral has long been a popular material due to its amuletic associations and therapeutic properties, but it first gained popularity as a fashionable material between 1660 and 1798. Coral use in jewelry continued to fall in and out of fashion throughout the Victorian era.

This set, featuring bacchantes and amphorae-shaped pendants and drops, was likely made in Italy by the firm Francesco De Simone & Figlio. The company, founded in 1855, is based in the renowned Spanish Quarters of Torre del Greco, the heart of coral jewelry near Naples. Torre del Greco has been renowned since the 17th century for being a major producer of coral jewelry and cameo brooches.

The set belonged to Mrs. Edwin L. Gillette, mother of the donor, who came to Chicago in 1859.

Cuff links, c. 1880. Gold. Tiffany & Co., United States. Gift of Mr. Robert Allerton. 2053-7H. ICHi-170003

With the signing of the Treaty of Kanagawa in 1854, Japan opened trade to the United States, which began the flow of Japanese ornamentation and motifs into Western design. Tiffany & Co., an early adopter of Japanese style, was successful at combining Japanese themes and techniques while using materials that appealed to Western consumers.

These cufflinks were donated to the Museum by Robert Henry Allerton (1873–1964), son and heir of First National Bank of Chicago cofounder Samuel Allerton. Robert was a philanthropist who served as a trustee and honorary president for the Art Institute of Chicago.

Pocket watch and chain, 1860–1900. Gold, enamel, and diamonds. Patek, Philippe & Co., Switzerland. Gift of McCormick Estates. 1957.1008. ICHi-170007

This women’s pocket watch and chain has a dark blue enamel case set with diamonds, a white porcelain face with black Roman numerals and hands, and two blue enamel pins set with diamonds and pearls.

Patek Philippe is a luxury watch manufacturer established in 1839 in Geneva, Switzerland, as Patek, Czapek & Cie by Antoine Norbert de Patek and François Czapek. Adrien Philippe, a French watchmaker who invented the keyless winding mechanism, joined the company in 1845. In 1851, the company name officially changed to Patek, Philippe & Cie.

Necklace, c. 1900. Diamond, platinum. Maker unknown. Gift of Gordon Palmer. 1980.56a. ICHi-073850

While Bertha Palmer’s clothing dazzled in their own right, her jewel-encrusted accessories completed many ensembles. Mrs. Palmer received two diamond chokers, or dog collars, for the 1900 Paris Exposition; this one holds 1,236 diamonds. The Museum received this necklace into its collection with a broken clasp. As the clasp usually contains the engraving of a manufacturer’s mark, we unfortunately have no way of identifying the maker.

Pendant, c. 1905. Gold, opal. A. Fogliata, United States. Gift of Mrs. Charles Batchelder. 1977.87.2 . ICHi-177697

At the center of this gold pendant is a gold bower of leaves set with tiny round opals surrounding a repoussé figure of a nymph with flowing hair playing a lute. Three opals are suspended from the bottom of the pendant with fine gold chains.

Annibale Fogliata was an Italian-born jeweler and metalsmith who came to Chicago in 1904 to teach metalworking at Hull-House. He eventually left Chicago in 1907 for NYC.

Necklace, c. 1910. Gold and yellow topaz. Frances Macbeth Glessner, Chicago (United States). Gift of Mrs. Charles F. Batchelder. 1977.87.1. ICHi-69798

The maker of this necklace, Frances Macbeth Glessner, was an admirer of Fogliata’s work, purchasing pieces from him as gifts and to wear herself and even taking silversmithing lessons with him in 1905. This piece, comprising gold chains and yellow topaz stones, was designed and created by Glessner as a gift for her sister Anna Macbeth Robertson.

Left: Necklace, c. 1915. Horn and celluloid. Georges Pierre, France. Gift of Miss Neva Douglas. 1976.81.2. ICHi-085061. Right: Necklace, c. 1915. Horn, glass, silk. Elizabeth Bonte, France. Gift of Miss Neva Douglas. 1976.81.1. ICHi-085057

These two Art Nouveau necklaces are similar in that they both have a carved horn pendant with beads on the sides. The one on the left is by Georges Pierre, whose work can be identified by his initials “G.I.P.,” and the one on the right is by Elizabeth Bonte, who studied at the École nationale supérieure des Arts Décoratifs in Paris and was one of the few women jewelers during that time. Once competitors, Bonte and Pierre merged their workshops and worked together until 1936.

Parure, c. 1960. Silver, rhinestones, glass beads. Trifari, United States. Mrs. Charles Chaplin, 1976.241.148a-c. ICHi-74288.

This parure is made of silver metal with rhinestones and blue and yellow glass beads in the shape of flowers and leaves. Trifari was founded in the 1910s by Gustavo Trifari, an Italian immigrant and son of a Neapolitan goldsmith. The success of Trifari, and the reason for its collectability today, is most often credited to French designer Alfred Philippe, the company’s chief designer from 1930 until 1968. His use of invisible settings for stones, which he originally developed for Van Cleef & Arpels, added a level of craftsmanship and technique that had not been previously seen in costume jewelry.

“Shandelier” earrings, c. 1950. Metal, beads, string. Jano Walley, Chicago (United States). Gift of Mrs. Jano Walley. 1985.708.27a-b. ICHi-066576

These earrings represent the idea of “total design” promoted by Chicago’s Institute of Design. They were made by artist Jano Walley when she was a student there. A loop of string is attached at center apparently intended to loop over the ear. After finishing her studies, Walley became an artist and taught jewelry and ceramics at various Midwest art institutions, including Black Mountain College and the University of Illinois at Navy Pier (now University of Illinois Chicago). Both Jano and her husband, John Walley, were major contributors to the Chicago arts scene in the 1940s–50s and often held arts-related events at their studio and apartment.

Necklace, c. 1975. Silver and amber. Robert Mucklow, Chicago (United States). Gift of Robert Staples and Barbara Fahs Charles. 2013.97.1. ICHi-073636

The maker of this necklace, Robert Mucklow (b. 1952) was born in Chicago and worked as a janitor and later as a polisher in a wedding ring factory before pursuing a metalsmith career. During the 1970s, he operated a studio in south suburban Park Forest and won several awards at local art fairs with his unique pieces of jewelry that incorporated organic materials, especially amber and ivory, using traditional metalsmithing techniques.

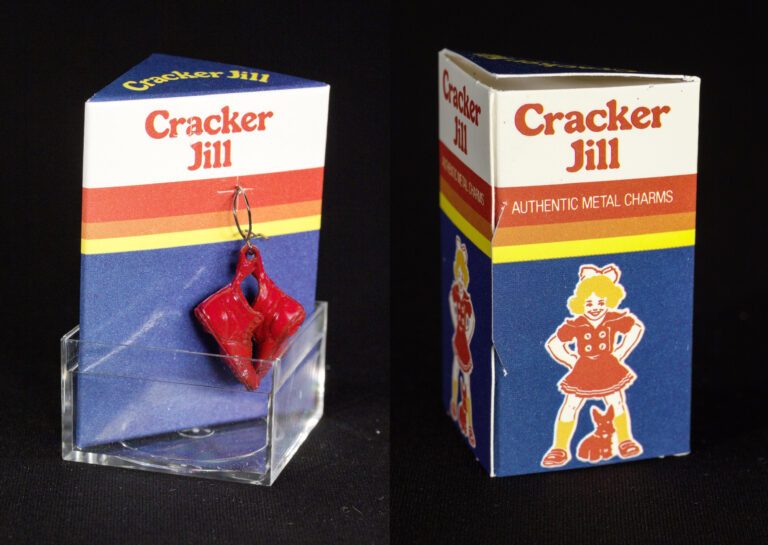

Cracker Jill earrings, c. 1982. Tin. SS/F Designs, Chicago (United States). Gift of Peggy Shure and Lynn Foster. 1983.33.2a-b. Left: ICHi-170771, right: ICHi-170774.

SS/F, Inc. was a jewelry firm founded in 1976 by Peggy Shure and Lynn Foster. The Cracker Jill line was created when Shure discovered barrels of metal Cracker Jack toys and their original molds when visiting her husband’s family business, the Tootsietoy Factory of Chicago. The Tootsietoy Factory created the original metal toys used as Cracker Jack toy prizes from 1894 to 1942 but replaced them with paper and plastic toys during World War II.

The Cracker Jill logo was created by Mike Gournoe, a packaging designer and neighbor of Shure, and was based on the “Little Orphan Annie” character. The charms were painted in nontoxic colors and strung on black twill cord for necklaces or from small hooks for earrings. These earrings retailed for $3 in 1982.

Bracelet, c. 1987. Bamboo, black lacquer, quartz crystal stones. Tina Chow, United States. Gift of Sheila Dunteman. 2017.14.1. ICHi-170844

Tina Chow (1950–92) was a model, muse, and much more—she was also a restauranteur, sculptor, and jewelry designer. Born Bettina Louise Lutz in Ohio to a German American father and Japanese mother, her family moved to Japan in the 1960s, where she began her modeling career. In the 1970s, she married Michael Chow, founder of the Mr. Chow restaurant chain. In the mid-to-late 1980s, Chow began to experiment with the healing properties of crystals and holistic medicine. Her most famous design, the ‘Kyoto’ bracelet, was created around the time Chow was diagnosed with HIV. The design was created in collaboration with the Japanese master bamboo craftsman, Kosuge Shochikudo. Enclosed in the bamboo design are seven rose quartz crystals known for their healing properties. This bracelet was purchased in the early 1990s at the avant-garde Chicago clothing store Ultimo at 114 East Oak Street, which was run by Joan Weinstein (1935–2009). Chow died at age 41 due to complications from AIDS.

In 2024, the holy month of Ramadan began for many Muslims at sundown on Sunday, March 10. CHM curator of religion and community history Rebekah Coffman talks about the significance of iftar, an important part of Ramadan.

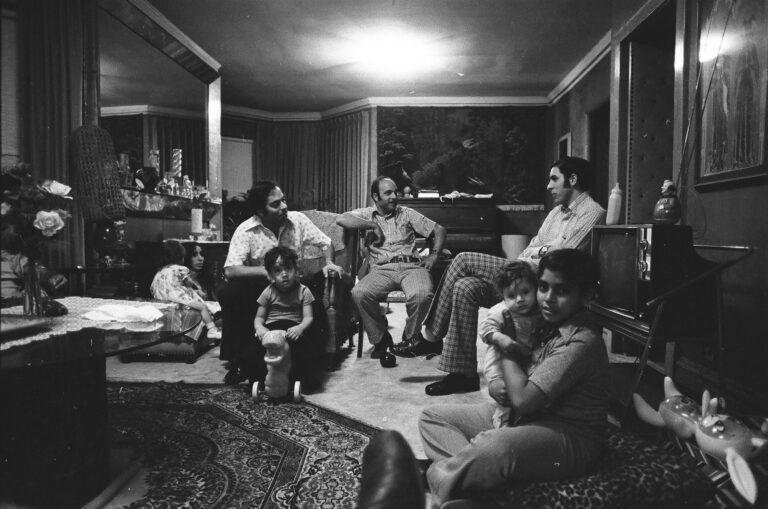

Friends and family gather for iftar, September 28, 1974. ST-10104872-0014, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

The Islamic month of Ramadan is a time of prayer, fasting, and personal and community reflection. The ninth and holiest month of the Hijri, it is a time when Muslims around the world will fast daily from sunrise to sunset, fulfilling one of the five central tenets of Islam in commemoration of the Quran’s revelation to Muhammed.

The kids’ table at iftar, September 28, 1974. ST-10104872-0027, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Each evening, after Magrib (evening prayer), communities and families come together for iftar, a meal to break the day’s fast. This includes preparing and eating delicious foods and desserts and is also a time for music, telling stories, playing games, and spending time in each other’s company, passing traditions down through generations. These communal moments were recognized in 2023 as globally significant Intangible Cultural Heritage by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), noting how vitally important sharing rituals like iftar can be to maintaining and preserving cultural traditions.

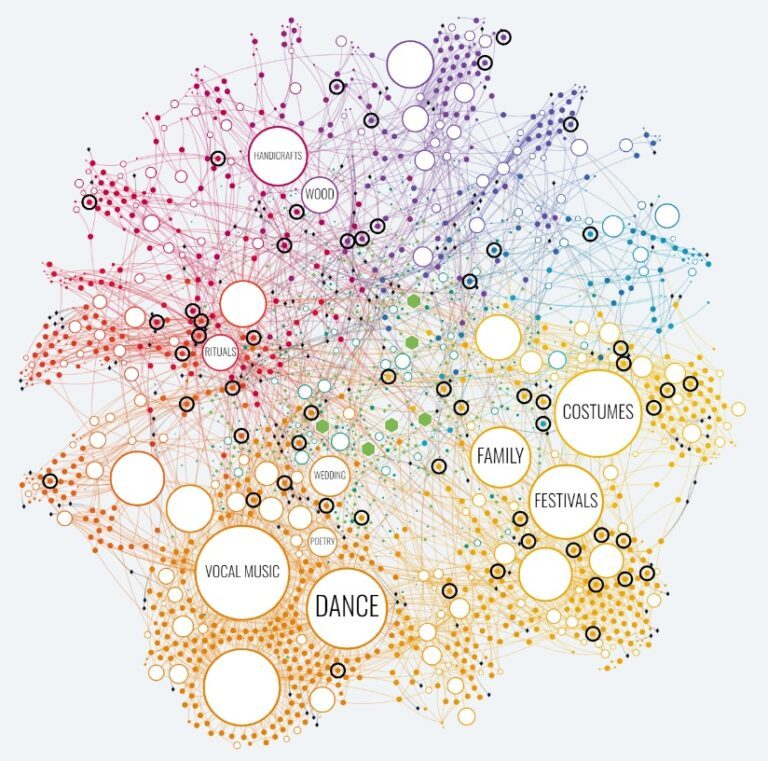

Screenshot of UNESCO’s interactive constellation map of different types of intangible cultural heritage, 2024.

Intangible heritage refers to living traditions beyond monuments and collections and is embodied through oral traditions, rituals, festive events, social practices, and knowledge. It is heritage expressed through living action that bridges the past with the present, and in religious contexts is also known as “living religious heritage.” Many examples of rituals and foods are recognized and celebrated as intangible heritage today, with more being added to our shared global heritage. UNESCO does not currently include the United States in its official lists for recognized intangible heritage, but traditions and rituals remain transnational ways of keeping intangible heritage alive among communities.

Friends and family at iftar, September 28, 1974. ST-10104872-0005, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

A local example of these intangible moments was captured in a series of photographs for the Chicago Sun-Times in 1974. Religion reporter Roy Larson wrote about his experience attending an iftar at the home of Chicagoans Donna and Abraham Mohammed. Joined by family and friends, including the Abu-Shalbacks, the mealtime discussion centered on Palestinian heritage and what the idea of “home” means to them. Larson describes the beautiful meal that was shared, including maqluba, a traditional Arab/Palestinian dish of meat, rice, and vegetables that is cooked and then flipped onto a dish when served. In the spirit of sharing, the Abu-Shalbacks’ then-twelve-year-old son, Sami, invited Larson to his class at 55th Street and Fairfield Avenue in Gage Park to study Arabic and the Quran.

Family and friends sharing an iftar meal, September 28, 1974. ST-10104872-0012, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

In the 1970s, there were approximately 25,000–35,000 Muslims in Chicago. Chicago’s burgeoning Palestinian diaspora was then centered in the Gage Park and Chicago Lawn neighborhoods on the Southwest Side. Today, there are 350,000 Muslims in Illinois, most living in the Chicagoland area, making it the highest concentration of Muslims in the country. The Palestinian diaspora is a vital part of the community, with more Palestinians living in Cook County than elsewhere in the United States. Suburban areas such as Oak Lawn, Orland Park, and Bridgeview have become the heart of Chicagoland’s Palestinian community with the stretch of Harlem Street from 79th to 123rd earning the moniker “Little Palestine.”

Mosque Foundation in Bridgeview, Illinois, 2024. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman

The Prayer Center of Orland Park in Orland Park, Illinois, June 26, 2019. Photograph by Tim Paton. CHM, ICHi-175817

One of our previous exhibitions, American Medina: Stories of Muslim Chicago (October 21, 2019–May 16, 2021), preserved and shared a wide range of Muslim voices, perspectives, and traditions, demonstrating the diverse Muslim communities that call Chicago home today. This includes more than 140 oral histories, many of which are available to listen to through SoundCloud and research via our online database, including memories of Ramadan and perspectives from other Palestinian Chicagoans.

Additional Resources

- Read the Encyclopedia of Chicago entry on Muslims

- Read the Encyclopedia of Chicago entry on Palestinians

- Peruse the Muslim Oral History Project interviews on ContentDM

- Listen to interviews from American Medina: Stories of Muslim Chicago on SoundCloud

February 2024 marks 110 years since the start of a labor action commonly known as the Henrici’s restaurant waitress strike. In this blog post, CHM editor and content manager Heidi Samuelson recounts the strike, its history, and its effects.

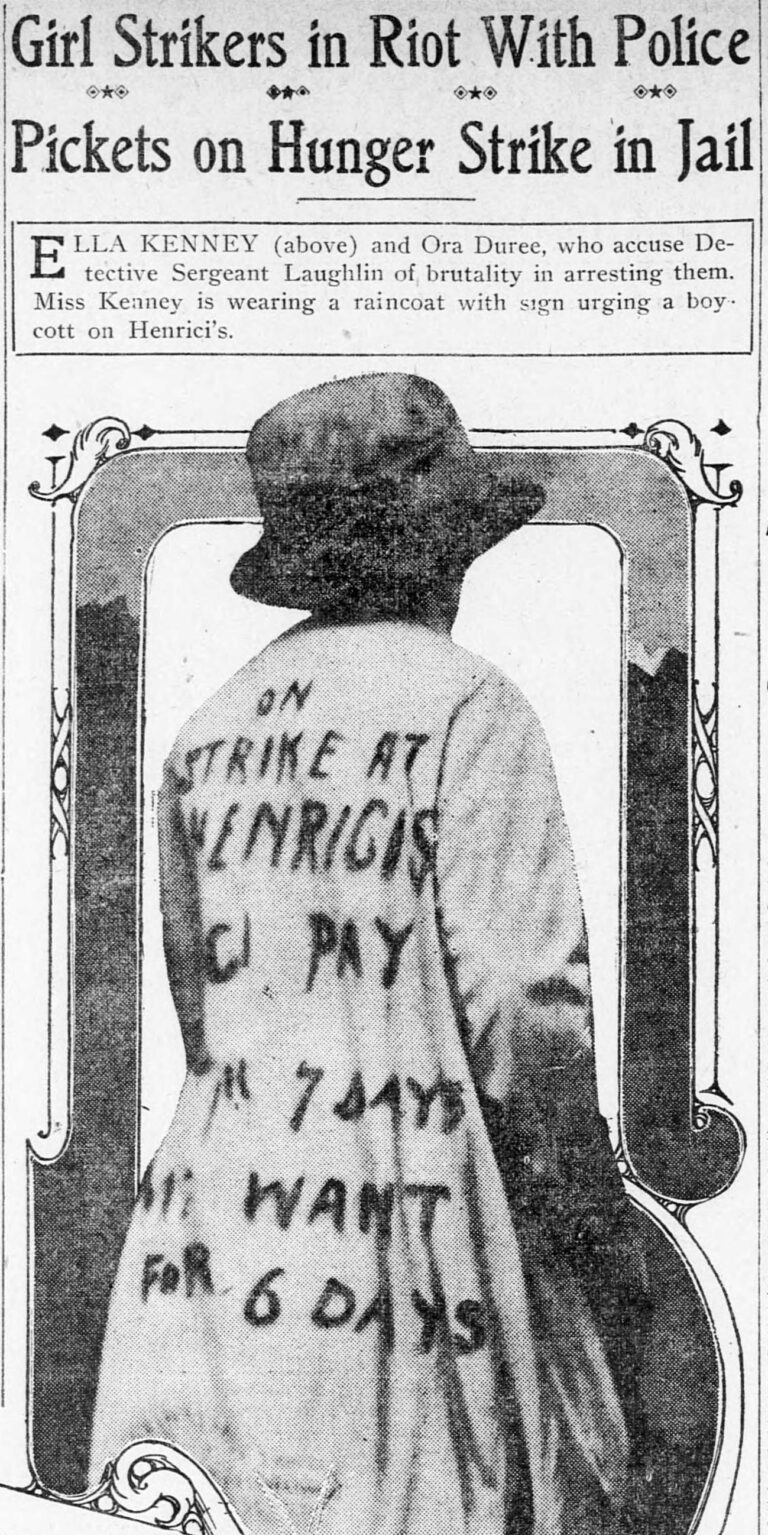

“Girl Strikers in Riot with Police,” Chicago Examiner, February 10, 1914

In February 1914, four waitresses marched through a lunchtime crowd outside Henrici’s restaurant at 67 West Randolph Street wearing coats painted with their demands: “On strike on at Henrici’s. Henrici’s pay $7 for 7 days. We want $8 for 6 days.” When police tried to arrest them, the “girl strikers” sat down and refused to go without a fight. They were later charged with encouraging an illegal boycott.

The waitresses were members of Chicago Waitresses Union Local 484 who, along with the Chicago Cooks Union 864, organized a strike to demand recognition of the waitresses’ union, a living wage, and better working conditions. Henrici’s was selected as the first target of their picketing, after owners had promised to fire any waitresses who joined the union. The restaurant manager at Henrici’s told reporters their waitresses were asked but “unwilling” to join the union.

Mabel Burke, a union member, being arrested for conspiracy and illegal picketing, February 1014; DN-0062302, Chicago Daily News Collection, CHM

For weeks, the sidewalk outside the restaurant was picketed by women encouraging patrons to boycott the establishment. The picketers were frequently arrested, as police often sided with businesses during workers’ strikes.

Ellen Gates Starr after being arrested for interfering with the waitress strike in front of Henrici’s restaurant, March 19, 1914; DN-0062287, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

Among those arrested was Ellen Gates Starr, cofounder of Hull-House and a member of the Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL), who had lent her support to the strikers. Starr noted in her essay “Efforts to Standardize Chicago Restaurants—The Henrici Strike” that although Illinois law permitted peaceful picketing, the police sometimes arrested the same woman twice in a day, and yet none of the strikers’ cases was ever tried.

The Chicago WTUL was founded in in 1904 and was one of the most active branches of the national organization, which aimed to organize women workers into trade unions, lobby for protective legislation and woman suffrage, and promote vocational education. The WTUL was a mix of middle-class and working-class women. By 1910, it had deepened its alliance with the Chicago Federation of Labor, promoted the leadership of working-class women, and played a key role in the 1910–11 garment workers’ strike—supporting striking workers and their families and helping draft the agreement to end the strike.

Front cover of pamphlet titled “The Eight Hour Fight in Illinois by The Girls Who Did the Work,” leaflet no. 4, published by the Chicago WTUL, 1909; CHM, ICHi-177353

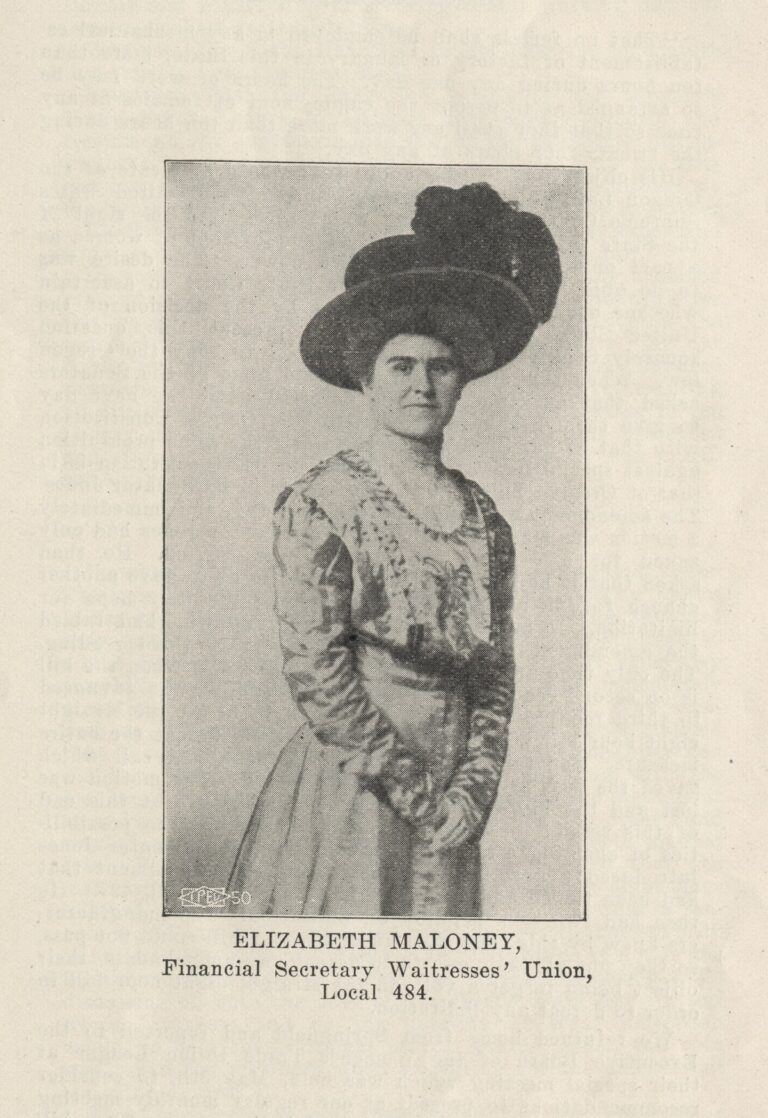

The 1914 waitresses’ strike expanded to twenty more restaurants that were all part of the Restaurant Keepers Association. Though it eventually collapsed due to a series of injunctions against the picketers, it gained significant press attention. Due to this attention, Elizabeth Maloney, a WTUL board member and one of the Waitresses Union Local 484 founders, testified before the Commission on Industrial Relations, or the Walsh Commission, created by US Congress in August 1912 to evaluate US labor law and working conditions.

Portrait of Elizabeth Maloney, financial secretary of the Waitresses Union Local 484, Chicago, c. 1909. CHM, ICHi-067690

During her testimony Maloney said:

“When you look at the profit side of the concern and look at the wage column, and see the wages as low as two or three or four dollars a week, and you know that industry is piling up millions of dollars at the expense of the girls, that side of the table should be equalized a little more, and I think a girl should be entitled to live decently and properly and enjoy some of the things in life that her employer wants his children to have.”

Additional Resources

- Learn more about women’s labor actions in “Underpaid, Undervalued,” part of our online experience Democracy Limited: Chicago Women and the Vote

- Find materials from the Women’s Trade Union League of Chicago in the Abakanowicz Research Center, which is always free to visit

To mark Saint Valentine’s Day, CHM reference librarian Maggie Cusick shares select valentines from our greeting card collection.

On February 15, 1872, the Chicago Tribune wrote: “Young maids and misses were yesterday anxiously hovering about the shops where valentines are sold, and bothering the postmen with inquiries after those that they thought they ought to get. Those who received were happy, and those who failed to receive lingered on in the faint hope that their tender missives must be lost in some corner of the Post Office, which would in due time give up its spoil.”

Chicagoans still looked forward to St. Valentine’s Day even just four months after the Great Chicago Fire.

Here at the Chicago History Museum, we have a collection of thousands of greeting cards from the 1840s to the 1990s that include cards for Christmas, birthdays, Easter, Mother’s Day, Father’s Day, Thanksgiving, New Year’s, and yes, valentines—13 boxes of them.

This collection is a composite of many donations over time organized by subject and type. They fall into our category of “Prints and Photographs” and therefore can be served out to researchers in the Abakanowicz Research Center (ARC).

The valentines in the collection showcase the range of stylistic trends over time, and include wonderful handmade and homemade examples, and instances of addressed ones where we can maybe learn a little about the sender and receiver. They can be fun for those who are interested in many areas including design history, the history of ephemera, the history of correspondence, the depiction of relationships over time or the history of courtship, printing history, or specific artists or producers—such as Esther Howland, from New England, the first manufacturer of valentines in the US starting in the 1850s or Aveline Thorpe, working here in Chicago in the early 1900s—to name just two!

If you’re so inclined, please visit the ARC and peruse the flurry of lace, ribbons, satin, silk, paper, and gold foil, professing love—or disdain.

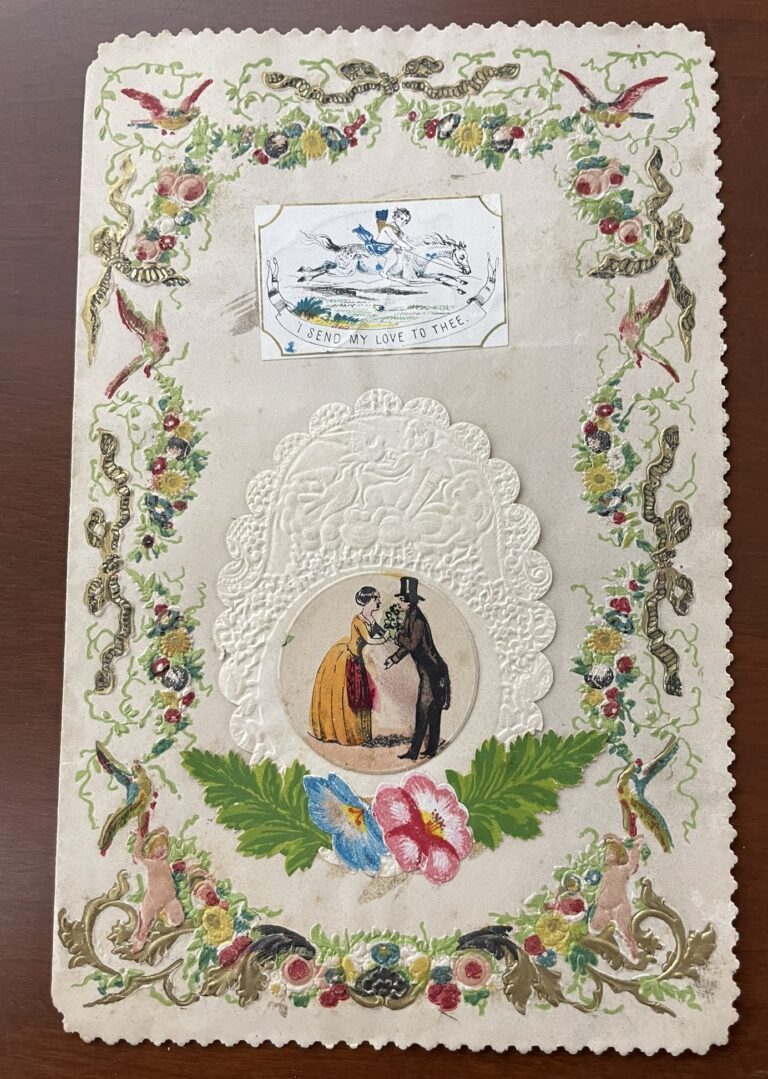

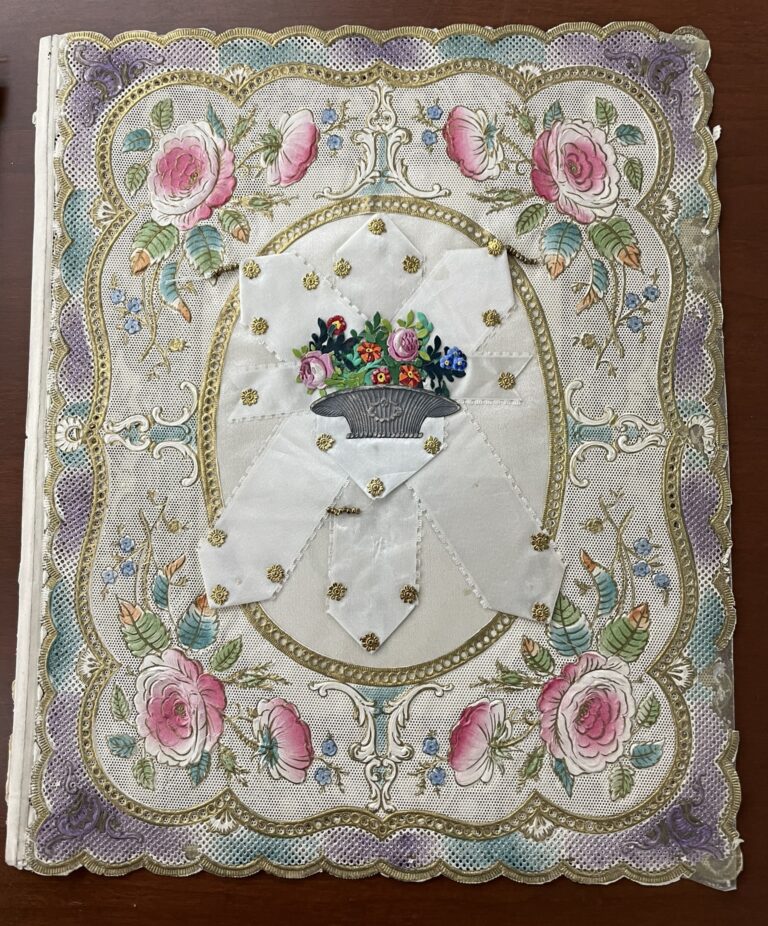

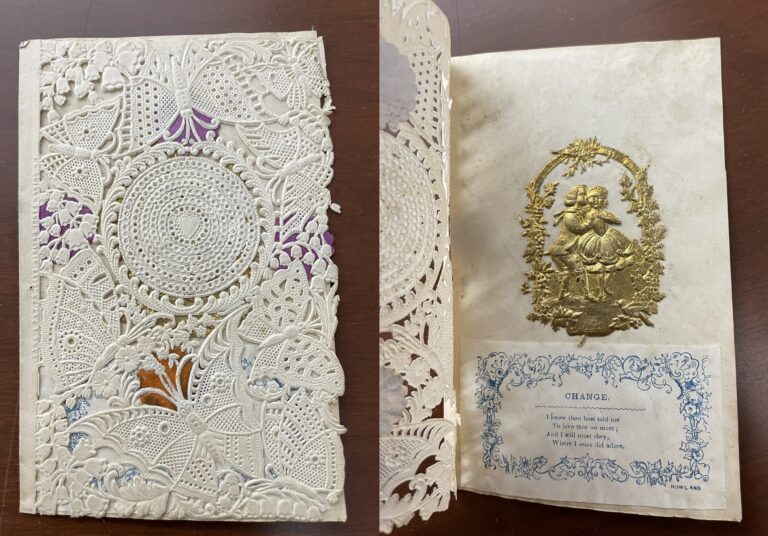

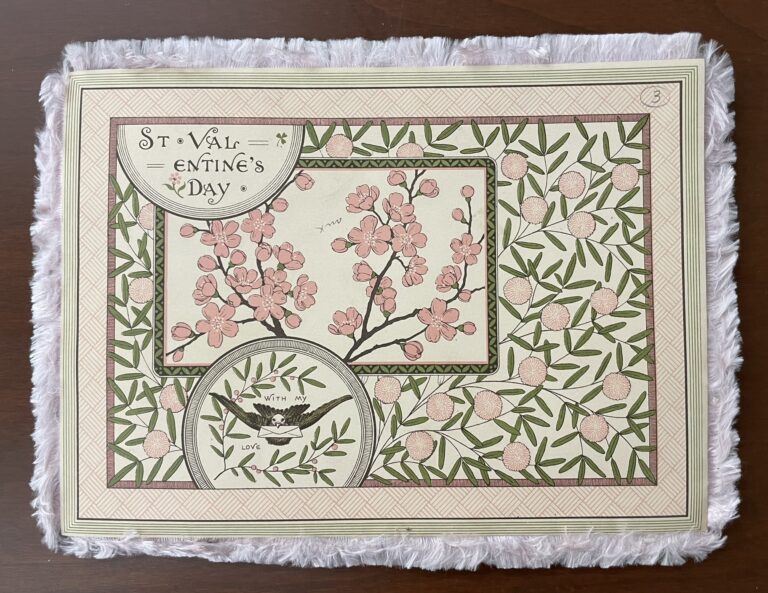

Early examples in the collection includes lacy and ornate cards from the mid 19th century that were typically found in bookshops and stationery stores such as Norris & Hyde, McNally, and E.L. Andrews. A Tribune reporter’s description said it was as if “engraver’s art had gone mad in the hands of some possessor” and “dainty and exquisite as if wrought by fairy fingers for fairy loves” (Chicago Tribune, February 15, 1859).

Esther Howland was the first manufacturer of valentines in the US, based out of Massachusetts. She began in the late 1840s after being inspired by an imported card. Her goal was to use embossed paper to look like lace. Above are two example of her work from our collection. Cards were being imported en masse to Chicago during that period—according to the Tribune, on January 14, 1859, “The largest stock of Valentines ever in Chicago is being received from New York by McNally & Co., 81 Dearborn street [sic]. Country dealers should by all means order from them, as by do doing they can be suited much better than by writing to New York.” This shipment possibly included some of Howland’s cards!

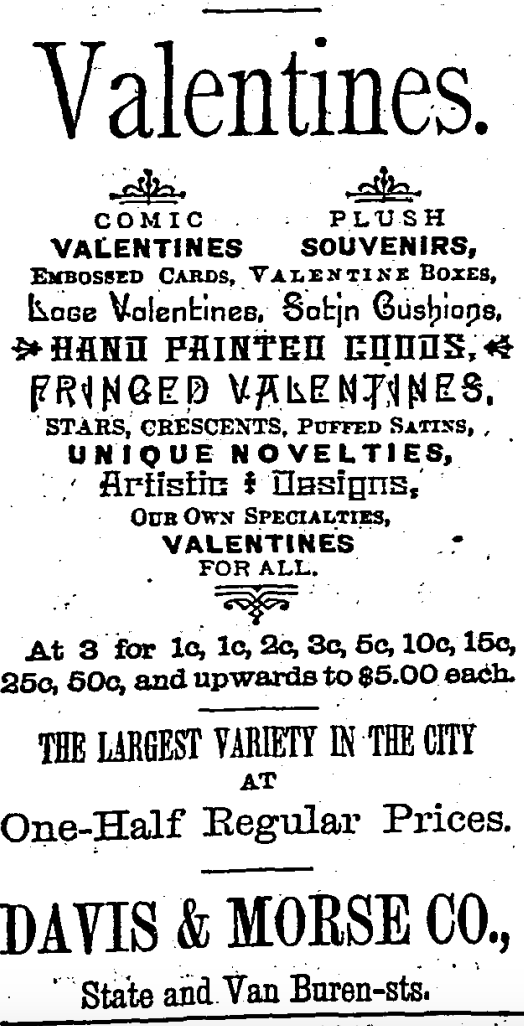

An advertisement for valentines in the Chicago Tribune, February 8, 1885.

In the 1880s, these “humorous and loving devices,” costing anywhere from 5¢ to $5, started to move away from the older style and saw a “card, large and small, modest in its adornment or elegant in its ornamentation,” and floral and landscape designs, pressed natural flowers, winter scenes, doves in a tree with verse, or fan shaped cards come into fashion. (Tribune, February 12, 1882)

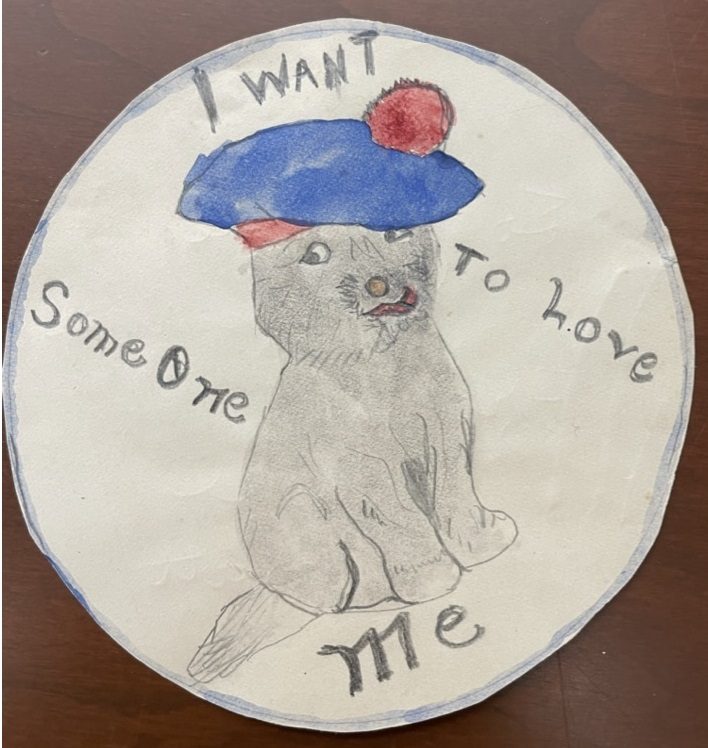

Before Esther Howland made valentines more affordable for Americans, in addition to importing them, many people made their own. We have some wonderful, whimsical examples of homemade cards in our collection.

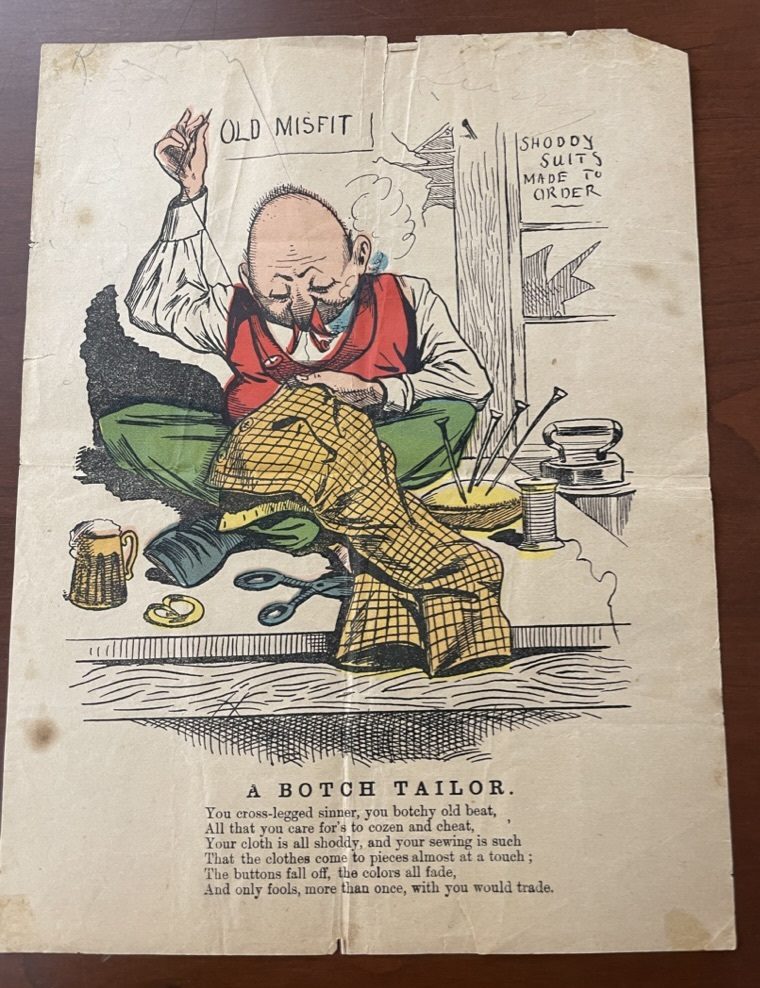

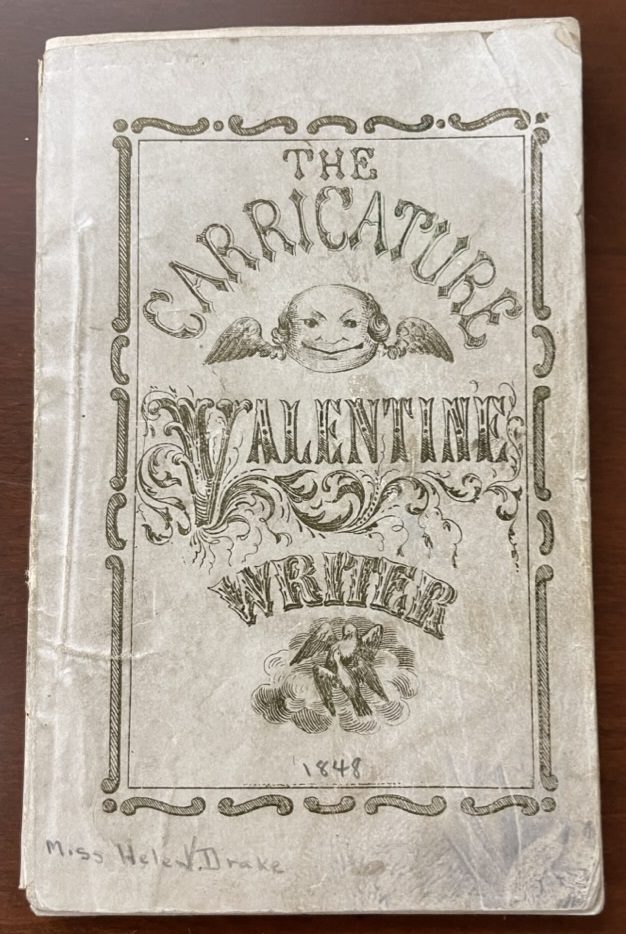

Common throughout this period was the “comic” valentine, sometimes known as the “penny dreadful” or a “vinegar valentine.” These were essentially mean cards, often with caricatures, that people would send to people they held a grudge or wanted to hurt—the original “trolling” perhaps! The Tribune wrote of a magazine illustrator named G. Howard who would create them when he was “out of humor and dissatisfied with life”! (Chicago Tribune, February 9, 1896).

Above is a vinegar valentine about a tailor from the late 1800s and then a guide to writing these, published in New York in 1848, that provides prewritten verse to address any number of sorts of people.

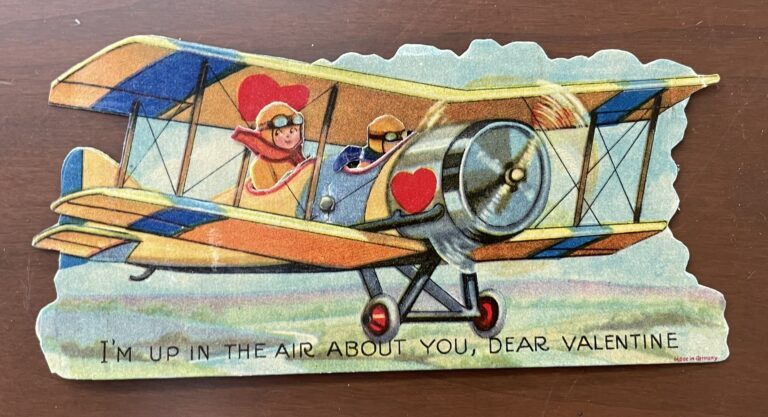

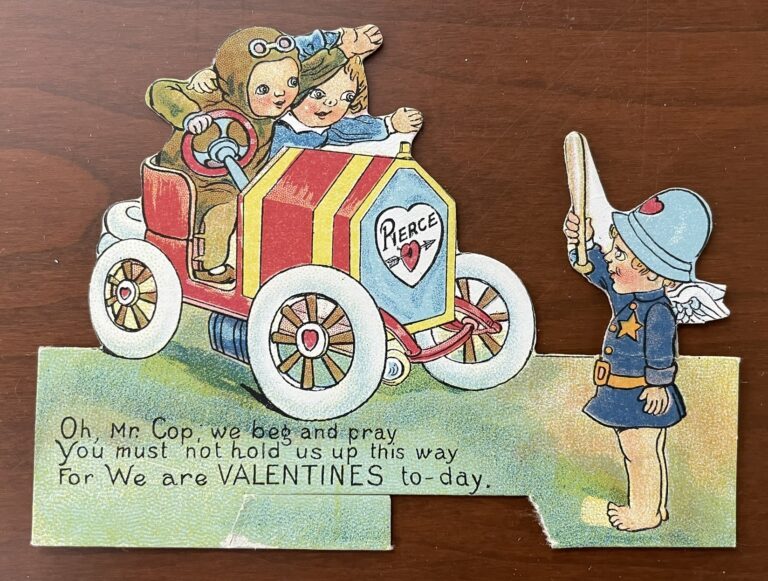

By the 1890s, the Tribune noted that bicycles, the “New Woman,” and other “modern” themes were appearing in valentine illustrations. How about motorcars, motorbikes, and airplanes? (Chicago Tribune, February 7, 1897)

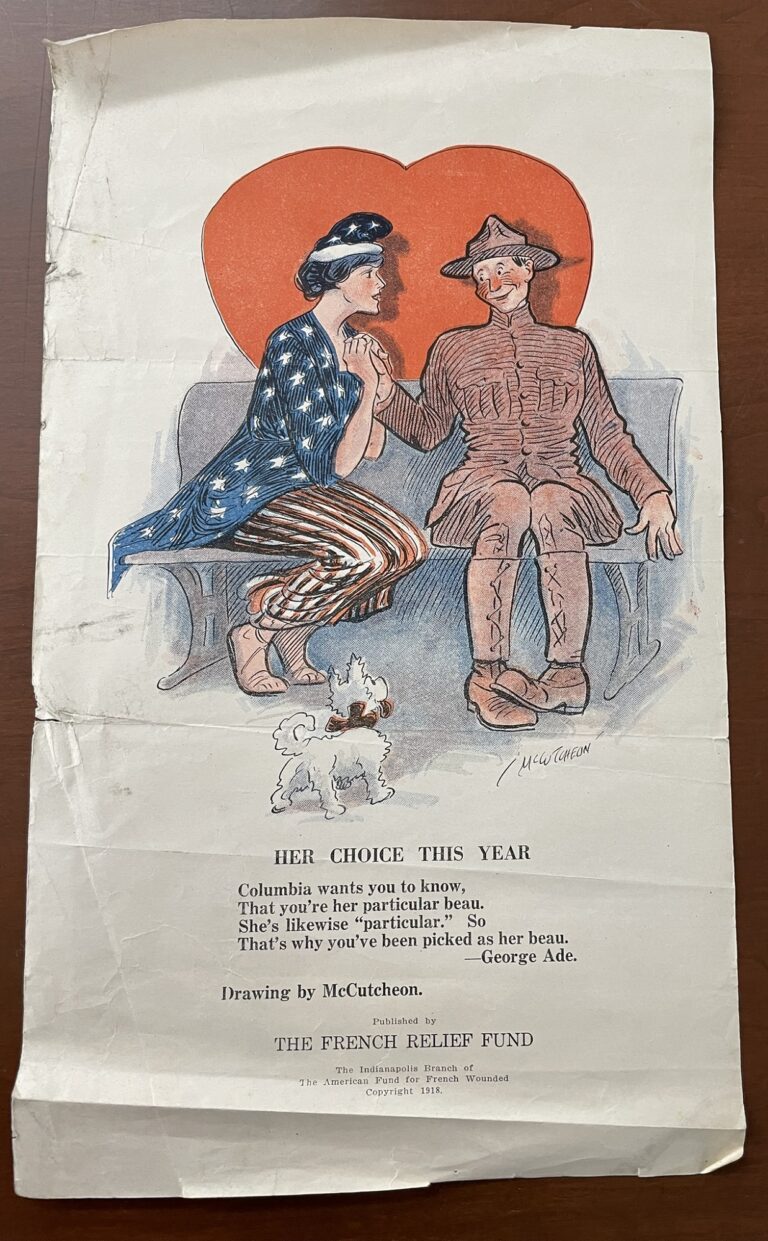

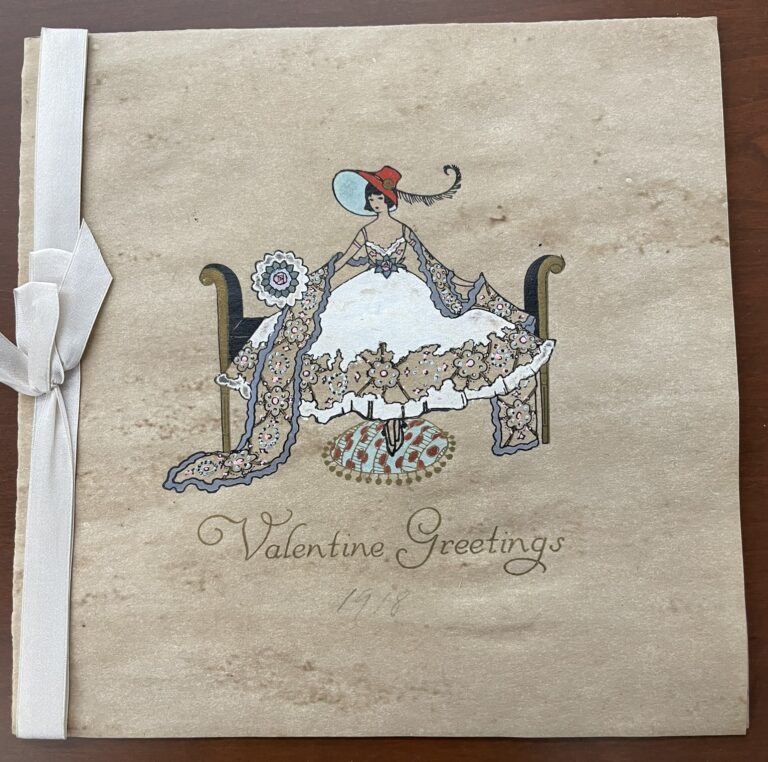

In our collection, there are two fabulous valentines from the 1910s—one that is clearly referencing World War I, and the other, with a handwritten “1918” in pencil, shows a woman in a short bob haircut, commenting on the old and new in verse, “Quaint and stately were the greetings sent by friends in days of old: just as true, sincere and tender are the thoughts my heart now holds.”

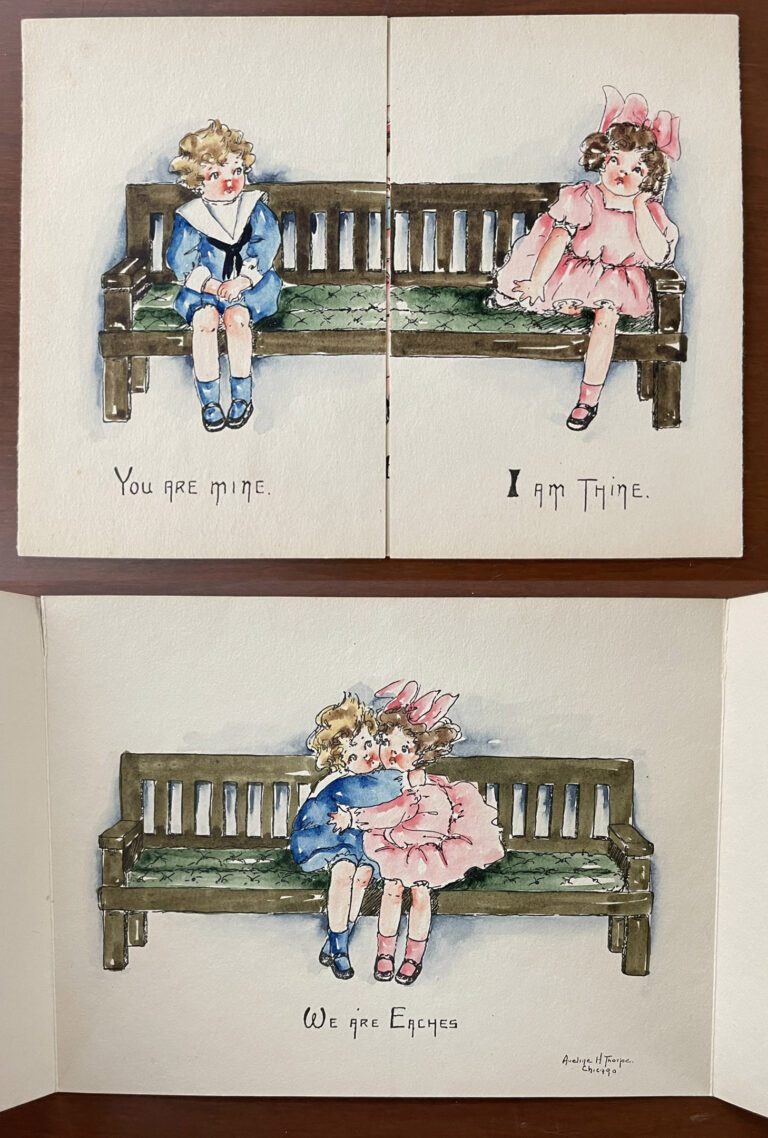

There’s another charming example from 1914 of a young girl and boy sitting on a bench, and the card opens to a sweet message. It also reads “Aveline H. Thorpe, Chicago.”

The name Aveline Thorpe shows up as someone involved with the Art Institute in the early 20th century and is listed in the 1923 directory as an artist living on North Winthrop Avenue. In the 1920 census, Frances Thorpe is listed as a commercial artist and her brother Homer as working in advertising for the Chicago Daily News, and in 1930, her brother James Jr. is listed as a salesman involved in engraving. In the Inter-Ocean paper, February 17, 1913, a Frances Aveline at that address held a valentine party at her home:

Frances’s mother is also Aveline (née Holman). It is unclear if this valentine was designed by mother or daughter. In the census, Aveline is not noted with a profession, but an Aveline Thorpe, designer, exhibited at the Art Institute in 1907—and Frances would only have been about 15 years old. Frances Aveline shows up later as a member of the Art Students’ League of Chicago in 1917.

From the 1920s through the 1950s, we start to see more of the cards we have become familiar with—printed, lots of bright colors, and hearts—and a now-household-name in the greeting card business—Hallmark!

Lastly, who doesn’t love cats and dogs for Valentine’s Day? Clearly, they have always been in fashion!

Additional Resources

- View the finding aid for our greeting card collection

- Learn more in Lester A. Weinrott, “Dear Valentine,” Chicago History (Winter 1974–1975):

- Read the Newberry Library’s blog post about vinegar valentines

- View the American Antiquarian Society’s online exhibition Victorian Valentines: Intimacy in the Industrial Age

- Read the American Antiquarian Society’s blog post on Esther Howland

Shrove Tuesday, more commonly known as Fat Tuesday, is a day in the Christian tradition that marks the end of the time before Lent. In this blog post, CHM curator of religion and community history Rebekah Coffman talks about the tradition’s practice, particularly in Poland and in Chicago’s Polish Catholic communities.

Ash Wednesday marks the start of a somber forty-day period of fasting in preparation for Easter. Many traditions around the world spend the days leading up to Lent as a time of partying, celebrating, and indulging before the restrained atmosphere of the Lenten season. This includes numerous rich food traditions as homes historically tried to use up indulgent ingredients like butter, sugar, and eggs before fasting. Foods often include pancakes, doughnuts, and other sweet pastries.

A variety of pączki flavors from Delightful Pastries in Chicago’s Jefferson Park neighborhood, 2024. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman.

In Poland and throughout the Polish diaspora, the start of the Lenten season is often synonymous with eating pączki. A sweet, doughnut-like pastry, pączki are made of yeasted dough and filled with jams or custards, with traditional flavors including plum and rose. In Poland, they are typically eaten on the last Thursday before Ash Wednesday, known as Tłusty Czwartek or Fat Thursday. The Tuesday before Lent is known as Herring Night (Śledzik), when it is traditional to eat herring and drink vodka, or Ostatki, meaning the “leftovers” or “last things” as a nod to the end of the celebratory season before the Lenten fast begins. In the United States, these two days are often merged, and Pączki Day has become largely conflated with other Fat Tuesday celebrations in cities with large Polish populations such as Chicago.

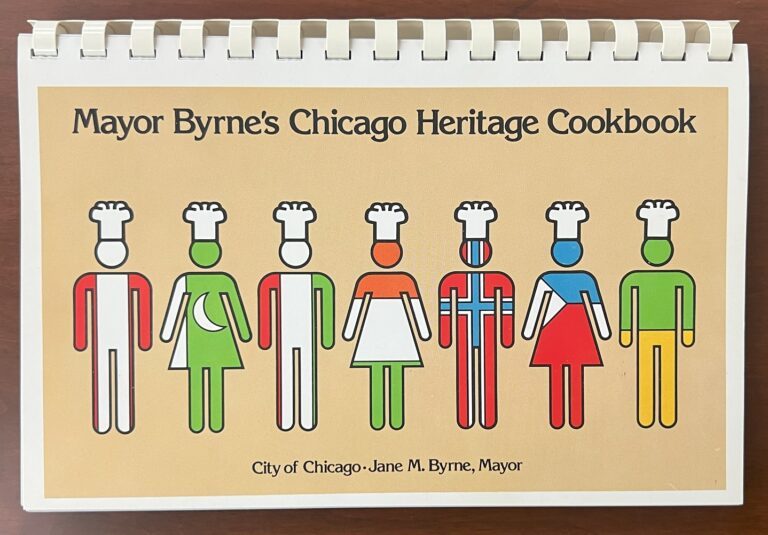

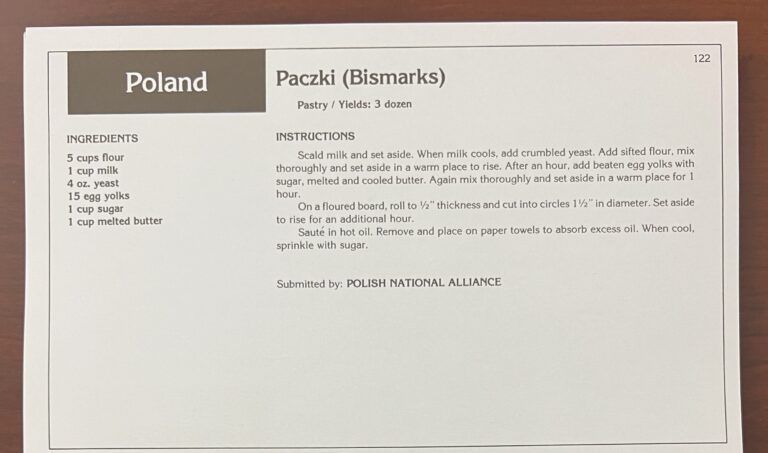

Cover of and recipe for pączki from Mayor Byrne’s Chicago Heritage Cookbook (1979). CHM Collection, TX725 .M2

While pączki may have historically religious roots, they have become just as much a mark of cultural heritage and have been adopted by Midwesterners beyond the Polish community. For example, Mayor Byrne’s Chicago Heritage Cookbook (1979) showcases Chicago’s cultural diversity through recipe highlights, including a section on Poland with a number of Polish favorites such as hunter’s stew (bigos), stuffed cabbage (golabki), dumplings (pierogi), and, of course, a pączki recipe contributed by the Polish National Alliance. The cookbook’s introduction notes that many of its contributors participated in the Chicago Heritage Parade and the Chicago International Festival at Navy Pier, and this showcasing of recipes and heritage was for the goal of “greater appreciation of Chicago’s ethnic diversity.”

Outdoor market in Polish neighborhood around Division Street and Milwaukee Avenue, Chicago, c. 1955. CHM, ICHi-175590; Stephen Deutch, photographer

As discussed in our exhibition, Back Home: Polish Chicago, Chicago has been shaped by nearly two centuries of Polish migration marked through four distinct waves: first from the 1850s to 1920s, next after World War II, then the Solidarity era of the 1980s, and again in the last decades of the 20th and into the 21st centuries. Core Polish neighborhoods were first established northwest of downtown Chicago along Milwaukee Avenue, with the area surrounding Milwaukee Avenue, Ashland Avenue, and Division Street earning the moniker of the “Polish Downtown.” This was soon followed by settlement in areas near industrial and trade work, including Pilsen, Bridgeport, Back of the Yards, South Chicago, Hegewisch, and other parts of Southeast Chicago. As time passed and agents of gentrification and ethnic succession took hold, families and communities moved further away from the historic core neighborhoods and into outer edge areas and the surrounding suburbs, including Portage Park, Jefferson Park, Archer Heights, Calumet City, Chicago Heights, and Cicero. With these shifts came the establishment of new businesses, places of worship, and community spaces.

Polish Constitution Day Parade near N. Milwaukee Ave. and W. Bryn Mawr Ave. in Jefferson Park, Chicago, 2000. ST-20002308-0018, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

For example, Jefferson Park in Chicago’s northwest has long been known as the “Gateway to Chicago” and served as an important transportation hub into the city, including as an extension of the core Milwaukee Avenue corridor. Around 1900, through its connections by street railway lines, large numbers of Polish, German, and Italian immigrants began coming to the area as laborers, artisans, and tradesmen. Though bifurcated by the construction of the Kennedy Expressway in the 1950s, the Polish community of Jefferson Park continued to grow in subsequent decades. Community institutions followed, such as the transformation of the former historic Gateway Theater into The Copernicus Center in the 1970s and 1980s. By 1990, almost half of those living in Jefferson Park were of Polish descent. Today, while the Polish community still has a strong neighborhood presence, Jefferson Park continues to become more racially and ethnically diverse with nearly 25% of residents identifying as Hispanic or Latine.

Exterior of Delightful Pastries at 5927 W. Lawrence Ave. in the Jefferson Park neighborhood, Chicago, 2024. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman

Various pączki flavors at Delightful Pastries include rose, plum butter, passion fruit jelly, and strawberry. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman.

Delightful Pastries in Jefferson Park is a delicious example of this rootedness within Polish tradition and culture while nodding toward multicultural influences. Owner Dobra Bielinski, born in Lubin, Poland, studied French at the Sorbonne, where she became inspired by Parisian pastries. She later studied culinary arts in Chicago, and 26 years ago she opened Delightful Pastries when presented with the opportunity to purchase a storefront on Lawrence Avenue. Dobra noted that, while pączki are a fried, yeasted dough like doughnuts, they are much less sweet than your everyday custard or jelly doughnut. Her Warsaw-style pączki are made with a traditional style dough and include old-fashioned flavors like plum, rose, and raspberry. However, her personal philosophy sees baking as something that has no borders and draws international inspiration as well. For example, her passion fruit pączki was inspired by a trip to Mexico and is filled with homemade passion fruit jelly, and her take on a strawberry shortcake includes strawberries and whipped cream in a halved paczek shell.

Wherever you buy, whatever flavor you love, and whenever you enjoy your pączki this pre-Lenten season, Niech słodkim nam będzie Tłusty Czwartek, and Happy Pączki Day!