Latest Posts

In this blog post, mount maker Michael Hall tells a story seen in the stitches of a Madame Merlot-Larchevêque dress he prepared for display in Dressed in History: A Costume Collection Retrospective, which opens on October 19, 2024.

There’s nothing more fun than deciphering a mystery! Historical costumes often come with many un-recorded secrets and as such, mounting them (putting them on a mannequin for display) for an exhibition can be difficult. A fantastic example of this is a gorgeous burnt orange and pink-striped Madame Merlot-Larchevêque silk taffeta dress, c. 1864.

Michael Hall adjusts the Madame Merlot-Larchevêque dress during photography.

Upon first assessment, the dress has many alterations that seem innocuous enough. However, after further inspection and a test fit, the skirt silhouette didn’t fully match the ascribed time period. With my interest piqued, I set to research the subtleties of silhouettes from the late 1800s. My research suggested the current skirt silhouette is dated to mid-1870 and not c. 1864. Mind blown, I returned to the dress itself and studied the aforementioned alterations to better understand why a dress dated c. 1864 appeared to be styled to a later silhouette.

Two dressed versions of the same skirt, one c. 1864 (left), the other c. 1870s (right).

In 1864, women’s fashion saw dresses that were full and round with a nipped waist, sloped shoulders with wide-cut sleeves, and high-set bust. Many of the dress’s original seam lines, cut, and shape all appeared to be from that date, but the alterations told a different story. In the 1870s, prevailing trends took the rounded skirt and swooped it toward the back to create a bustle, which at that time was quite voluminous. Jackets would still be nipped in at the waist, but the sleeves and shoulders would become more tailored.

I noticed the front panel of the skirt was crudely cut and quickly reattached by sewing machine without any attention to seam finishing or correct fit. It was reworked at the waist with an off-centered front panel, pleating that was unevenly replaced, and a hemline that was oblong and draped in a way that contradicted the c. 1864 date.

The front of the altered skirt at the waist.

The jacket is further nipped at the waist with additional pieces added to the hem for a grander flare. Additionally, the front of the jacket has loose and missing elements along with some signs of alterations that appear to suggest it was taken in.

Left: The exterior of the altered jacket with missing parts. Right: The interior with an additional piece inserted at waist.

One may ask, why would someone alter an already gorgeous dress? Simple—to keep up with the fashions of the day. It was not uncommon for people to alter, make repairs, or give older dresses to the younger generation who would modify the older styles into something more modern.

When the dress was photographed, it was styled as it would have been in the 1870s. CHM, ICHi-179975

So, how would I mount a dress that doesn’t have a clear silhouette and have it still be accurate, stable, and supported? I start with the assessment, move onto research, and then build the mount to correspond to the most current state even if it appears counter to what has been originally presented. Next time you see a dress on display that looks a little off, perhaps consider that it wasn’t originally made that way, but instead, was altered to be more “à la mode.”

Additional Resources

- Learn more about Dressed in History: A Costume Collection Retrospective, which opens October 19, 2024

- Purchase the Dressed in History: A Costume Collection Retrospective exhibition catalogue

- View more images of this dress and other images of items in our Costume and Textile Collection

- Visit the Abakanowicz Research Center to peruse our Costume Research Collection

In 2020, based on previous connections through the Museum’s exhibition, American Medina: Stories of Muslim Chicago, Chicago Theological Seminary (CTS) contacted CHM’s Studs Terkel Center for Oral History regarding collaboration around its Jackson Oral History Project (JOHP). The oral history center jumped at this opportunity to continue its goal of supporting collaborative community based oral history projects using tools of oral history for goals of social justice.

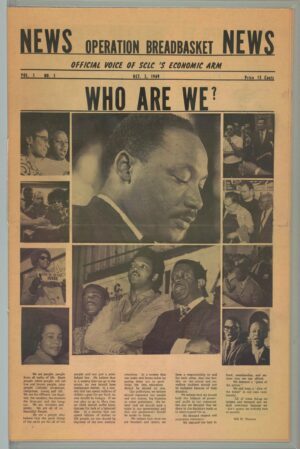

Operation Breadbasket News, the official voice of the movement; in this publication, Breadbasket proclaimed, “We believe, since we are brothers and sisters, we have a responsibility to and for each other,” October 3, 1969. CHM, ICHi-183715

In 1965, Rev. Jesse Jackson launched Operation Breadbasket (which later became Operation PUSH), a movement to help formally organize Chicago ministers to promote more employment opportunities for local Black individuals. Jackson was a student at CTS during the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, and his time at CTS shaped his career. He and his wife Jacqueline both spoke of the value of a CTS education in their early formation.

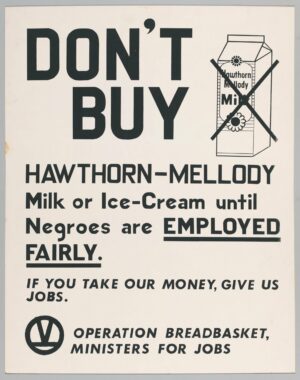

Operation Breadbasket protest poster urging consumers to boycott Hawthorn-Mellody products, 1966. CHM ICHi-183509

Through a generous grant from the Donnelley Foundation, CTS recently completed collecting an oral history of Rev. Jackson’s civil rights work in Chicago as a way to preserve the stories of the Civil Rights Movement in Chicago. Told by the people who lived and worked in the movement, these interviews are a window into a past that informs our present.

Interviewed by Rev. Brian E. Smith and Kim Schultz, the interview narrators include:

- Rev. David Wallace, former Chicago branch secretary for Operation Breadbasket

- Rev. Janette C. Wilson, advisor to Rev. Jesse Jackson and Director of PUSH Excel

- Rev. Martin Deppe, who worked with Operation Breadbasket

- Hermene Hartman, founder of N’DIGO Studio and publications

- Betty Massoni, wife of late Chicago activist Rev. Gary Massoni

- Rev. Jesse Jackson Sr., Civil Rights activist and head of the Chicago branch of Operation Breadbasket

In February 2024, a public launch of the JOHP took place in CHM’s Robert R. McCormick Theater. The evening’s event included listening to oral history clips and a discussion panel with the project narrators led by Rev. Smith, which you can view here. “The Jackson Oral History Project has been an unprecedented opportunity to capture stories from key figures in the Chicago Civil Rights Movement,” said Rev. Smith. “The archive documents in vivid detail the birth of this movement, showing how CTS acted as an incubator for the movement’s early leaders, including Rev. Jackson himself.”

Faith and lay leaders holding signs that spell out “Selma Wall” march from the Brown Chapel AME Church to police barricades set up a block away, Selma, Alabama, March 1965. CHM, ICHi-075291; Declan Haun, photographer

In partnership with CHM, the institutions used these oral histories to create an online exhibition featuring the under-told story of these Civil Rights activists working in the Chicago Breadbasket Movement, documenting the birth of this movement in Chicago and highlighting the importance of CTS as an incubator in that movement.

The online exhibition can be viewed below or at CHM’s Google Arts & Culture site. This online experience brings together JOHP excerpts and quotations with documents and photographs from the Museum’s varied collections. The full audio interviews along with photographs of the narrators are hosted online through CTS and can be found here.

The two organizations continue this initiative through an upcoming trolley tour of South Side Chicago sites highlighted in the JOHP and important to the Chicago Civil Rights Movement.

In 1980, a Chicago steel mill called Wisconsin Steel Works, large enough to take up most of South Deering, a community area on the city’s far South Side, closed its doors forever. Ownership of the mill had recently been sold by International Harvester, who had been using the mill for their farm equipment, to a very new company called Envirodyne, which had no experience in the industry. When their poor management led to the mill abruptly closing, however, it was the mill’s thousands of employees who dealt with the consequences. In honor of Labor Day, we’ll be looking at the history of how Chicago’s steel workers organized and cared for one another throughout the twentieth century, whether that be in a union, caucus, or autonomously.

When it originally opened in 1875, the mill was the Joseph H. Brown Iron and Steel Company. It became Wisconsin Steel Works under International Harvester in 1902. This letter W sign is from the Wisconsin Steel Works mill. CHM, ICHi-066079. In CHM’s Museum Collection, 2000.68.2.

Since steel mills first opened in the late nineteenth century, working in them has been a difficult and dangerous job. Steelworkers work with heavy machinery, fire, and molten metal. In an oral history interview for the Southeast Chicago Historical Society, Osborne Ferguson, who worked at the Acme Steel Plant from 1964 to 2001 said that the first day he went into the mill with just a shirt and pants on, the heat was so intense that he went and ate his lunch outside on the steps.

These steel-toed boots were owned and used by Herbert H. Post, a civil engineer, who worked at US Steel South Works from 1948 to 1977, designed to protect him both from the mill temperatures that could go above 110 degrees Fahrenheit as well as the heavy machinery he worked with. CHM, ICHi-040640_view01. In CHM’s Museum Collection, 2000.116.2a-b.

These jobs still drew in many people because of the community and the union benefits. In an interview for the Studs Terkel Center for Oral History, Roberta Wood, a steelworker, activist, and communist, described how she and lots of women began working in the steel mills after 1974 when organized African American workers fought for equal hiring rights across racial and gender lines. They found that they had many issues in common, like inadequate bathrooms, workplace harassment, and a lack of representation in their union leadership. Together, they formed a women’s caucus across multiple steel mills in the Chicago and Northwest Indiana area. As a result, they not only began to make gains for women in steel mills, but also were able to win leadership positions in the United Steelworkers union and create a community that Wood describes as a place they could be in community with and in support of one another.

This photograph was taken in 1985 at an outside gathering of some of the Save Our Jobs Committee members, including Juanita Andrade and Frank Lumpkin and others. CHM, ICHi-031930.

While the sense of community counted for a lot, the benefits like the pension plan, unemployment benefits, and insurance that the union had fought hard for also gave steelworkers the ability to provide for themselves and their families. These mill jobs were not easy to get other work with, as their skills were not easily translatable to a different industry, which made it all the more difficult for the workers of Wisconsin Steel Works when it abruptly closed in 1980. Neither International Harvester nor Envirodyne would give them the benefits or even the last cycle of pay that they were owed. So, one of the workers at the mill, Frank Lumpkin, worked with a group of former steelworkers to form the Save Our Jobs (SOJ) Committee, which organized demonstrations and legal work to get the mill reopened. When that became impossible, they turned to organizing to get the benefits owed to them. Eventually, they won their court settlements, which saved many people’s homes and lives.

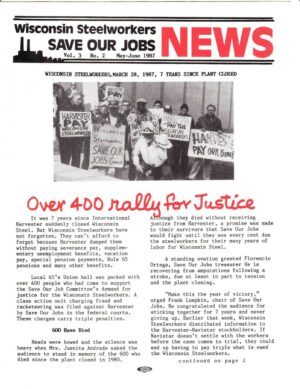

This is the front page of a newsletter issued by the Wisconsin Steelworkers Save Our Jobs Committee in 1987, reporting on a rally of over 400 people in support of the committee and the workers’ class action lawsuit to regain their benefits. It also recognizes the mourning and memory of the 600 former workers who had died within the seven years since the mill had closed. Wisconsin Steelworkers Save Our Jobs News, Vol. 3, No. 2, March 28, 1987. Southeast Chicago Historical Society Digital Archive, FIC-0000-054.

However, SOJ meetings and actions also served as a vital social support system for the unemployed steelworkers who faced isolation, depression, and rising cases of suicide. The SOJ cared for one another and recognized the struggles of their fellow workers, so they put on dinners and other events to make sure people were kept in their support. Chicago’s story of the SOJ shows that workers can organize and win in many different circumstances, and this year on Labor Day we should remember that community and solidarity go hand in hand in the fight for workers’ rights.

About the Author

Dan Murrieta worked this summer as a collections intern at the Swedish American Museum. He is an undergraduate student at Northwestern University studying History, Literature, and Latin American and Caribbean Studies.

Additional Resources

- Frank and Beatrice Lumpkin Papers at CHM’s Abakanowicz Research Center

- Chicago Cold War: Beatrice Lumpkin Oral History Interview

- Chicago Cold War: Roberta Wood Oral History Interview

- The HistoryMakers biography of Frank Lumpkin

- “Always Bring a Crowd”: The Story of Frank Lumpkin, Steelworker

- Resources from the Southeast Chicago Archive & Storytelling Project

- “The Closing of the Mills” web documentary

- Interview with Frank Lumpkin during Save Our Jobs Committee March

- Save Our Jobs Committee March and Meeting video

- Wisconsin Steelworkers Save Our Jobs News, Vol. 4, No. 2

- Wisconsin Steelworkers Save Our Jobs News, Vol. 3, No. 2

- Save Our Jobs Committee, Justice For Wisconsin Steelworkers panel discussion video

- Save Our Jobs Committee, Outside Wisconsin Steel Works photograph

- Tribute to Frank Lumpkin, Save Our Jobs video

At a time when depictions of African Americans in the media were largely negative and used racist stereotypes, Chicago-based Ebony magazine was founded in 1945 by John H. Johnson at the height of the Chicago Black Renaissance. It was the flagship magazine of Johnson Publishing Company, which published other iconic magazines including Jet and Negro Digest, and mirrored Life magazine’s format.

Ebony’s content initially focused on African American achievement and celebrity, but over time the magazine paid more attention to issues of social justice. Starting in the 1960s through the mid-1990s, once a year, typically in August, Ebony published a special issue devoted to timely themes with dramatic covers. Five of these issues are on display in our exhibition Designing for Change: Chicago Protest Art of the 1960s–70s. Learn more about these special issues below, and then come to the Chicago History Museum to see them in person.

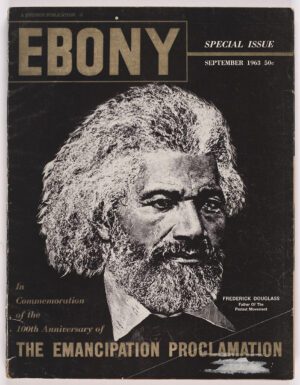

Ebony Special Issue: The Emancipation Proclamation, September 1963

Cover designed by Herbert Nipson and Norman Hunter

Ebony’s first special issue commemorated the 100th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation. But instead of Abraham Lincoln, who authored the decree, the cover featured Frederick Douglass, noted African American abolitionist who often criticized Lincoln for moving too slowly against slavery during the Civil War. The entire 236-page issue was devoted to 100 years of hope and struggle for African Americans and contained contributions from guest authors, including President John F. Kennedy and former Presidents Hoover, Truman, and Eisenhower. In a “Statement from the Publisher,” John H. Johnson wrote that the Emancipation centennial is “a time for rededication to the unfinished business of eradicating segregation and discrimination from every facet of American life.”

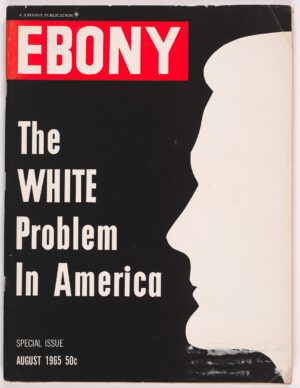

Ebony Special Issue: The White Problem in America, August 1965

Cover designed by Herbert Temple

At the height of the Civil Rights Movement, Herbert Temple, Ebony’s lead designer, created this provocative cover that addressed American racism. Temple, a graduate of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, also designed for Negro Digest/Black World, also on view in Designing for Change. The issue was devoted to examining the “race problem” in the United States with a “thorough study of the man who created the problem.” The “Publisher’s Statement” reads: “In this issue we, as Negroes, look at the white man today with the hope that our effort will tempt him to look at himself more thoroughly. With a better understanding of himself, we trust that he may then understand us better—and this nation’s most vital problem can then be solved.”

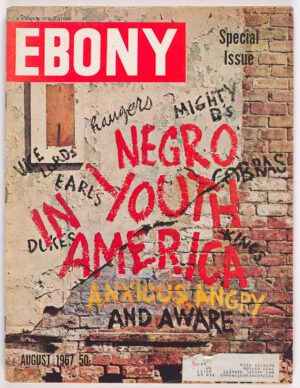

Ebony Special Issue: Negro Youth in America, August 1967

Cover designed by Cecil Ferguson

This issue focused on challenges faced by African Americans under age 25, including economic hardships, gangs, education, employment, and rural isolation. It also looked at the contributions Black youth made to inspire the sit-in movement as well as the arts, like popular dance and music. These topics were then combined to focus on the challenges youth face in having the educational and economic tools they need to extend into adulthood the cultural contributions they have already made. The cover of the issue was based on a mural created by Ebony artist Cecil Ferguson and photographer Lacey Crawford. Note, the term “Negro” remained in use at the time, but it was losing favor to the more contemporary term “Black.”

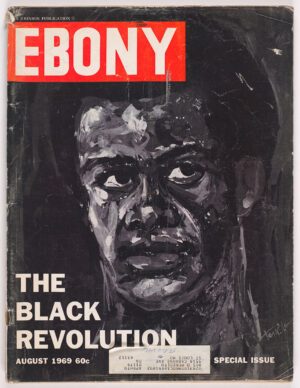

Ebony Special Issue: The Black Revolution, August 1969

Cover designed by Herbert Temple

Ebony addressed the Black Power Movement in this issue with a dramatic cover portrait of a “Black Revolutionary” by Herbert Temple. Staring with a “Publisher’s Statement” that acknowledged an end to the promise of the March On Washington following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. the previous year, the issue featured many articles expressing different points of view on the Black Revolution. Contributions came from Black leaders, philosophers, activists, and historians, including “The Black Panthers” by Huey P. Newton and “The Myth of the Revolutionaries” by longtime Civil Rights leader Bayard Rustin, who was more critical of the movement.

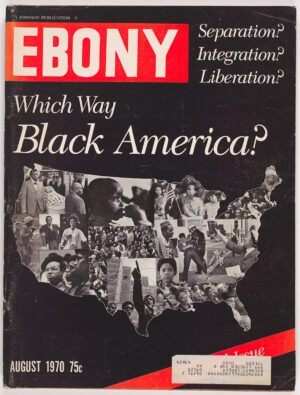

Ebony Special Issue: Which Way Black America?, August 1970

Cover designed by Herbert Temple

Herbert Temple’s cover illustrates the conversation among African Americans about “just where the black man stands in America today.” The issue brought together thinkers representing separatist, integrationist, and liberationist perspectives. Among these articles were “Integration” by Roy Wilkins and “A Dialogue on Separatism” by Jesse Jackson Jr. and Alvin Puissant. Lerone Bennett Jr. also contributed an article about the historical roots of racial division dating back to colonial America. In his “Publisher’s Statement,” John H. Johnson noted that in spite of the wide range of views, “there is a stronger unity among blacks today than at any other time in history.”

Additional Resources

Today, ADAPT is a grassroots disability rights organization that organizes nonviolent direct action and acts of civil disobedience to fight for the civil and human rights of people with disabilities. But when ADAPT began in 1983 it stood for Americans Disabled for Accessible Public Transit, with a specific focus on wheelchair accessibility on public buses.

The first protests took place in Denver in July 1978, but throughout the 1980s, the campaign for bus lifts expanded to cities across the country, including Chicago. On August 25, 1984, wheelchair users of ADAPT held a rally at South State and West Jackson Streets to pressure the Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) to install wheelchair lifts on its mainline buses. Disability activists continued to disrupt CTA board meetings and block CTA buses, and in 1985, ADAPT sued the CTA for discrimination.

Wheelchair users of ADAPT gather for a rally at South State and West Jackson Streets, Chicago, to pressure the CTA to install wheelchair lifts, August 25, 1984. ST-20001256-0014 (above), ST-20001256-0006 (below), Chicago Sun-Times collection, Chicago History Museum

Finally in 1988, a judge ruled that the CTA’s “Dial-A-Ride” service was not an adequate alternative to accessible buses, and that year, the CTA board voted to equip more than 500 new buses with wheelchair lifts. The victory in Chicago was encouraging, but activists wanted stronger laws passed at the federal level that would not only give them access to transportation but to jobs, housing, and education. ADAPT continued to protest and demand that Congress pass the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). Their actions included a march from the White House to the Capitol in Washington, DC, on March 12, 1990.

President George H. W. Bush signed the ADA into law on July 26, 1990. The legislation “prohibits discrimination against people with disabilities in several areas, including employment, transportation, public accommodations, communications and access to state and local government programs and services.”

ADAPT’s work to improve access to public transportation is only part of its platform of community for all, where all people can live, move, and participate in ways that recognize and support individual dignity and freedom. This includes eliminating barriers to things like work, health care, and disaster relief, but also changing the way disability is thought of, so disabled lives are seen as having value. A focus of ADAPT Chicago’s work has been on housing, specifically the right to live in one’s home rather than a nursing home.

Protestors from ADAPT block an entrance to the U.S. Health and Human Services department on West Adams Street, in response to a lack of government funds allowing people with disabilities to live at home, Chicago, May 11, 1992. ST-30002316-0042 (above), ST-30002316-0066 (below), Chicago Sun-Times collection, Chicago History Museum

The independent living (IL) movement has been at the cornerstone of the disability rights movement in the United States since the 1960s. IL developed in response to people with disabilities being routinely institutionalized and separated not only from society but from making their own choices. The IL movement asks for the recognition that people with disabilities are the experts on their own needs, with the point not that they don’t need some assistance, but that they should be making decisions for themselves.

ADAPT continues its work to advocate for services, legislative policy changes, grassroots education and mobilization through rallies, sit-ins, protests, campaigns, and national field events. They also continue to advocate for transportation access. Most recently, in 2016, during an event marking the 25th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act, CTA President Dorval R. Carter Jr. announced a plan make all 145 elevated and subway rail stops in the city wheelchair accessible by 2038. You can track the progress on the CTA’s website.

Additional Resources

- See more images from ADAPT’s protests in Chicago at CHM Images

- Find research materials using CHM’s Disability Research Guide

- Listen to Studs Terkel’s interview with Susan Nussbaum, founder of Access Living, and Michael Pachovas, founder of Disabled Prisoners Program, about the Disabled Persons Freedom Rally held in 1981

As part of the Chicago History Museum’s Aquí en Chicago project, a Community Awareness Council was formed and is charged with: (1) building relationships among and across the Chicago area’s many different Latine communities, (2) bringing as many voices to the table as possible, (3) networking through this group, and (4) learning of ways the Museum can serve diverse Latine communities.

Ashley Dequilla was invited by CHM curator of civic engagement and social justice Elena Gonzales to be a Council partner. In this blog post, Dequilla writes about her role as the de facto archivist and collection manager of the Filipino American Historical Society of Chicago. She is also the moving image archivist at University of Chicago South Side Home Movie Project.

In October 2022, I attended a Filipino American History Month program at the Skokie Public Library that led to an encounter that would unknowingly change my life and history itself. It was there that I connected with Tito Ruben Salazar, a respected community organizer who wished to introduce me to Estrella Alamar (1936–2022), a self-taught cultural historian and the founder of the Filipino American Historical Society of Chicago (FAHSC). The FAHSC was established in Chicago’s Hyde Park community area as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization in 1986 with the sole mission of recording, preserving, and sharing Filipino American history within the greater Chicago area. The FAHSC collection comprises historical photographs, documents, newsletters, posters, cassettes, tapes, analog films, cultural artifacts, and more.

The weekend I was supposed to meet Estrella to film her interview, she lost her battle to cancer. I felt extremely compelled by the untimeliness of her death and the urgent need to care for the legacy she left behind. I was the videographer of her funeral, and then I volunteered at her home in Hyde Park every weekend in 2023. A loving and devoted team of volunteers wished to salvage the overwhelming mass of historical materials (and other things) that she accumulated throughout her life. By the end of the year, more than 400 boxes of ephemera were compiled and moved to storage at the HANA Center in Albany Park and are now in the beginning stages of processing with support from DePaul University’s Special Collections team of archivist consultants.

Chicago of Today (1936) is an architectural survey featuring sweeping views of downtown Chicago, Garfield Park Conservatory, University of Chicago, and Lincoln Park Zoo. All film stills courtesy of the Filipino American Historical Society of Chicago

After Estrella’s passing, I stepped into the role of FAHSC’s de facto archivist and collection manager with the intention of stabilizing the archive toward long-term preservation and raising awareness of it for scholars, artists, and community members. I partnered with University of Illinois Chicago’s Special Collections to safehouse paper documents, such as photographs and documents, and with the Chicago Film Society and the University of Chicago’s South Side Home Movie Project (SSHMP) to digitize and preserve audiovisual material such as slides, reel-to-reel audio, cassette tapes, and analog film. A selection of digitized items can be viewed online through the Chicago Collections Consortium.

Calumet Park (1939) shows footage of the Nueva Vizcaya Association community members engaged in leisure activities in and around Chicago, notably featuring FAHSC founder Estrella Alamar.

The Filipino American Historical Society of Chicago collection has more than 300 16mm film reels that date from 1926 to 1990. These films are priceless and groundbreaking material as autonomous filmic evidence of Filipino American people from the first half of the 20th century. Nicholas G. Viernes (1902–91), lovingly referred to as “Uncle Nick,” was the filmmaker behind the camera for most of this collection. Viernes immigrated to the United States by ship in 1926, arriving in the Pacific Northwest and working as a migrant farmer until finally settling in Chicago.

All-Star Baseball Meets at Grant Park (1939) has footage of an inter-state Filipino migrant league baseball championship in front of the Field Museum of Natural History.

He was considered the unofficial Filipino community film historian and cameraman, documenting many events on 16mm film. His life on film features travel, community events and gatherings, family celebrations, and leisure activities.

Little Farmers of Reynoldsburg (1936) and Reynoldsburg Pt. 2 (1937) are home movies documenting an interracial Filipino American family’s life on a farm in rural Ohio.

Only five out of 350 films made in the Philippines prior to World War II have survived. The FAHSC has over a dozen prewar home movies made by Viernes that recover the loss of Philippine cinematic memory across the diaspora. The National Film Preservation Foundation (NFPF) has selected five of the earliest and most historically significant pre-WWII FAHSC films for federally funded grant awards to ensure their full preservation: Little Farmers of Reynoldsburg (1936) and Reynoldsburg Pt. 2 (1937), All-Star Meets at Grant Park (1939), Chicago of Today (1936), and Calumet Park (1939).

Little Farmers of Reynoldsburg (1936) and Reynoldsburg Pt. 2 (1937) are home movies documenting an interracial Filipino American family’s life on a farm in rural Ohio.

We invite you to learn more about the Filipino American Historical Society of Chicago at one of our upcoming events.

- Saturday, August 24, 10:00 a.m.–2:00 p.m. – Archive Crawl at the HANA Center

- Friday, August 30, 7:00 p.m. – Presentation and screening of NFPF-awarded films at Chicago Filmmakers

- Friday, October 18, 2:00 p.m. – Presentation and screening of NFPF-awarded films at the Harold Washington Library Center

- Saturday–Sunday, October 19–20 – Filipino American Historical Society of Chicago Museum reopens after 21 years, which is the FAHSC mission and Estrella’s dying wish. Visit us in Studio 316 at Mana Contemporary.

If you’re interested in donating to, becoming a member of, or volunteering with the Filipino American Historical Society of Chicago, please email us at fanhs.greaterchicago@gmail.com

Special thanks to Mónica Félix + Chicago Cultural Alliance, and Elena Gonzales + Aquí en Chicago.

Mrs. John Barry standing, holding kittens at a cat show, Chicago, 1906. DN-0004489, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

International Cat Day was started on August 8, 2002, to raise awareness about care and protection of domestic cats, but cat appreciation dates back much further in Chicago. The city is home to one of the first cat fancier organizations, or cat breed registries, in the United States—the Beresford Cat Club of America.

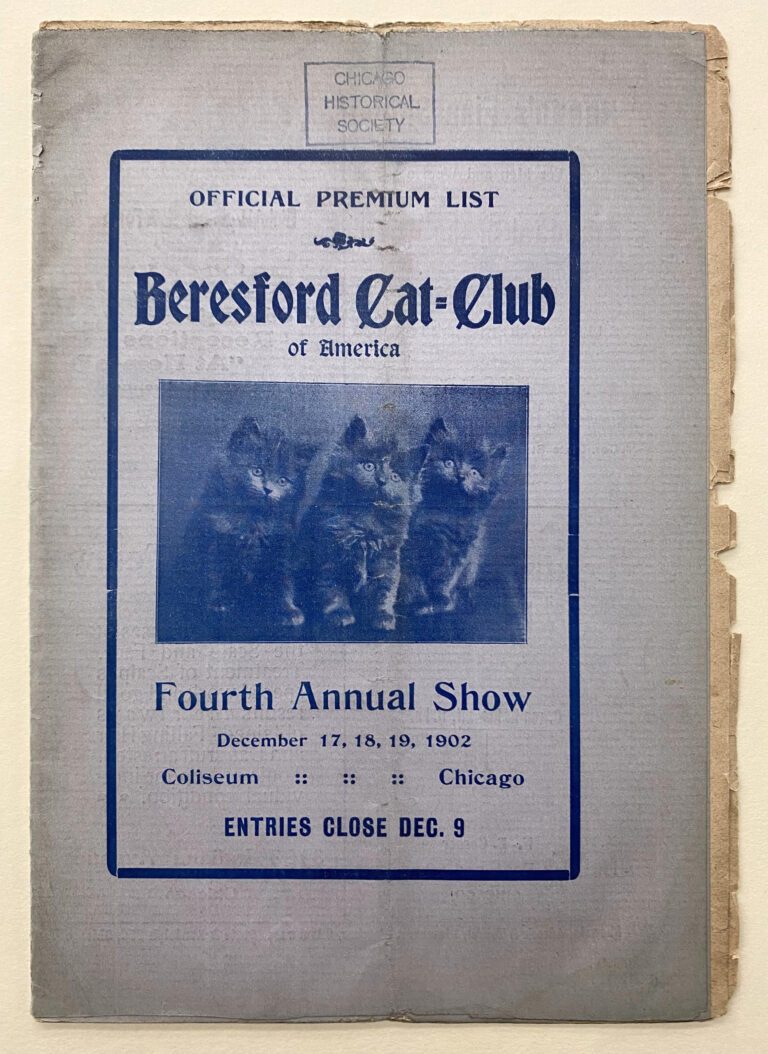

Cover of the Beresford Cat Club’s Fourth Annual Show Official Premium List, 1902. Photograph by CHM staff

The Beresford Cat Club was organized in 1899 and named after Lady Marcus Beresford (née Louisa Catherine Ridley), a cat breeder who in 1898 formed the Cat Club in England. Lady Beresford was a friend of the Beresford Cat Club’s first president, Mrs. Adele Clinton Locke, who kept, bred, and imported cats along with her duties as the wife of a rector of Grace Episcopal Church in Chicago. She supported charitable works in the city with the income she earned from her cat kennels and encouraged her friends to breed cats and exhibit them at shows to supplement household income.

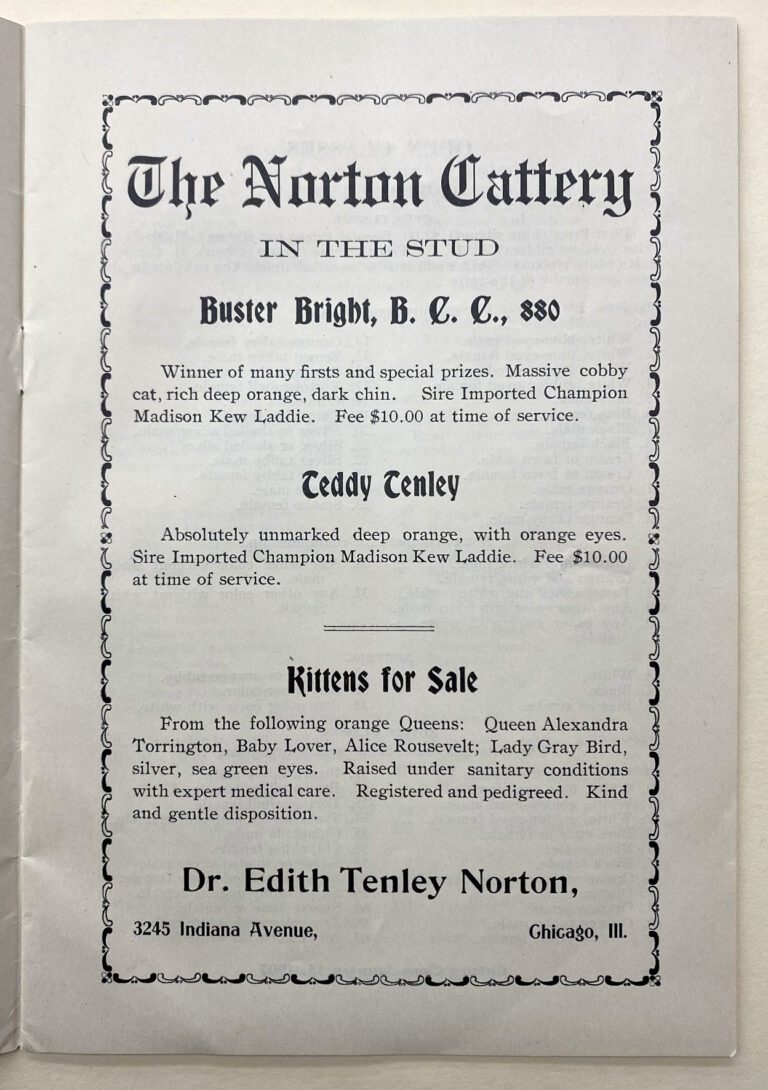

Advertisement for the Norton Cattery in the 1907 Beresford Cat Club show’s Official Premium List. Photograph by CHM staff

Though the club was officially national, many of the early officers of the club were Chicago-based. In 1899, Mrs. Locke was joined by: vice presidents Mrs. Josiah Cratty, Mrs. Eames Colburn, treasurer Mrs. Charles Hampton Lane, corresponding secretary Mrs. Chauncey F. Smith, and recording secretary Mrs. Charles DeWitt. The club’s first board of directors were Mrs. Elwood H. Tollman, Mrs. William Penn Nixon, Mrs. Jerome H. Pratt, Mrs. M. Fisk-Green, and Miss Lucy C. Johnstone.

Portrait of John G. Shortall captured by the studios of William J. Root, c. 1892. CHM, ICHi-065460

The club was sanctioned by John G. Shortall, one of the Chicagoans who created the Illinois Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in 1869. Shortall was also instrumental in the formation of the American Humane Association in 1877, which he hoped would lobby Congress “to protect animals in transit from the West to the East.”

The Beresford Cat Club started the American Stud Book on Cats, thus establishing a registering body for purebred cats in the United States. The first four volumes of the stud book were published between 1899 and 1905. The club also established the first American Cat Show Rules, which standardized the evaluation of cats at US cat shows.

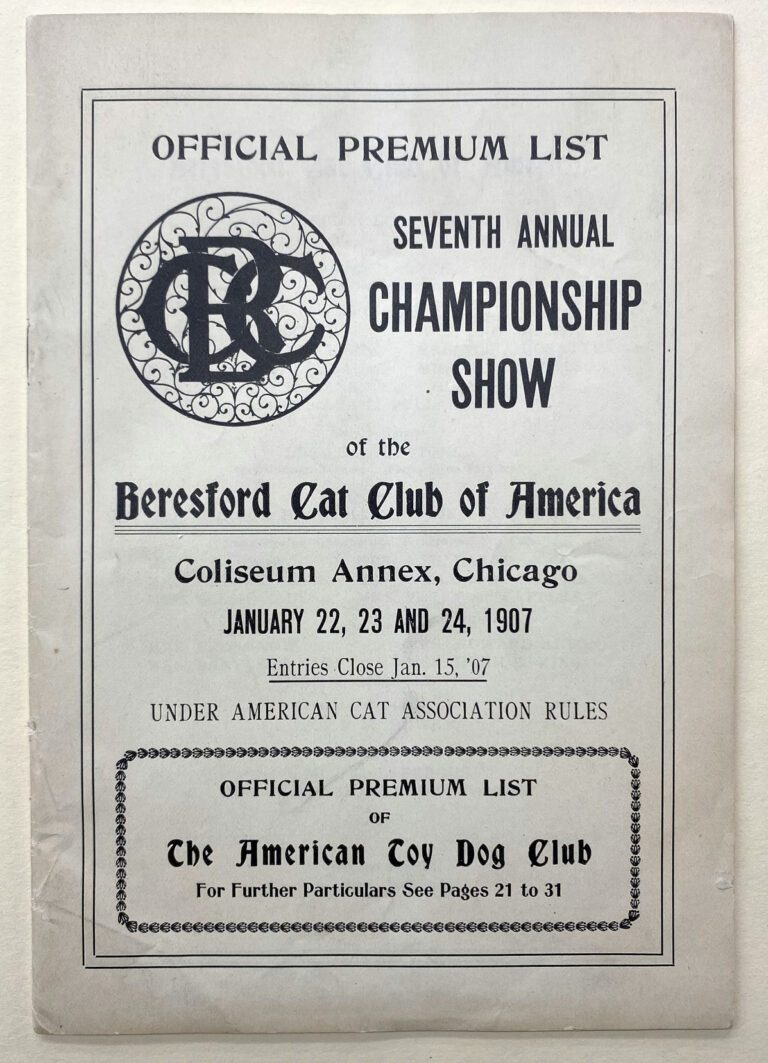

Cover of the Beresford Cat Club’s Seventh Annual Champion Show Official Premium List, 1905. Note the “Under American Cat Show Rules.” Photograph by CHM staff

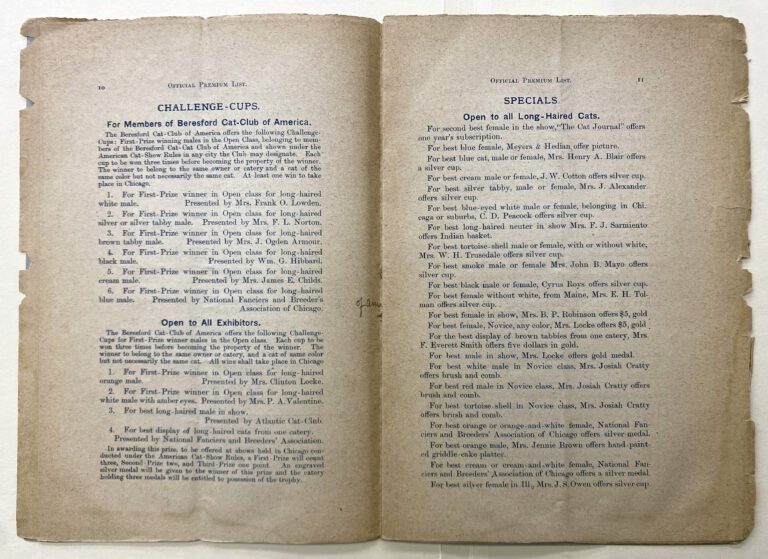

With these rules in place, they hosted an annual cat show in Chicago. At these shows, cat and cattery owners would show their cats in classes according to their cat’s coloring and markings. They gave cash prizes in numerous categories and to cats of all types, from pedigree breeds to “novice” classes. Special awards were also sponsored by individuals who offered prizes of medals, silver cups, and brushes. At their January 1900 show, they handed out 178 prizes, making them one of the most successful cat shows in the country.

Pages from the 1902 Beresford Cat Club show’s Official Premium List. Photograph by CHM staff

Other cat fancier clubs existed in the United States at the time, including the Cat Fanciers’ Association, which split from the Beresford Cat Club following the 1906 annual meeting, but for a short period of time the Beresford Cat Club was the most powerful cat society in the country. The club renamed itself to the American Cat Association in 1906, and the organization continues to this day.

Mrs. J. M. Adam, president of the Cat Fanciers’ Association, holding a cat named King Vodo, Chicago, 1908. DN-0005749, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

You can find the documents featured in this post at CHM’s Abakanowicz Research Center (call no. F38MB.B4), which is always free to visit.

In anticipation of our upcoming exhibition Dressed in History: A Costume Collection Retrospective, CHM assistant conservator for costume and textiles Julie Benner wrote about the process of conserving a Christian Dior gown for its first time on display.

This stunning Christian Dior gown, called Fidélité, was originally conceived as a wedding dress for Dior’s autumn/winter 1949 collection. It was donated to CHM in 1983 by Ms. Jeanne B. Heinzelman, née Jeanne Brucker. She won the gown from Marshall Field & Co. by raising the most donation money for Passavant Memorial Hospital (now Northwestern Memorial Hospital) and wore it to the 1949 Passavant Cotillion and Christmas Ball.

Portrait of Miss Jeanne Brucker in her Dior gown, December 23, 1949. CHM, ICHi-074220

In addition to its unique backstory, another of the gown’s distinctions is its scale: with a skirt diameter of around 6 feet and weighing in at 35 pounds, it is the largest single object to be displayed in Dressed in History. The weight comes from over a hundred yards of fine net (also known as tulle) pleated around the bodice and gathered in voluminous layers throughout the skirt, and nine yards of satin draping that wind around to a fashionable knot in the back of the train.

When the conservation team examined the gown for exhibition, it was clear that we had work to do to ensure its stability for display and revive its signature appeal. After decades of storage, the fabrics were creased, distorted, and exhibited a yellowish cast. We noticed tears, snags, and numerous unstable previous repairs throughout the net, as well as detached fasteners and tacking threads. We set to work documenting its condition, taking measurements for mounting, and developing our treatment plan.

In March 2023, the Dior gown (1983.28.1) underwent a condition assessment before treatment. Note the creasing and distortion of the net skirts and satin drape. Photograph by Julie Benner

We began treatment by surface cleaning the entire exterior and throughout all layers of the skirt to reduce dust accumulation, using a HEPA-filtered variable-speed vacuum on its lowest power setting, further reducing the suction by using a vented hose fitted with micro-attachments.

With the tireless help of conservation volunteer Mia Mehta, we vacuumed systematically through the seemingly unending layers, tracking our work by placing temporary stitches in bright cotton thread to mark our progress, as there was no obvious line between vacuumed and unvacuumed areas.

CHM conservation volunteer Mia Mehta methodically vacuumed the layers of net throughout the skirt to reduce dust. Photograph by Julie Benner

The vacuuming process also gave us the opportunity to thoroughly inspect every inch of the net for damages to mark their locations with temporary stitches in another thread color for later repair.

After the surface cleaning, I stabilized areas of damage using a finely loomed nylon bridal net special-ordered from England, securing patches behind holes and tears with silk hair thread. Unstable previous repairs were replaced or modified. Loose fasteners and detached tacking threads in the bodice were re-secured with fine cotton thread.

Assistant conservator Julie Benner used insect pins to position a small patch of fine nylon net behind an area of damage in the skirt before securing it in place with silk thread. Photograph by Paulina Budzioch

Once cleaned and stabilized, the most dramatic part of the transformation could now take place. Together, conservation mount maker Michael Hall and I dressed the gown on the mount that he fabricated and customized to the gown’s dimensions. Michael then carefully and painstakingly humidified the skirt layers using a gentle mist of deionized water. The net relaxed readily with his efforts, and the skirts became lofty and luminous.

Now exhibit-ready, the gown embodies a striking contradiction: displaying an abundance of softness and delicacy while commanding attention and unapologetically taking up space.

The left oblique view of the Dior gown, 2024. CHM, ICHi-180000

Additional Resources

- Learn more about Dressed in History: A Costume Collection Retrospective, which opens October 19, 2024

- Purchase the Dressed in History: A Costume Collection Retrospective exhibition catalogue

- View images of items in our Costume and Textile Collection

- Visit the Abakanowicz Research Center to peruse our Costume Research Collection

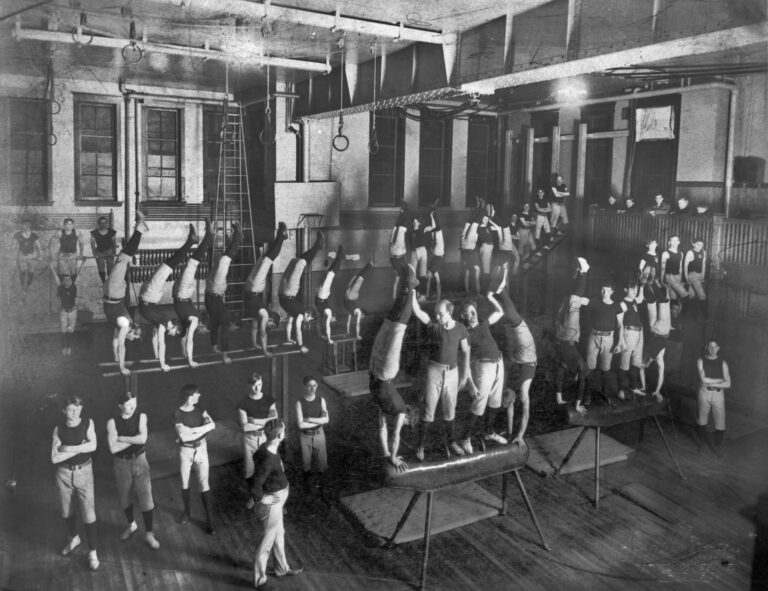

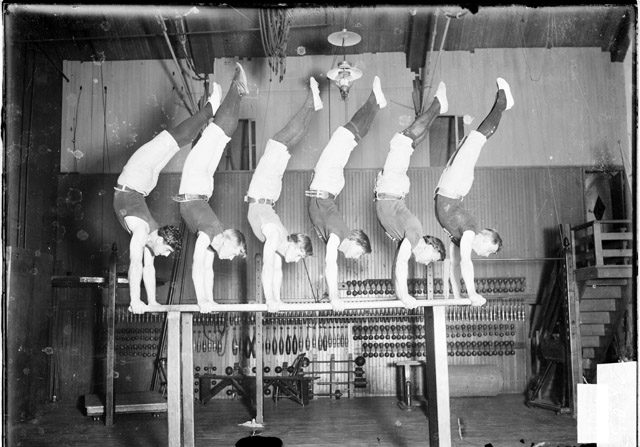

In 2021, gymnastics was the most viewed summer Olympic sport by US audiences (Source: Statista), and chances are if you’re reading this, you’ve done a summersault or two at some point in gym class. But how did this sport first gain prominence in the United States?

In 1811, centuries after the ancient Greeks coined the term gymnastikē, which is derived from gymnazo (nude physical training), a soldier named Friedrich Ludwig Jahn created an open Turnplatz (field) in Berlin, Prussia, where clothed young men could exercise on rudimentary gymnastics equipment in the hopes that they might not suffer the same defeat the Prussian army did at the hands of Napoleon. Later known as the “Father of Gymnastics,” Jahn invented much of the equipment central to the modern sport: parallel and horizontal bars, pommel horse, rings, and balance beam.

Practitioners of Jahn’s techniques formed nationalist groups known as a Turnverein (gymnastics association) and called themselves “Turners.” These Turners were active participants in many of the German uprisings of 1848 and 1849, and when these revolutions failed, “48-ers,” or liberal-minded defectors from the German Confederation immigrated to the United States throughout the 1850s where they continued to form Turnverein wherever large populations of Germans settled.

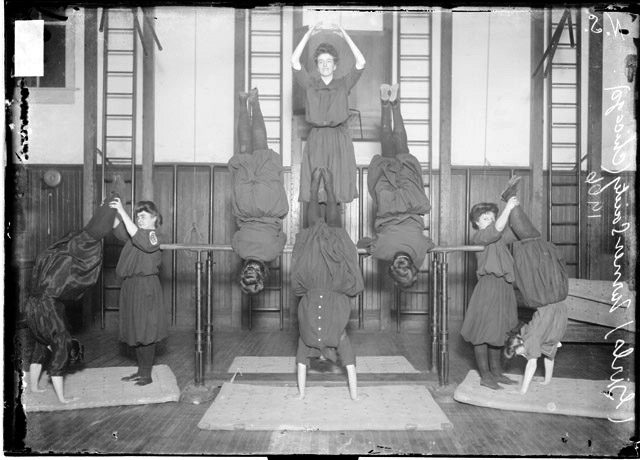

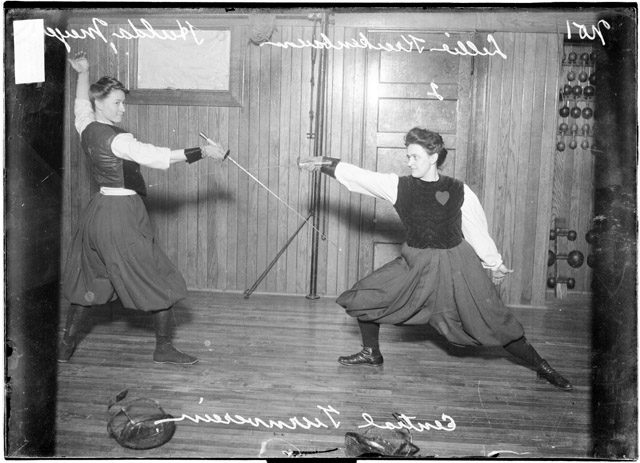

By 1906, there were 24 different independent Turner organizations in Chicago, all sharing a dedication to incorporating physical education into school curriculums and creating ample opportunities for exercise in their own community centers, or Turnhalles (Turner Halls). In addition to gymnastics classes, the Turnverein organized sports league opportunities for young and old, from fencing and wrestling to basketball and indoor baseball, as well as offering outdoor excursions and summer family camps outside the city. Classes were typically divided by age and gender (there were even gymnastics classes targeted at businessmen), and women were allowed a greater degree of participation in gymnastics and sports classes from the 1880s onward.

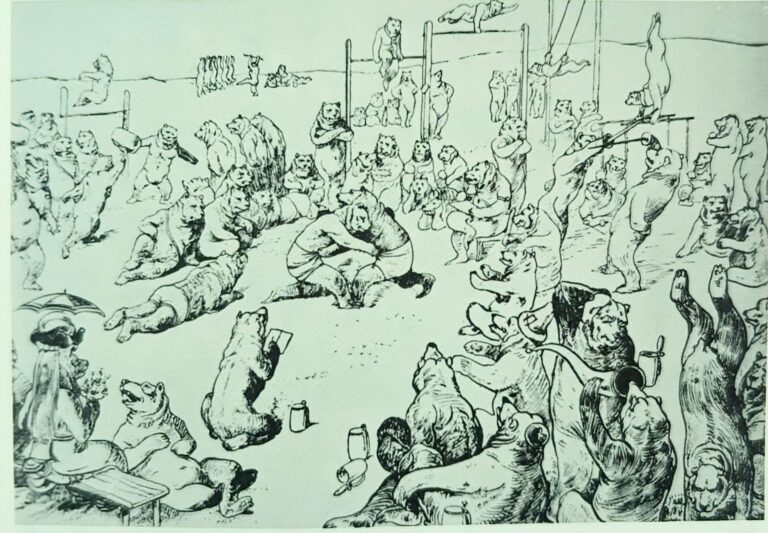

Beyond athletics, Turner Halls hosted practice sessions for drama groups, musical instrument corps, and choirs, that would perform at various pageants and Turnfests (gymnastics festivals) throughout the year. These halls also served as spaces for social gatherings for the public and members alike, ranging from dances to union meetings. Most Turner Halls also had at least one bar or biergarten!

Many Turnvereins also held socialist ideals, underscored by a 1919 program from the Turnverein Lincoln, or Lincoln Turners, declaring “A Turner is a—man—or woman—of liberal and harmonious education of body and mind—a believer in life and its beauty and its perpetuation ever nobler and inspiring ideals. Should be cheerful, happy, sympathetic, charitable, tolerant, striving for the truth and justice, and for promoting the social and economic condition of all” (Source: MSS Lot Lincoln Turners Box 3, Souvenir Program for the Grand Colonial Fair and Bazaar, 1919)

The Chicago-based Turn Verein Vorwaerts (Forward Turners) established a hall on Meagher Street near Canal Street, and their original rules and restrictions for this hall convey the mixture of strict discipline, solidarity, and fun for which the Turners stood:

- No Turners allowed to relax during classes.

- All class members must partake in all physical activities, meets and other competition.

- Turners must serve as bartenders and waiters at all functions.

- Turners must attend the funerals of all fellow Turners.

- Playing cards in the Turner Hall on Sunday is strictly forbidden.

- Failure to abide by rules and regulations immediately punished by fines and disciplinary action.

- Repeat offenders expelled.

(Source: History of the Turnverein Vorwaerts by William R. Meyer, p. 4)

Turners frequently touted that their gymnastics training made them especially prepared for military service, and many served in the US army during the Civil War and both World Wars. In a 1919 extract from the Chicago Daily News, Commanding Officer Neuendorf observed that in his experience, “a military education as preparation for future military service is not desirable…a skilled ‘turner,’ an ambitious athlete, a man who takes long tramps, can grasp the specialized part of military training with ease” (Source: MSS Lot Lincoln Turners Box 3, Souvenir Program for the Grand Colonial Fair and Bazaar, 1919).

It turned out that gymnastics training also led Turners to become strong competitive gymnasts, and in 1985, one of the Chicago-based Turnverein, the Lincoln Turners, proudly noted that since women’s gymnastics was introduced at the Olympics in 1928, five women from their organization had represented the United States at the competition! Though memberships declined throughout the 20th century, the Turners played a critical role not only in establishing a vast network of German community centers, but also in helping popularize the modern form of gymnastics that continues to enthrall us today.

For further reading:

- Records of the Lincoln Turners, ca. 1885-1994.

- William R. Meyer, History of the Turnverein Vorwaerts : Forward Turners of Chicago, Illinois July 24, 1867 – February 12, 1956

- Turnvereins, The Encyclopedia of Chicago

- Learn more about one of Chicago’s surviving Turner Halls, the Turner Vorwaerts Hall here.

Since January 2024, CHM curatorial volunteer Nez Castro, a senior in history at University of Illinois Chicago, has been working with CHM curator of civic engagement and social justice Elena Gonzales on a key component of an upcoming exhibition. In this blog post, he writes about working on the Digital Communities’ Scrapbook, a crowd-sourced project.

The Digital Communities’ Scrapbook is an album of crowd-sourced photographs that will appear in Aquí en Chicago, an exhibition celebrating Latine communities’ historically persistent cultural presence in Chicago. Through it, visitors can view images from CHM’s collection and those I have gathered during the last six months of exploring Chicago. They can also share their own photographs, adding their memories to a larger story of the people, places, and events that form Chicago’s Latine history. The scrapbook will show the presence and diversity of these communities using these images. A critical part of this will be built of photographs submitted by visitors and readers like you.

In late February, I met with the Rodriguez family, who own Dulcelandia, a local candy and party supply chain. I visited their 26th Street location and met with founders Eduardo and Evalia Rodriguez and their children Marco and Eve. Eduardo and Evalia proudly shared family memories through personal photographs and newspaper articles, showing the growth of their children and their business, which they started in 1995. After scanning photographs, they even gave me delicious guava juice for the road!

Eve and Marco inspecting a candy shipment from Mexico, 1995. Photograph courtesy of the Rodriguez family

Trick-or-treaters lined up in front of Dulcelandia’s Kedzie location for their first Halloween in operation, 1995. Photograph courtesy of the Rodriguez family

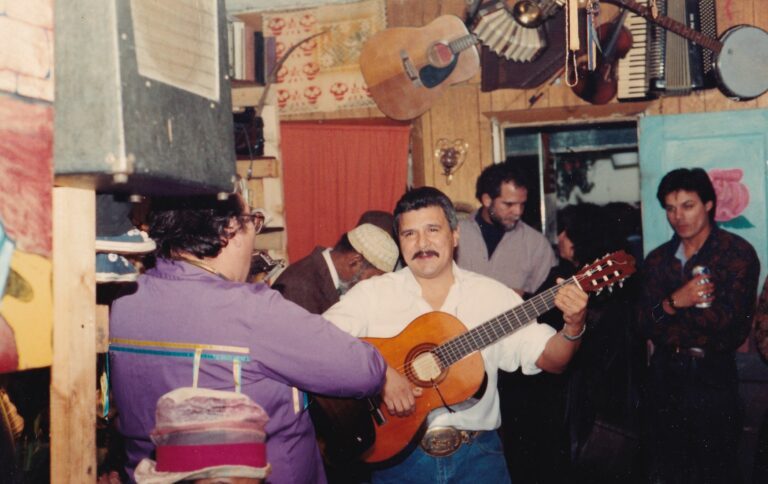

That same day, I visited South Chicago and met with Roman and Maria Villarreal, artists and longtime residents, at their home. Every inch of their home was covered with paintings and sculptures, their own and other’s gifts to these pillars of local Mexican art. Maria searched her archives and found photographs of Roman painting murals, which are no longer on display, friends at old tamale parties, parades, park openings, quinceañeras, baptisms, and other milestones. Maria and Roman are dedicated to creating art, providing a perspective on the community that has seen decades of growth, destruction, and evolution in Chicago. Their hospitality was humbling; they lent me a book and even got tacos for us.

Frank Corona playing the guitar at a tamale party with the late Gamaliel Ramírez in the background, 1980s. Photograph courtesy of Maria and Roman Villarreal

Roman Villarreal painting a mural at the headquarters of the now-defunct Mexican Community Committee of South Chicago, 1980s. Photograph courtesy of Maria and Roman Villarreal

A few weeks later, the Kichwa Community of Chicago enriched the scrapbook with Ecuadorian and Indigenous perspectives. Being of Bolivian and Mexican heritage, I enjoyed learning about familiar ideas and Indigenous practices that I had heard of but knew little about. Both countries have Kichwa/Quechua speakers and were once part of the Tawantinsuyu (Inca Empire). Inti Raymi, the festival for the sun god, Inti, interested me the most. Growing up, I had vague ideas about this festival, knowing the name and some connection to the sun god. It felt was fulfilling to learn about how people dressed as Inti, the festival’s importance, and the water rituals attached to it. After this meeting, I felt more connected to my Bolivian roots and hope to help others feel the same through the Scrapbook.

Members of the Kichwa Community of Chicago dressed in traditional costumes and clothing for Inti Raymi, 2015. Photograph courtesy of the Kichwa Community of Chicago

Working on the Digital Communities’ Scrapbook has been an exciting opportunity to highlight the diversity of Latine Chicago. So far, I have traveled 600+ miles within Chicago, speaking to business owners, politicians, artists, nonprofit workers, and storefront employees. Through this effort, I have borrowed 142 images in addition to those already in the CHM collection. You can help us build this project by sending us your images (versión en español) adding to Chicago’s Latine history.