Latest Posts

CHICAGO (May 30, 2025) – The Chicago History Museum is proud to announce the honorees for the 2025 Making History Awards. This prestigious event celebrates the outstanding achievements of individuals and corporations who have made a lasting impact on the city of Chicago.

Over the past 30 years, we have honored 151 individuals from all walks of life for their enduring contributions to art and culture, sports, business and civic life. We have also celebrated 13 companies for their historic corporate achievements.

The distinguished honorees at the 2025 Making History Awards are:

- Martin Cabrera Jr., CEO & Founder of Cabrera Capital, receiving the Marshall Field Making History Award for Distinction in Corporate Leadership and Innovation

- Susan Crown, Founder and Chairman of the Susan Crown Exchange, receiving the Daniel H. Burnham Making History Award for Distinction in Visionary Leadership

- Hon. Rahm Emanuel, Former U.S. Ambassador to Japan and Former Mayor of the City of Chicago, receiving the Harold Washington Making History Award for Distinction in Public Service

- Steppenwolf Theatre, a Chicago theater company, receiving the Theodore Thomas Making History Award for Distinction in the Performing Arts; Audrey Francis, Artistic Director, and Brooke Flanagan, Executive Director, will accept the award

The award ceremony will take place on Wednesday, June 4, 2025, at 6 p.m. at the Four Seasons Hotel Chicago. Attendees will have the opportunity to hear the unique stories of each honoree and gain insight from their esteemed colleagues on the significance of their contributions to the community. The event will also feature speeches from Chicago History Museum leadership and provide an overview of the Museum’s current initiatives and exhibitions.

The Chicago History Museum inaugurated this event in 1995 to provide vital financial support to the Museum’s operations and programs. More than three decades later, this event is still a cornerstone of the institution, supporting the Museum’s mission to serve as the primary destination for learning, inspiration and civic engagement to connect people to Chicago’s history and each other.

For more information on supporting or attending the Making History Awards, please contact Eric Miller, Development Coordinator, at miller@chicagohistory.org or (312) 799-2110.

The press kit can be found here: https://chicagohistory.box.com/s/ll08hwsf55bzfy6h7zb0jfktqj75bude

###

ABOUT THE CHICAGO HISTORY MUSEUM

The Chicago History Museum is situated on ancestral homelands of the Potawatomi people, who cared for the land until forced out by non-Native settlers. Established in 1856, the Museum is located at 1601 N. Clark Street in Lincoln Park, its third location. A major museum and research center for Chicago and U.S. history, the Chicago History Museum strives to be a destination for learning, inspiration, and civic engagement. Through dynamic exhibitions, tours, publications, special events and programming, the Museum connects people to Chicago’s history and to each other. The Museum collects and preserves millions of artifacts, documents, and images to assist in sharing Chicago stories. The Museum gratefully acknowledges the support of the Chicago Park District on behalf of the people of Chicago.

In Chicago, there are neighborhoods, community areas, and wards, and each term has a distinct meaning. CHM curator of religion and community history Rebekah Coffman explains the differences, why these distinctions exist, and how they change over time, a key theme explored in our upcoming exhibition Aquí en Chicago.

What is a community, and is that the same as a neighborhood? Chicago’s identity as a “city of neighborhoods” implies there would be some way of defining what these neighborhoods are, what that means for Chicagoans living here, and how they create our sense of community. And yet, there are countless ways to think about and draw boundaries around how we could divide and subdivide the city. This could be based on where you live, what businesses you visit, or where your place of work or place of worship is located. It can also be a feeling, somewhere you consider a home, the spaces you walk by every day, the street corners you recognize, where your friends live.

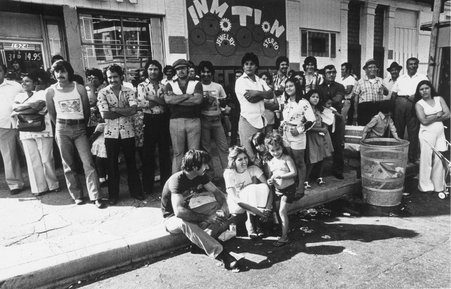

Fiesta del Sol in the Pilsen neighborhood, Chicago, August 1978. CHM, ICHi-031836

When discussing neighborhoods, it is important to think about how there is the idea of a neighborhood, a concept recently re-explored again by the Chicago Neighborhoods Project, and a physical or political boundary used for a specific purpose. In this latter sense, Chicago is often divided in three main ways: neighborhoods, community areas, and wards.

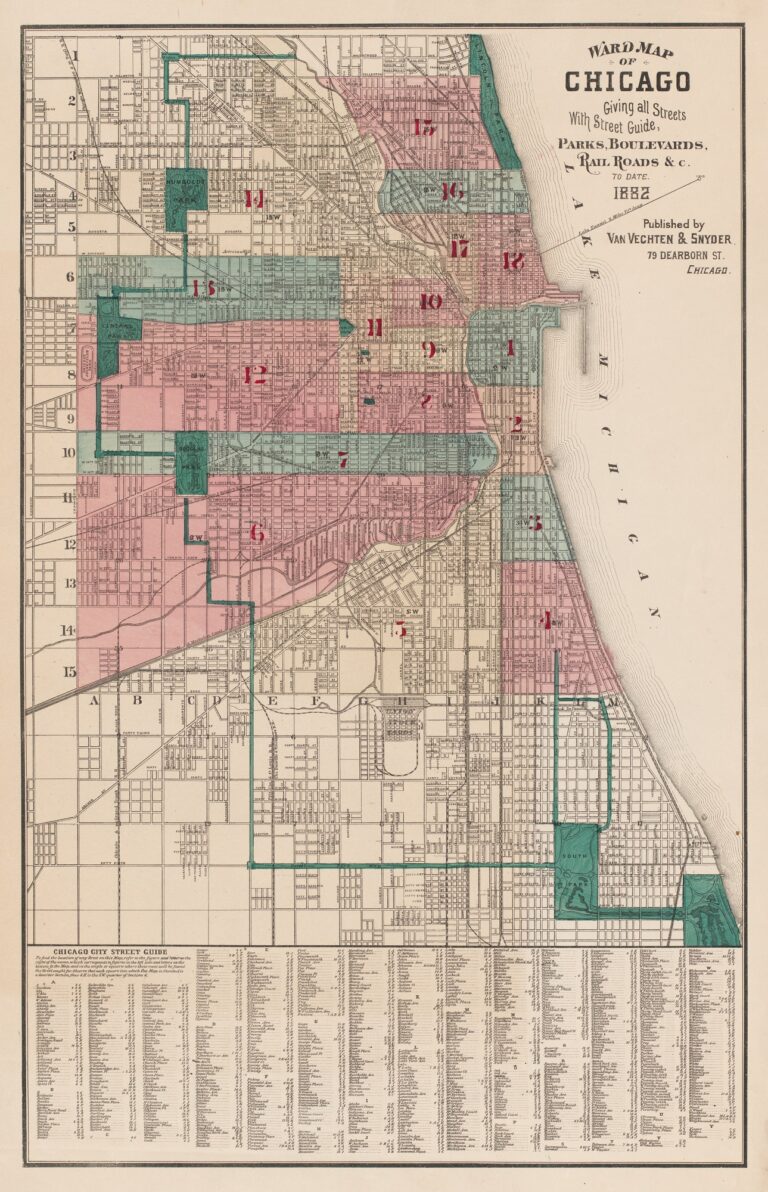

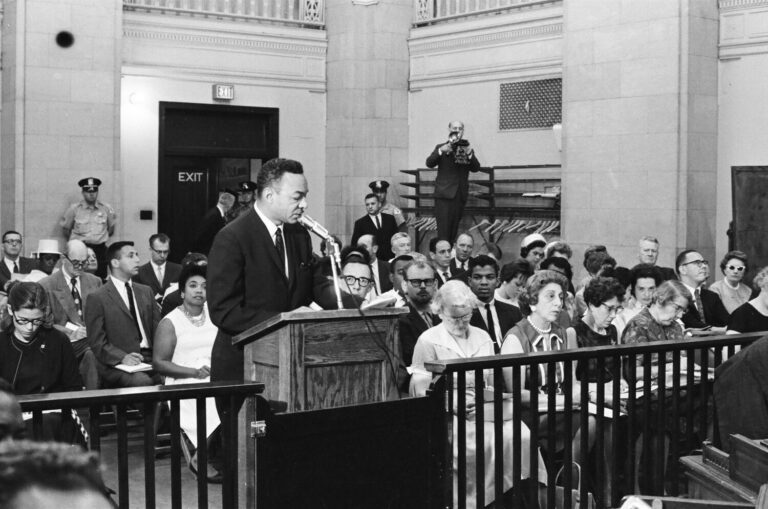

(L) Ward map of the City of Chicago, 1882. CHM, ICHi-092878

(R) Ward map for the City of Chicago, September 19. 1947. CHM, ICHi-173823

Wards relate directly to politics. The City of Chicago is divided into 50 voting districts, or wards, that in turn establish 50 City Council seats. These are meant to be essentially of equal size based on population, with each ward currently holding ~53,900 residents on average. The boundaries of wards can change based on information collected in the census every ten years through a process called redistricting.

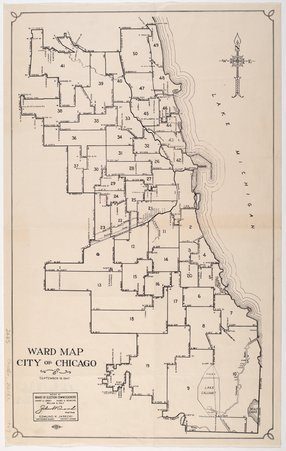

Members of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) speak to the Board of Education on issues of segregation in schools and gerrymandered school district lines. July 30, 1963, ST-60002620-0034, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Redrawing the ward maps can be a fraught and opaque process. For example, new district lines are proposed through an ordinance, which is a verbal description of the locational boundaries proposed, not an actual physical map. Additionally, gerrymandering, or the political manipulation of these boundaries, can create deep inequities by dividing communities into multiple wards making cohesive economic and social stability ongoing challenges.

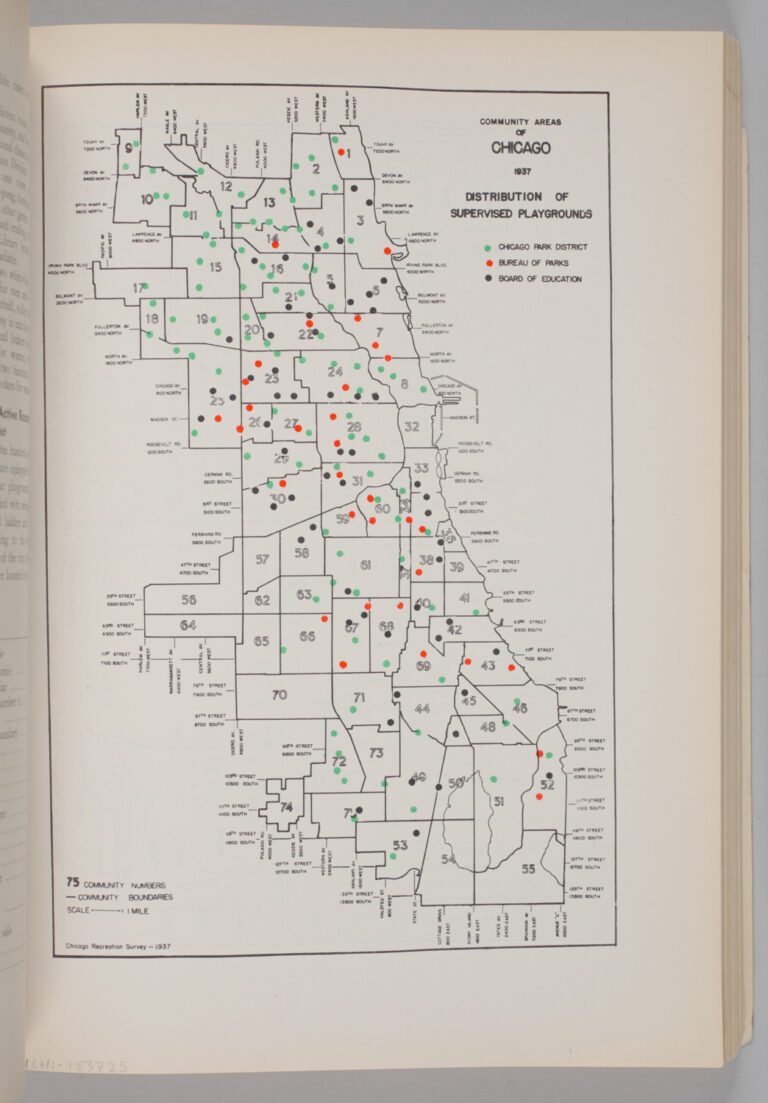

Community Areas of Chicago 1937: Distribution of Supervised Playgrounds, p. 105, 1937. CHM, ICHi-183725; Chicago Recreation Commision, author

When we say communities, as in the opening paragraph above, this can mean a lot of things—be it living in the same place, having similar interests or hobbies, sharing aspects of a cultural identity, and much more. However, “community” in Chicago also refers to the city’s officially defined community areas. Unlike neighborhoods, these are fixed divisions—each having roughly the same population within. In the late 1920s, Robert Park and Ernest Burgess mapped 75 community areas in Chicago based on information from the US Census Bureau, the boundaries for which are still largely unchanged. A small exception is the later additions of O’Hare (1956) and Edgewater (1980) to make the 77 community areas we know and use today. Areas were carefully delineated based on statistics like income, crime rates, and health information. These unchanging boundaries have proved useful for planning and studying purposes.

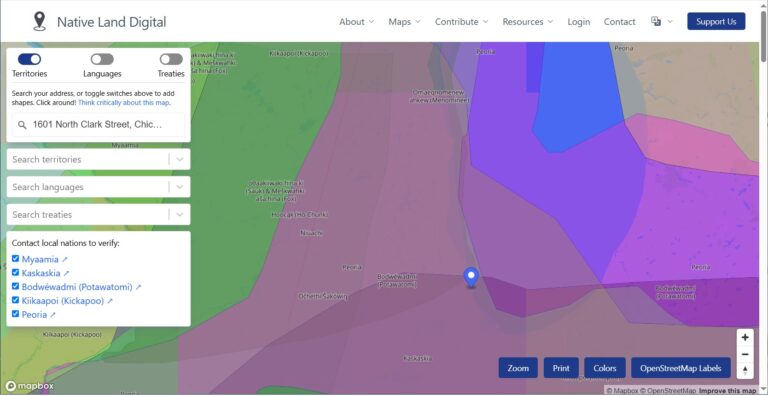

Map data provided by Native Land Digital. Used with permission for educational and non-commercial purposes.

However, they are not a full representation of how Chicagoans perceive the city nor how they define the places in which they live. An “area” is not the same as having a defined space for community or a space of belonging. Additionally, there are countless ways of conceptually thinking of one’s relationship to space and land relationally and fluidly. For example, the Native Land Digital map demonstrates ways to conceive of the Zhegagoynak/Zhigaagon/Zaagawaang/šikaakonki (Chicago) area through language, tribal territories, and treaties in stark contrast to the gridded system we see in most area maps.

A 2021 study on the concept of belonging and cultural institutions importantly notes that people who identify as Black, Latino/a/e, and Asian more often describe community through race or ethnicity, and people who identify as white more often think of community as a place or location. This closely relates to the idea of a “neighborhood,” which is conceptually and practically much more fluid and subjective than a geopolitically defined community area. Neighborhood boundaries and understanding of identity change through time and, for many Chicagoans, drive a stronger sense of place than a community area. Chicago neighborhoods are constantly changing in name and delineation, and today the city boasts more than 200 distinct neighborhoods, each holding claim to a sense of individual identity and local pride.

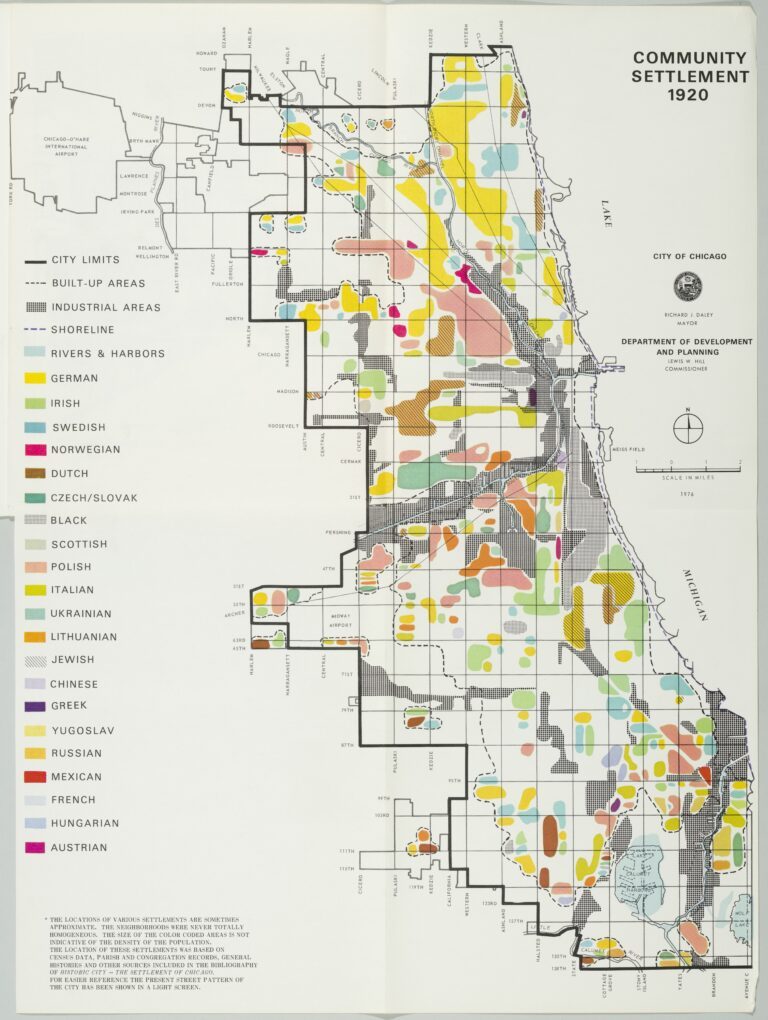

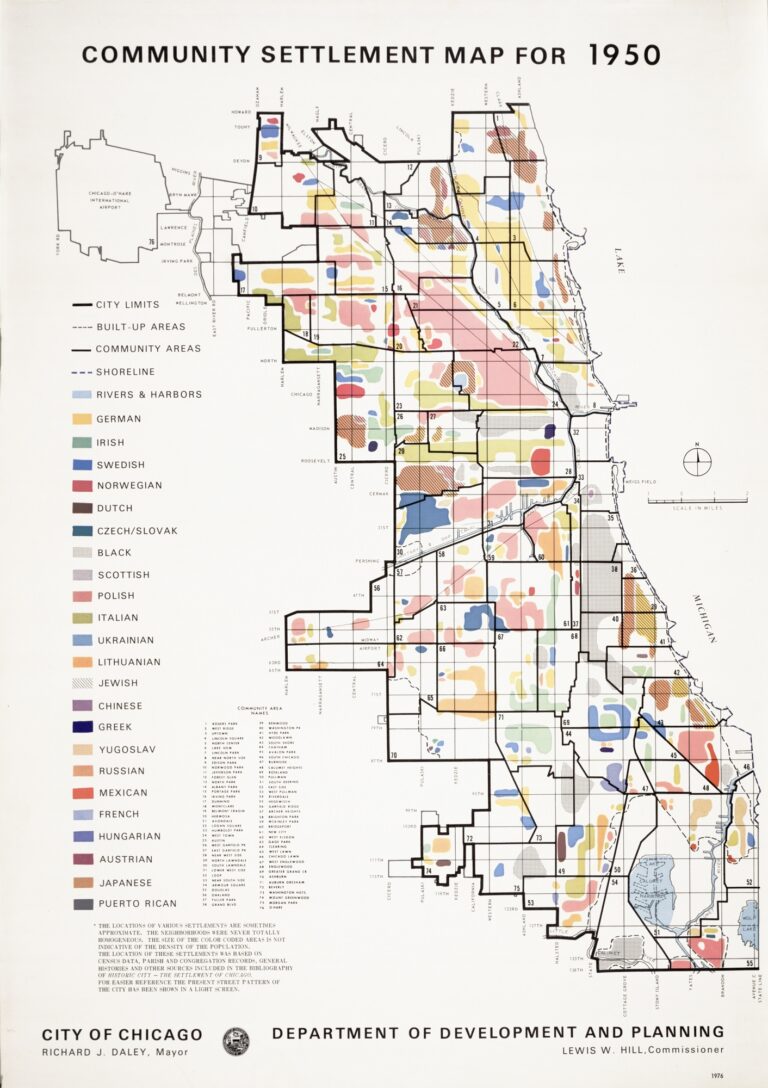

Community Settlement Map for 1920 and 1950 based on race and ethnicity, produced by the City of Chicago Department of Development and Planning, 1976, CHM, ICHi-182192 and ICHi-051194

Seeing Chicago as a city of neighborhoods often goes hand-in-hand with its “multiethnic” identity. This is generally thought of in terms of migration and how communities of different nationalities, ethnicities, races, and languages created space for themselves in the city. Henry C. Binford called this “multicentered Chicago,” arguing that the idea of a “neighborhood” is a vague and contested concept. Instead, Binford claimed we should look at the city as a series of “spatial subcommunities” that have innumerable instances of human interaction and diverse histories.

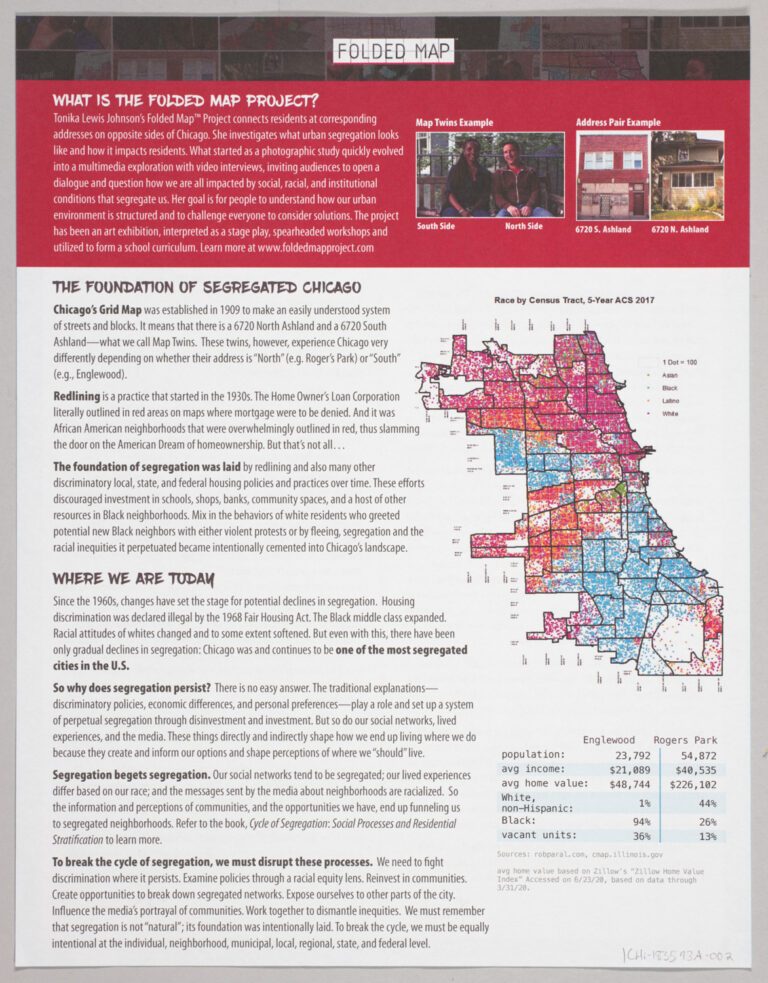

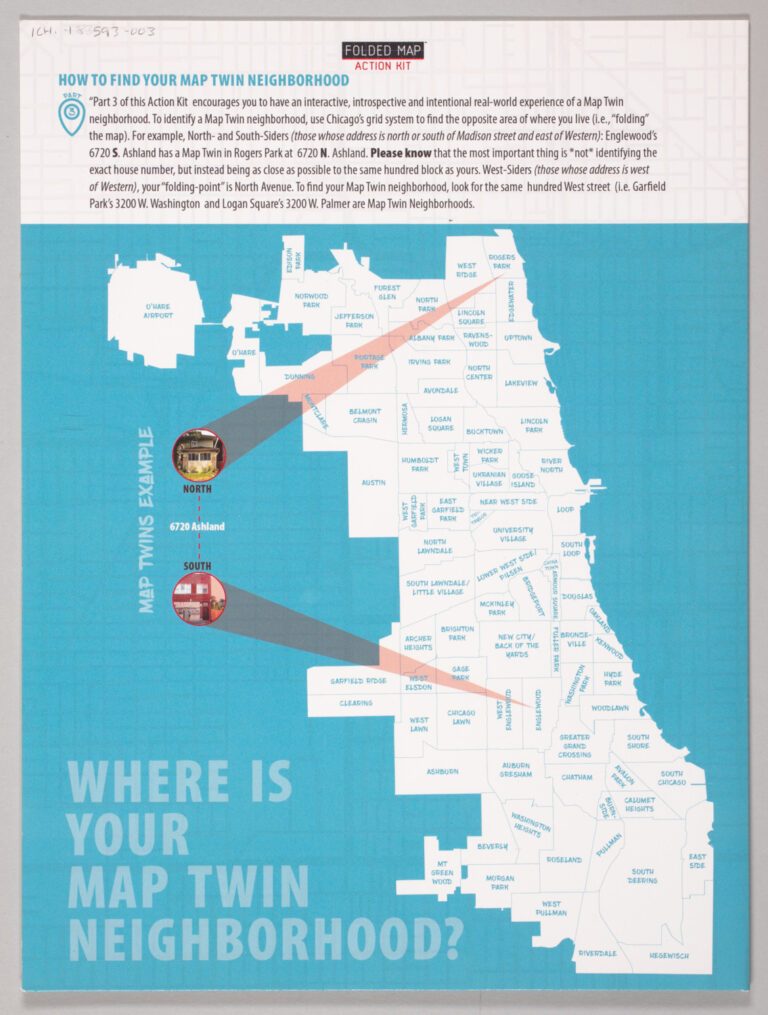

Two pages from the Folded Map Action Kit, a project to connect people living on the North and South Sides of Chicago with each other using the grid street address system to highlight disparities between neighborhoods. Folded Map © 2020, Tonika Lewis Johnson and Maria Krysan. All rights reserved. Kit design by JNJ Creative, LLC; CHM, ICHi-183593A-002, ICHi-183593-003

A related spatial legacy is Chicago’s identity as one of the most segregated cities in the US. In Chicago, segregation has been notably decreasing, and yet it remains the fourth most segregated city in the country, according to data from 2019. These recent studies also show that for many cities across the country, segregation is growing, not declining, with the Midwest disproportionately represented.

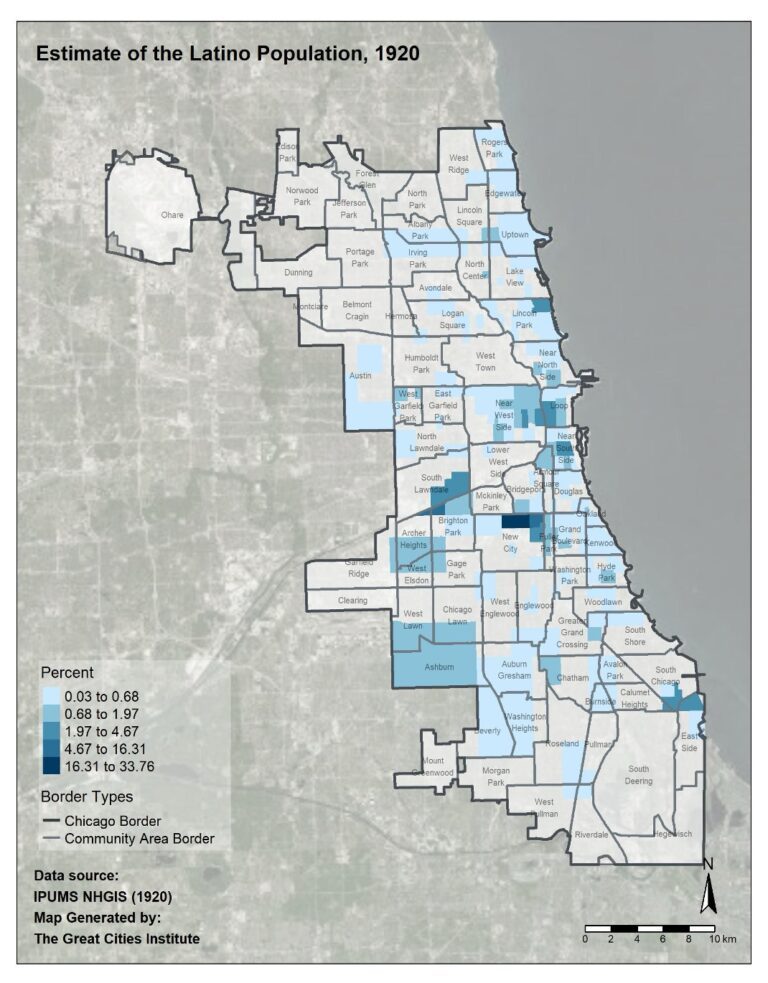

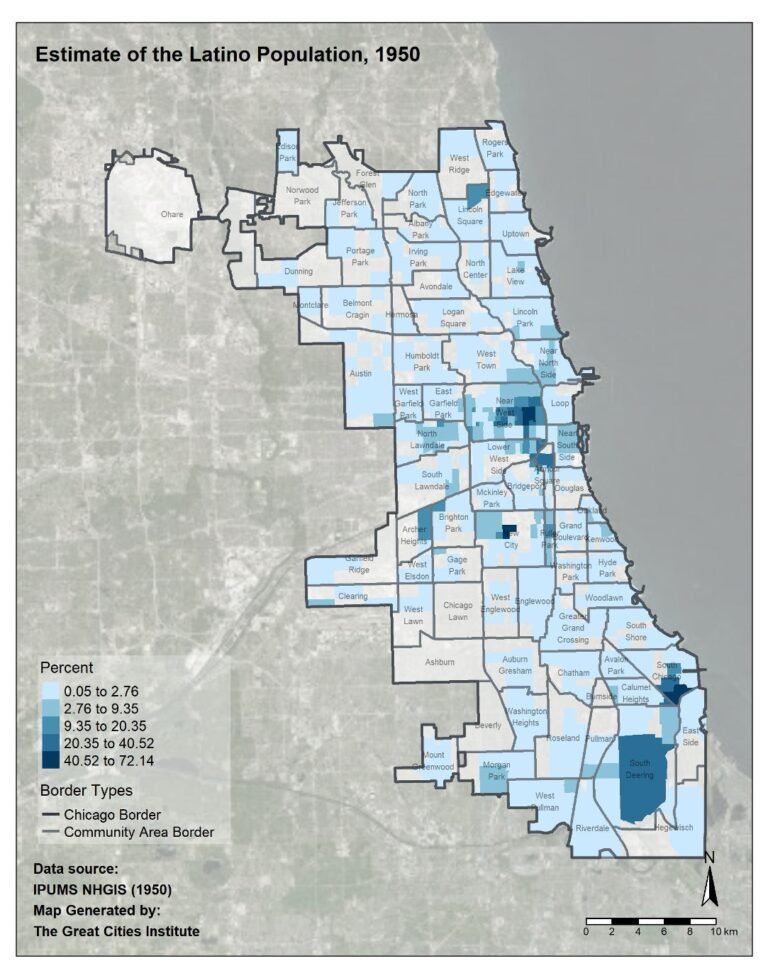

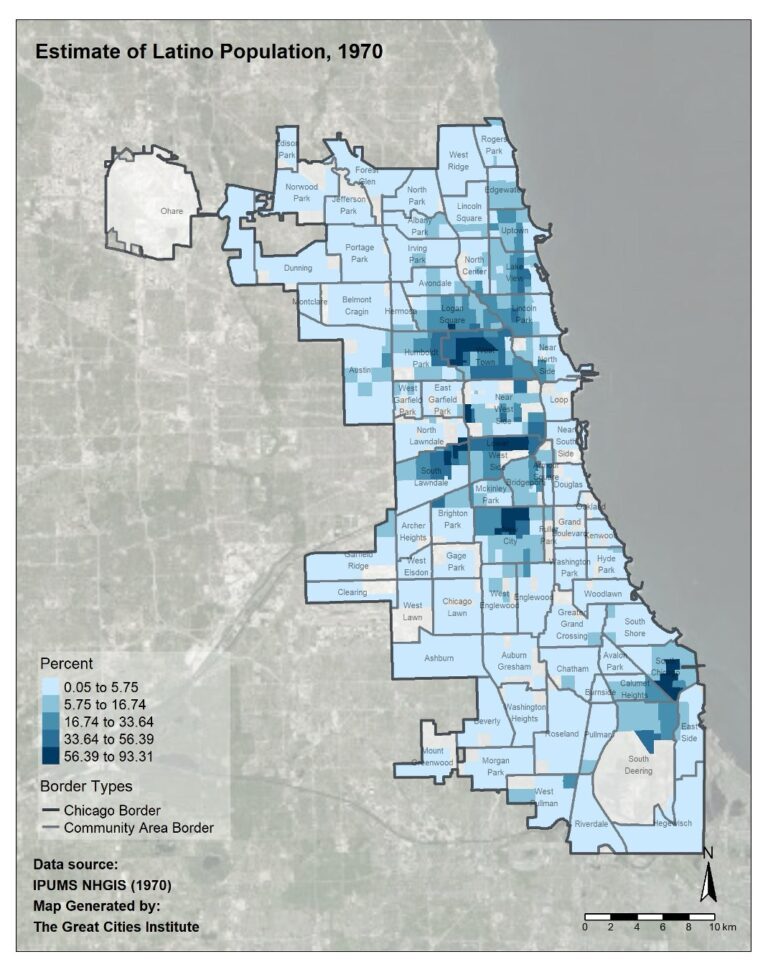

Maps depicting the “Estimate of the Latino Population” in Chicago, 1920, 1950, and 1970. Maps courtesy of Great Cities Institute at University of Illinois Chicago

In the context of Aquí en Chicago, we think about how communities make space for themselves in the city through many ways, including neighborhoods that Latino/a/e communities strongly identify with or have historically called home. These three maps come from a series of maps created by the Great Cities Institute at the University of Illinois Chicago for Aquí en Chicago. They show the demographic distribution of Latino/a/e people across Chicago through time and the evolution of making space from core neighborhoods in the 1920s such as the Southeast Side, Calumet, Back of the Yards, and East Chicago (known as the colonias) to Latino/a/e presence in nearly every part of the city and broader suburban Chicagolandia today.

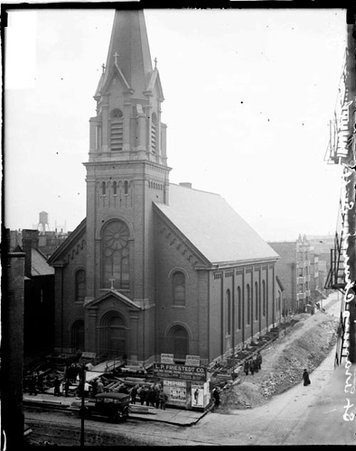

St. Francis of Assisi Catholic Church on the Near West side is an example of ethnic succession, built for the German and German American community and later became Latino/a/e majority in attendance.

(L) St. Francis of Assisi Church, 813 W. Roosevelt Rd., Chicago, 1917. DN-0067872, Chicago Daily News negatives collection, CHM

(R) Exterior view of J. J. Strnad Real Estate with a sign advertising in Spanish and English, 1801 Blue Island Ave., Chicago, January 8, 1961. CHM, ICHi-051411; John McCarthy, photographer

Key to this idea of Latino/a/e neighborhoods is the concept of ethnic succession, in which different ethnic or racial communities occupy different places through time. When we consider evolving neighborhood identities, we see how shifts in elements like who sees themselves as represented in the neighborhood, what are the community anchors, whose image is on the advertisements, and what language is on the business signs, all combine to create a sense of place. That place, that sense of belonging, creates a sense of identity. As this shifts through time, communities, in turn, feel like a sense of ownership may shift as well.

Residents protest the designation of the area around Halsted and Harrison Streets as the site of the new University of Illinois campus, March 19, 1961, ST-17600243, Chicago Sun-Times Collection, CHM

These ethnic shifts do not happen in a vacuum of neutral migration and movement by families and communities. Urban renewal, economic displacement, forced migration, racial segregation, and gentrification are key driving factors for how and why neighborhoods may shift over time. For example, in the 1950s and ’60s, thousands of people were displaced to make way for the Eisenhower Expressway and the University of Chicago Circle Campus. Neighborhoods like Pilsen (as part of the Lower West Side community area) and Little Village (as part of the South Lawndale community area) shifted from being predominantly European residents (in this case, Czech and Polish) to Latino/a/e. Communities make and keep places, in many ways and for many different reasons, defining and making Chicago (and beyond) the city we know today.

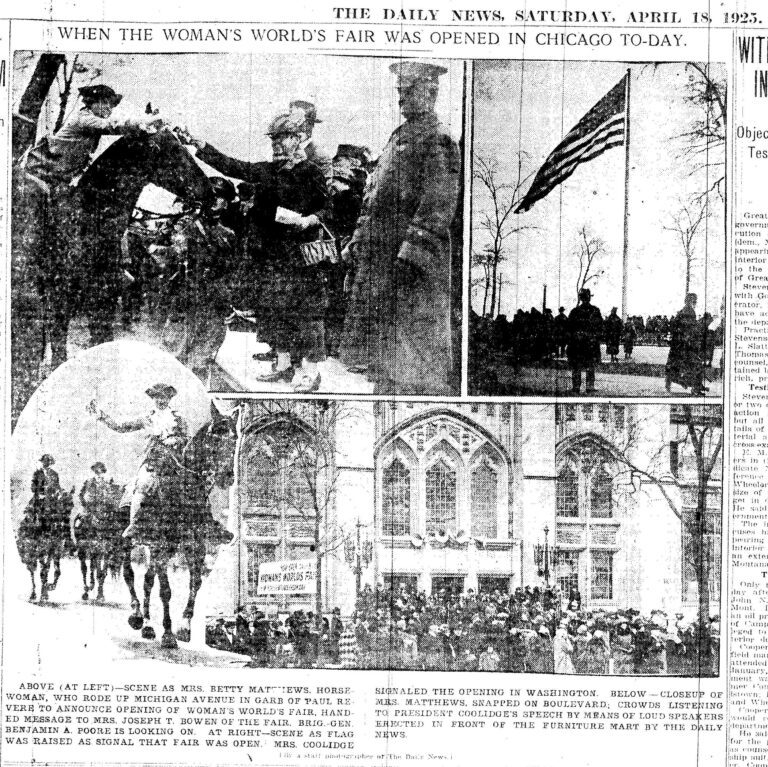

In 1925, the inaugural Woman’s World’s Fair was held April 18–25 in the American Exposition Palace. It attracted more than 160,000 visitors and consisted of 280 booths representing 100 occupations in which women were engaged.

News coverage of the opening showed “Mrs. Betty Matthews, horsewoman, who rode up Michigan Avenue in garb of Paul Revere” on the left, a flag raising that signaled the fair’s opening, and a crowd listening to President Calvin Coolidge’s speech, Chicago Daily News, April 19, 1925, p. 3.

The fair was the idea of Helen Bennett, the manager of the Chicago Collegiate Bureau of Occupations, and Ruth Hanna McCormick, a leading clubwoman and Republican politician.

Cover page of The Woman’s World’s Fair souvenir program, 1925. HQ1106 .W6 1925. CHM, ICHi-037941

It was, in part, inspired by the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition and initiatives such as the Woman’s Building. However, it was also a response to the unequal representation and lack of visibility some women experienced in 1893. Women organizers publicized and ran the fair; its managers and board of directors were all women.

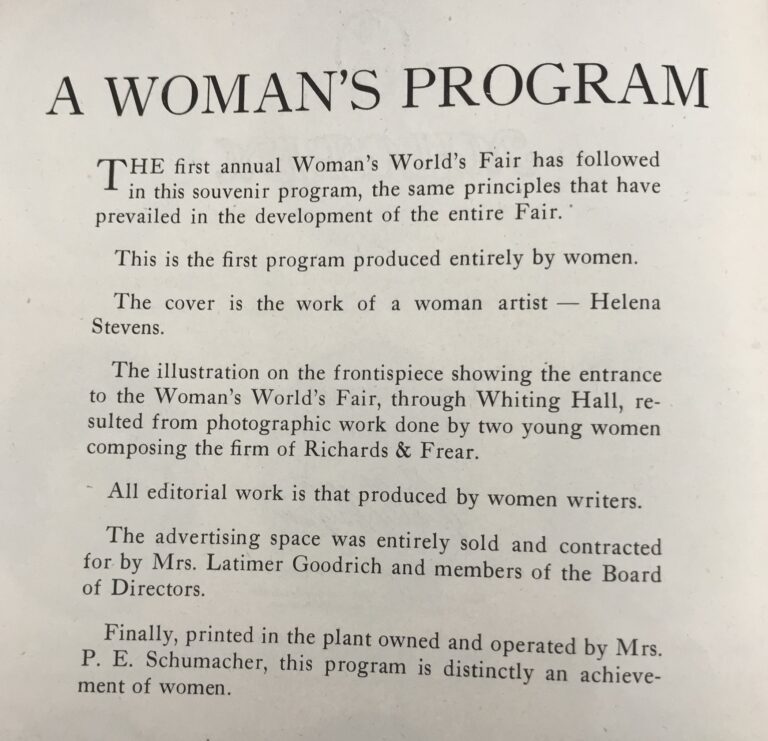

The souvenir program was also entirely produced by women. Photograph by CHM staff

The fair had the double purpose of displaying women’s ideas, work, and products, and raising funds to help support women’s Republican Party organizations. The booths at the fair showed women’s accomplishments in the arts, literature, science, and industry. These exhibits were also intended as a source for young women seeking information on careers.

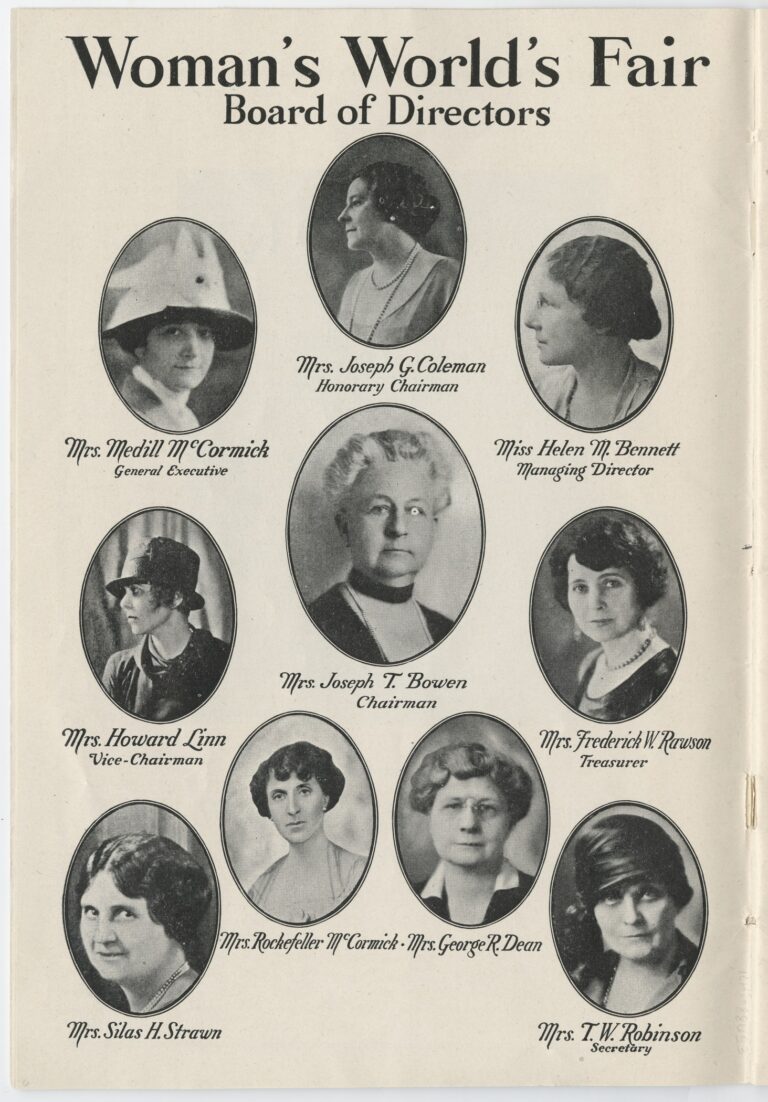

Portraits featuring the Woman’s World’s Fair Board of Directors from page 6 of The Woman’s World’s Fair souvenir program, 1925. HQ1106 .W6 1925. CHM, ICHi-088653

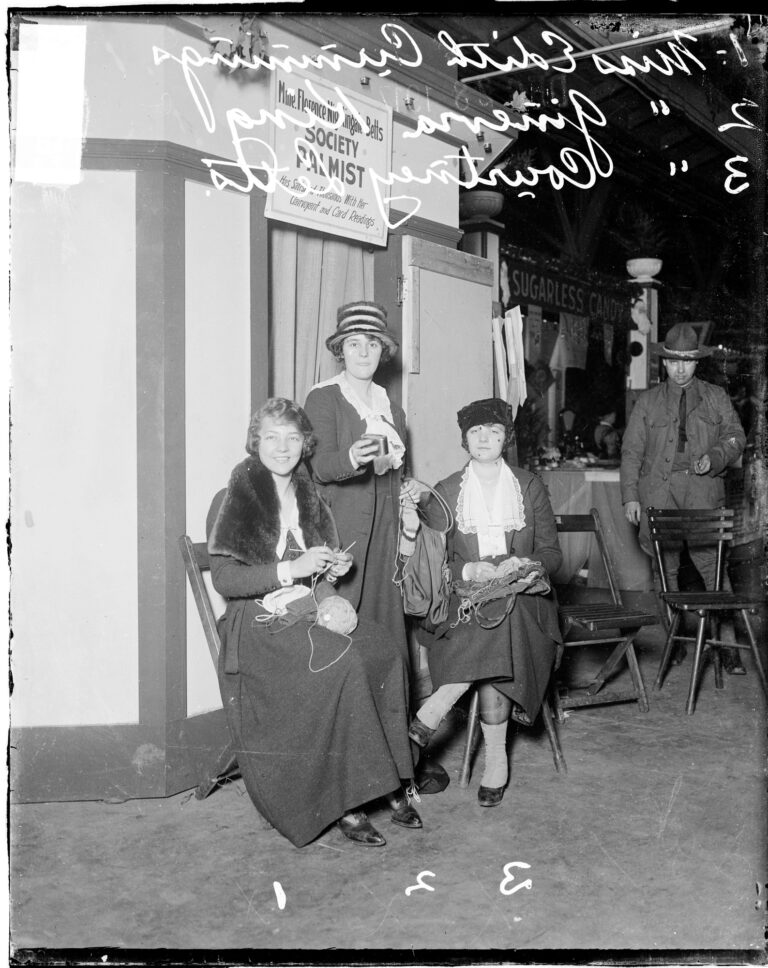

Among the exhibitors at the fair were major corporations, such as Illinois Bell Telephone Company and the major national and regional newspapers. Local manufacturers, banks, stores, and shops, area hospitals, and women inventors, artists, and lawyers set up booths demonstrating women’s contributions in these fields and possibilities for employment. Women’s groups were represented by such organizations as the Women’s Trade Union League, Business and Professional Women’s Club, the Visiting Nurse Association, the YWCA, Hull-House, the Illinois Club for Catholic Women, and the Auxiliary House of the Good Shepherd.

From left, seated: Mrs. Joseph T. Bowen, Gov. Nellie Tayloe Ross, Judge Katherine Sellers, Cyrena Van Gordon, Dr. Helen M. Strong. From left, standing: Mrs. Radford Warren, Mrs. Mabel Reinecke, Miss Lucia Briggs, Fannie Ferber Fox, Paulina Palmer, Mrs. Lois Pierce Hughes, Chicago Daily News, April 24, 1925, p. 5.

The 1925 fair raised $50,000 and was so successful that it was held for three more years.

It should be noted that the Woman’s World’s Fair of 1925 came in the wake of two major events. In the summer of 1919, tensions in the city were high after the racially motivated drowning of Eugene Williams, an African American teenager, in Lake Michigan and ensuing violence and deaths of both Euro-American and African American Chicagoans.

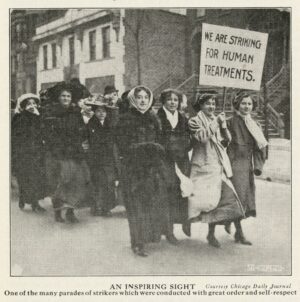

That same year, the US Congress passed the 19th Amendment, giving women the right to vote. The suffragist movement also saw racial tensions, as white organizers would exclude or segregate African American and other women of color from their marches and other efforts. Nevertheless, the resolution’s ratification in 1920 became a watershed moment for women’s rights and radically shifted the national political climate forever.

On the one hand, women asserted their right to be recognized and uplifted through dedicated events of their design. On the other hand, while some strides were made in more racially diverse representation, inequality persisted.

Additional Resources

- View our online exhibition Democracy Limited: Chicago Women & the Vote, which invites visitors to explore women’s activism in Chicago to secure the right to vote—and beyond.

- Listen to Studs Terkel’s interviews with many of the leading advocates of feminism and women’s rights in the mid to late 20th century.

- Peruse our Women’s Studies LibGuide, which lists research collections in the Abakanowicz Research Center relating to women, both within the greater Chicago area and within the broader context of the US.

CHICAGO (April 16, 2025) – The Chicago History Museum is thrilled to announce it has extended the run of its exhibition “Designing for Change: Chicago Protest Art of the 1960s–70s.” Opened on May 18, 2024, the exhibition will now be on display through November 2, 2025. Made possible in part by the generous support of the Terra Foundation for American Art, “Designing for Change” is a dynamic experience that transports visitors back to a pivotal time in Chicago and U.S. history and connects that era to issues of the present. Through the lens of protest art, visitors gain a deeper understanding of one of the most tumultuous periods in U.S. history, how it continues to shape our world today and the role that art played in advocating for change.

The exhibition features more than 100 thought-provoking artifacts, including posters, fliers, signs, banners, newspapers, magazines and books from the 1960s and ’70s. These expressive works convey the often-radical ideas regarding race, war, gender equality and sexuality that challenged the social norms of the time. The exhibition also features period photography and first-person interviews delving deeper into Chicago’s tradition of activist art, now called “artivism.” A concluding section features works by a new generation of artivists who are carrying on Chicago’s rich legacy of protest art in response to critical issues of our time.

When asked about the significance of the exhibition, curator Olivia Mahoney said, “Chicago artists helped change the world by creating powerful signs, symbols and imagery for the Civil Rights, Black Power, anti-Vietnam War, women’s liberation and early LGBTQIA+ movements. We hope the exhibition will remind visitors of the critical role that free expression plays in a democratic society, and that it will inspire them to become more involved in civic affairs and work for positive change.”

The Chicago History Museum invites the public to explore the profound impact of protest art and its ability to shape society. Don’t miss this opportunity to witness the transformative power of design and be inspired to create positive change.

For more information, please visit the Chicago History Museum’s website or contact the Museum’s press office. Media kit available here: https://app.box.com/s/supm186ynm62k12js889jqtpi1ibkkwz

###

ABOUT THE CHICAGO HISTORY MUSEUM

The Chicago History Museum is situated on ancestral homelands of the Potawatomi people, who cared for the land until forced out by non-Native settlers. Established in 1856, the Museum is located at 1601 N. Clark Street in Lincoln Park, its third location. A major museum and research center for Chicago and U.S. history, the Chicago History Museum strives to be a destination for learning, inspiration, and civic engagement. Through dynamic exhibitions, tours, publications, special events and programming, the Museum connects people to Chicago’s history and to each other. The Museum collects and preserves millions of artifacts, documents, and images to assist in sharing Chicago stories. The Museum gratefully acknowledges the support of the Chicago Park District on behalf of the people of Chicago.

Tornadoes and severe storms are no stranger to the Chicago area.

Clean-up work being done in Lemont, Illinois, after a tornado came through the area on March 27, 1991. ST-11002137-0015, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Since the 1960s, tornadoes have occurred more frequently in the far western and southwestern suburbs in a corridor from Aurora to Joliet and south toward Kankakee. However, tornadoes can occur anywhere in the Chicago area—including inside the city limits. Just last year, on July 15, 2024, a tornado touched down along I-290 and crossed the river into downtown Chicago.

Tornado damage at the Marycrest shopping center in Joliet, Illinois, April 6, 1972. Carnival equipment in the parking lot was blown into the MFA Insurance Agency. ST-17303614-0036, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

According to the National Weather Service (NWS), in the Chicago area, tornadoes are most common in spring, with a secondary peak in late summer to mid-fall. They most frequently occur in the afternoon and evening, with the peak between 5 and 6 p.m. When the conditions are favorable for tornado formation, sometimes several significant tornadoes occur in the same area on the same day.

Scenes of the damage sustained in Oak Lawn from a tornado that struck on April 21, 1967, including an upturned trailer at 91st and Cicero Ave., milk bottles that survived a restaurant being leveled, transit buses thrown across the street from the company, and aerial helicopter footage. ST-17302102-0008, ST-17302007-0052, ST-17302007-0058, ST-17301778-0017, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

On April 21, 1967, five significant tornadoes struck the area. An F4 tornado (on the Fujita scale, or F scale, an F4 tornado’s winds are estimated to have been 207–260 mph) formed in Palos Hills in Cook County and traveled through Oak Lawn and then across the South Side of the city, hitting the lakefront near 79th Street. The 200-yard-wide tornado traveled 16 miles and caused the deaths of 58 people (33 in Cook County) and over $50 million in property damage.

Tornado damage in a residential area of Lemont on June 13, 1976. ST-40003570-0010, ST-40003570-0029, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Another notable tornado struck on June 13, 1976, looping through the Lemont area. While on average tornadoes are on the ground for five minutes, this tornado remained on the ground for over an hour, causing $13 million of destruction and killing 2 people. The tornado was also unusual in that it stayed stationary for a period. Its total track was 8 miles long with a width of up to 800 yards.

Clean-up in Plainfield after the tornado, including members of the Mennonite community, September 4, 1990. ST-14000070-0027, ST-14000070-0013, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

The only F5 tornado (estimated winds of 261–318 mph) to strike Chicago struck Plainfield on August 28, 1990. It is the only F5 tornado ever officially recorded in August in the United States. The tornado formed near Oswego and took an unusual southeasterly path through Plainfield, Crest Hill, and Joliet. On its 16-mile-long path, the tornado killed 29 people, injured another 350, and caused $165 million in damage. Forecasters gave little warning time for the tornado, and ultimately the event led to changes in forecasting.

To mark the first anniversary of the tornado that devastated the village, Plainfield residents gathered for fellowship on August 25, 1991. ST-10000107-0013, Chicago Sun-Times collection CHM

At the time of the Plainfield tornado, the Chicago office of the NWS was responsible for providing forecasts for the entire state of Illinois. After the tornado, the NWS created two new offices—Romeoville in 1993 and Lincoln in 1995—to reduce the Chicago office’s workload. Tornado forecasting has also improved since 1990 with the installation of NEXRAD, a network of high-resolution weather radars, which has also undergone several technological advances to better track and anticipate dangerous severe weather and tornadoes.

Have you experienced a tornado in the area?

Additional Resources

- Search and Browse photographs at CHM Images

- Find more images from CHM’s Chicago Sun-Times collection

- Read the entry on tornadoes in the Encyclopedia of Chicago

- Learn more about University of Chicago scholar Ted Fujita, who reshaped what we know about tornadoes

To mark the centennial of the publication of The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald (1896–1940), CHM director of exhibitions Paul Durica writes about the novel’s many connections to Chicago.

Like the green light at the end of Tom Buchanan’s dock, the city of Chicago remains present yet out of reach throughout the text of The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s classic novel that turns 100 this year.

Chicago is where Buchanan is from, the source of his family’s vast wealth. The “string of polo ponies” on his East Coast estate hails from Lake Forest, located about 27 miles north of the Loop. Chicago is where he and his wife Daisy, originally from Louisville, lived before their move to Long Island. The first thing she asks her “second cousin once removed,” Nick Carraway, the novel’s narrator, is if people miss her in Chicago. “The whole town is desolate,” he replies. “[T]here’s a persistent wail all night along the North Shore.”

Buchanan money is old money, at least by Chicago standards. The novel’s title character Jay Gatsby depends upon the city for his wealth as well, albeit from more illegal sources.

When Nick first meets his neighbor Gatsby at one of the latter’s lavish parties, he quickly excuses himself upon learning that “Chicago was calling him on the wire,” presumably in connection with his bootlegging ventures. Later, Nick meets one of Gatsby’s associates, the gambler Meyer Wolfshiem, casually identified as the “man who fixed the World’s [sic] Series back in 1919,” the one involving the Chicago “Black Sox.”

All these references to Chicago in a novel set entirely in New York are intentional. For Fitzgerald, Chicago is both the gateway and stand-in for the greater Midwest. Late in the novel, Nick remembers train trips “coming back west from prep school and later from college at Christmas time.” These trips always involved a stopover in the “old dim Union Station” in Chicago where those staying would exchange some “holiday gayeties” with those continuing on. It was only after leaving Chicago that Nick experienced the “winter night and the real snow, our snow” as the “dim lights of small Wisconsin stations” passed by the train’s windows. This landscape he regards as “my middle west.”

Exterior view of the old and new Union Station buildings seen from the Monroe Street Bridge, Chicago, 1925. A Pennsylvania Railroad train is passing in the foreground. CHM, ICHi-073561

“I see now that this has been a story of the West, after all,” Nick muses, in the aftermath of Gatsby’s murder, brought about by his failed dream of reclaiming his lost love, Daisy. “Tom and Gatsby, Daisy and Jordan and I, were all Westerners, and perhaps we possessed some deficiency in common which made us subtly unadaptable to Eastern life.”

The public lives of the Chicagoans who served as the models for the golfer Jordan Baker, as well as Tom and Daisy Buchanan, suggest they didn’t share the “deficiency” of their fictional counterparts.

From left: Alexa Sterling, a golfer, with Edith, D. N., and Adrian Cummings, standing in front of a tent at the Onwentsia Country Club, Lake Forest, Illinois, November 1915. Edith Cummings defeated Stirling for the 1923 women’s amateur title in Rye, New York. DN-0065346, Chicago Daily News Collection, CHM

Charles Scribner’s Sons published The Great Gatsby on April 10, 1925. The following day the society page in The Chicago Daily Tribune shared that Edith Cummings would not be “going to England this spring to compete with our neighbors over the sea in the British golf tournament,” as had been rumored, but would be staying in Chicago.

From left: Edith Cummings, Gineva King (standing), and Courtney Letts at an event for the Christmas Fund for French Children, Chicago, 1917. DN-0069439, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

Edith Cummings (1899–1984) was the model for Daisy’s friend and Nick’s romantic interest, Jordan Baker. Like Baker, she was young, from a prominent family, and known for her athleticism. In 1923, she came from behind to win the women’s amateur golf title at Rye, New York. Her success as a golfer landed her on the cover of Time. She was an avid skier as well and would play a small part in fellow Chicagoans Walter and Elizabeth Paepcke falling in love with an old mining town in Colorado, known for its excellent slopes, which they’d transform into a premier resort and center of intellectualism, Aspen.

That same society column from April 10 mentions one of Cummings’s closest friends, “Mrs. William H. Mitchell.” She was among “four of society’s fairest” who’d been chosen to “model for Vogue at the Woman’s World’s Fair,” opening the following week. As was the convention in 1925, “Mrs. William H. Mitchell,” was identified by her husband’s name. They had married in 1918, in a service held at St. Chrysostom’s Episcopal Church, on Dearborn Street, a short walk from the Chicago History Museum.

Wedding portrait of William H. Mitchell and Ginevra King Mitchell, c. 1918. CHM, ICHi-054512

William H. Mitchell (1895–1987) was the model for the polo-playing Tom Buchanan. He came from a respected family of bankers. His public life was punctuated with moments of drama and tragedy fit for a novel. Mitchell served with distinction as an aviator in World War I. About a decade after his marriage and two years after the publication of Gatsby, he lost his parents in an automobile accident. His father, who’d played an important role in shaping the Federal Reserve, left his son with the very Tom Buchanan-appropriate advice that “success comes to the man who engages in business as in a game, because he is interested enough to play hard.” Mitchell and his wife lived in a mansion in Lake Forest, where in 1931, they and several guests were robbed of money and jewelry at gunpoint by a gang of thieves. When the latter were brought to trial, public sympathy seemed more with them than with the Mitchells, who’d maintained their wealth during the Great Depression.

William H. Mitchell standing next to an airplane that is resting on sawhorses, Chicago, 1917. DN-0069247, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

By that time, Mitchell’s marriage was faltering. His wife, Ginevra King (1898–1980), would ultimately leave him. King has the strongest connection to Gatsby, being the inspiration, as acknowledged by Fitzgerald himself, of Daisy Buchanan. As Daisy was for Gatsby, Ginevra King was the great, unobtainable love of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s life.

Ginevra King Mitchell (Mrs. William H. Mitchell) wearing a gown and a large headdress, Chicago, 1922. DN-0075229, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

She came from old Chicago money and was raised on Astor Street and in Lake Forest. Like her good friend and bridesmaid Edith Cummings, King was admired for her athleticism but also for her volunteerism. She met Fitzgerald at age 16 when he was back in his native St. Paul, Minnesota, on holiday from Princeton University. The two continued to write to one another upon returning to their respective schools on the East Coast, and the 18-year-old Fitzgerald even traveled to Lake Forest to continue courting her. A strong emotional bond, particularly on the part of the aspiring writer, seemed to have formed, but marriage to one of wealthiest debutantes in Chicago was out of the question for this upper-middle-class Midwesterner. As someone, sometimes identified as Charles Garfield King, Ginevra’s father, told him, “Poor boys shouldn’t think of marrying rich girls.”

World War I profoundly impacted their lives, with a distraught Fitzgerald signing up to serve in the military and King doing what she could to support the soldiers on the home front. Afterward, they each found themselves in complicated marriages, with Fitzgerald wedding Zelda Sayre to whom he dedicated Gatsby.

Decades later, King and Fitzgerald reunited briefly in Hollywood, where the novelist was attempting to make it as a screenwriter. She apparently asked him which of his characters she’d inspired. An intoxicated Fitzgerald demeaned her in his response. King later married John T. Pirie Jr., heir to a department store fortune. Fitzgerald died in Hollywood in 1940 at the age of 44.

Ginevra King Pirie died at the age of 82 in 1980. Her Chicago Tribune obituary mentioned her work as president of the Service Club of Chicago and leadership with the American Cancer Society. It does not mention that this Chicagoan was the inspiration for one of the great characters in American literature.

Sources

Borrelli, Christopher, “Real Daisy Bloomed on Chicago’s North Shore,” Chicago Tribune, May 7, 2013: C1.

“Extending Birthday Greetings to Two of Our Leading Citizens,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 11, 1925: 19.

Fitzgerald, F. Scott. The Great Gatsby. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1925.

“J.J. Mitchell’s Rules for Life Are Told by Son,” Chicago Daily Tribune, November 4, 1927: 19.

“Miss Cummings is New Golf Queen,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 7, 1923: A1.

“Mitchell Gem Gang Guilty,” Chicago Daily Tribune, January 17, 1932: 1.

“Obituaries,” Chicago Tribune, December 14, 1980: B27.

“Seize 3; Find $150,000 in Loot,” Chicago Daily Tribune, November 23, 1931: 1.

Thalia, “Chicagoans Live on Ranch in Colorado,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 4, 1946: F1.

CHICAGO (February 13, 2025) – The Chicago History Museum has received a $50,000 donation from the Joseph N. & Rosemary E. Low Foundation. The gift was made possible by Chicago History Museum Trustee John Low and his wife Barbara Low, who made the donation in memory of John’s mother, Wilma V. Low, a proud member of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi.

Michael Anderson, Vice President of External Relations and Development thanked the Lows and noted their longtime support of the work of the Chicago History Museum.

“John Low has not only given of this time as a Trustee to the Museum, he is also a scholar, teacher and lifetime advocate on behalf of indigenous people in Chicago and the Midwest,” Anderson noted, “we are grateful to John and Barbara, and the Low Foundation, for their friendship, dedication and support of our efforts at the Chicago History Museum.”

John Low noted that the gift had a special meaning because it was given in recognition of his mother.

“On behalf of the Low Foundation, Babara and I are honored to make this donation to the Chicago History Museum in memory of my mother,” trustee Low noted. “Wilma was a person who loved history, the power of museums to educate and illuminate, and our family trips to the museums in Chicago, including the CHM. She would be so proud the Foundation is helping to support the Chicago History Museum.”

As a member of the Potawatomi Pokagon Band, Low has researched and written a seminal book about the local Potawatomi history entitled Imprints: The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians and the City of Chicago. He continues to give lectures and work with local organizations to help people understand and recognize the history, language and culture of Chicago’s first inhabitants – whose descendants continue to be a part of our city today.

In addition to his role as Professor of Comparative Studies at the American Indian Studies department at The Ohio State University, John Low is Director of the University’s Newark Earthworks Center, where he works with students, scholars and indigenous people to protect and understand this Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks UNESCO World Heritage Site – as well as to study and preserve other important sites throughout the Midwest.

Last July, Low donated a letter to the Museum archives that was handwritten by Potawatomi leader Simon Pokagon in 1898. An outspoken and sometimes controversial leader, Pokagon met with President Abraham Lincoln to lobby for return of native lands and was a featured speaker at the 1893 Chicago Columbian Exposition.

The letter is important because it gives clues to a long-standing debate about the authorship of the book “O-gi-waw-kwe Mit-i-gwa-ki,” or “Queen of the Woods,” which was published in 1899 shortly after Simon’s death. The popular romantic novel tells the story of Simon’s wife, Lodinaw and earned Pokagon the moniker “the Red Man’s Longfellow” by literary fans at the turn of the century.

Michael Anderson thanked the Lows for the foundation’s ongoing support of the Museum and its mission.

“In addition to another recent generous gift from the Low Foundation,” Anderson noted, “this gift helps us fulfill the mission of the Chicago History Museum – which is to be the primary destination for learning and inspiration, connecting people to Chicago and each other. We are grateful to have trustees and friends like the Lows who are a part of the effort to make this goal a reality.

###

ABOUT THE CHICAGO HISTORY MUSEUM

The Chicago History Museum is situated on ancestral homelands of the Potawatomi people, who cared for the land until forced out by non-Native settlers. Established in 1856, the Museum is located at 1601 N. Clark Street in Lincoln Park, its third location. A major museum and research center for Chicago and U.S. history, the Chicago History Museum strives to be a destination for learning, inspiration, and civic engagement. Through dynamic exhibitions, tours, publications, special events and programming, the Museum connects people to Chicago’s history and to each other. The Museum collects and preserves millions of artifacts, documents, and images to assist in sharing Chicago stories. The Museum gratefully acknowledges the support of the Chicago Park District on behalf of the people of Chicago.

This year, Punxsutawney Phil saw his shadow on Groundhog Day, which (supposedly) means six more weeks of having to wear your winter coat. In this blog post, CHM costume collection intern Grace Koehler writes about a winter coat that represents retail, manufacturing, and fashion history.

At the turn of the 20th century, department stores played an important role in the economies of urban areas, especially Chicago. These stores originated in Europe and began cropping up in the United States during the 1830s. By the end of the century, they played a unique role in that both their target market and main workforce consisted of women. With the emergence of a middle class brought about by the Industrial Revolution making luxury goods and services more affordable, more women were able to stay home and maintain the household, relying on their husbands to provide. The new industries also enlisted the help of women as workers, and the idea of a woman having a job outside the home also became more acceptable. The department store offered employment for unwed women looking for a relatively “respectable” job in the city and offered a place to spend time (and money) for the married lady with a working husband and a disposable income.

Pedestrians viewing a Marshall Field & Company department store window display in the Loop community area of Chicago, 1910. DN-0008625, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

These stores offered a variety of goods at an unprecedented scale, especially ready-made clothing in fashionable styles for lower prices than those custom made for the wearer. These ready-to-wear garments in department stores and catalogues allowed more people access to rapidly changing styles, or at the very least offered them a chance to replace their worn-out wardrobes. Unlike today, however, the quality and attention to detail on these items was reduced relatively little compared to their bespoke counterparts. Though prices for these clothes were still higher than the cheap price tags on today’s fast-fashion items, those who made the clothing were similarly underpaid and overworked.

Garment workers on strike, Chicago, 1911. CHM, ICHi-067059

Instead of sourcing labor overseas as is common now, factories employed local working-class women and children, particularly immigrants. Unlike the women working in the department stores, these workers faced harsher conditions and rampant exploitation, particularly since unions and child labor laws were only just coming into play. They must have been efficient and highly skilled to have produced such quality goods at the rate needed to keep up with mass production and consumer demand.

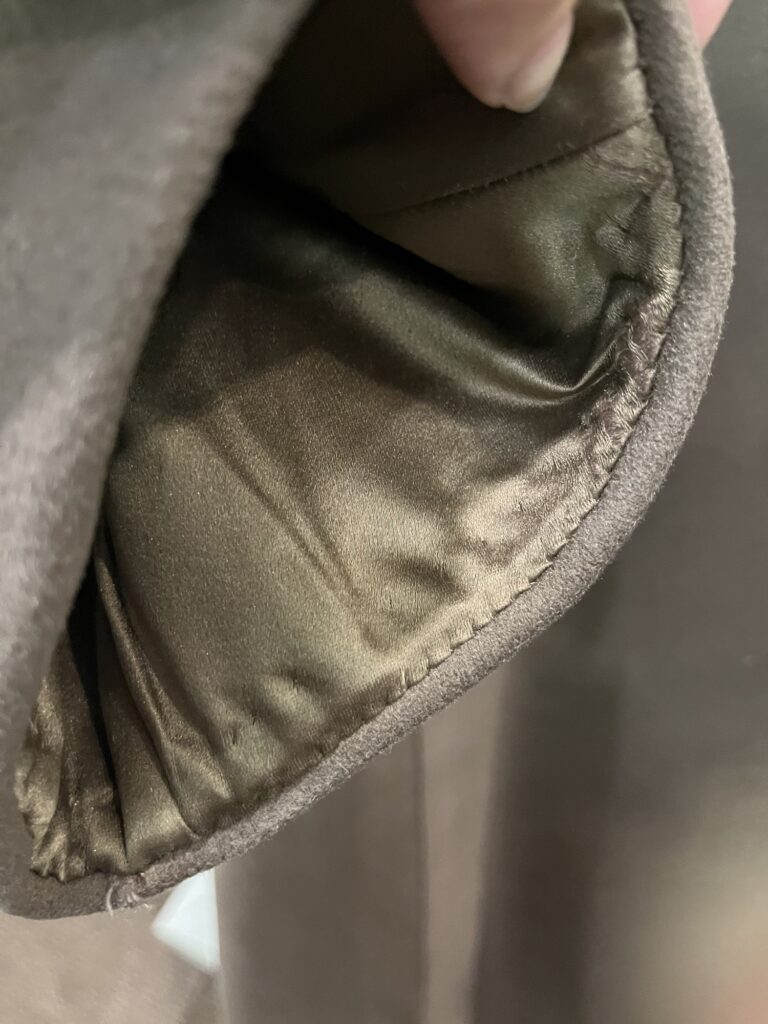

Clothing made for department stores, such as this wool broadcloth coat (c. 1900), are impressive examples of goods made when mass-production was possible, but consumer expectations remained high. The coat has parallel lines meticulously stitched on its yoke and down its front and back, elongating its wearer’s silhouette. The faux double-breasted front is cut straight, and the back lightly fitted to accentuate the fashionable shape at the time and conveniently permitting it to fit wearers in a range of sizes. Large, round mother-of-pearl buttons and dusky brown velvet cross-stitched over the collar provide additional contrast and textural interest. The coat’s slim sleeves and simple, sleek cut stand in contrast to those from about a decade prior, which featured large, puffed sleeves and curve-hugging princess seams.

Left: Fashion illustration titled “Street Costume” by A. Izambard (St. Petersburg) in Coming Styles Designed by the Great Costumers of Europe, fall and winter 1896, published for Marshall Field & Co. by Rand, McNally & Co. CHM, ICHi-037454_h. Right: Sketch of coat on a wearer by Grace Koehler, 2024.

Closer inspection shows the thought put into the needs of the wearer, with a pocket neatly hidden in the self-fabric trim extending from the yoke as well as two breast pockets built into the front facing in a satin matching the fully lined interior. There is also a slit hidden in the back of the coat, also disguised by trim, perhaps to access a back skirt pocket?

The sleeves and hem appeared to be felled down with nearly invisible hand stitches.

On the inside of the coat at the nape is a label that appears to have been resewn by someone with less deft hands than the coat’s maker, turned upside down and backwards. It reads: “MAYER Chicago.” This coat was most likely purchased from the department store Schlesinger & Mayer.

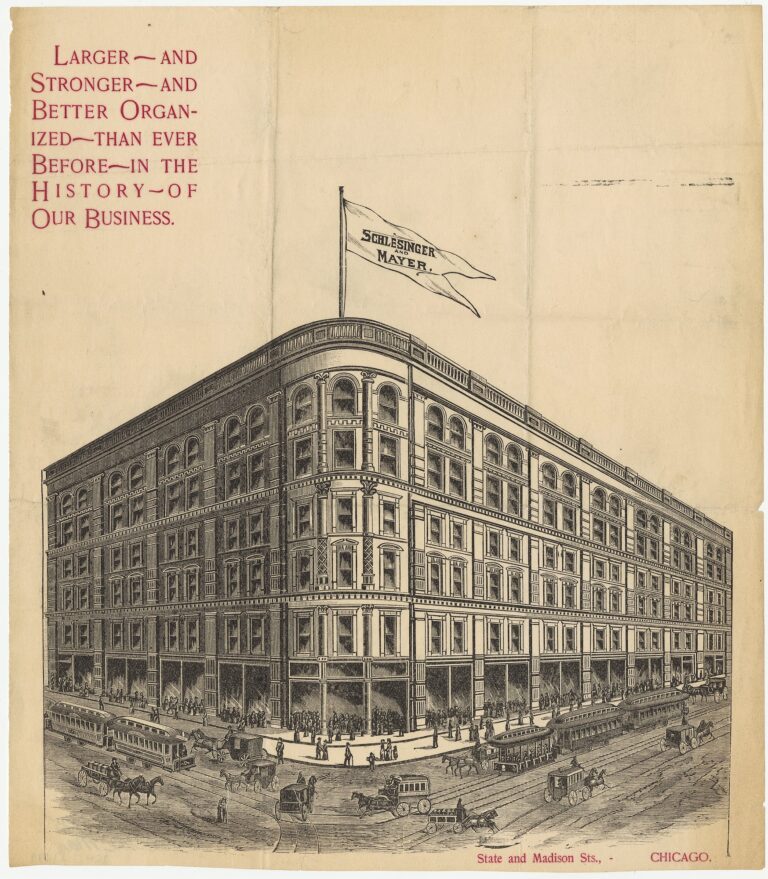

Advertisement for Schlesinger & Mayer, Chicago, 1873. CHM, ICHi-061679

Though the company had existed in Chicago since 1872, they commissioned architect Louis Sullivan to redesign their department store, which employed close to 2,500 people, at the corner of State and Madison Streets in 1899. After its completion in 1904, Schlesinger & Mayer could no longer afford to operate it, so they sold it to Carson Pirie Scott.

The coat’s owner was most likely a woman named Carrie Spooner Case, mother of its donor, Carolyn Case Norem. Carrie, with her husband Francis M. Case, was a Cook County resident around the time the coat was purchased. By the looks of her family photographs, she was an upper-middle or upper-class woman, making her an ideal customer at a department store. She may have visited the Schlesinger & Mayer storefront or flipped through their mail-order catalog until she found a coat that piqued her interest. Regardless, she certainly picked a practical, well-made coat that would last for years to come.

Claude M. Lightfoot (1910–1991) was an African American author, Chicago resident, political candidate, and member of the Communist Party USA’s national committee. In 1986, he donated a collection of his papers to the Chicago History Museum.

Portrait of Claude M. Lightfoot from Harold Marcuse, The Case of Claude Lightfoot, 1955 brochure. Public domain.

Born in Lake Village, Arkansas, in 1910, Claude Mark Lightfoot was raised by his grandmother until 1918 when the Lightfoot family moved to Chicago as part of the Great Migration. The Chicago Race Riots of 1919 stirred Lightfoot’s interest in politics and racial equality that would drive his life’s work.

In the wake of World War I, he joined Marcus Garvey’s Pan-Africanist movement, but he soon became convinced the ideology was unworkable. After a brief time at Virginia Union University—where he was expelled after the school discovered he did not have a high school diploma—he returned to Chicago in 1929.

Lightfoot joined the Democratic Party and helped found the Young Men’s Black Democratic Club in Chicago (1930). At this point in his political development, he was convinced that the answer to the plight of African Americans would be found in business enterprise. However, the Great Depression and the lack of progress and action regarding Black Americans’ financial and political standing convinced him otherwise.

In 1931, Lightfoot joined the Communist Party USA (CPUSA). In summer 1932, he attended a workers’ school organized by the Party, and later that year he ran for Illinois State Legislature on the Communist Party ticket and received 33,000 votes. By 1935, Lightfoot was a delegate to the Seventh World Congress of the Communist International in the Soviet Union.

After the Nazis declared war on the Soviets during World War II, Lightfoot enlisted in the US Army in 1941. The prejudiced treatment of both Communists and Black soldiers by the Army deepened Lightfoot’s belief in socialist government. He resumed his CPUSA activities upon his return home three years later. In 1946, Lightfoot prepared to run for the Illinois State Senate on the CPUSA ticket; however, his petition was successfully challenged by the Democratic Party—the Cold War had begun.

Undated photograph of Claude Lightfoot (right) with Jack Kling at an unknown location. CHM, ICHi-039210

On June 26, 1954, Lightfoot, then serving as the executive secretary of the Communist Party of Illinois, was arrested and charged with Communist Party membership and knowledge of the Party’s objectives “to teach and advocate the overthrow of the government of the United States by force and violence as speedily as circumstances would permit” as specified in the Smith Act of 1940. It was the first indictment under this clause, so Lightfoot’s case was a test case for both the defense and prosecution. Lightfoot believed the federal government targeted him to send a message to Black Americans to stay away from the Communists (and civil rights activities in general).

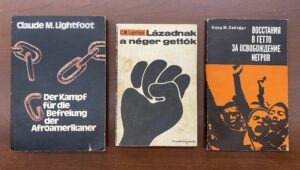

German, Hungarian, and Russian translations of Lightfoot’s Ghetto Rebellion to Black Liberation. Claude M. Lightfoot papers, Series 2, Box 2.

Lightfoot’s case was appealed all the way to the US Supreme Court, where Lightfoot was acquitted in 1964. That year, the Supreme Court also struck down the provision of the McCarran Act that withheld passports to CPUSA members. From 1964 until his death in 1991, Lightfoot worked for the CPUSA as a party officer and sought the advancement of Marxist-Leninist ideals. He wrote numerous books and articles about racism and communism and gave lectures around the world. In 1973, he received an honorary doctorate from the University of Rostock in Germany for his book, Racism and Human Survival: Lessons of Nazi Germany for Today’s World.

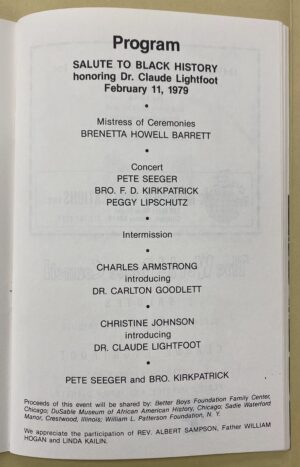

“Salute to Black history honoring Dr. Claude [M.] Lightfoot,” Feb. 11, 1979 program. Claude M. Lightfoot papers, Series 1, Box 1, Folder 23.

Today, the Claude M. Lightfoot papers [manuscript], 1950–85, n.d. (bulk 1969–85) can be accessed through the Abakanowicz Research Center, which is free to visit. The materials include correspondence, speech and manuscript notes, publicity information, reviews of his books, clippings and copies of Lightfoot’s newspaper columns in the Chicago Courier, and sound recordings of speeches by and about Lightfoot.

Lightfoot’s life, personal and professional, is chronicled in his autobiography, Chicago Slums to World Politics: Autobiography of Claude M. Lightfoot.

To mark the centennial of Maria Tallchief’s birth, CHM costume collection manager Jessica Pushor shares a bit about the prima ballerina’s life and a sampling of garments she donated to the CHM costume collection.

Maria Tallchief, Chicago, February 27, 1966. ADN-0000060, Chicago Daily News/Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM; Edward DeLuga for Chicago Sun-Times, photographer

Maria Tallchief, famed ballerina, was born Elizabeth Marie Tall Chief on January 24, 1925, in Fairfax, Oklahoma, to Alexander Joseph and Ruth Tall Chief. Her father was a member of the Osage Nation, and her mother was Scotch-Irish. Tallchief was widely considered the first major prima ballerina to hail from the US and was the first Native American to hold that distinction. She danced with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo from 1942 to 1947 but is best known for her time with the New York City Ballet from 1947 to 1965 and served as prima ballerina.

Studio/publicity photograph of Maria Tallchief, 1947. Image 3, Larry Colwell Dance Photographs, Library of Congress.

During her dance career, Tallchief was married to choreographer George Balanchine from 1946 to 1952, then private pilot Elmourza Natirboff from 1952 to 1954. In 1955, while on tour in Chicago, she met Henry D. “Buzz” Paschen Jr., a construction company executive. In her Chicago Tribune obituary, she is quoted as saying that Buzz “was very happy, outgoing, and knew nothing about ballet—very refreshing.” They married the next year and in 1959 welcomed a daughter, Elise, Tallchief’s only child.

Undated photograph of Maria Tallchief, teaching, with a dancer at the Lyric Opera of Chicago. CHM, ICHi-036422

After Tallchief retired from dancing in 1965, she was appointed ballet director at the Lyric Opera of Chicago in 1971, a position she held for two decades, and was the founder and co-artistic director of the Chicago City Ballet (1981–87).

Maria Tallchief (center) speaks with two dancers at a Chicago City Ballet performance at St. James Cathedral Plaza, 65 E. Huron St., Chicago, June 10, 1981. ST-12002371-0037, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Maria Tallchief had a long affiliation with the Museum, as she donated a total of 17 ensembles to the costume collection beginning in 1974 until 1992.

Dress, 1947. Wool crepe and silk velvet. Christian Dior, France. Gift of Mrs. Henry D. Paschen. CC.1974.483

This dress by Christian Dior is the Museum’s only garment from the Corolle line, Dior’s historic first haute couture Spring-Summer 1947 collection, the opening of which Tallchief attended. Tallchief purchased this dress—titled “Maxim,” after Dior’s favorite restaurant—and wore it when she received the 1953 Woman of the Year award from President Dwight D. Eisenhower. This dress was also the first donation Maria Tallchief made to the Chicago History Museum’s costume collection, and one of two Diors she donated.

Cocktail dress, c. 1954. Silk faille. Christian Dior, France. Gift of Mrs. Henry D. Paschen. 1980.142a-b

The other Dior is this cocktail dress, which still has its import tax seal attached to the interior side seam, and is the only Dior dress in the Museum’s collection that still has that seal.

Evening ensemble, c. 1984. Silk crepe and satin, sequin, glass beads. James Galanos, United States. Gift of Mrs. Henry D. Paschen, 1990.665.1a-c. Left: ICHi-063887, right: ICHi-063889

In 1990, Tallchief made her largest donation to CHM’s costume collection—12 garments by a variety of fashion designers including Mary McFadden, Geoffrey Beene, Zandra Rhodes, Bill Blass, and this ensemble by American fashion designer and couturier James Galanos. Designed in 1984, this three-piece evening ensemble of black silk chiffon and silk satin features shoulders and arms trimmed with red sequins and bugle beads, a full-length wrap skirt, and a separate cummerbund that wraps around the waist and hips. Tallchief purchased it at Bergdorf Goodman in New York.

For her contributions to American ballet, Tallchief was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 1996, and in 1999 she received the National Medal for the Arts and the Theodore Thomas History Maker Award for Distinction in Performing Arts at the Chicago History Museum’s yearly Making History Awards. Maria Tallchief died on April 11, 2013, the age of 88. She was posthumously inducted into the National Native American Hall of Fame in 2018.

Additional Resources

- Read “Creating a Dance: Interviews with Bruce Graham and Maria Tallchief,” Chicago History (Spring 2000)

- View more items in the CHM Costume and Textiles Collection