Latest Posts

CHM collections intern Ella Trotter writes about the critical process of describing archival documents regarding enslaved people in the United States.

The Chicago History Museum’s Abakanowicz Research Center holds a collection of more than fifty documents, manuscripts, and letters regarding enslaved people in North America. The largely handwritten collection offers a glimpse into the lives of enslaved people through the writing of enslavers, buyers, and auctioneers. For my internship at CHM, I was asked to engage in an archival description process and provide unique titles for all the objects in this collection as part of CHM’s larger critical cataloging work. During this process, a certain set of objects caught my special interest: the manumission (release from enslavement) documents from Robert Carter, who was born into one of the wealthiest families in Virginia and heir to hundreds of enslaved people. For three decades beginning in 1791, Carter systematically freed more than 500 people he enslaved, making him the protagonist of one of the largest individual acts of manumission in the United States before 1860.

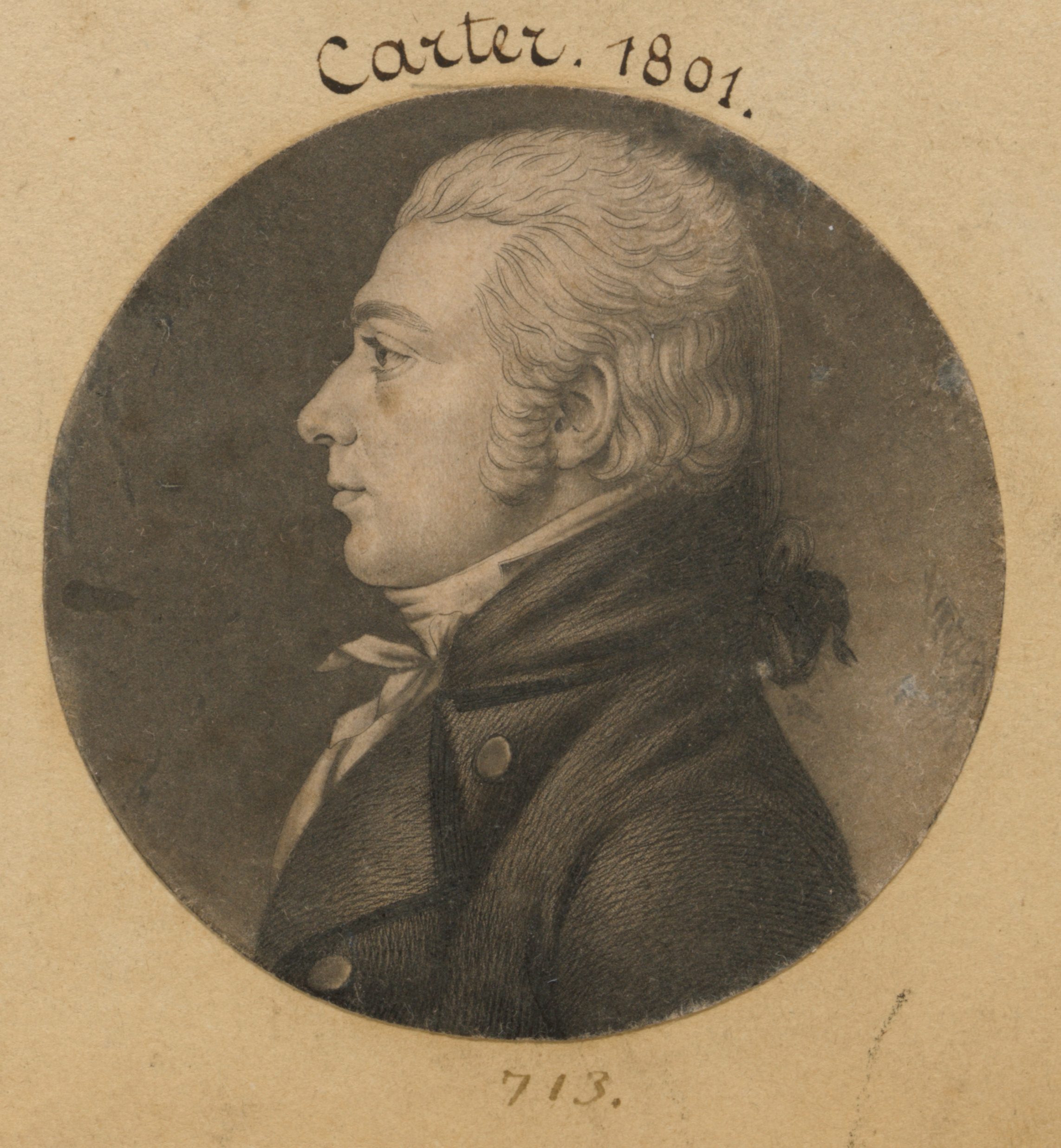

Engraving of Robert Carter, 1801. Charles Balthazar Julien Févret de Saint-Mémin, artist. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Although Carter could be considered politically and morally progressive for willfully freeing the people he enslaved, his story is not representative of the rest of the white landowning community of the time. Archival description strives for neutrality and passivity of facts; however, it is also a form of classification and storytelling. Throughout this project, I was at times overwhelmed by the agency I had to describe these valuable historical documents, and I learned firsthand that archival description is not neutral or passive at all. I did not want to replicate injustice within my archival descriptions, and I wanted the story I tell to center enslaved people and their experience first and foremost.

According to the Describing Archives Content Standards (DACS), object titles should include the name of the person who is “predominantly responsible for the creation, assembly, accumulation, and/or maintenance of the materials.” When thinking about documents from the pre-Civil War United States, it is very rare for any documents to be created by enslaved people on account of their lack of access to reading and writing. Based on the DACS standards, the titles of almost all documents that hold within them precious information about enslaved people and their stories will have the names of white enslavers and auctioneers.

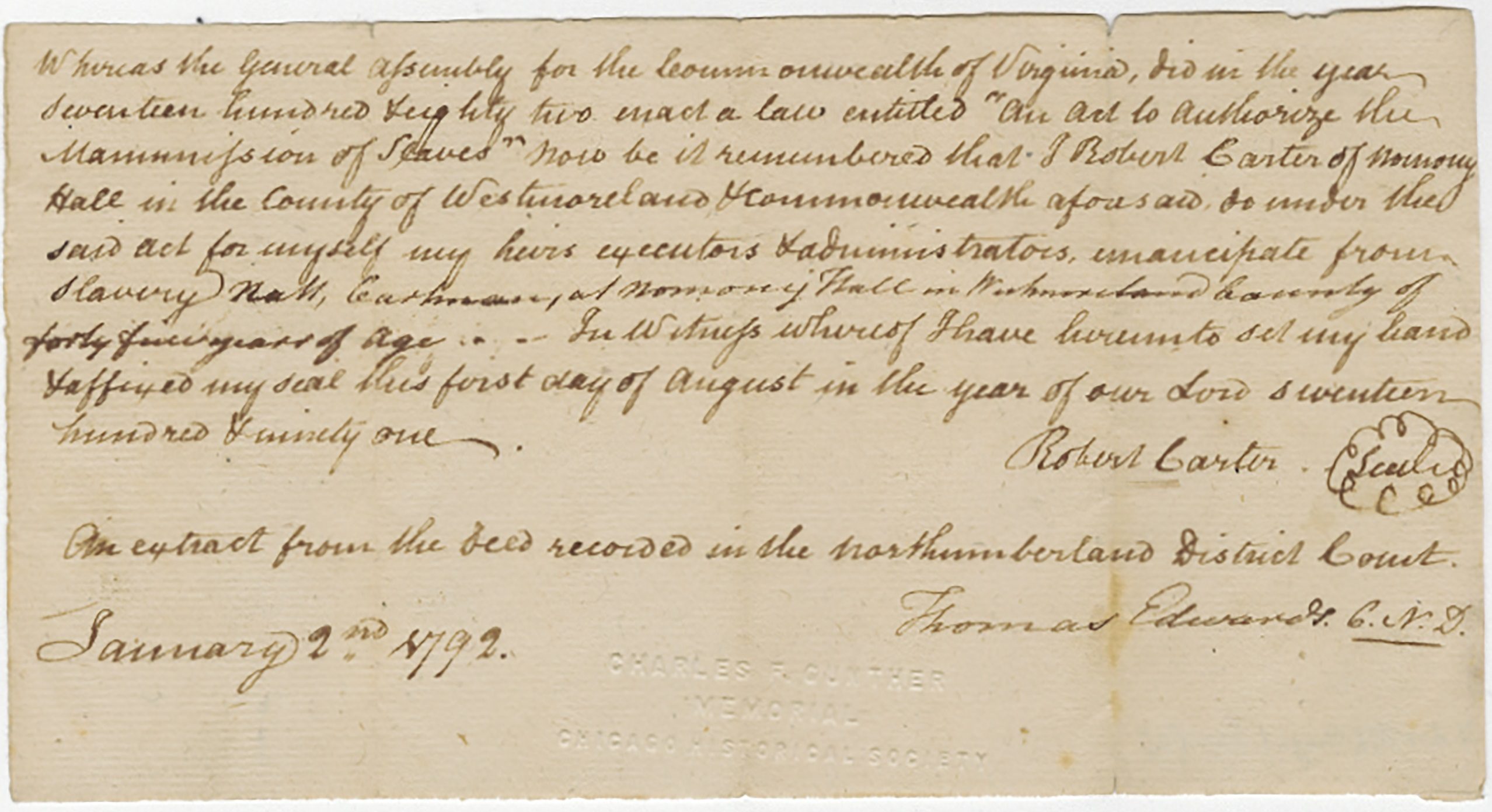

After researching and learning more about DACS, the question became whose name should be in the title, and what would it mean? Considering Carter’s historical recognition, including only his name in the title of the documents would be sufficient from a research standpoint. However, for this collection I decided to title the manumission documents with the newly freed person’s name, such as “manumission of Natt.” The full title would be “Robert Carter manumission of [Name], [Date].” With this title format, we are able to keep both the name of Robert Carter to satisfy the standards and the newly freed person’s name, which is not solicited by the standards.

Letter written by Robert Carter, January 2, 1792. CHM, ICHi-176982

Robert Carter presents an interesting example of how changing the title of an object can change the story. In the past, many records of enslaved people’s names and memories have been erased due to a mix of not having records or names and a difference in what is deemed a standard archival practice. However, in these manumission documents the names are available to us. Centering their names in order to not continue the erasure and dehumanization of African American enslaved people might create a small sense of justice. In order to continue rectifying archival description, we must continue to vigorously and critically discuss what story we wish to tell.

The Chicago History Museum’s Abakanowicz Research Center (ARC) is proud to announce the unveiling of a new catalog interface—Enterprise from SirsiDynix. CHM librarian Gretchen Neidhardt talks about this new interface, which allows us to offer you more resources in one place and provides more accessibility and flexibility in searching.

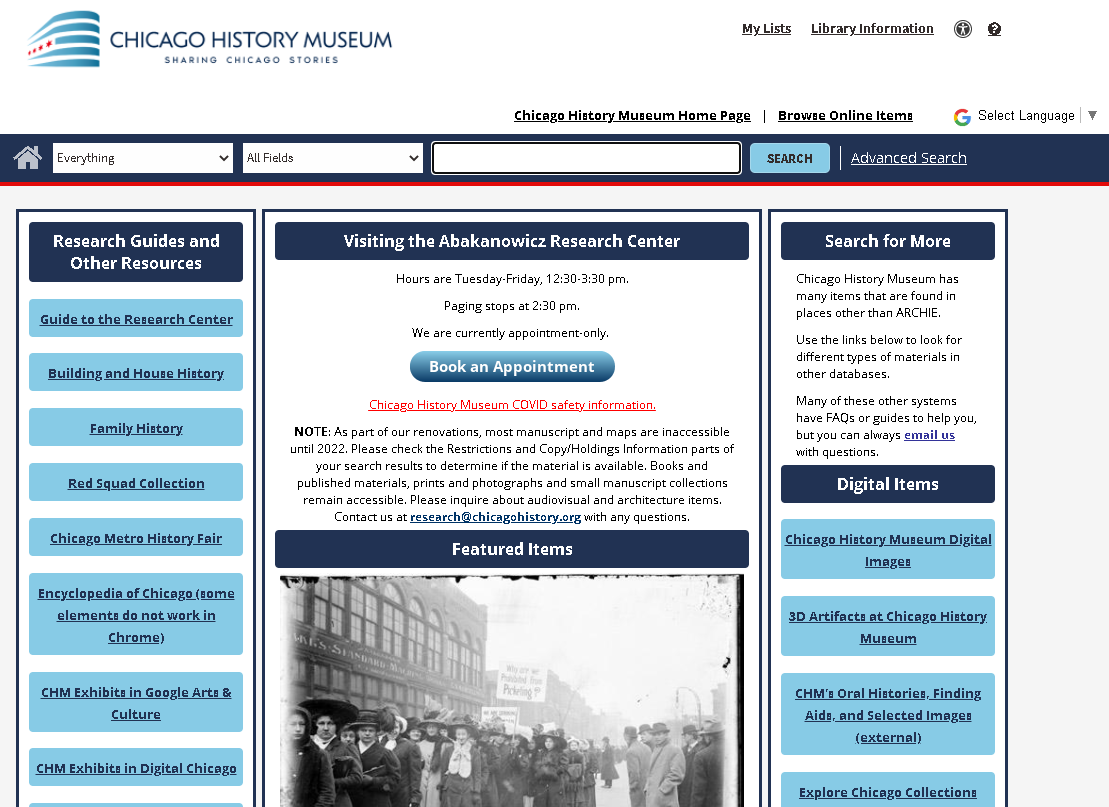

After several months of work, ARC staff is excited to unveil its new library catalog interface, otherwise known as ARCHIE. While it looks different from the previous version, the search functions are still largely the same, and the items you are searching for are still the Museum’s research collections (published items, prints and photographs, archives and manuscripts, and architecture materials).

There are a few changes to how you can search. First, you’ll notice that we have put all of our resources on the front page. The instructional video above will take you through the specifics, but we are very pleased to have a central location that leads you to our resources like research guides, digital exhibits, images, and digitized item databases.

The new ARCHIE landing page

Searching works a little differently now, too. You no longer have to search for an exact spelling–ARCHIE will return results that are spelled similarly and will automatically sort these items by relevance, rather than by the order in which they were added to the catalog. There are also now facets on the left of your search results where you can include or exclude certain search parameters immediately.

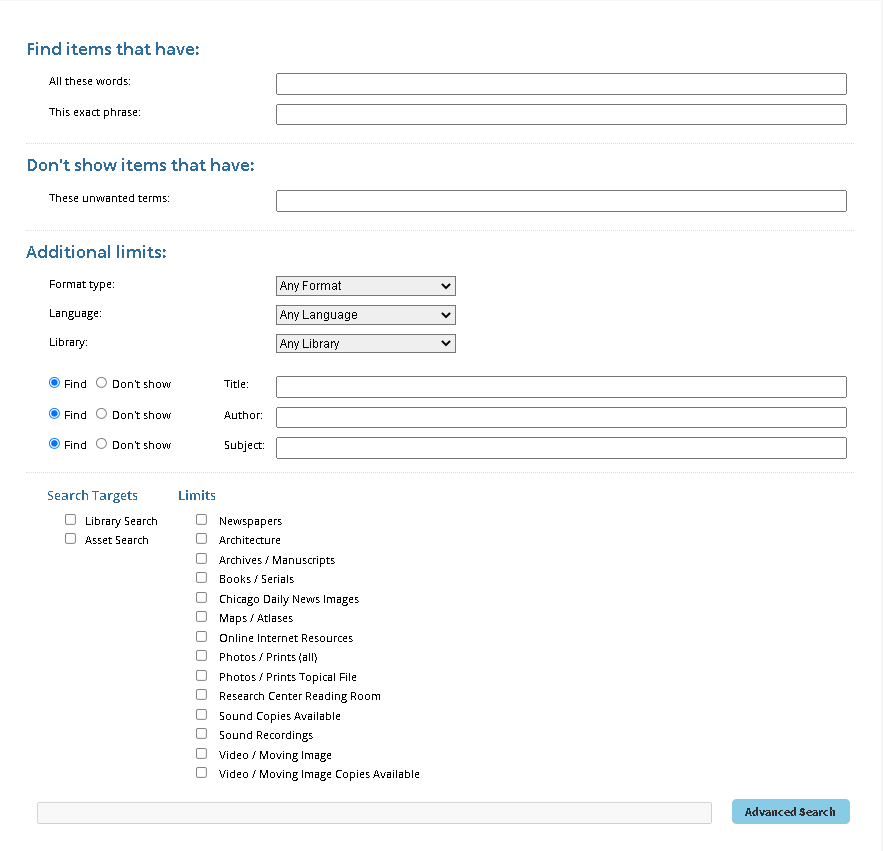

Advanced Search function

However, search parameters remain largely the same. On the first page you can still limit your search by both material format (books, photographs, mixed materials [e.g., archival collections], etc.) or limit which field (title, author, etc.) you are searching within. You can also use these search operators:

- quotation marks to search for an exact phrase like “studs terkel”

- a hyphen with no space to indicate “not” like “studs -terkel” will return all results with “studs” but not “terkel”

The above are shortcuts for the Basic Search. Almost all of them are spelled out in the Advanced Search. Advanced Search is also the only place right now you can look for “assets.” These are files that you can search separately from catalog records about an item.

A quick note about search functionality that doesn’t exist in this new interface—except for the searching described above, Boolean operators will not work.

You can still add items to your list, and you can email, text, or print those lists. Please note, though, that they are temporary and will only be saved for as long as your browser window is open. You can learn more by clicking on the “help” icon on the top right of any ARCHIE screen.

Search results page

We also have increased our accessibility options. You’ll see a Google link to change the language of the text appearing on the page. You can always revert this by changing back to “English” or pressing the back button. If you require a higher contrast and/or larger text interface, please press the accessibility icon on the top right, to the left of the help icon.

Lastly, we have always welcomed your feedback about our website and our item descriptions. Now we hope this will be easier than ever. At the bottom of every page in the dark blue footer there is a link to “Help improve this content.” You can fill out that short form with any information you think we should know. We welcome your feedback as we continue to improve our user experience.

If you have an urgent question or cannot attend one of our drop-in sessions, please email research@chicagohistory.org.

The Chicago History Museum today announced that The Abakanowicz Arts and Culture Charitable Foundation has approved an award of $1,000,000 to complete the renovation of the Museum’s research collection facility. The gift will ensure that the Museum’s library and archive holdings are properly preserved and provide access to scholars and the public. A dedication ceremony will take place at the Museum on July 26th, at which point the Research Center will officially be named The Abakanowicz Research Center.

“The Chicago History Museum is dedicated to making our research collections accessible to everyone and this generous gift from The Abakanowicz Arts and Culture Charitable Foundation will allow us to expand our collections and preserve materials for generations to come,” said Donald Lassere, president and CEO of the Chicago History Museum. “It is through our research collections and continued work across communities that we are able to share Chicago stories from diverse perspectives, and we are grateful to The Abakanowicz Arts and Culture Charitable Foundation for this gift to further our mission.”

In addition to preservation and access of the Museum’s renowned research collection, this generous gift will support several elements of the research center facility and collections, including compaction storage, the installation of a new waterproof roof, updated lighting, HVAC systems and other necessary elements for collecting and preservation. It will also provide support for programs and activity such as the Chicago Metro History Fair, house histories, new scholarship, and further research into Chicago communities.

The Abakanowicz Arts and Culture Charitable Foundation honors the legacy of Magdalena Abakanowicz (1930-2017), a renowned artist of the twentieth century and pioneer of fiber-based sculpture and installation. Influenced by her life in Poland under Nazi and Soviet occupation during World War II, her work draws from various experiences, encouraging multiple interpretations, and highlights her belief in history determining the future of society and cultures. She is best known in Chicago for her public work, Agora (2006), in Grant Park. The designation of the Abakanowicz Research Center underscores the artist’s commitment to truth in history, the value of telling diverse stories, and her long association with the city of Chicago.

For more information on the Abakanowicz Research Center and availability of research collections, please visit: www.chicagohistory.org/research

The Chicago History Museum will commemorate the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 in its newest family friendly exhibition. The devastating grief and subsequent growth sparked by the destruction of the fire is remembered in City on Fire: Chicago 1871, opening to the public on Friday, October 8, 2021.

“The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 was a pivotal event in the city’s history, setting it on a path of unmatched resilience and constant evolution that still defines Chicago today,” said Julius L. Jones, lead curator for the exhibition. “We are honored to tell this important Chicago story in a way that helps our visitors draw parallels to the present-day.”

Beginning on October 8, 1871, the Great Chicago Fire burned through the city for three days. After the flames subsided, recovery efforts exposed deep social and economic inequities as more than 100,000 people became homeless, and society placed blame upon the Irish immigrant O’Leary family. 150 years later, City on Fire: Chicago 1871 highlights the crucial events and conditions before, during, and after the fire.

Designed for families, City on Fire: Chicago 1871 explores the impact the fire had on the city and its people. The exhibition will take visitors through events and conditions that led to devastation and recovery and shed light on what life was like in 1871. Following the detailed path of the fire, from the O’Leary’s barn north and east through the city, visitors will be immersed in the destruction of the fire and the decisions that civilians were faced with as they fled danger. Visitors will learn about recovery efforts that called for reformed fire safety procedures that are still in use today, underscoring the deep and lasting impact the fire had on Chicago’s past and present.

“The Chicago History Museum is committed to sharing Chicago stories and connecting our diverse communities through shared experiences,” said Donald Lassere, president and CEO of the Chicago History Museum. “While the devastation of the Great Chicago Fire was felt by all in the city, the rebuilding efforts exposed inequities. We are honored to facilitate this important discussion and welcome visitors to City on Fire: Chicago 1871 to learn more about this monumental event in our city’s history.”

City on Fire: Chicago 1871 features more than 100 pieces from the museum’s collection, interactive multimedia elements, and personal stories from the O’Leary and Hudlin families, and other survivors of the fire. A large-scale reproduction of a cyclorama painting depicting the breadth of the fire’s path across the city is the pinnacle of the exhibition, on display for the first time in generations. The original was a main attraction during the 1893 World’s Fair, standing nearly 50 feet high and 400 feet long, it occupied its own building on Michigan Avenue for spectators to gather and observe. Historic heirlooms and cherished personal belongings damaged in the fire will also be on display.

For more information on City on Fire: Chicago 1871 please visit: www.chicago1871.org

The Chicago History Museum and OUT at CHM, in partnership with Association of Latinos/as/x Motivating Action (ALMA), is honored to present the premiere screening of “Seguimos Aqui (We’re Still Here): Pride, Pandemic & Perseverance.” The 30-minute documentary will premiere at the Museum on July 22nd at 7:00 p.m. followed by a panel discussion and reception. The screening is free to the public and will also be streamed on the museum’s Facebook page and YouTube channel.

“The Chicago History Museum and OUT at CHM are proud to partner with ALMA to tell the dynamic stories of Latinx LGBTQIA+ communities in Chicago and hear first-hand of their experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic,” said Donald Lassere, president and CEO of the Chicago History Museum. “It is imperative to elevate their voices and tell Chicago stories from dynamic perspectives and we are honored to bring ‘Seguimos Aqui (We’re Still Here): Pride, Pandemic & Perseverance’ to our audiences.”

Produced by SoapBox Productions and Organizing, “Seguimos Aqui (We’re Still Here): Pride, Pandemic & Perseverance” tells the stories of four LGBTQ+ identifying Latinx Chicagoans as they navigate the COVID-19 pandemic, interpersonal struggles, and community triumphs throughout a turbulent yet powerful 2020. Alma A. Vásquez “Nissa Conde”, entertainer and artist, Luis Lira, community health advocate for Esperanza Health Centers, LaSaia Wade, Founder and Executive Director of Brave Space Alliance, and Reyna Ortiz, Trans Resource Navigator and author of T: Stands for Truth: In search of the Queen Vol. 1 are Latinx LGBTQ+ leaders from different backgrounds who use the power of self-determination, love, and community to not only survive but help their communities.

For more information on the premiere screening of “Seguimos Aqui (We’re Still Here): Pride, Pandemic & Perseverance,” please visit: chicagohistory.org/event/premiere-screening-seguimos-aqui/

In our latest blog post, CHM cataloging and metadata librarian Gretchen Neidhardt writes about our ongoing critical cataloging work.

This spring, the Chicago History Museum’s Research and Access department was fortunate to host Dominican University practicum student Rebekkah LaRue, MLIS, to assist us in examining our LGBTQIA+-related language in ARCHIE, our online catalog. This work is part of the Research Center’s larger critical cataloging work, where we reflect on our own language biases—individual, institutional, and industry-wide. A vital part of this endeavor is examining our current and legacy language, researching how communities define themselves, indicating clearly when historical language is used, and creating guides to help researchers find both current and historical information about a wide variety of communities.

A view of the start of the eighteenth annual Pride Parade in Boystown, June 1987. ICHi-089096; Lee A. Newell II, photographer

LaRue’s work consisted of three main parts:

1. A survey of LGBTQIA+-related items in our research collections and what cataloger-supplied language was used in descriptions and subjects.

2. An assessment of current subjects and possible substitutions, which up until now were pulled from the Library of Congress Subject Headings.

3. Creating a research guide explaining key community terms, which keywords to use to make the most of searching in ARCHIE, and terminology contextualization.

The survey returned approximately 230 items relating to some aspect of LGBTQIA+ history in Chicago, ranging from single books to entire photography collections. It is highly likely that more items exist in our collections but are not quickly accessible using modern terminology. As we discover these moving forward, we will adopt the same descriptive standards.

Activists gather in Daley Plaza, 50 W. Washington St., to protest police raids on LGBTQIA+ bars and businesses, Chicago, 1979. ST-17500885, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

After the initial survey, LaRue created a truly impressive assessment of the terminology used within and extracted all of the subject terms. These terms are part of what librarians call a “controlled vocabulary”–they remain the same across systems so that different-but-related items can be linked together. At CHM, we primarily use the subjects found in the massive list maintained by the Library of Congress, but these terms are often slow to change and are not always appropriate for our local communities. One example is the use of “gays” to serve as an umbrella term for various LGBTQIA+ communities. Another is “female impersonators,” which (for now) LOC recommends using instead of the more well-known (and generally preferred) term “drag queens.”

The Jewel Box Revue, a traveling drag review held at Robert’s Show Lounge, 6622 South Park Way (now King Drive), Chicago, 1956. CHM, ICHi-062195; James C. Darby, photographer

Luckily, others have also addressed this issue. We incorporated many new terms from Homosaurus, an international vocabulary of only LGBTQIA+ terms. We mapped and/or replaced existing Library of Congress terms to Homosaurus terms so that the usually more inclusive Homosaurus term would display publicly. Both the previous LOC term and the new term are still searchable, so a researcher using either would still find their desired items. When Homosaurus didn’t yet have an official term, LaRue constructed a local one for CHM, based on existing syntax, for instance, replacing “gay journalists” with “LGBTQ journalists.”

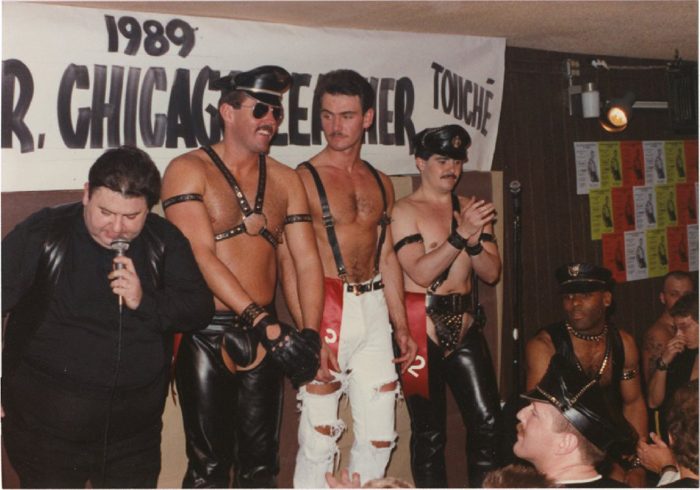

Contestants line up for the 1989 Mr. Chicago Leather competition at Touché, a leather bar in Rogers Park. ICHi-89092; Lee A. Newell II, photographer

Lastly, LaRue created a subject guide to explain our changes in terminology, suggest which terms researchers should use to find items in ARCHIE, give a contextual discussion of changing historic and present LGBTQIA+ identity terms, link to the CHM research collections heavily featuring LGBTQIA+ creators/topics, and lastly, list other local and national organizations that showcase LGBTQIA+ history. This is one of several new research guides that focuses on how to research communities and identities that are not always featured in special collections, and we welcome your feedback.

Additional Resources

- See more images depicting LGBTQIA+ history from our collection

- View our Google Arts & Culture exhibit Drag in the Windy City

- Read more blog posts about Chicago’s LGBTQIA+ history

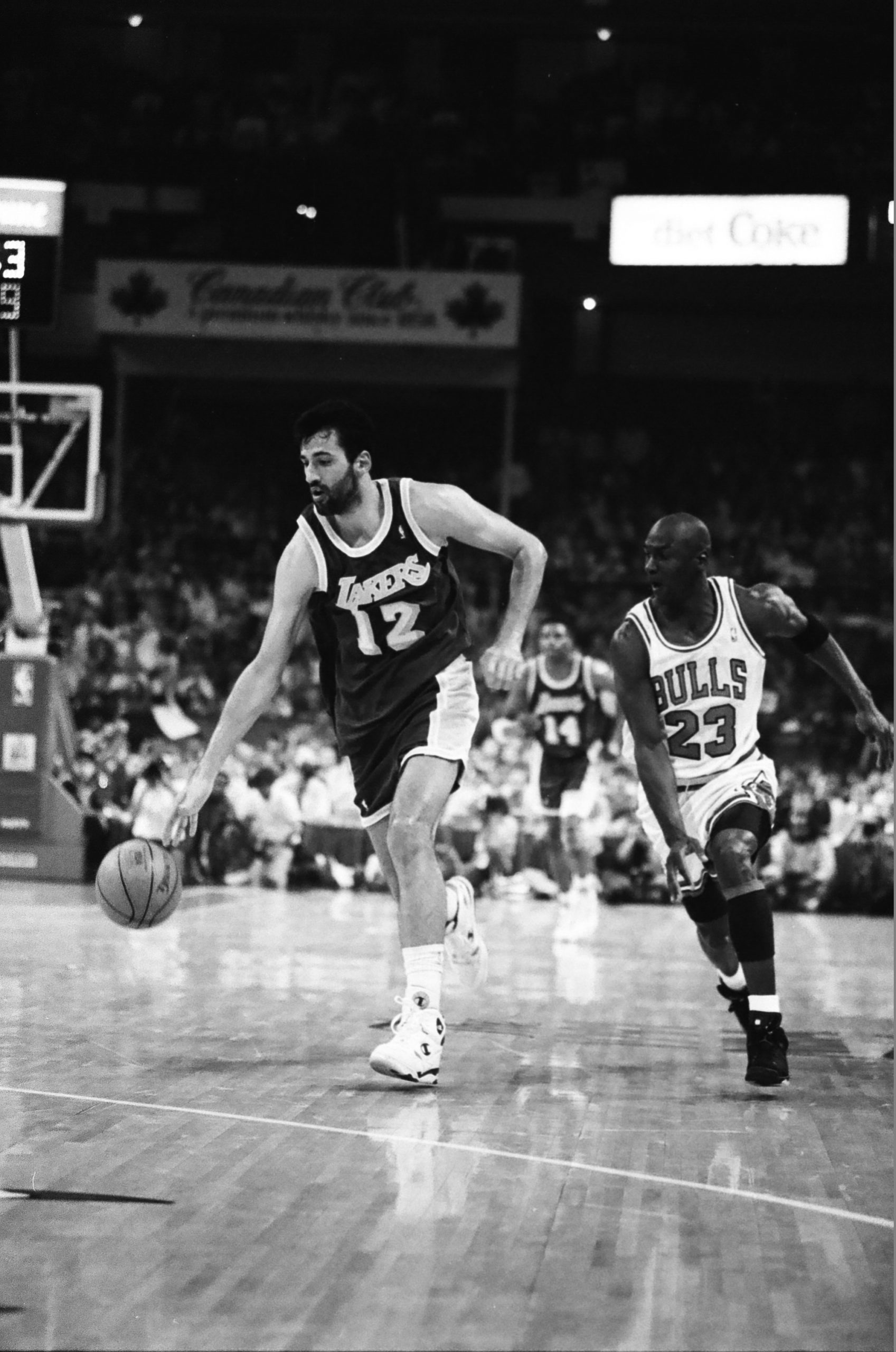

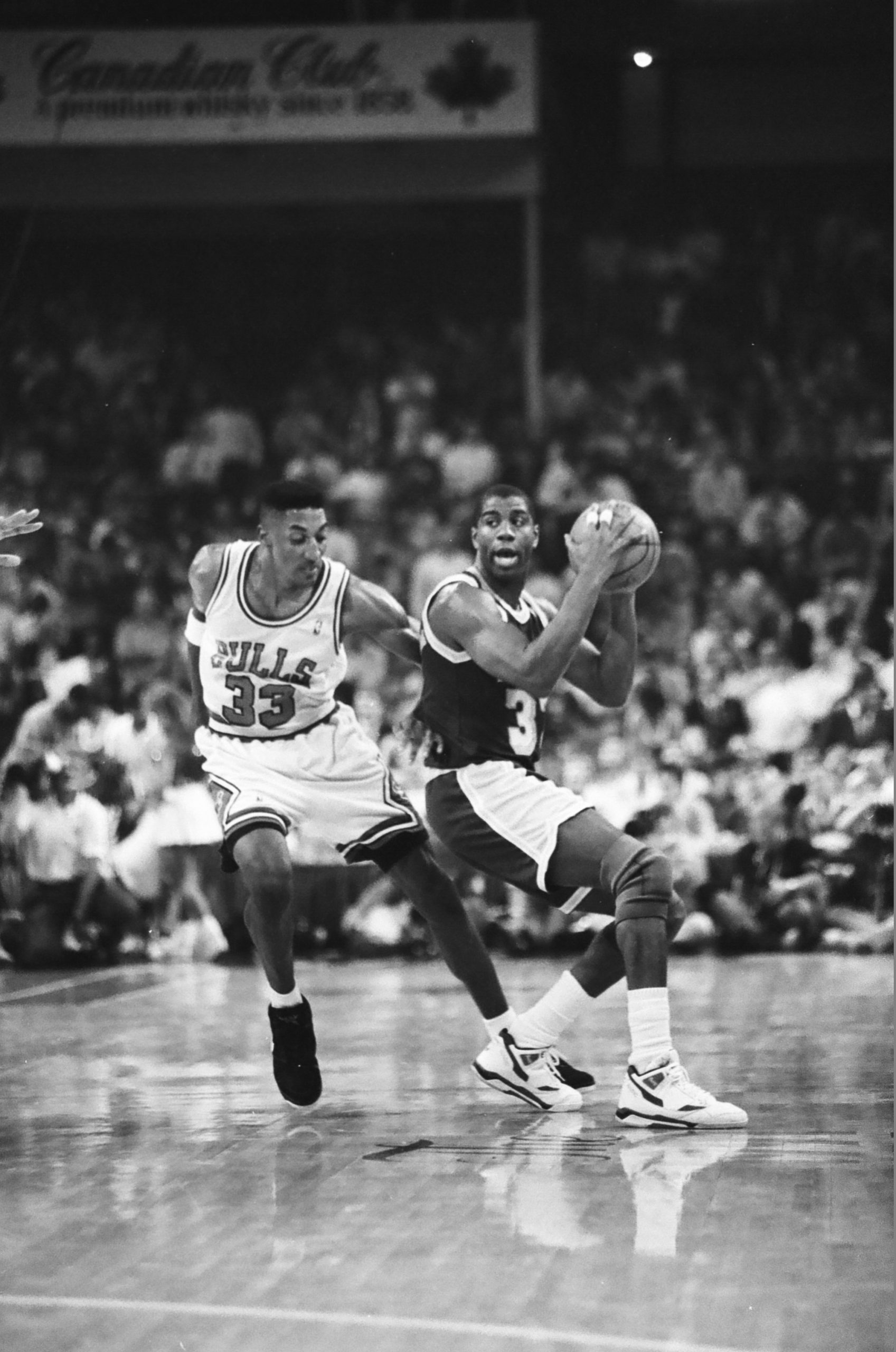

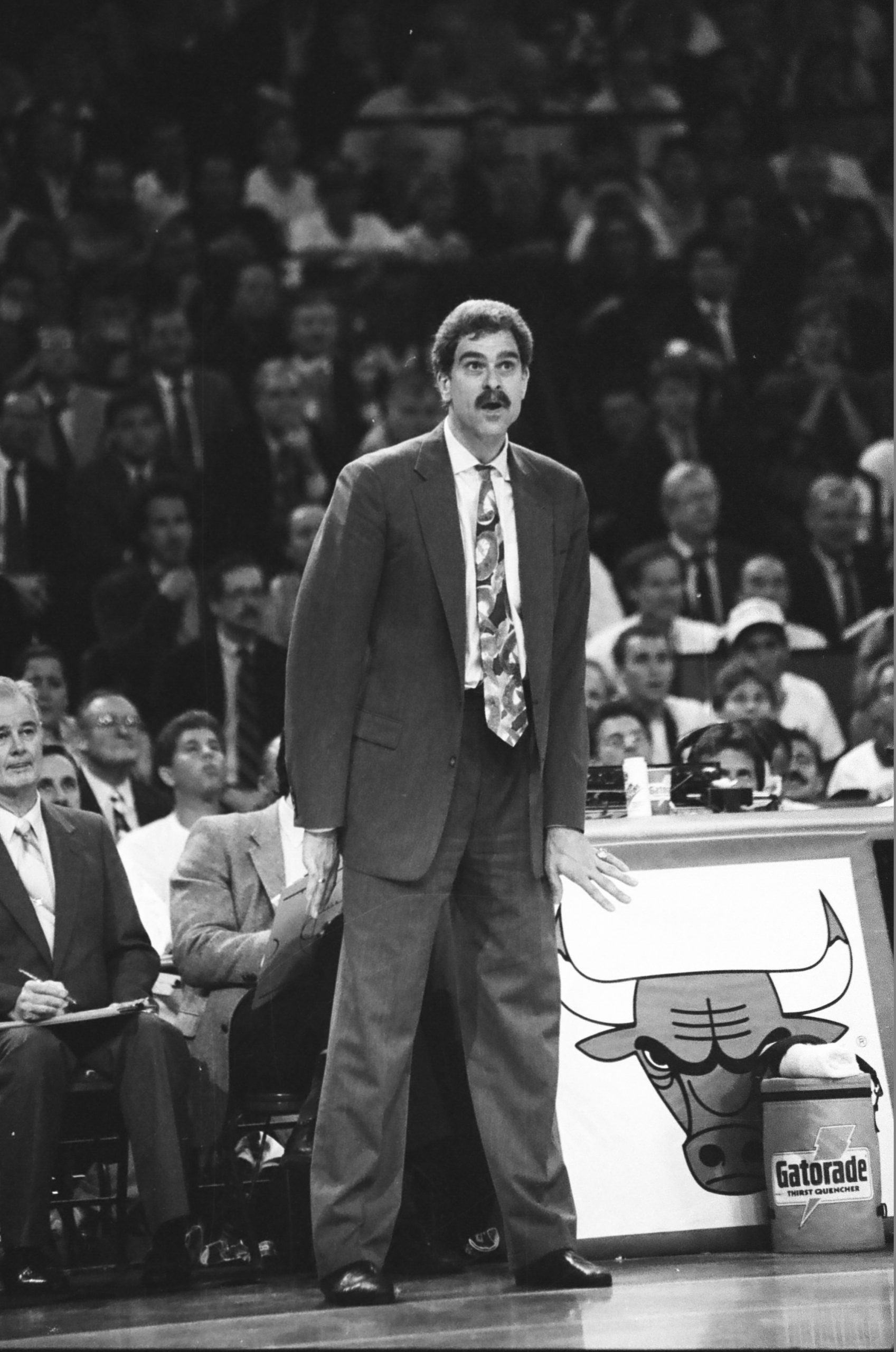

Thirty years ago today, the Chicago Bulls won their first NBA championship with a 108–101 victory over the Los Angeles Lakers. With a starting lineup of Michael Jordan, Scottie Pippen, Horace Grant, Bill Cartwright, and John Paxson, and led by head coach Phil Jackson, the Bulls won the final series in five games. This victory marked the start of the Bulls’ dominance in the 1990s, and they would go on to win five more championships in ’92, ’93, ’96, ’97, and ’98. The Chicago Sun-Times captured these images from Game 2 at Chicago Stadium on June 5, 1991.

Michael Jordan (Bulls #23) thinks about going for the steal against Lakers center Vlade Divac (#12), Chicago, June 5, 1991. ST-50004141-0006, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Scottie Pippen (Bulls #33) guards Magic Johnson (Lakers #32), in what would be the last championship series of Johnson’s Hall of Fame career. Though the series was billed as a matchup of Jordan vs. Johnson, Pippen defended Johnson throughout the Finals, Chicago, June 5, 1991, ST-50004141-0046, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

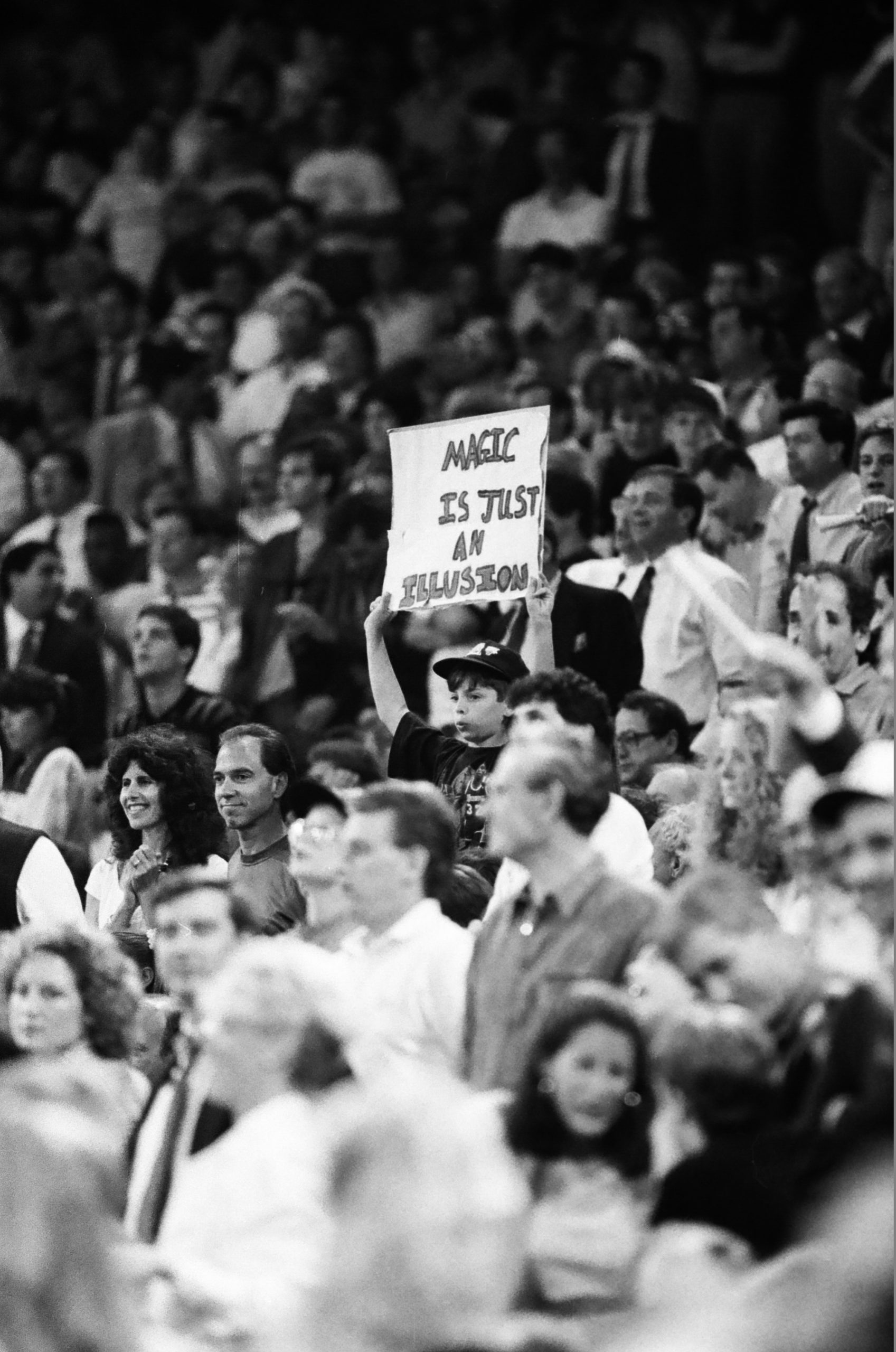

A young Bulls fan holds a sign that reads “Magic is just an illusion,” Chicago, June 5, 1991. ST-50004141-0017, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

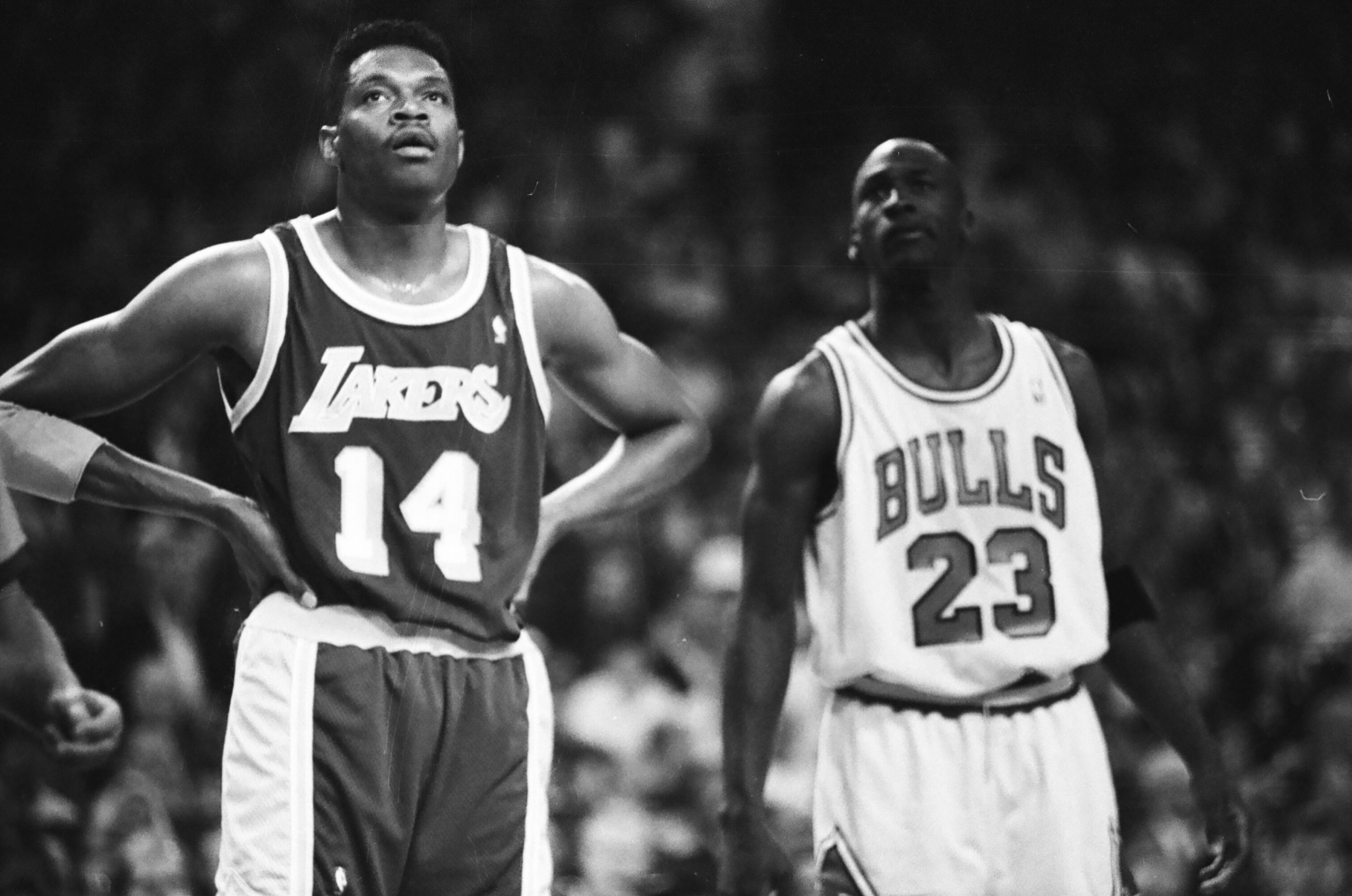

Sam Perkins (Lakers #14) and Michael Jordan (Bulls #23) were former teammates at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill from 1981 to 1984. ST-50004141-0008, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Bulls center Bill Cartwright (#24) looks for an open man while being guarded by Mychal Thompson (Lakers #43), Chicago, June 5, 1991. ST-50004141-0024, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

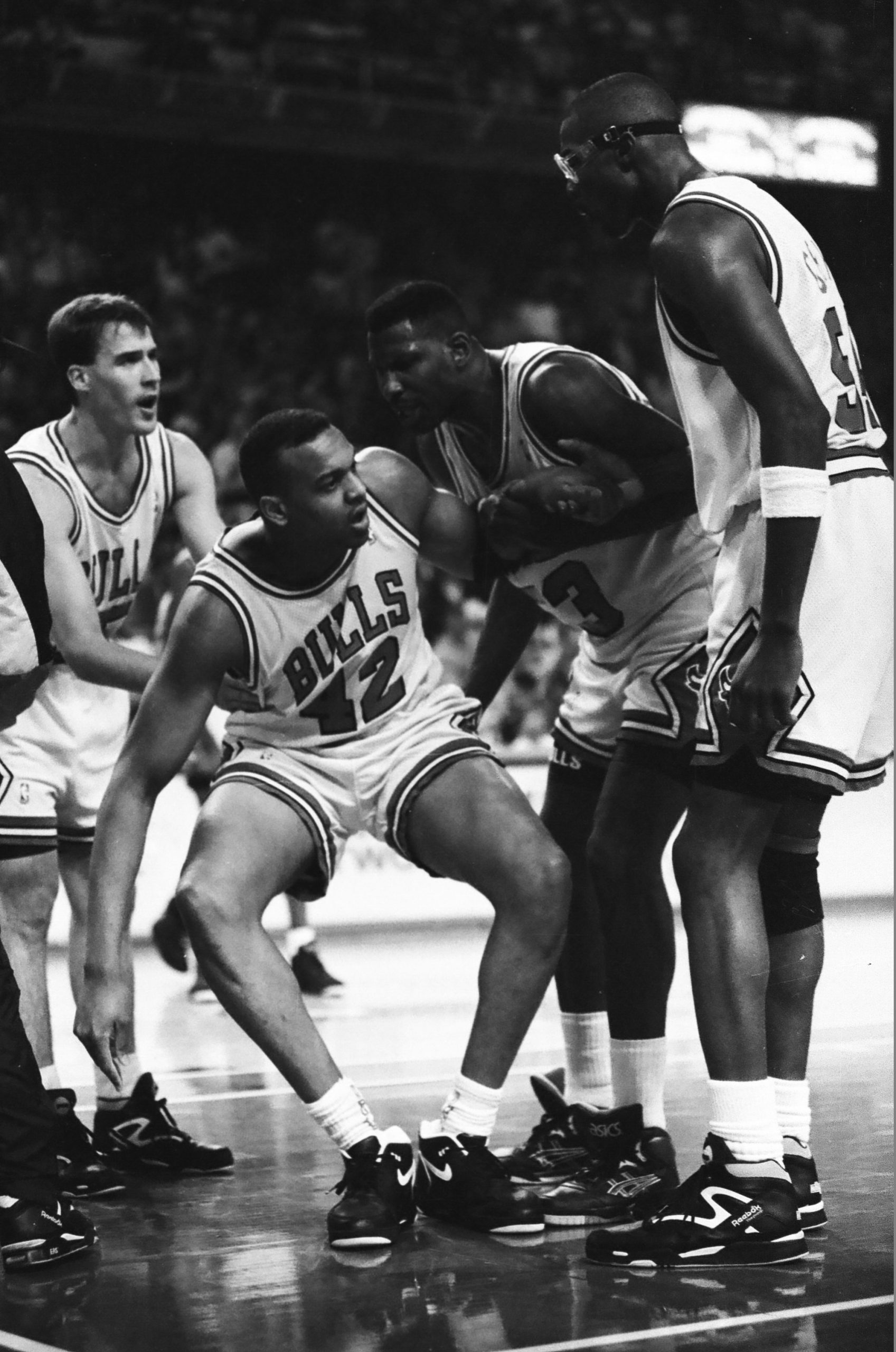

John Paxson (#5), Cliff Levingston (#53), and Horace Grant (#54) help up teammate Scott Williams (#42) after a hard fall, Chicago, June 5, 1991. ST-50004141-0003, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

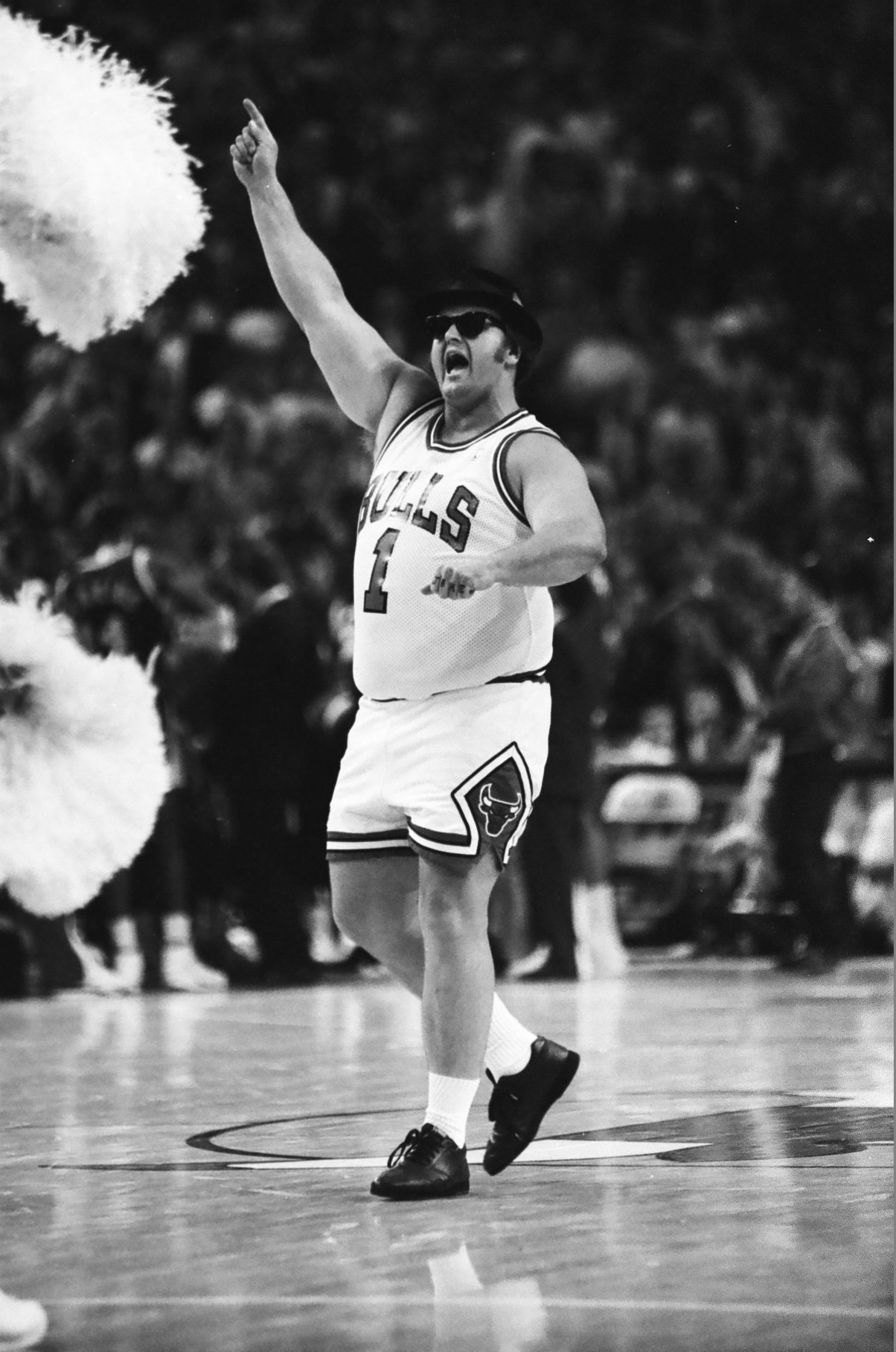

Benny the Bull (played by Dan LeMonnier) keeps the cheers going during a timeout, Chicago, June 5, 1991. ST-50004141-0085, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

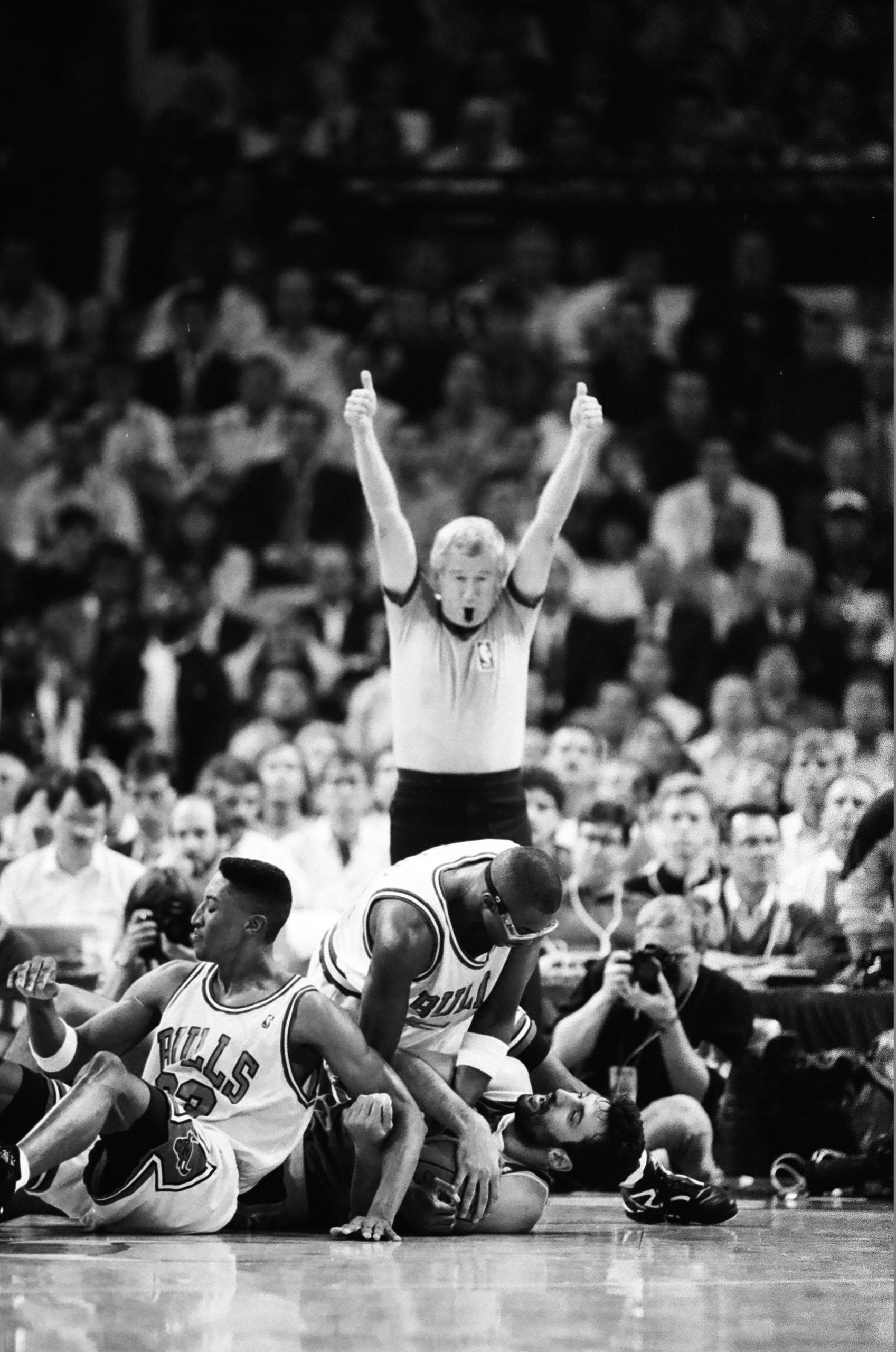

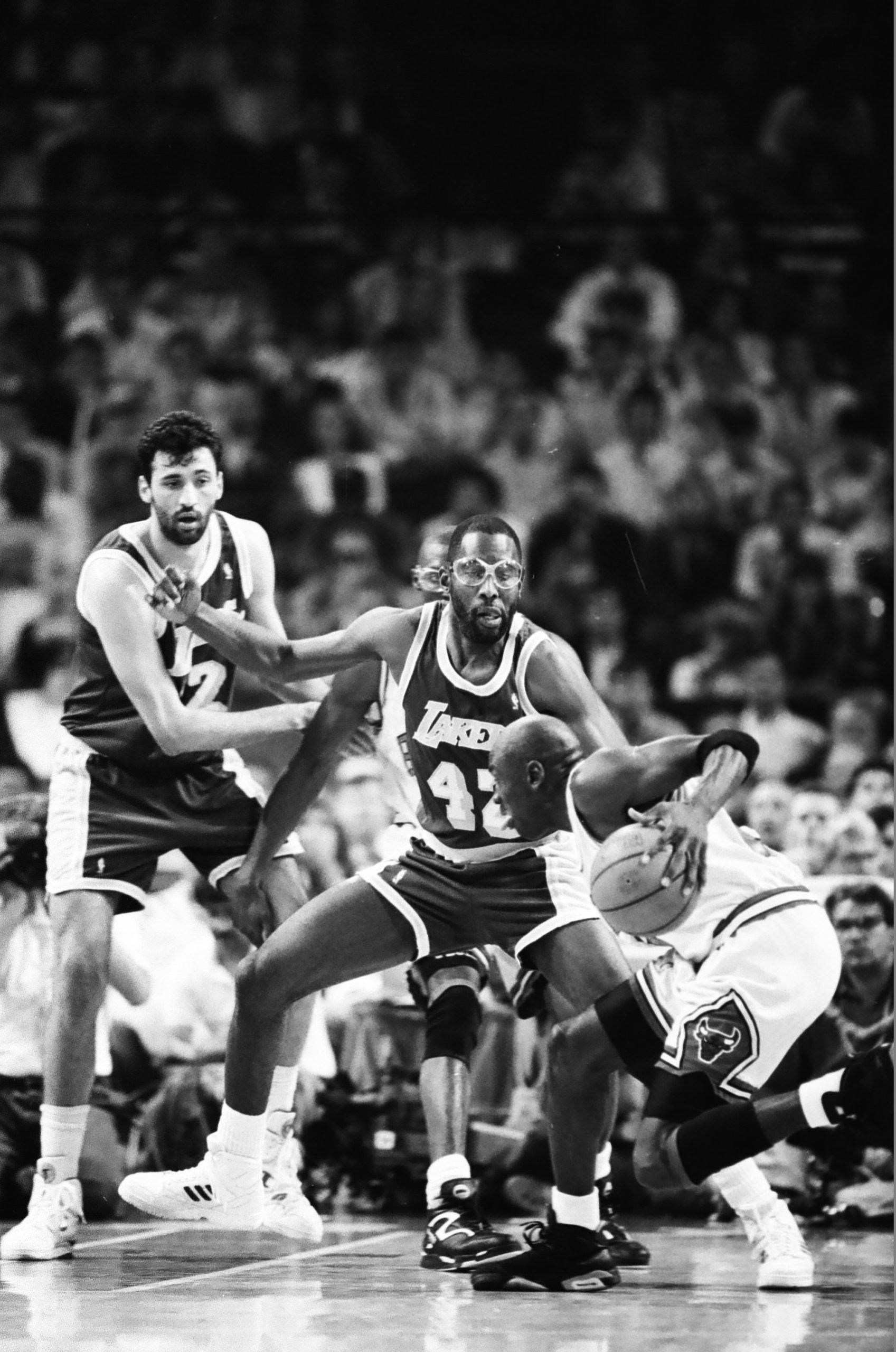

The referee calls a jump ball as Horace Grant (Bulls #54, wearing goggles) and Vlade Divac of the Lakers struggle for possession, Chicago, June 5, 1991. ST-50004141-0011, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Michael Jordan with the ball goes up against Lakers great James Worthy (#42), who was playing limited minutes due to an ankle injury he sustained during game 5 of the Western Conference finals against the Portland Trailblazers, Chicago, June 5, 1991. ST-50004141-0020, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Blues Brother “Joliet” Jake Elwood (played by Fred Bevier) entertains the crowd, Chicago, June 5, 1991. ST-50004141-0081, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

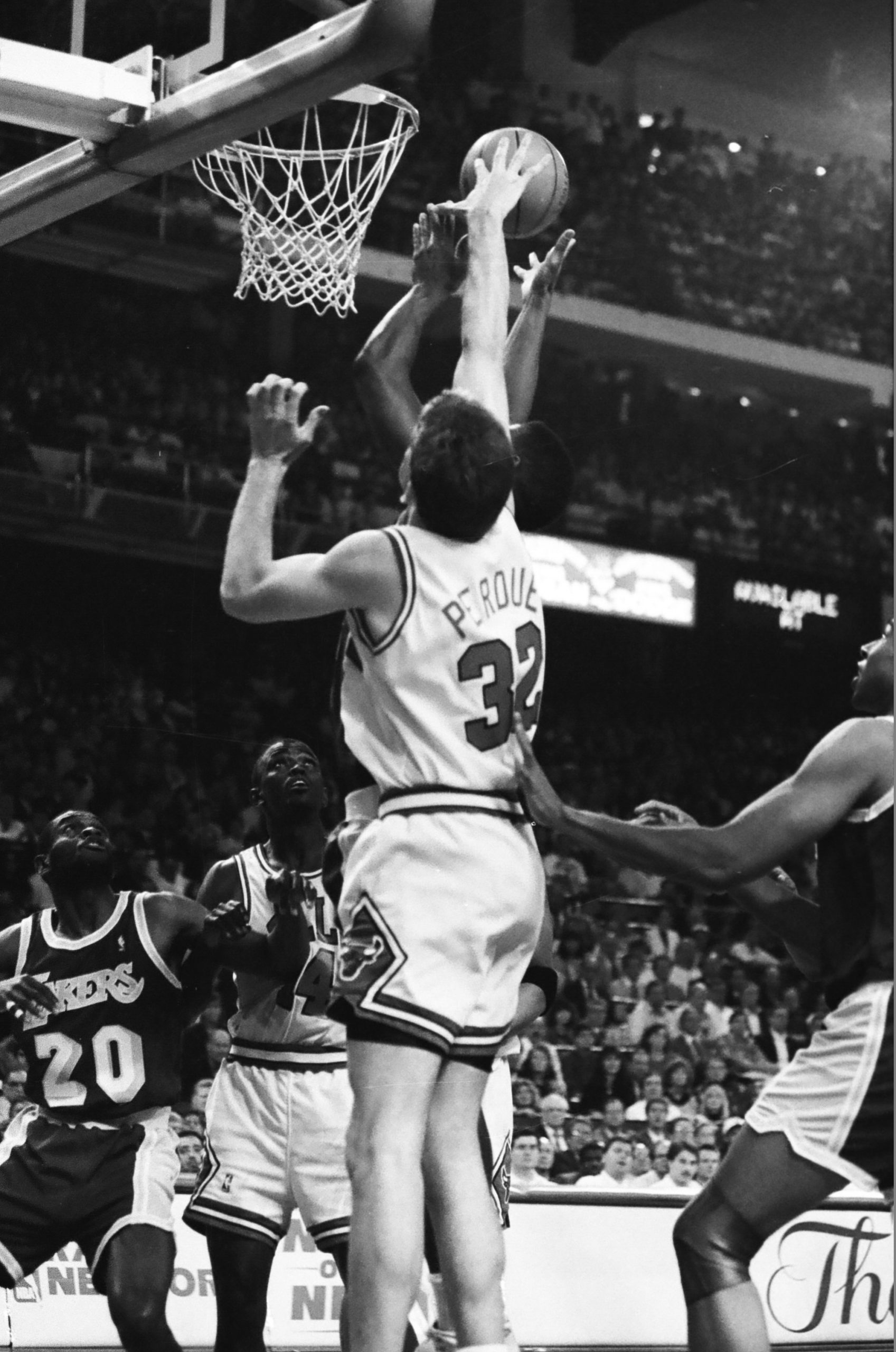

Will Perdue (Bulls #32) goes for the block as Terry Teagle (Lakers #20) and Craig Hodges (Bulls #14) fight for position under the basket, Chicago, June 5, 1991. ST-50004141-0078, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

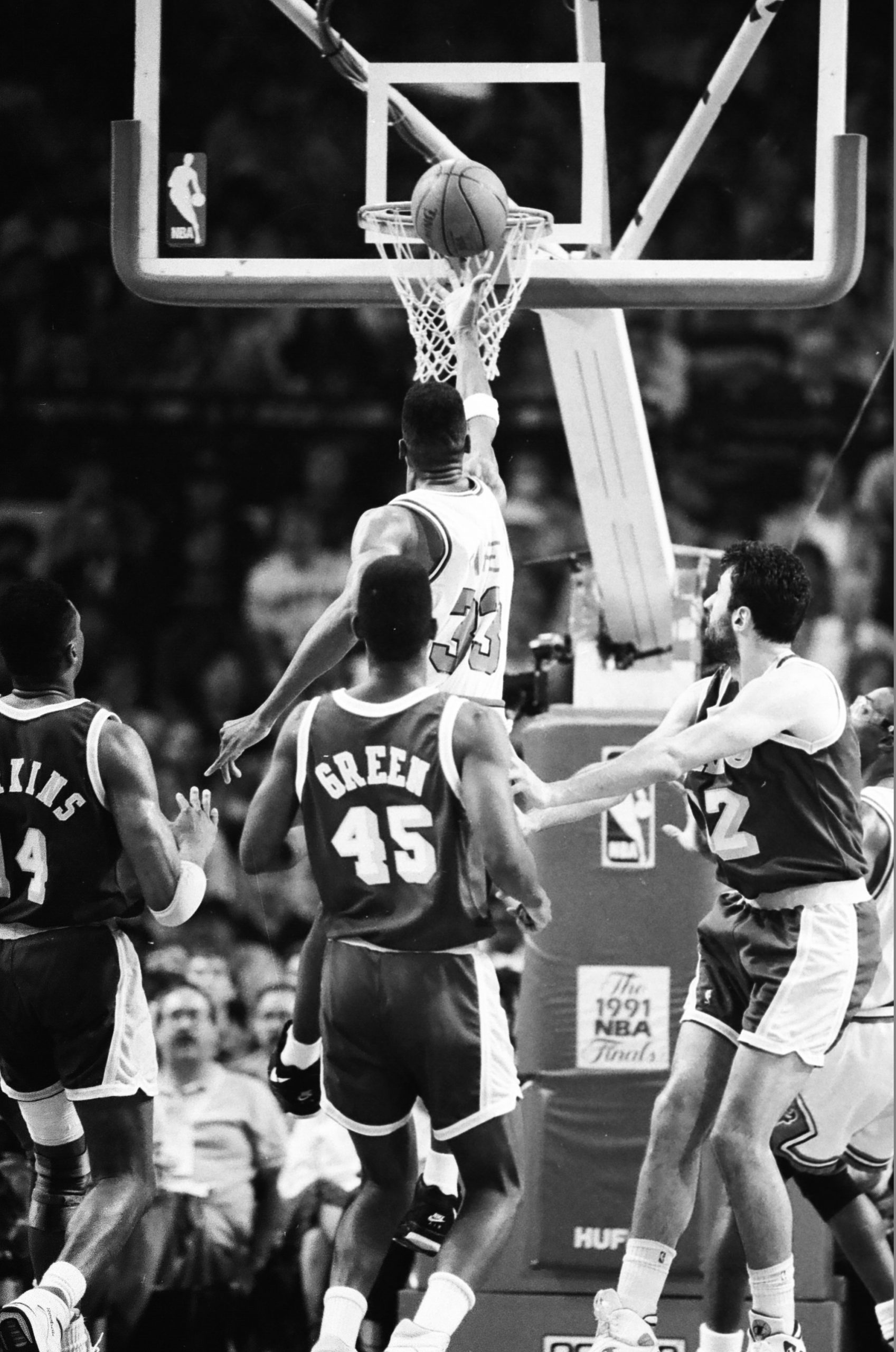

Scottie Pippen (#33) gets past Laker defenders Sam Perkins (#14), A. C. Green (#45), and Vlade Divac (#12), Chicago, June 5, 1991. ST-50004141-0035, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Bulls Coach Phil Jackson on the sidelines during the game. The 1991 championship would mark the first of eleven won by Jackson as an NBA head coach. He would go on to win five as head coach of the Lakers. Chicago, June 5, 1991. ST-50004141-0088, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Additional Resources

- See more images of the Chicago Bulls

- See more images from our Chicago Sun-Times photograph collection

In this blog post, CHM chief historian and Studs Terkel Center for Oral History director Peter T. Alter talks about a major event in Chicago and national labor history that is often excluded from standard historical interpretations. He sits on the website advisory board of the Southeast Chicago Historical Society, which recently launched a new storytelling website.

Content warning: violence, police brutality

The Southeast Chicago Historical Society (SCHS) and the Exit Zero Project recently launched the rich and expansive Southeast Chicago Archive and Storytelling Project. This website has two major parts: the Archive and the Storytelling Project.

The Archive includes over 1,000 items primarily from the collections of the SCHS. The Storytelling Project uses objects, documents, photographs, oral history interviews, and other materials from the archive to develop major story lines about Southeast Chicago. The two story lines currently available are “Mexican-American Journeys” and the “Memorial Day Massacre.” Two more storylines are in the works―the “Closing of the Steel Mills” and “Environmental Pollution and Activism in the Region.”

Police confronting strikers outside Republic Steel, Chicago, May 30, 1937. DN-C-8769A, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

Although a major event in Chicago and US history, standard historical interpretations often exclude the Memorial Day Massacre. As part of the Little Steel Strike of 1937, workers struck against Ohio-based Republic Steel for better treatment and working conditions and higher wages. Republic had a mill located on Chicago’s Southeast Side. Company management planned to break this strike with replacement workers and, ultimately, violence.

On Sunday, May 30, 1937, striking Republic workers and their allies attempted to set up a picket line in the prairie in front of the mill. Chicago police, who were already on the scene, responded with guns and clubs, injuring roughly one hundred people and killing ten men: Sam R. Popovich, Earl J. Handley, Kenneth Reed, Hilding Anderson, Alfred Causey, Leo Francisco, Otis A. Jones, Joseph Rothmund, Anthony Taglieri, and Lee Tisdale. Officers claimed they responded to violence with violence to protect the mill and the country from “communists.” A congressional investigation showed the claims of worker violence to be false, and only a small fraction of those there that day held radical left-wing political beliefs.

Protests in support of Republic Steel strikers continued after the Memorial Day Massacre, such as these women picketing at City Hall, Chicago, June 2, 1937. DN-C-8805, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

Protests in support of Republic Steel strikers continued after the Memorial Day Massacre, such as this group of strikers and sympathizers at a Republic Steel rally, Chicago, June 2, 1937. DN-C-8741, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

The Southeast Chicago Archive and Storytelling Project brilliantly tells the “Memorial Day Massacre” story using the scrapbook of Gerry Jolly Borozan as the central artifact. Mrs. Borozan, who was a teenager when the events unfolded, created a scrapbook with newspaper articles, letters, and photographs documenting the Massacre and its aftermath. She eventually donated it to the Southeast Chicago Historical Society. Using the scrapbook, photographs, oral histories, film footage, congressional testimony, and a striking interpretative framework, the story line recounts the events of late May 1937 and its consequences.

A woman and a man look at a sign on an automobile at the Republic Steel strike, Chicago, 1937. CHM, ICHi-076408; Lawrence Jacques, photographer

Users, for example, can learn about the men who perished. The story line includes a Chicago Defender article stating that African American steelworker Lee Tisdale would “go down [in history] as one who gave his life that all workers may be freed from industrial slavery.” Sam Popovich, a forty-five-year-old immigrant from southeastern Europe, died on the field that day after the police clubbed and shot him. Eventually, by 1941, Republic Steel recognized the steelworkers’ right to organize. Anyone interested in the city’s history should definitely visit the Southeast Chicago Historical Society and the Exit Zero Project’s website to learn more.

Additional Resources

- See more images of the Memorial Day Massacre and the continued protests

- Listen to Dr. Lewis Andreas talk to Studs Terkel about being at the Memorial Day Massacre

In 1889, an international group of socialist party members and trade union representatives designated May 1 as a day in support of workers in commemoration of the 1886 Haymarket Affair in Chicago and the subsequent trial and executions. Since then, May Day (also called Workers’ Day or International Workers’ Day) has been celebrated in many countries and recognizes the historic struggles and gains made by workers and the labor movement.

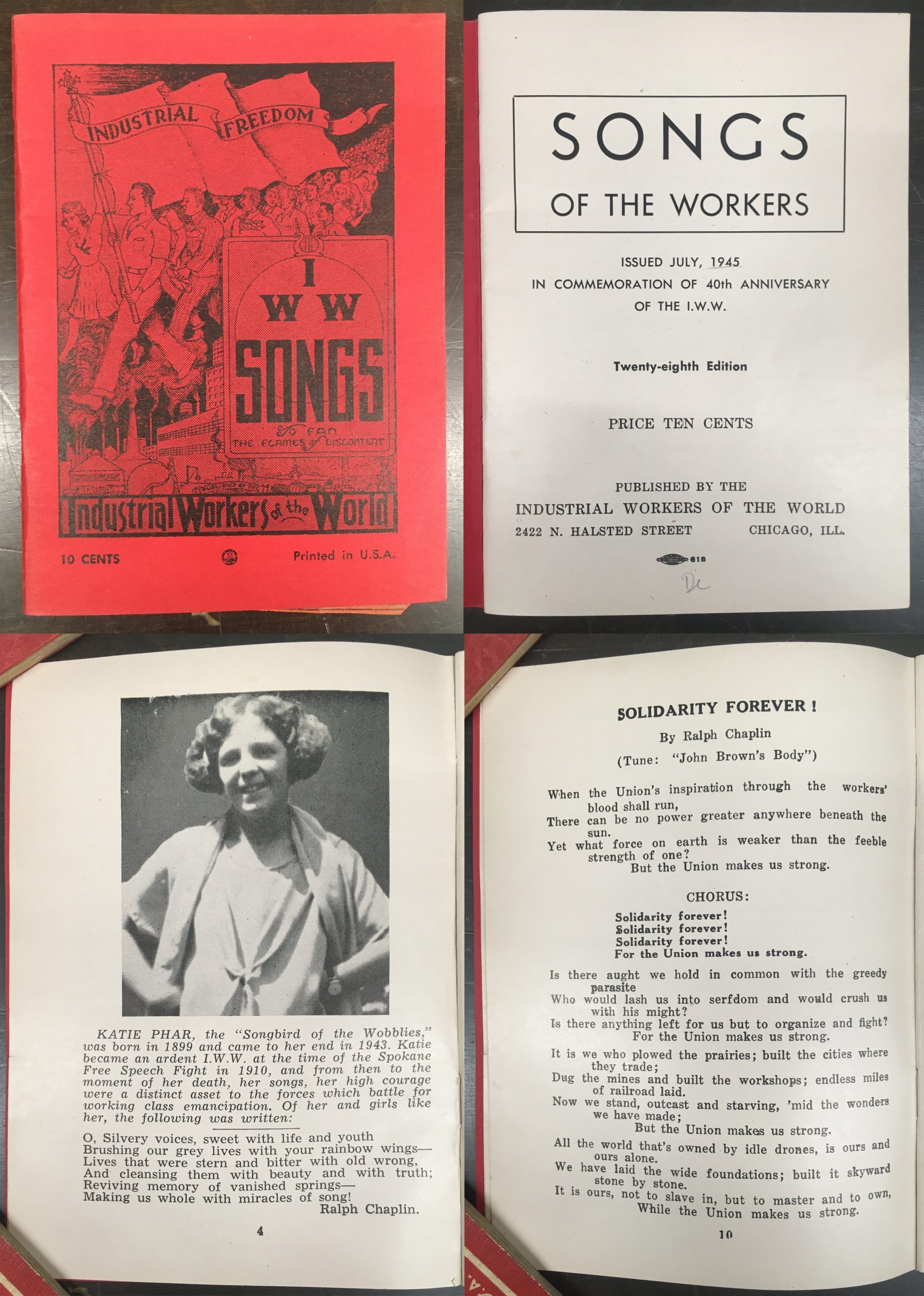

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Chicago was a hotbed of activity for the labor movement. As such, the city was a creative center for working-class protest songs and poetry from about 1865 to 1920. Labor publications and organizations featured thousands of compositions by workers and their allies as they sought to rally support. Songs appeared in newspapers, songbooks, and posters, and at rallies, strikes, meetings, and social events. Literary and musical influences included folksongs, hymns, Civil War music, poetry, and literature. The majority offered social criticism and a prolabor message, but also addressed specific issues including wages, hours, strikes, among others.

After 1900, mainstream unions moved away from broad-based social reform, as well as cultural activities such as music and poetry. Additionally, workers began seeking their entertainment from the burgeoning popular culture industry. Radicals, however, maintained and refined the labor song tradition, producing important work. The Chicago-based Industrial Workers of the World (“Wobblies”) proved adept at the craft, publishing IWW songbooks that were often sold at protests for a few cents apiece. Singing at union gatherings would continue into the 1940s, as workers still sang Chicago “Wobbly” Ralph Chaplin’s famous 1915 labor hymn: “Solidarity Forever! For the Union makes us strong.” The days when labor songs permeated the labor movement, however, had passed.

Learn more about the history of labor songs in Chicago in our Encyclopedia of Chicago entry.

Image: Cover and pages from the Industrial Workers of the World songbook Songs of the Workers, 28th ed., July 1945. CHM Abakanowicz Research Center, M1664.L3 I6. Photographs by CHM staff.

Grant to Support Upcoming Exhibition, “City on Fire: Chicago 1871”, to Commemorate the 150th Anniversary of the Great Chicago Fire

The Chicago History Museum this month received a $376,503 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) in the public humanities category to support upcoming exhibition, City on Fire: Chicago 1871. The family friendly exhibition commemorates the 150th anniversary of the Great Chicago Fire and will guide guests through the crucial events and conditions before, during, and after the fire – many of which draw striking comparisons to today’s social climate. City on Fire: Chicago 1871 opens to the public on October 8, 2021.

“The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 is part of the fabric of Chicago, shaping the city’s strength and resilience that defines us today,” said Donald Lassere, president and CEO of the Chicago History Museum. “We are grateful to NEH for allowing us to further our mission to share Chicago stories by making this pivotal history available for visitors of all ages and interests.”

The Chicago History Museum is one of 225 organizations that received grants from NEH, all directly supporting the preservation of historic collections, humanities exhibitions and documentaries, scholarly research, and curriculum projects. NEH grants totaled $24 million across the country. This grant will also support public programs and educational opportunities related to City on Fire: Chicago 1871.

Created in 1965, NEH is an independent federal agency and one of the largest funders of humanities programs in the United States. NEH awards grants to top-rated proposals examined by panels of independent, external reviewers.

For more information on City on Fire: Chicago 1871, please visit: https://www.chicago1871.org/