Latest Posts

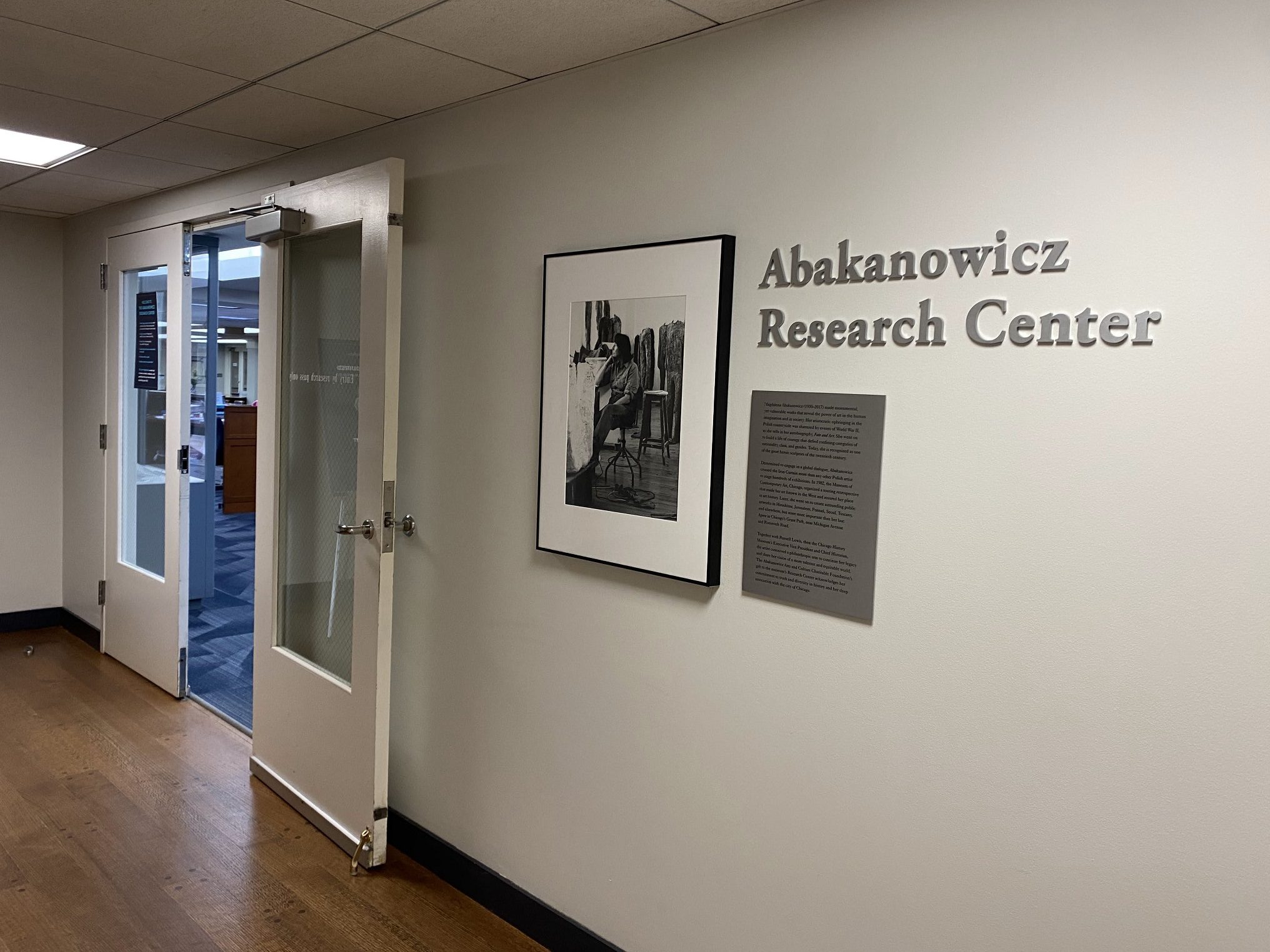

In our latest blog post, CHM director of research and access Ellen Keith gives an update on what’s new at the Abakanowicz Research Center.

Here at CHM, we distinguish between museum collections and research collections. In shorthand, museum collections are three-dimensional artifacts. They may be on exhibit or carefully stored. Research collections are two-dimensional and include published material, photographs, maps, architectural drawings, and archives and manuscripts. One of the wonderful things about research collections is that they can be used by the public.

Where does this happen? The Museum’s Research and Access Department serves these collections through the Abakanowicz Research Center (ARC) on the third floor of the Museum. It’s free and open to the public and no special credentials are required to visit, just an interest in Chicago history.

If you’re already a fan of the ARC, you may know that we’ve made some changes since March 2020. We’re currently requiring appointments for weekdays. Researchers make appointments online and dates are available a month at a time. During the height of the pandemic, we suspended Saturday hours, but last fall, we reopened on Saturdays from 10 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. We’re open Saturdays after Labor Day through Memorial Day weekend, and as that’s the day with the longest hours, we have no capacity limits and no appointments required. Come and see us on a Saturday!

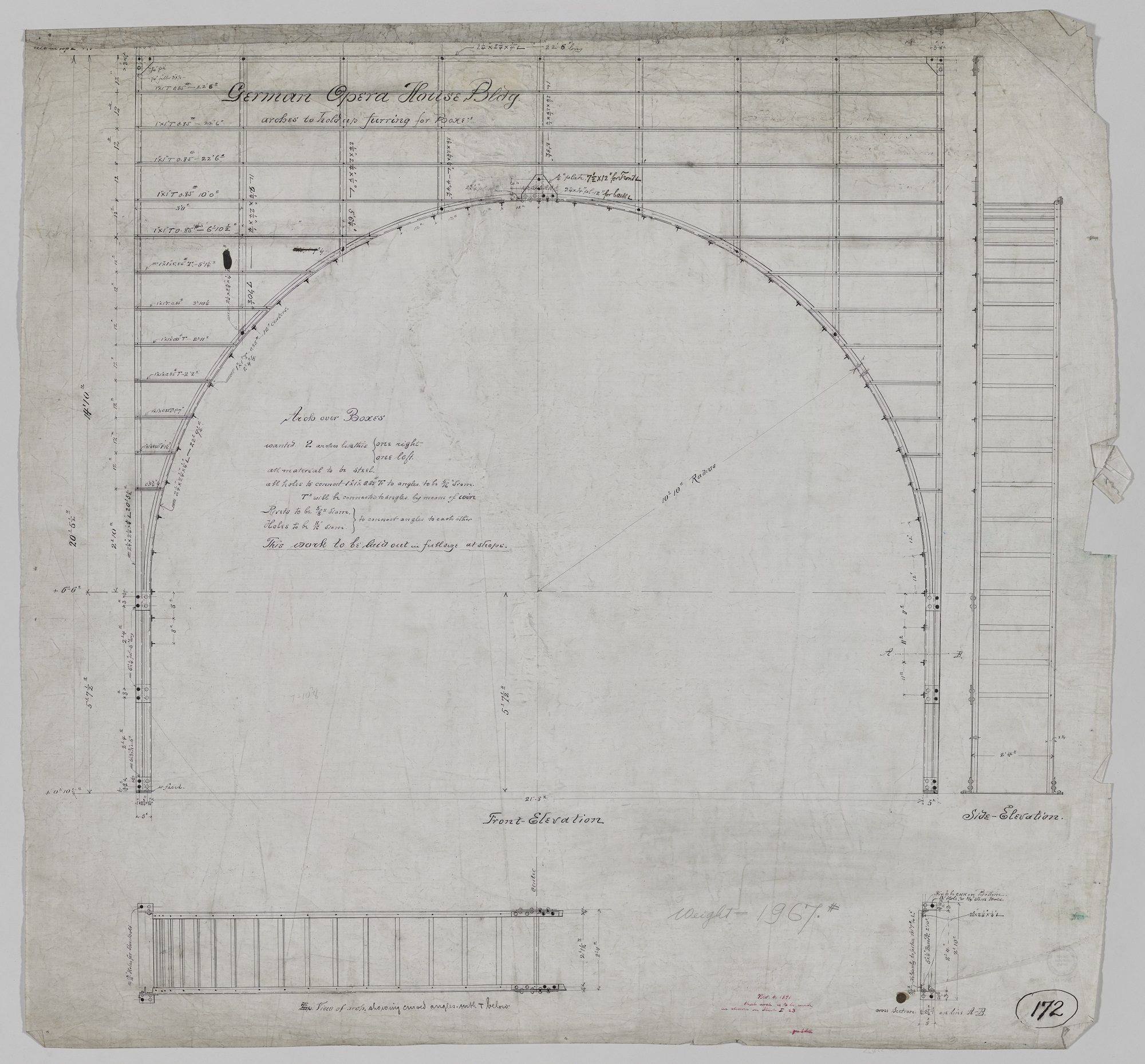

Architectural drawing of the Schiller Theater Building/Garrick Theater by Louis Sullivan and Dankmar Adler of Adler & Sullivan for the German Opera Company, Chicago, c. 1920. CHM, ICHi-178195

We have an impressive number of published materials, photographs, architectural drawings, and archives and manuscripts. The best place to start a search for these is ARCHIE, our online catalog. The majority of these resources have to be accessed in-person, but, where possible, we’ve provided links to digital versions.

Two examples from our menu collection. Left: The Thanksgiving dinner menu from Clifton House, November 25, 1858. Right: A Sunday menu from Foster House, February 24, 1856.

One staff project during the pandemic closures of March to July 2020 and November 2020 to March 2021 was searching HathiTrust and the Internet Archive for freely available full-text of material in our holdings. And bonus, sometimes what’s online extends beyond our holdings. For example, our print holdings for the Chicago Department of Health report are 1879–93, but the HathiTrust link in our catalog record has 1867–1940!

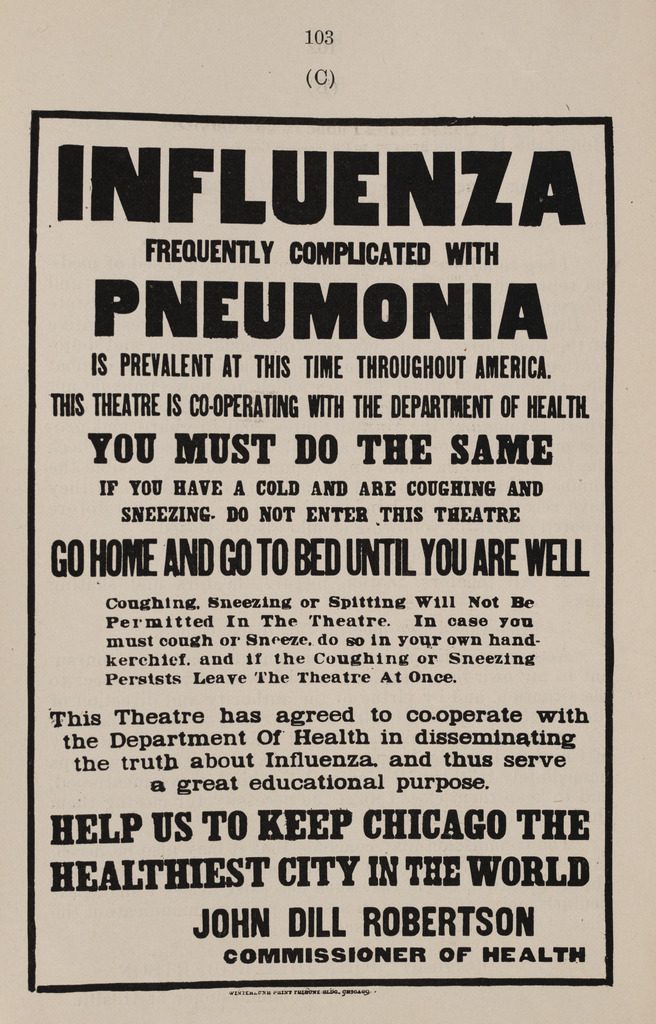

A reproduction of an announcement made by a Chicago theater warning against symptoms of influenza published in A report on an epidemic of influenza in the city of Chicago in the fall of 1918 by John Dill Robertson, MD, Commissioner of Health, published by the Department of Health in Chicago, 1918. CHM, ICHi-176190

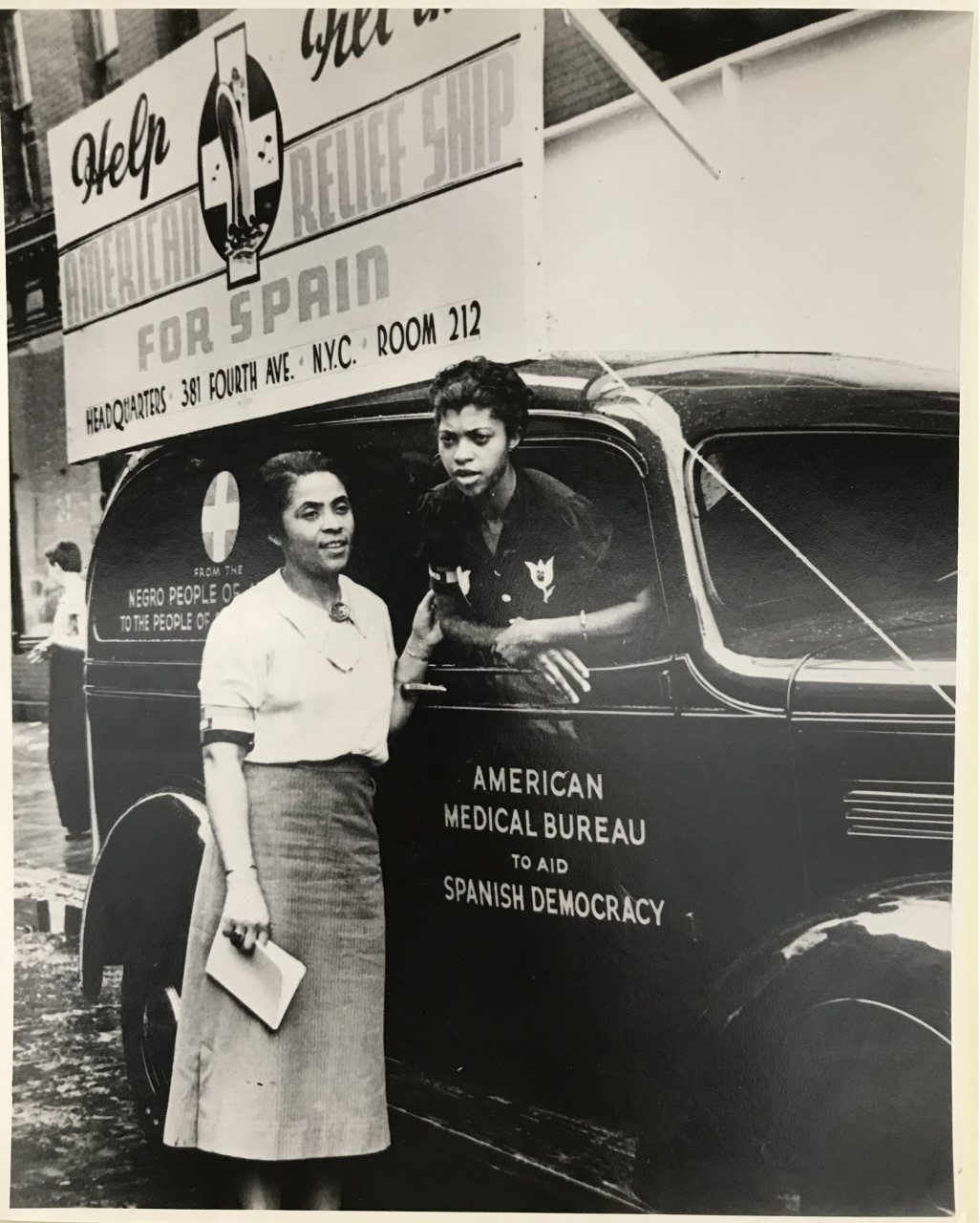

And (drumroll please), after a much-needed renovation of our collections storage facility, our more than 20,000 linear feet of archives and manuscripts are available again! The collections include records of organizations, like the African American Police League records, and papers of individuals like the Thyra Edwards papers.

Journalist Thyra Edwards wrote for several Black newspapers, including the Chicago Defender. In 1938, Edwards (in vehicle) organized an ambulance tour of the US to raise funds for Spanish democracy during the Spanish Civil War.

We may be biased but this is an amazing collection of archival material, spanning from the French America collection of manuscripts, 1635–1817 to the 21st century with the Center on Halsted records, 1999–2007.

Questions? Contact us at research@chicagohistory.org and be prepared for our response to white gloves inquires.

Forty years ago today, a series of grim deaths in the Chicago metropolitan area gripped the nation, changing how American consumers buy over-the-counter medicine and the way public health officials respond to crisis situations.

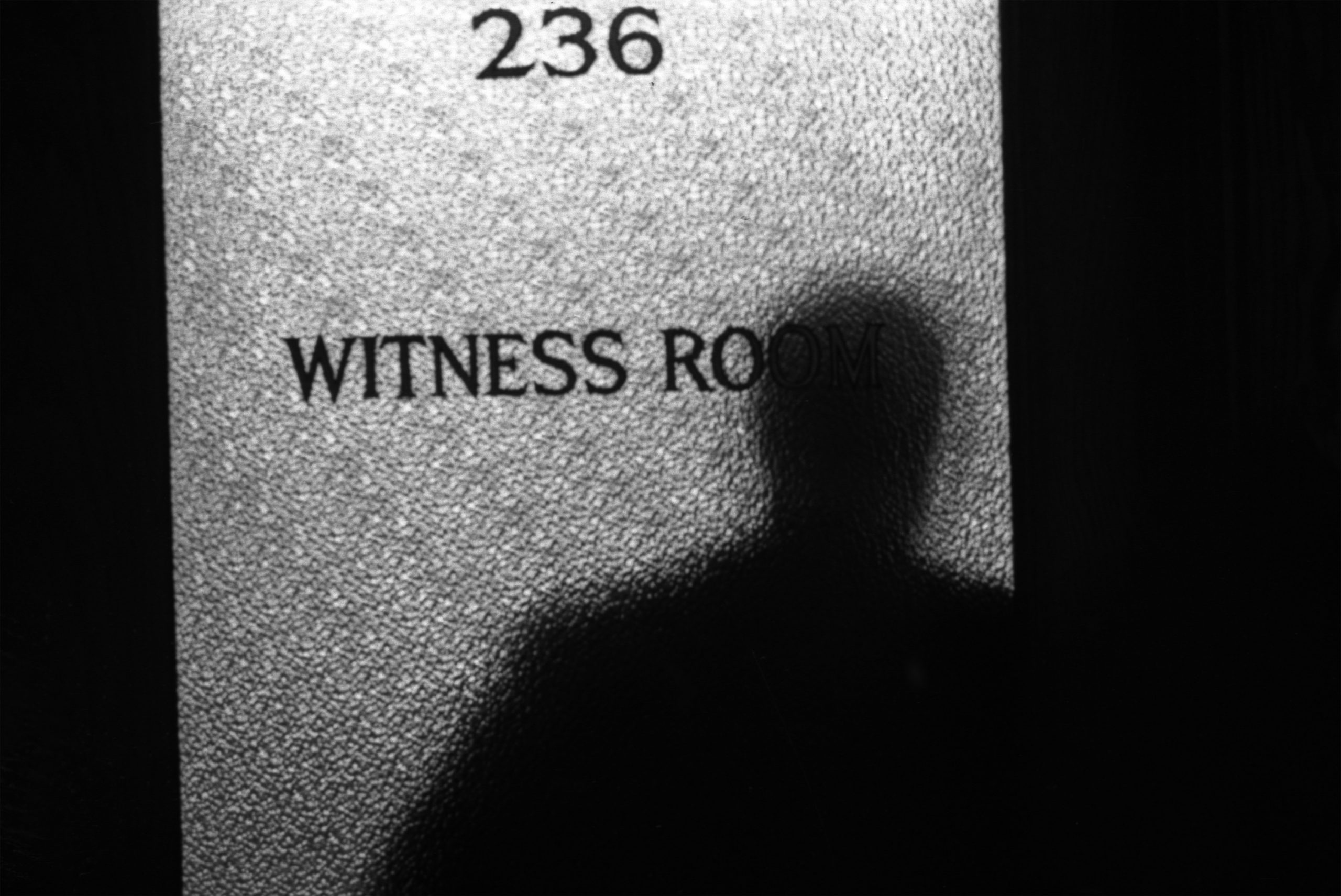

The Chicago Tylenol murders, as they’ve come to be known, began in the morning hours of September 28, 1982, with a 12-year-old Elk Grove Village resident named Mary Kellerman, who was given a Tylenol tablet by her parents in response to complaints of a sore throat. No one could have imagined that within a few hours, Mary would be dead, due to the medication being tainted with a lethal substance. Later that same day, Adam Janus, a postal worker in Arlington Heights, died after taking similarly doctored Tylenol. In a grim twist of fate, his brother and sister-in-law would die after ingesting the same tainted medication they found in Adam’s home. They were there to support and share company with family members after hearing about Adam’s passing. Following these deaths, three more casualties (a total of seven) linked to tainted medicine were reported, two in the suburbs and one in Chicago.

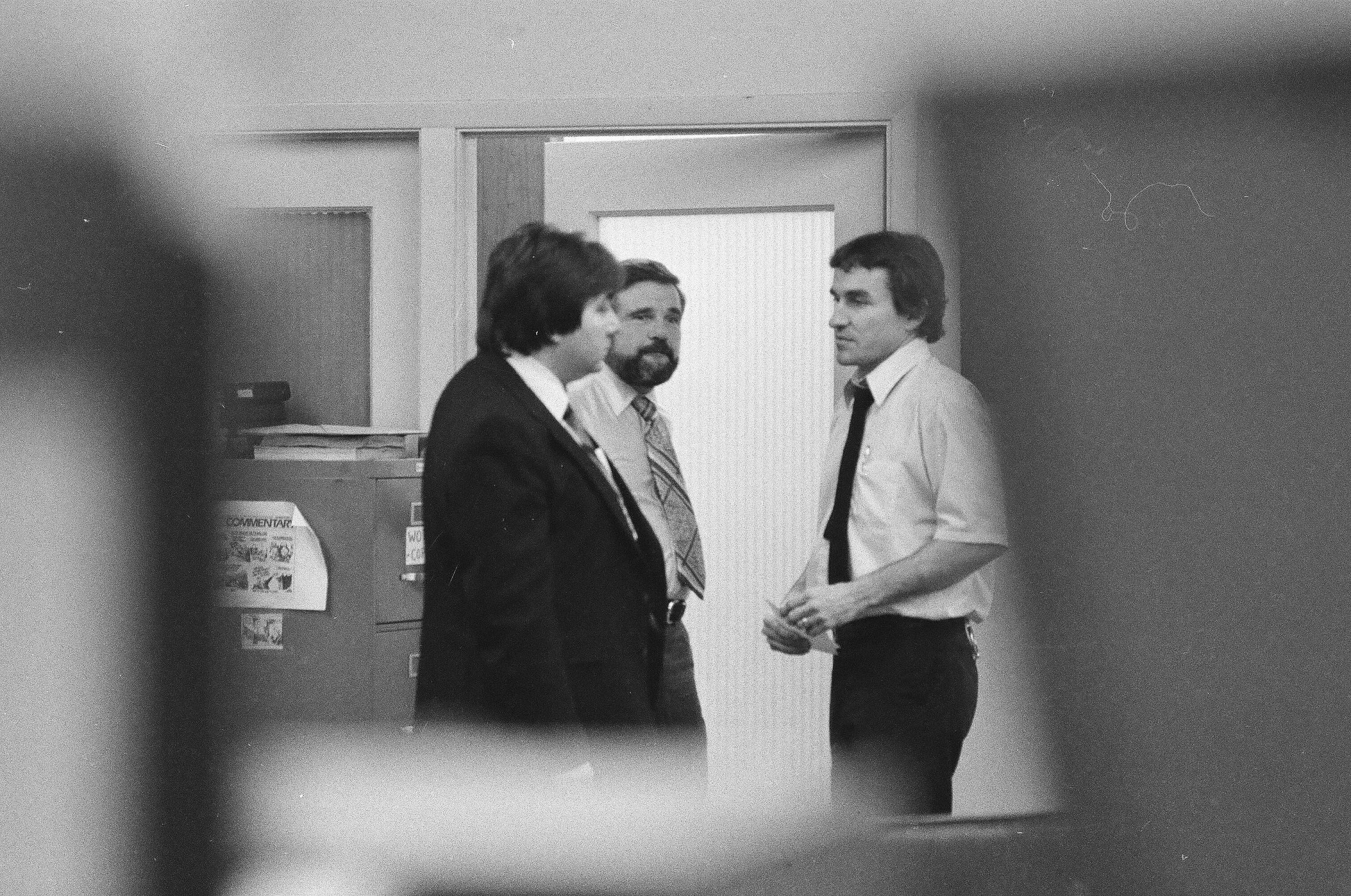

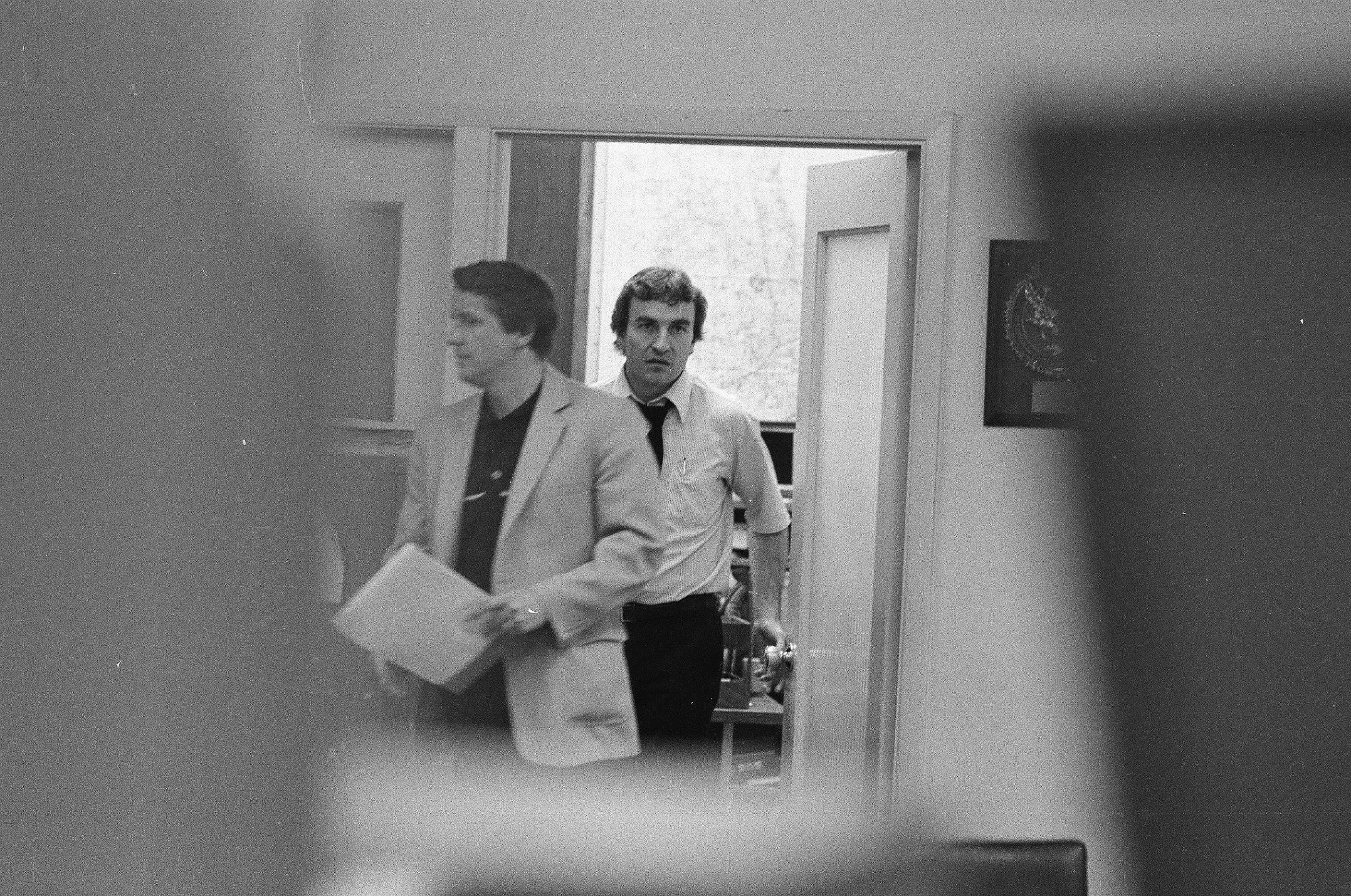

Investigators at the Attorney General North West Criminal Investigation Center at River Road and Rand Road, Des Plaines, Illinois. December 2, 1982. ST-20001914-0009, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM; photograph by Gene Pesek

The mysterious deaths immediately raised red flags for local officials and health care providers who responded to help with the investigation, given the peculiar nature of the casualties and the alarming rate at which they were spreading. It became apparent that as much as this was a broad-ranging murder investigation, it would also be a public health crisis. It was quickly established that the link among all the victims was consumption of Tylenol tablets shortly before death, and authorities sent off medication bottles found in homes of the deceased for testing. When the test results came back, it was found that the acetaminophen pills in these containers had been swapped with tablets containing lethal doses of potassium cyanide.

Investigators at the Attorney General North West Criminal Investigation Center at River Road and Rand Road, Des Plaines, Illinois. December 2, 1982. ST-20001914-0009, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM; photograph by Gene Pesek

Within 48 hours, Mayor Jane Byrne, with the cooperation of local law enforcement, health officials, and universities, had all Tylenol products pulled from local grocers and pharmacies and shipped off to various laboratories in the area for integrity testing. Area residents were instructed to dispose of any Tylenol products they had at home, and the drug manufacturer issued a nationwide recall. This mass panic caused a considerable amount of chaos in the area and across the nation, with many towns going as far as canceling Halloween trick-or-treating for fears of candy tainted in the same way as the medication falling into the hands of children.

To this day, the perpetrator of the murders has not been identified or apprehended by authorities. A man from New York, James Lewis, claimed responsibility for the events and demanded $1 million dollars from Tylenol’s parent company in exchange for stopping the killings. However, it was quickly established that he could not have been the person responsible, and he served 13 years in prison for extortion.

Beyond being a grim part of the city’s history, this incident had a profound impact on the US drug industry. In 1983, Congress passed the “Tylenol Bill,” which made it a felony to tamper with consumer products. In 1989, the FDA updated their policies to make medications more tamperproof, requiring tamper-evident seals on all over-the-counter medications and the eventual transition in manufacturing to more modern “caplets” that are harder to tamper with than older medications.

September 24, 1969, marked the beginning of one of the most infamous trials in U.S. history for eight (later seven) activists linked to the protests that took place in response to the 1968 Democratic National Convention, held in Chicago at the International Amphitheatre on August 26‒29.

Eight defendants, Rennie Davis, David Dellinger, John Froines, Tom Hayden, Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, Lee Weiner, and Bobby Seale, were charged by the federal government with several accusations that included conspiracy and crossing state lines to incite riots.

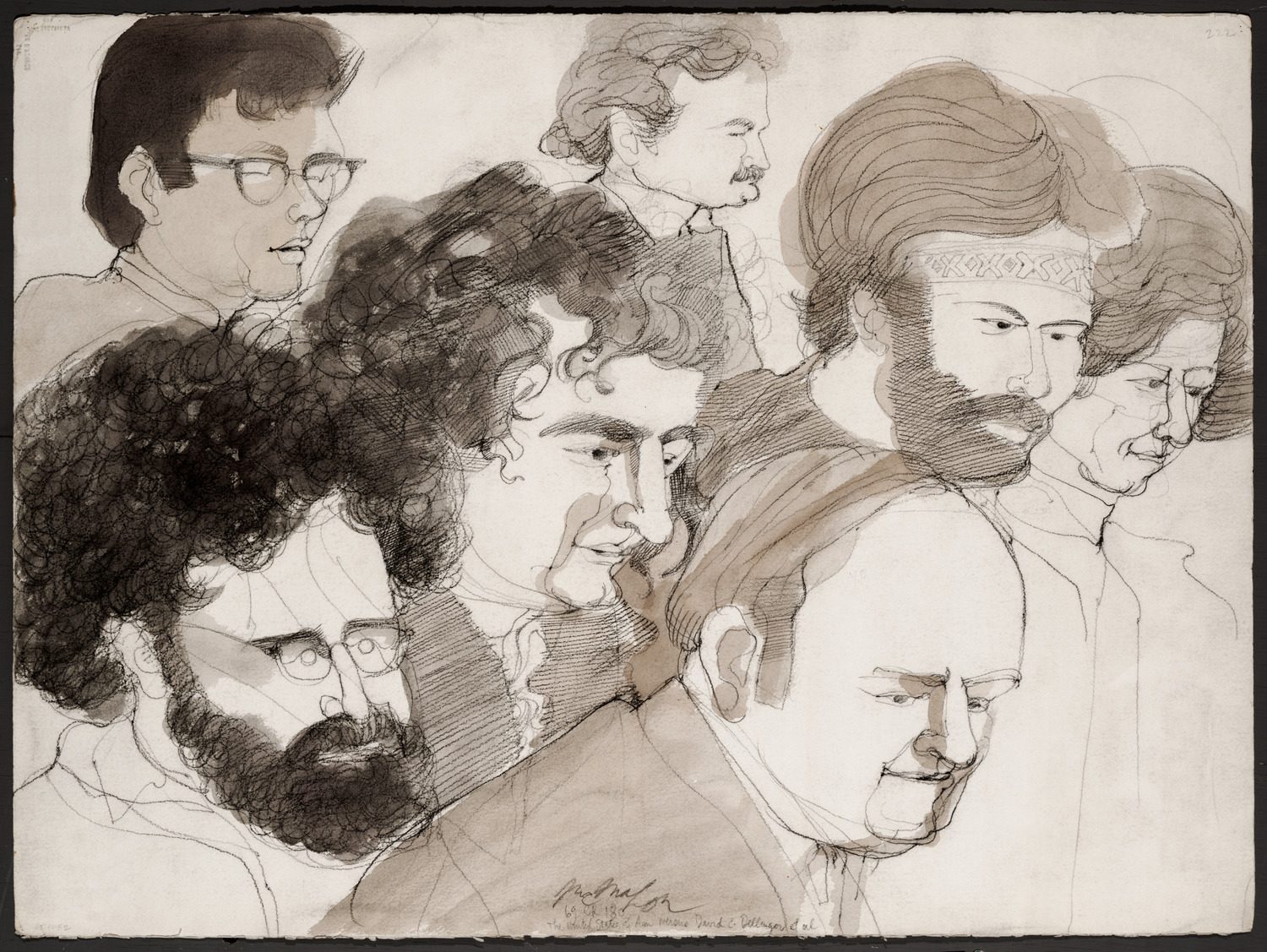

Profile view of all the Chicago Seven Trial defendants, 1969‒70. CHM, ICHi-051727; Franklin McMahon, artist

In the summer of 1968, more than 10,000 people came to Chicago ready to protest the wildly unpopular Vietnam War, which had been raging for over a decade. The protest was originally planned to be a nonviolent gathering at Lincoln Park. But it expanded over multiple days to street protests and demonstrations in Grant Park, which quickly turned chaotic when protestors were met by leagues of uniformed CPD and National Guard officers, armed with antiriot equipment and tasked to maintain order. The chaos culminated on August 28, which came to be known as the “Battle of Michigan Avenue.”

View of protesters at the 1968 Democratic National Convention, marching down Michigan Avenue, 1968. CHM, ICHi-093520; Stephen Deutch, photographer

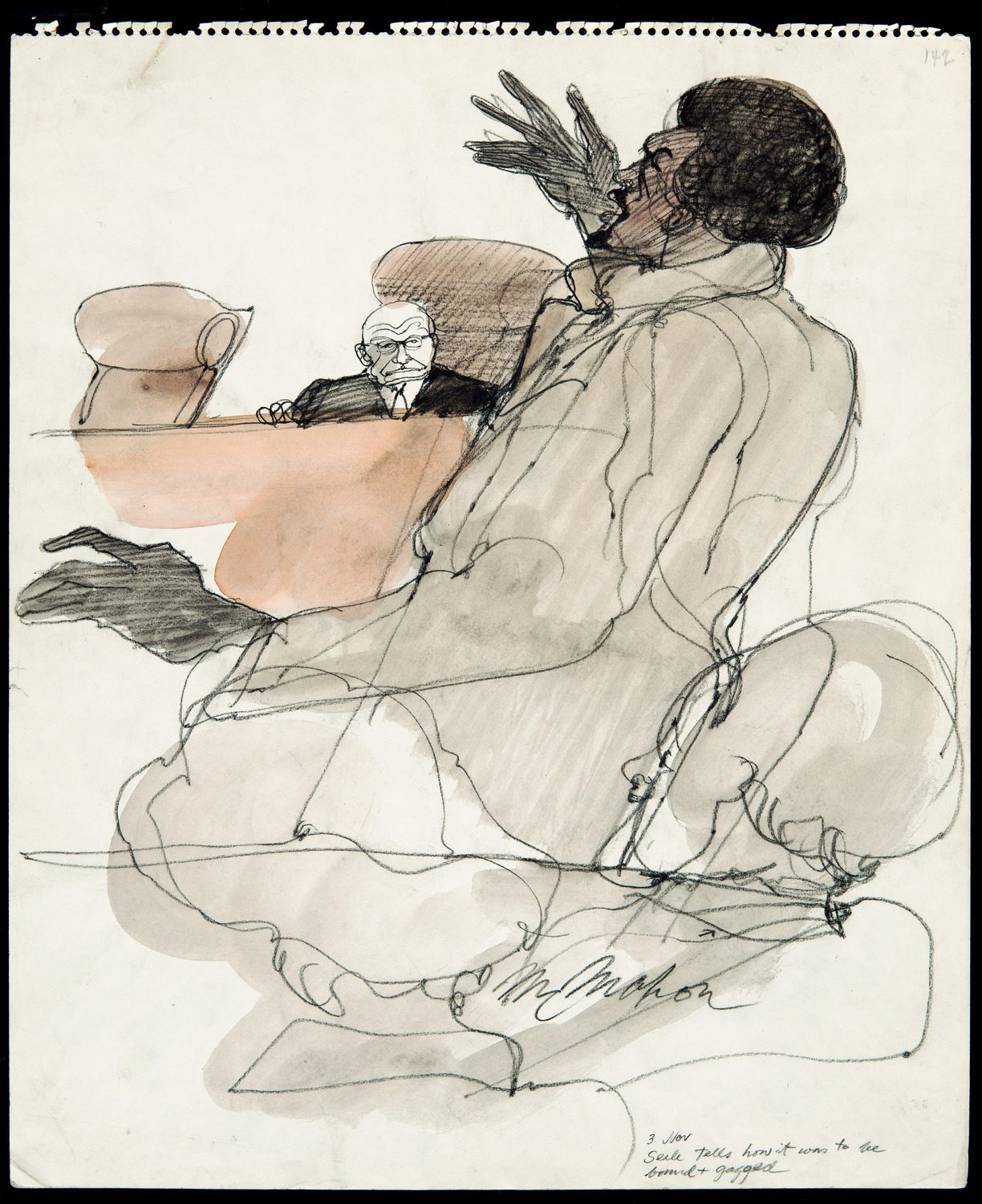

An extensive government investigation followed the unrest, and ultimately, a year later, charges against the “Conspiracy 8” would be filed, as the federal government sought to make an example of these protestors and to test the federal antiriot law passed in 1968, which made it illegal to cross state lines to incite a riot. The eight men charged were not chosen at random. Each one had a history of organizing against the war in one way or another, with the most prominent defendant being Bobby Seale, a cofounder of the Black Panther Party. During the trial, Judge Julius Hoffman ordered him to be restrained, bound, and gagged to his chair after he requested to represent himself. Not long after, Seale was removed from the case, and had a separate trial, turning the “Conspiracy 8” into the “Chicago 7.”

Bobby Seale telling Judge Julius Hoffman how it felt to be bound and gagged at Chicago Eight Trial, November 3, 1969. CHM, ICHi-051750; Franklin McMahon, artist

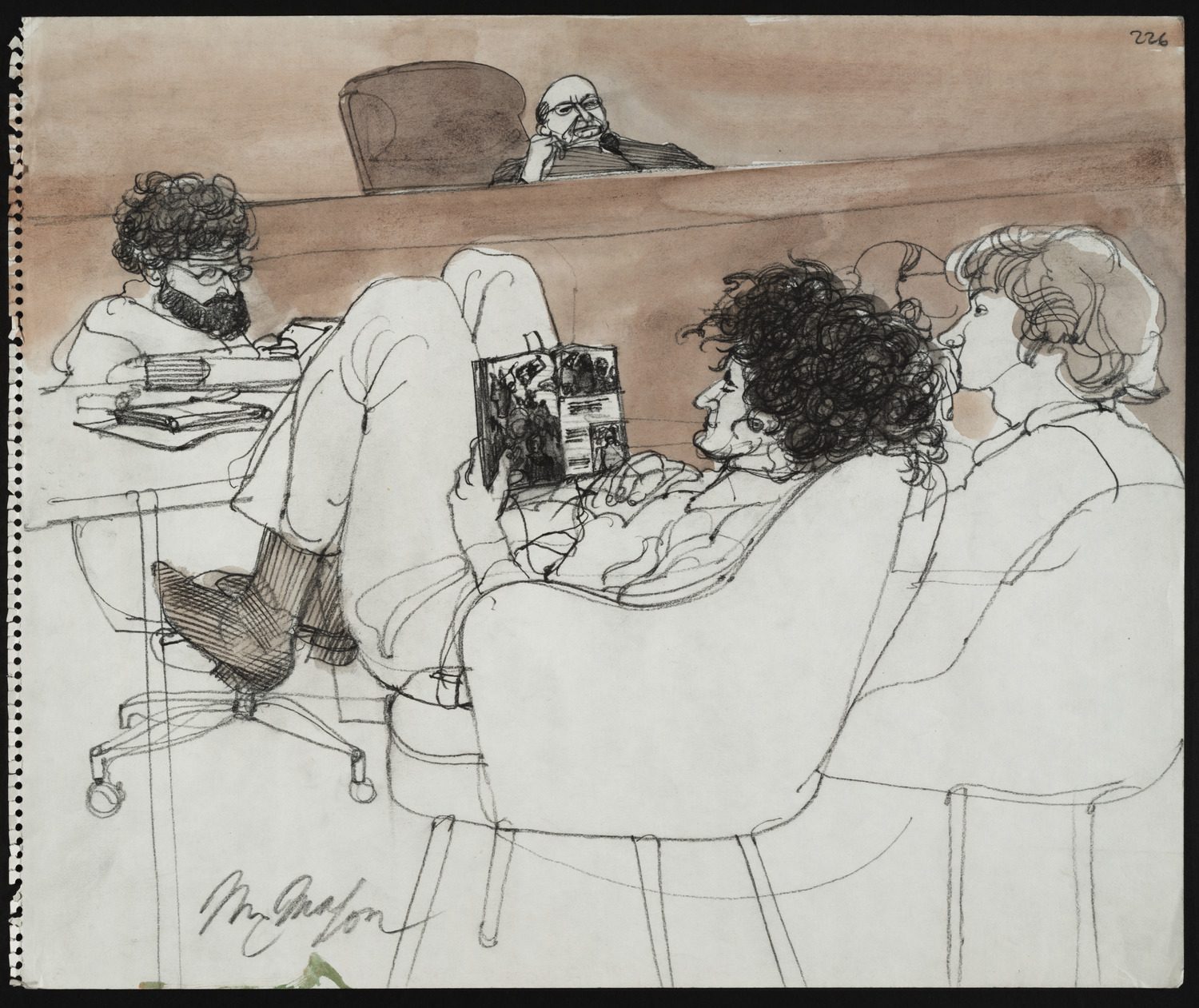

The jury for the Chicago 7 was composed of two white men and ten women, two of whom were Black, and the rest white. The demeanor of the defendants, especially that of Abby Hoffman was anything but formal, with vibrant attire, including leisure wear, and colorful language peppered throughout the trial, which was recorded by reporters and courtroom sketchers, as cameras were not allowed inside.

Abbie Hoffman reading a magazine at the Chicago Seven Trial, 1969‒70. CHM, ICHi-051213; Franklin McMahon, artist

Beyond being a legal case, the trial of the Chicago 7 was a cultural moment in the 1960s, where generational ideals were clashing in the public eye. The seven defendants represented a generation of activists, who were suspicious and unsupportive of a foreign war, and a judge and legal system that embodied what younger Americans perceived to be a status quo that had gone unchallenged and unchecked for far too long.

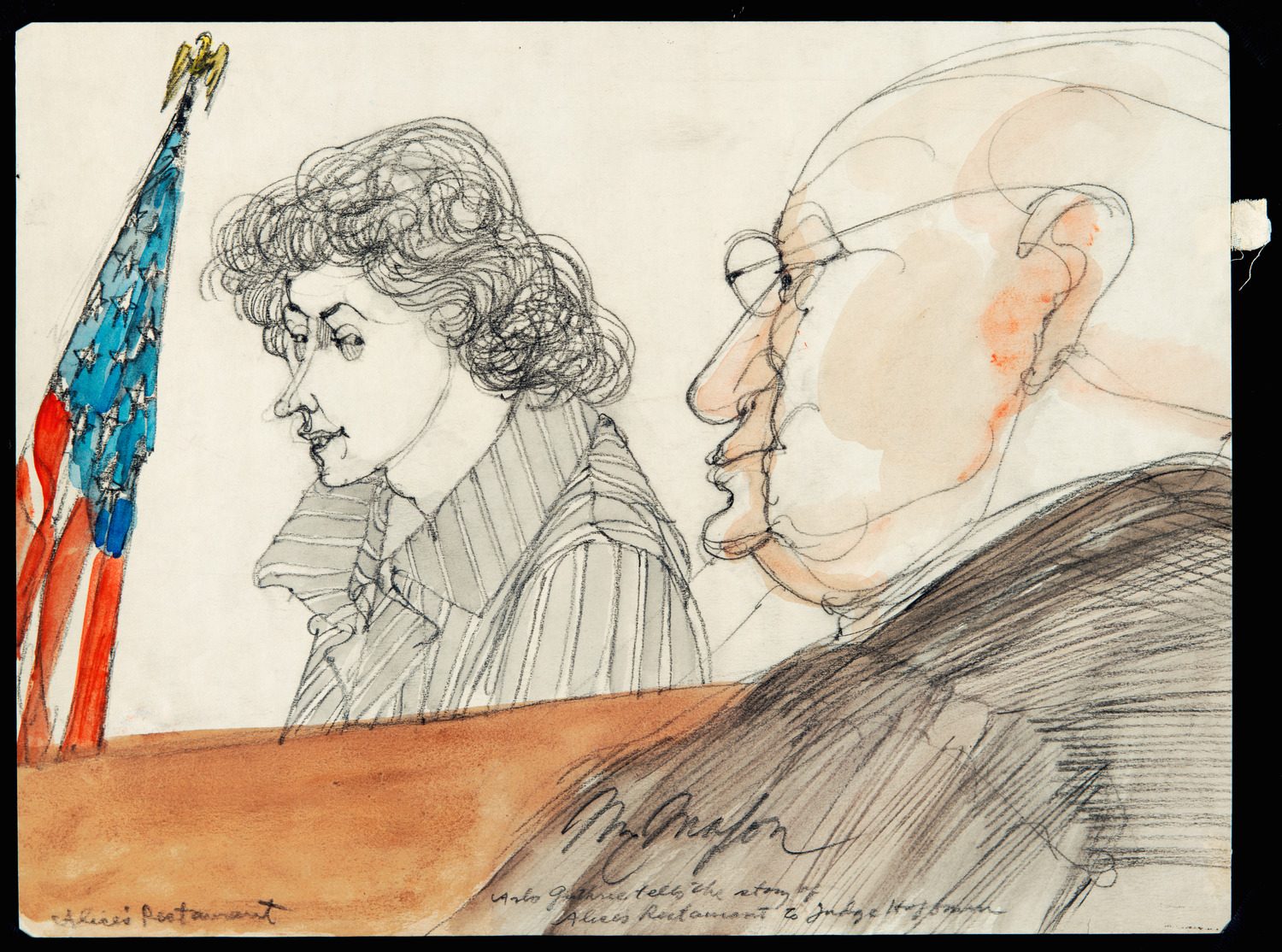

Arlo Guthrie telling story of Alice’s Restaurant to Judge Julius Hoffman at Chicago Seven Trial, 1969‒70. CHM, ICHi-051733; Franklin McMahon, artist

Ultimately, all seven defendants were acquitted of conspiracy charges, but five of the seven were charged with crossing state lines to incite riots and were convicted with five-year prison sentences and hefty fines. (Seale had also received a four-year sentence in his own trial.) A couple years later, all the convictions would be tossed by an appellate court, recognizing Judge Hoffman’s disdain for the defendants. The story of the Chicago 7 was serialized by Netflix in 2020 and continues to be one of the most important courtroom sagas in Chicago and U.S. history.

In addition to having the trial papers and notes from Judge Hoffman in our collection, in 2007, CHM acquired 483 courtroom sketches from the trial by famed news artist Franklin McMahon.

Further Resources

- See more of Franklin McMahon’s courtroom sketches

- See more images of the 1968 Democratic National Convention

- Studs Terkel’s 1968 Interview with Hoffman, Seale, and Dellinger

- I WAS THERE: The 1968 Democratic National Convention Oral History Project

- Chicago ØØ: The 1968 DNC Protests, a virtual reality experience

- Chicago: Law and Disorder Google Arts & Culture Story

- “The Park is Ours” by Brian Mullgardt in Chicago History

- The Trial of The Chicago 7: The Official Transcript

Rebekah Coffman joined the Chicago History Museum in May 2022 as the new Curator of Religion and Community History. In this blog post, she talks about her path to CHM and how she approaches her work.

In my first few months at CHM, I have been able to jump into my position with both feet while supporting research across a number of current initiatives exploring the rich and layered histories of Chicago. More importantly, I’ve been questioning what it means to even be a curator of religion and community. These two topics can feel so broad it can be hard to define them. Some days, it’s a boundless opportunity. Others, it’s a grueling challenge. Community is messy, and our very human experiences of how we come together have layers of complexity and challenges.

Rebekah handling archival material in storage. All photographs courtesy of Rebekah Coffman.

My path to CHM has been a bit winding, with my professional experiences crossing boundaries between museum, education, and community spaces. Having faith leaders for parents, my childhood was embedded with questions of how everyday life encounters sacredness. As I entered early adulthood, I found myself dissecting the intersections of representation and religious identity in my undergraduate studies. I realized how much of our daily lives were saturated—materially and visually—in spiritual heritages and how these references could be distorted to create division or centered to find common ground and mutual understanding. As part of an interfaith religious scholars program, I read Eboo Patel’s Acts of Faith: The Story of an American Muslim, the Struggle for the Soul of a Generation and found resonance in conversations of peaceful plurality. I used this as fuel to forge a path to studying a dual degree in art history and religion. After years working in and around the heritage sector and religious spaces, I later pursued a graduate degree in architectural history, focusing on places of worship that have been historically used and reused by communities of different faiths and cultural backgrounds.

Adalberto Memorial United Methodist Church in Chicago’s West Town community area is an example of a storefront church.

I’ve realized the common thread of much of this work has been themes of community and belonging:

- What does it mean to create, cultivate, and preserve a shared sense of history and identity?

- How do we take something as personal and internal as belief and make it external and appearing in physical space?

- How do we create a safe space to explore these themes?

- How do we uplift the experiences of those who have been silenced or forcibly forgotten in these narratives?

For me, these questions are not something that can be answered alone. They depend on the work of a community. The word “community” implies having something in common—be that geographic lines, traditions, interests, cultural backgrounds, racial or ethnic identities, religious practices, or shared goals. This can feel like something that is simultaneously inclusive and exclusive, something that’s bounded by commonality while creating a sense of an “other.”

A mural in Chicago’s Back of the Yards neighborhood depicting the Virgin Mary, the city skyline, and two small vendor tents, one of which is selling tacos.

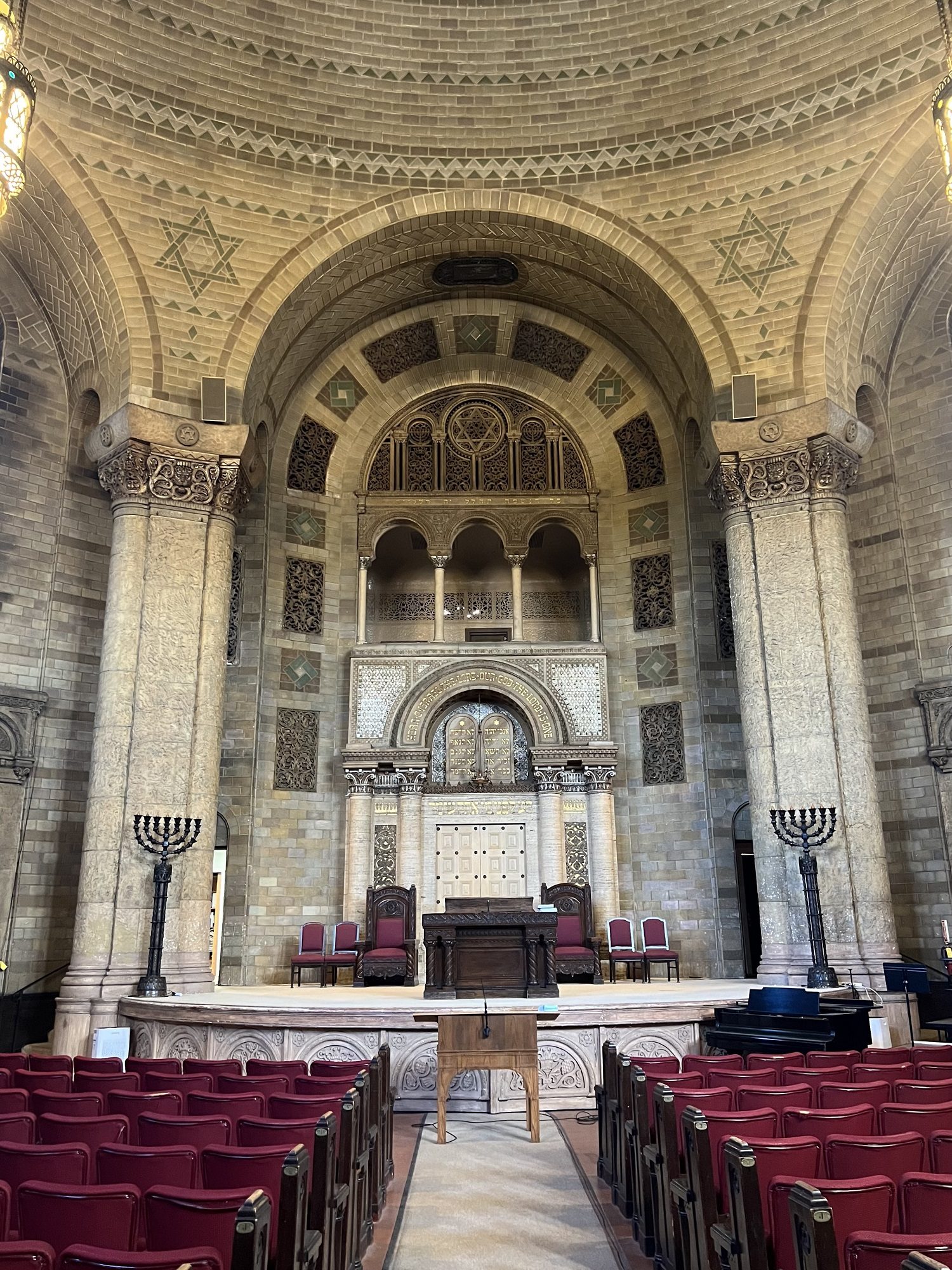

Places of worship have been a common way community is formed, making religious identity important to shaping our historic landscape. Identity is demarcated in space through coming together. This not only takes shape through built form but in finding common purpose, making community more than a boundary but also an action—to be in community. A subtle shift in language makes it something you know when you feel, see, and experience its presence or absence.

Located in Chicago’s Kenwood neighborhood, Kehilath Anshe Ma’arav (KAM) Isaiah Israel was founded in 1847 and is the oldest synagogue in Illinois.

To put this into practice, I continue to frame my work today through ideas of shared space and sense of place. As with many institutions that face legacies of being historically exclusionary, how can we confront tensions openly and honestly to create communal belonging? It takes movements. As Patel writes in Acts of Faith, “Movements recreate the world. A movement is a growing group of people who believe so deeply in a new possibility that they participate in making it a reality.” It’s my hope that, through this work together, we can create a new reality of equity, equality, justice, and truth coming together for sharing Chicago stories through the remnants and rhythms of its religious past and present.

Want to know more? Rebekah will be answering questions on Instagram during Ask a Museum on Wednesday, September 14, 2022!

For Labor Day, we’re highlighting the work of labor leader, antiwar activist, and author Sidney Lens, whose papers are archived at CHM. Ask about them on your next visit to the Abakanowicz Research Center.

Staughton Lynd, Rev. James Bevel, Sidney Lens (second from left), and Richard Flacks of the Chicago Area Draft Resisters speak at a press conference at 333 West North Ave., January 8, 1968. ST-60003475-0006, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Sidney Lens was born in 1912 in New Jersey to Charles and Sophie Okun, Russian Jewish immigrants who came to the United States in 1907. Lens’s father died when Lens was just three years old, so he was raised by his mother, who worked in a garment factory in Manhattan. Lens described his mother as an influence on his organizing and recalled her giving him a picture of Rosa Luxemburg when he was young.

Lens’s first effort at organizing workers occurred when he was just a teenager, working as a busboy at a resort in Saratoga Springs, New York. He organized the waiters and busboys to strike on July 3, but ultimately the resort was able to pull in family and friends to wait tables in their place, and Lens was taken off the resort and roughed up by the county sheriff.

Undeterred by his first attempted labor strike, Lens continued to empower and organize workers, particularly in the 1930s as New Deal legislation was being passed in response to the Great Depression. In 1937, he helped organize workers who made automobile seat covers and sheet metal workers in Detroit.

Hillman’s Pure Foods, northwest corner of Devon and Artesian Streets, 1937; Chicago Architectural Photographing Company. CHM, ICHi-061991

Making Chicago his base, Lens undertook organizing efforts among fellow workers at the Hillman’s grocery chain in 1941. He helped regroup workers whose unions were under the Capone outfit (which was stealing their dues) into the United Grocery and Produce Employees Union, Local 329 of the Retail, Wholesale, and Department Store Union (CIO). Eventually, Local 329 (known from 1946/47 as the United Service Employees Union) won an election ordered by the National Labor Relations Board.

In the next few years, Lens widened his organizing efforts on behalf of Local 329 but also to hospital workers, dancers, language teachers, and even the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. He also served as the national secretary of the American Forum for Socialist Education.

In 1946, Lens married Shirley Ruben, a Chicago public school teacher who became known in the 1950s for refusing to take an anti-Communist loyalty oath. In the early 1950s, the couple began a series of travels, which eventually took them to 101 countries. These travels broadened Lens’s perspective and furthered a keen interest in international affairs and antiwar activism.

Anti-war button owned by Sidney Lens, c. 1970. CHM, ICHi-040649

Along with David Dellinger, Bayard Rustin, Roy Finch, A. J. Muste, and Glen Gardner, Lens was one of the founding editors of the pacifist journal Liberation (1956–77). Lens was also a prolific author and wrote more than twenty books, including The Crisis of American Labor (1959) and The Forging of the American Empire (1971). He also contributed to The Progressive magazine and was a contributing editor for the National Catholic Reporter. During the 1950s, his scathing articles denouncing McCarthyism and the Cold War brought him national attention.

In Chicago, Lens was among the many to challenge the activities of the Chicago Police Department’s Red Squad, which spied on political activities of groups in the city. In 1967, he recalled receiving a phone call from officers who told him how they had burglarized organizations in the city, including Women for Peace, Chicago Peace Council, Fellowship for Reconciliation, and Students for a Democratic Society. Lens tipped off the Daily News with the information and was one, among others, who sued for dissolution of the Red Squad.

In the 1970s and ’80s, Lens labored on behalf of nuclear disarmament, founding the organization Mobilization for Survival. Lens spent more than fifty years as an activist. It was only illness that stopped him. He died on June 18, 1986, at Chicago’s Bernard Mitchell Hospital from a recurrence of a malignant melanoma.

Further Resources

This summer, Lily Mayfield assisted CHM technical services librarian Elizabeth McKinley in the Abakanowicz Research Center. Mayfield writes about her experience discovering the full names of women featured in the Museum’s carte de visite collection.

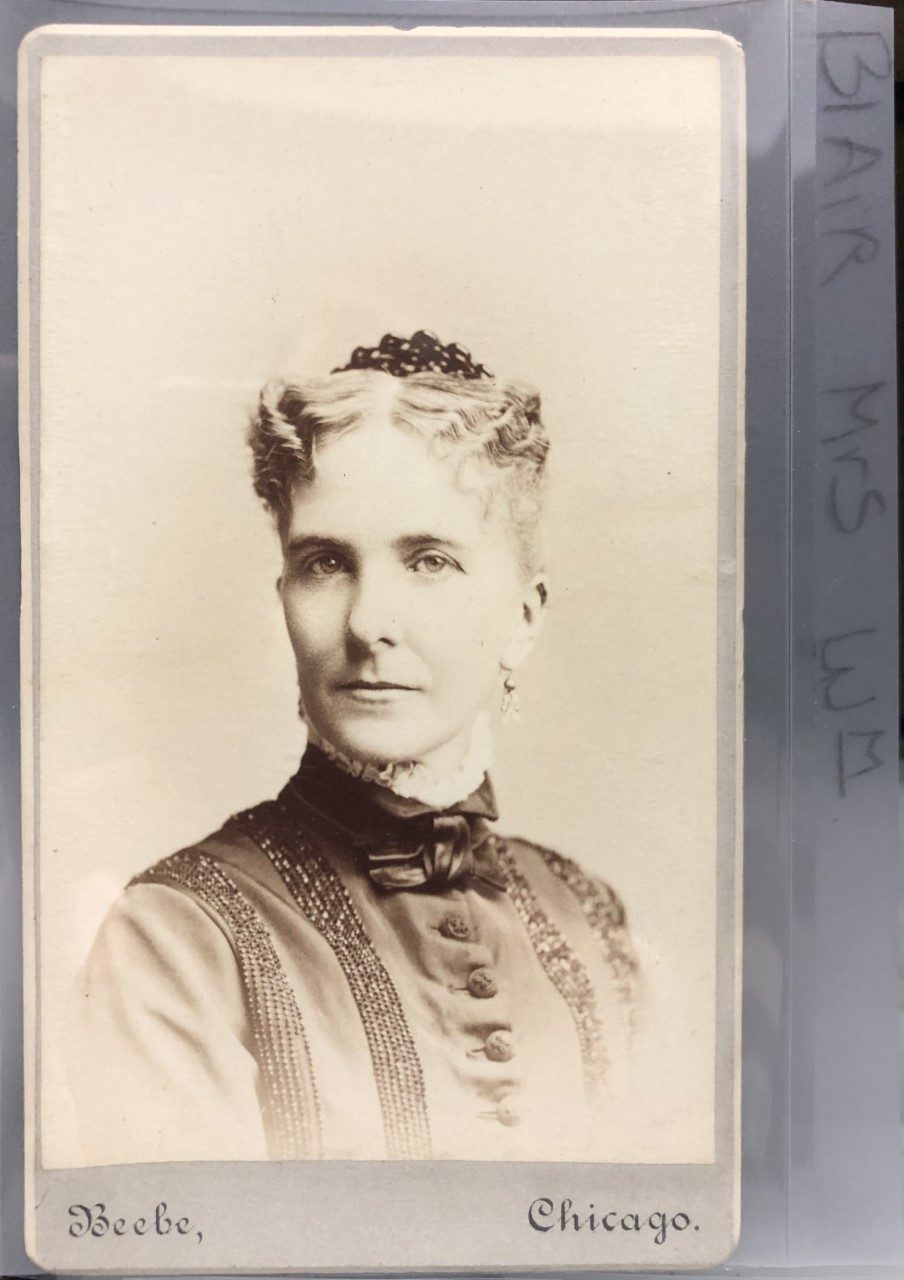

How can one study the past without knowing the names of those who came before? That is the question posed by Lily Mayfield, a practicum student from Dominican University’s Master of Library and Information Science program, who spent the summer assisting CHM technical services librarian Elizabeth McKinley in discovering the full names of women featured in the Museum’s carte de visite collection. Many of the women pictured in the cartes de visite are identified by just their husbands’ names (e.g., Blair, William, Mrs.), which can create roadblocks for researchers.

Women assuming their husbands’ names has been a widespread practice for centuries, but when women’s premarriage names are not recorded, their identities and histories are effectively erased. Moreover, there is no standard for the way wives’ names are recorded. “Blair, William, Mrs.,” “Baker, Ed, Mrs. (Mary Furbeck),” Gibson, Mrs. J. M.,” and “Brown, Mary A., Mrs.” are just some examples we encountered.

Carte de visite of Mrs. William Blair (see bib# 31434). Thanks to Mayfield’s research, the catalog record for this photograph is now updated with a heading that reflects Mrs. Blair’s full name, “Blair, Sarah Maria Seymour, 1832–1923.”

How does one recover a name that has been lost to history? In the case of the carte de visite collection, we found several premarriage names handwritten on the front or back of photographs. However, this was not the norm, and, in most instances, further research was required. We referenced photographs of headstones (via Findagrave.com), census records (via HeritageQuest), wedding announcements, and obituaries (via ProQuest‘s historical Chicago Tribune). Google and Wikipedia searches led to useful information as well.

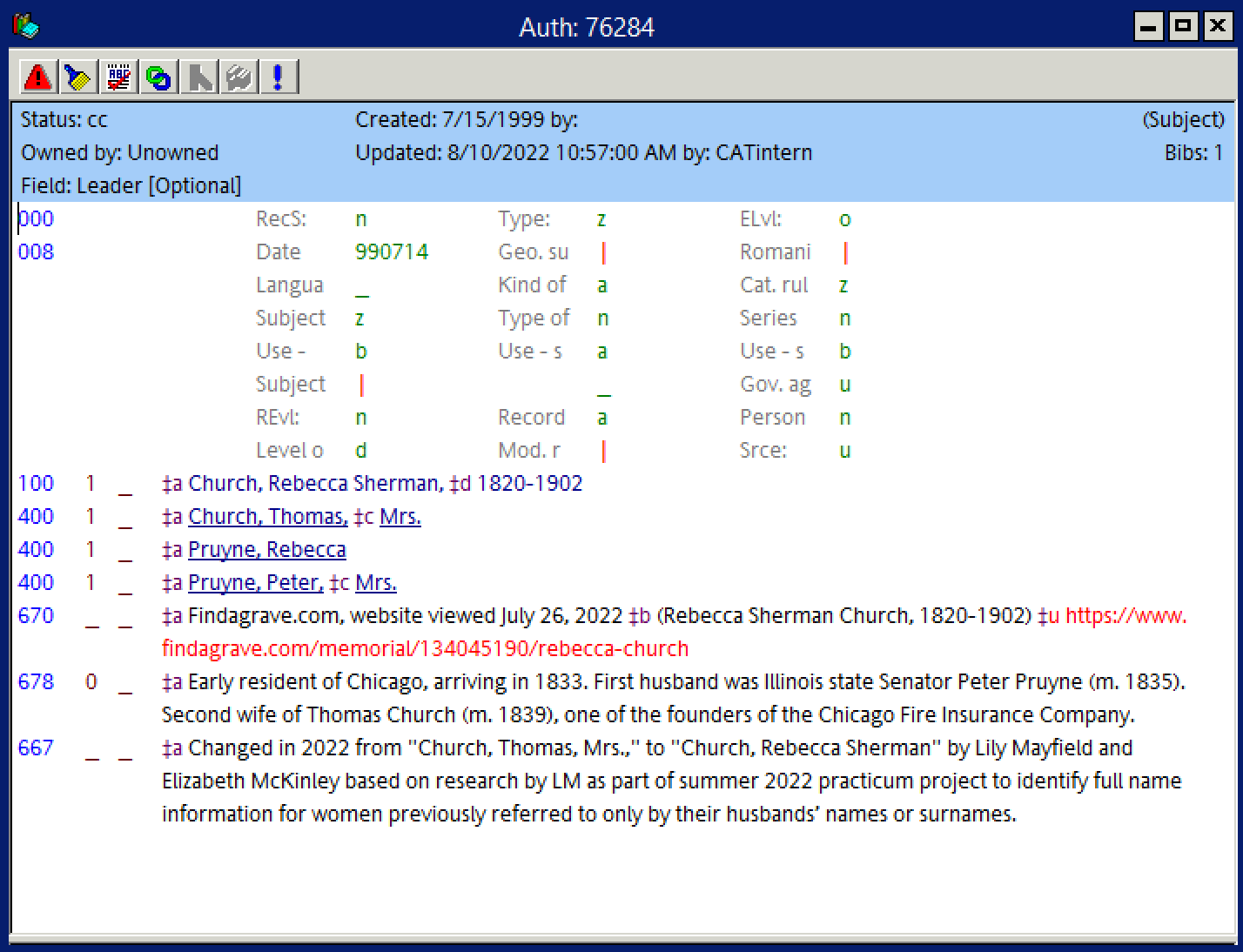

After confirming the full names, we updated the authority records in CHM’s integrated library system, Horizon (accessible to the public via ARCHIE). The most significant update involved changing the original heading (e.g., Church, Thomas, Mrs.) to the variant form, and making the recovered full name (e.g., Church, Rebecca Sherman, 1820–1902) the main heading.

The updated authority record for “Church, Rebecca Sherman, 1820–1902″

In addition to the authority records, sometimes we made changes to the bibliographic records. Any handwritten notes on the front or back of the photos were transcribed and added to the record. If we discovered important biographical or historical information during the research process, we added it in a public note. We also checked the title and physical description to ensure the record matched the physical item.

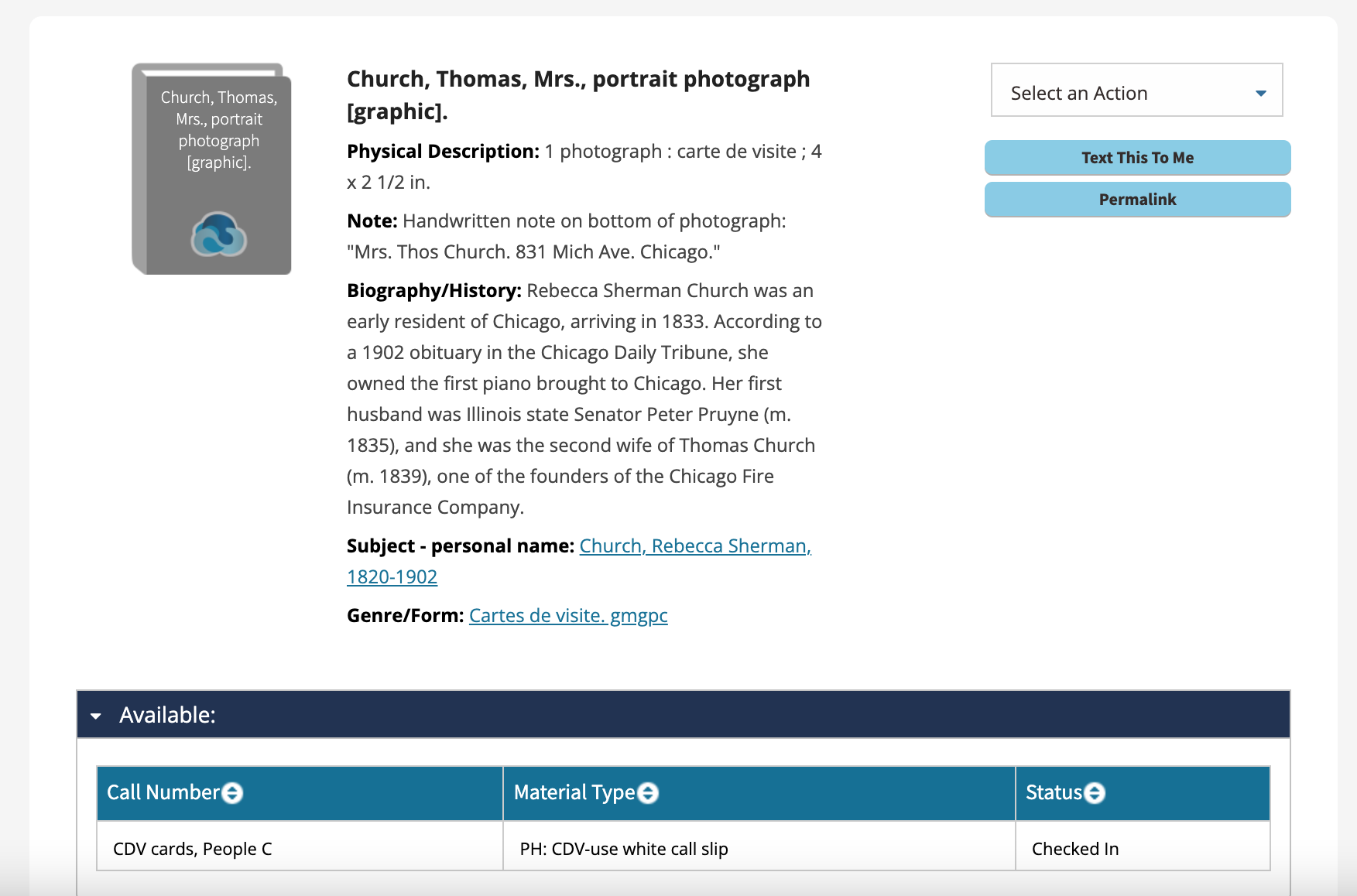

Carte de visite of Mrs. Thomas Church (see bib# 31924). Thanks to Mayfield’s research, the catalog record for this photograph is now updated with a transcription of the handwritten note, a heading that reflects Mrs. Church’s full name (“Church, Rebecca Sherman, 1820–1902”), and additional biographical information.

Updated bibliographic record in ARCHIE.

The issues stemming from the lack of women’s premarriage names were made even more complicated if a man married multiple times and had sons who were named after him. One such situation occurred when attempting to disambiguate Mrs. Marshall Field. More than one catalog record cited a “Mrs. Marshall Field,” but without a first name, maiden name, or birth and death dates, it was impossible to know whether the records referred to the first or second wife of Marshall Field. After comparing the photographs in the collection with digitized photographs and portraits found online, we were able to correctly identify the women. With the names now clearly recorded (“Nannie Douglas Scott Field, 1840–1896″ and “Delia Macomber Spencer Field, 1853–1937″), future researchers will be able to avoid the same confusion.

[L] Mrs. Nannie Douglas Scott Field, the first wife of Marshall Field I. [R] Mrs. Delia Macomber Spencer Field, the second wife of Marshall Field I. In examining the photographs, we also discovered these cabinet cards had been incorrectly recorded as cartes de visite. We updated the catalog records to reflect this.

This project addressed only a small portion of one photograph collection. CHM’s Research and Access department intends to continue this work and provide full names, where possible, for women featured in all CHM collections. It is an ongoing process that will take time, and we intend to keep researchers informed of our progress. We welcome any questions or comments at research@chicagohistory.org.

Additional Resources

August 18 is National Mail Order Catalog Day. This year, the Chicago History Museum is celebrating the 150th anniversary of the company responsible for that designation: Montgomery Ward.

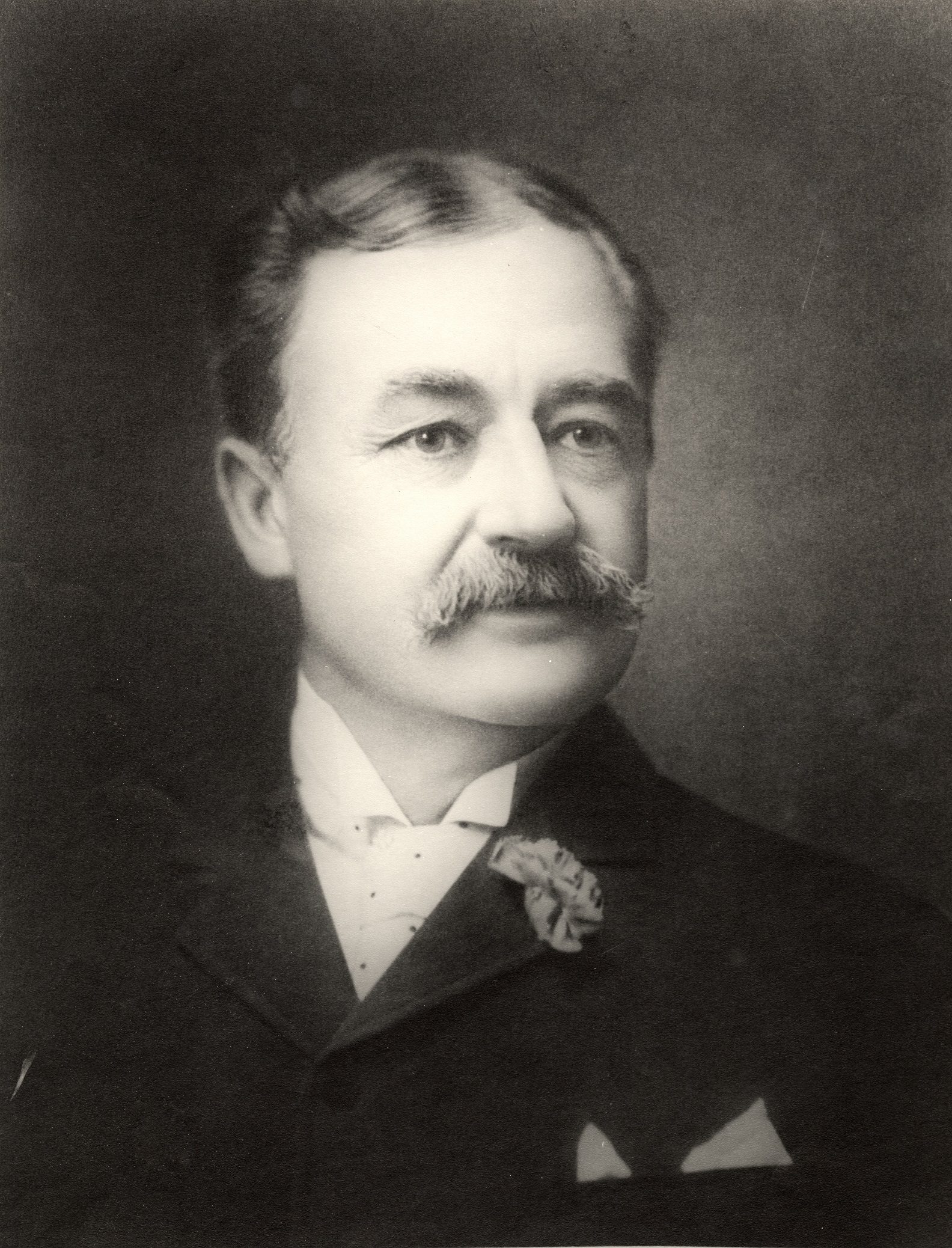

Portrait of Aaron Montgomery Ward. CHM, ICHi-062410

The well-known company was founded by Aaron Montgomery Ward in 1872, with a mission to make its products more available to the public, especially consumers in rural and farming communities. Ward issued its first mail order catalog on August 18, 1872. It was printed on a single sheet of paper, offering 163 distinct items. What made Ward’s catalog the first of its type was its accessibility. It was the first extensive mail order catalog for the masses. Comparatively, other mail order services up to this point were either industry/trade specific or for an elite customer base.

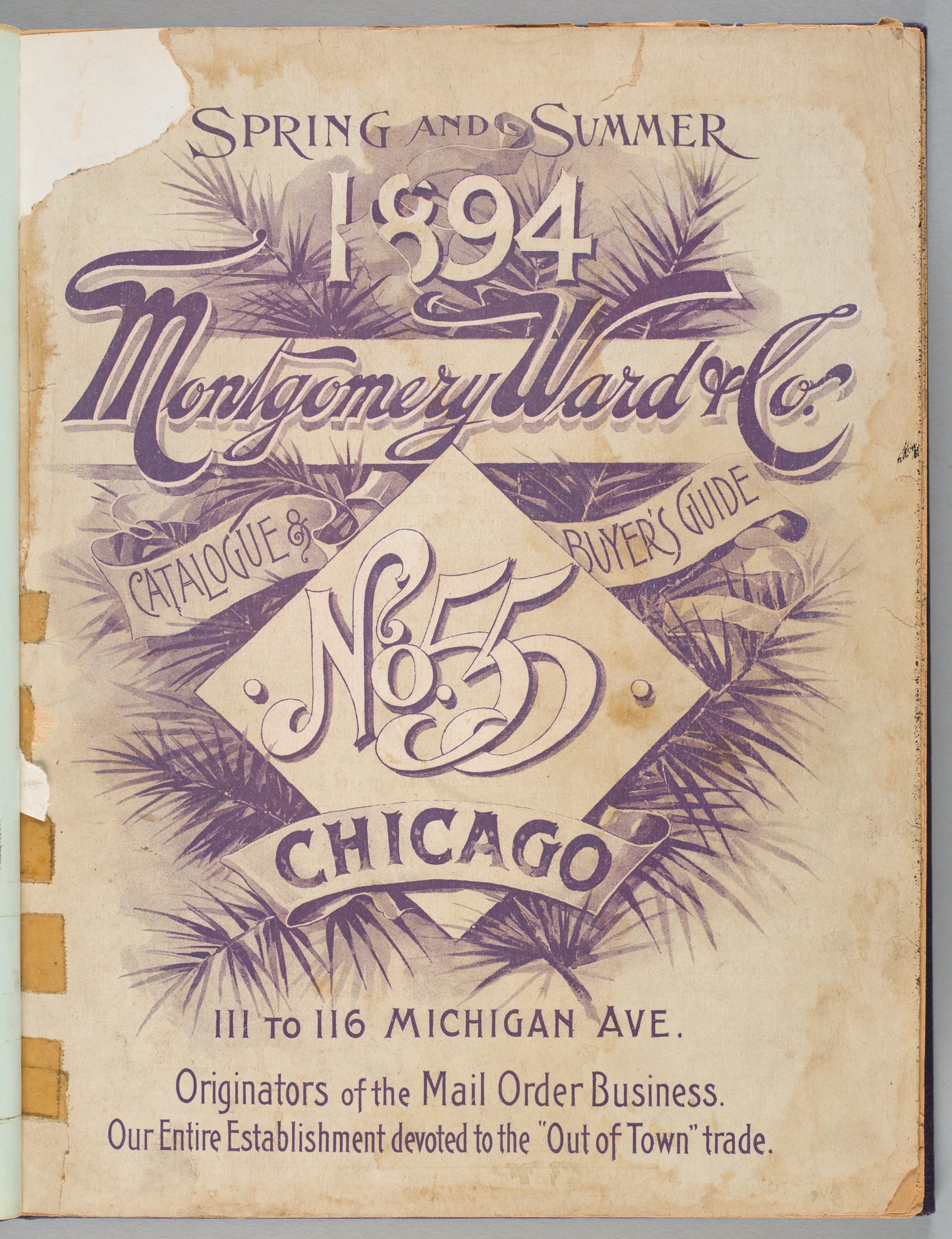

Front cover of the Montgomery Ward & Company catalog and buyers guide No. 55, Spring and Summer 1894, Chicago. CHM, ICHi-092917

Ward’s catalog would quickly prove to be a success, with the catalog growing to 32 pages by 1874 and to 152, with 3,000 items, in 1876. Its offerings were popular with Americans at every economic level and were backed by the company slogan, “satisfaction guaranteed or your money back,” an industry first. By the beginning of the 20th century, Ward’s catalog had more than 3 million subscribers to its mailing list. Customers were able to order everything on the catalog from clothing and farming equipment to entire homes.

Advertisement broadside of Montgomery Ward & Co. located at Michigan Avenue and Madison and Washington Streets, 1899, Chicago. CHM, ICHi-001622

To satisfy the ever-growing needs of the business operation, Ward built an enormous campus on the north branch of the Chicago River at 618 W. Chicago Avenue comprising an eight-story building, a storefront, and executive offices. Construction on the “mail order house” complex began in 1907, with an estimated cost of $2.5 million (approximately $75 million today). Upon its completion, it was declared one of the largest man-made structures in the world, with its miles of chutes, conveyor paths, and hallways. The building even had a dedicated building courier system, which relied on roller-skating routes across the building for delivering interdepartmental packages and communications. The building still stands today and is a city landmark that has been redeveloped into a mixed-use complex with residences, eateries, and corporate offices for several companies.

Exterior view of the Montgomery Ward complex, located at 618 W. Chicago Avenue, Chicago, c. 1960. CHM, ICHi-173785

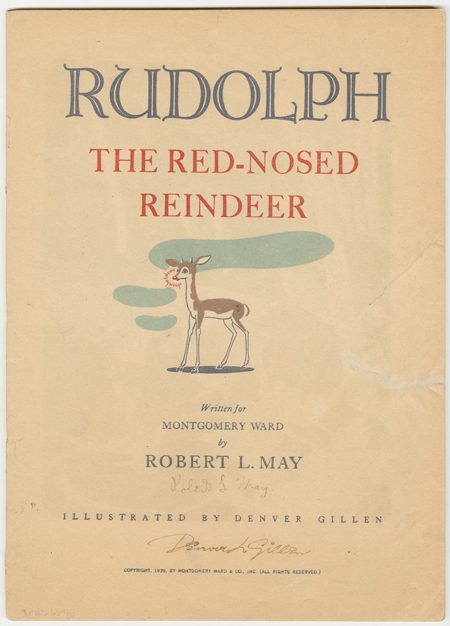

Beyond their success in the mail order industry, as many Chicagoans surely remember, Ward expanded into the retail sector in 1926 with the opening of its flagship store in Chicago, located on S. Michigan Avenue. By the start of the 1930s, Ward operated more than 500 stores in the United States, and it was the largest retailer in the country. Most Americans are familiar with perhaps the most notable creation to come from Montgomery Ward in the 1939 holiday season, with company copywriter Robert May’s creation of a certain red-nosed reindeer named Rudolph.

Cover of an original Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer written for Montgomery Ward & Co. by Robert L. May and illustrated by Denver Gillen, 1939. CHM, ICHi-068483

In the latter half of the 20th century, Ward went through several ownership changes that had a drastic impact on company operations. It issued its final mail-order catalog in 1985, and just over a decade later in 1997 it would file for bankruptcy, closing all its remaining brick-and-mortar stores shortly thereafter. Today, the company remains active primarily in e-commerce, with its rights having been acquired by a holding company.

Further Reading:

In recognition of International Workers’ Day, we’re spotlighting the Teamsters Union and its history in Chicago.

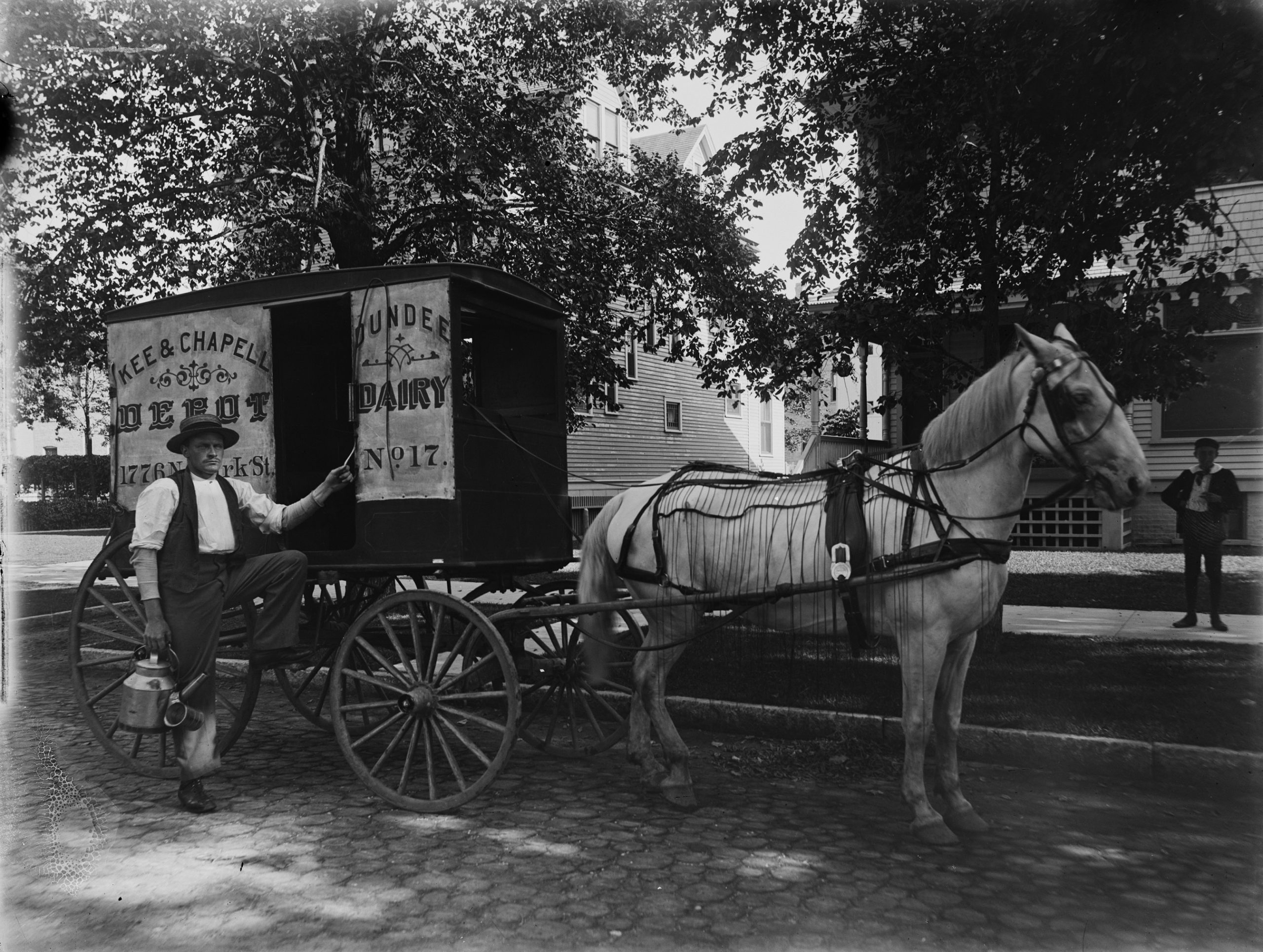

Historically, the term “teamsters” referred to commercial road transportation workers. Before 1945, most teamsters worked locally, driving “teams” of horses throughout Chicago. By the late twentieth century, national road networks enabled an interstate trucking industry, which employed many long-haul drivers and expanded the meaning of the term.

Local processors had to rely on various forms of transportation to bring milk from farms and to distribute it to its consumers. Kee & Chapell Depot/Dundee Dairy horse-pulled cart, Chicago, c. 1895, The business was located at 1776 N. Clark Street. CHM, ICHi-072655

In the late 1860s, Chicago hack owners and drivers organized to stabilize hack fares. Around the turn of the century, teamsters began to organize labor unions. With help from the American Federation of Labor, the Team Drivers International Union (TDIU) was formed in 1898 with its headquarters based in Detroit. A few years later, a Chicago group broke from the TDIU and formed the Teamsters National Union. The Chicago-based union did not allow large employers to become members and advocated more aggressively than the TDIU for higher wages and shorter hours. Ultimately, the two unions merged in 1903 to form the International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT), also known as the Teamsters Union, and they elected Cornelius P. Shea as their first president.

Informal portrait of Cornelius P. Shea, Teamsters president, sitting between Emmett T. Flood (left) and John F. Eyrrell (right) in a room with police officers in Chicago, c. 1922. DN-0074556, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

By 1905 the IBT had established a joint council in Chicago, with forty-five affiliates and 30,825 members. These locals were militant, assisting other unions in their struggles for recognition. In 1905, teamsters aided striking employees of Montgomery Ward & Co. When other businesses and the Employers’ Association of Chicago rallied to Ward’s defense, the dispute spread quickly. Riots broke out almost daily, and the 103-day conflict led to twenty-one deaths. After the employers’ victory, some locals deserted the IBT, forming a rival Chicago Teamsters’ Union (CTU).

Injunction notice on a Montgomery Ward truck at time of the Teamsters strike, Chicago, 1905. CHM, ICHi-071886; Charles R. Clark, photographer

Testimony after the strike revealed that some union leaders had taken bribes to end the strike, which weakened public support for unions. In the 1920s and ’30s, union leadership continued to face accusations of corruption, coercion, and gangsterism from businessmen, while radical labor organizers like William Z. Foster charged them with selfishly thwarting mass unionism. Such accusations continued into the following decades—and weren’t all without merit. In 1929, the Teamsters and other unions in Chicago approached gangster Roger Touhy for protection from Al Capone and his Chicago Outfit, which were seeking to control the area’s unions.

Roger Touhy around the time of his criminal trial, Chicago, 1934. DN-A-5250, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

The Teamsters survived these allegations and remained influential in Chicago labor circles. After reincorporating the CTU locals in 1937, the IBT expanded by organizing transportation, clerical, retail, and manufacturing workers. William A. Lee of the bakery drivers local served as Chicago Federation of Labor president from 1946 to 1984.

WCFL was the nation’s first and longest-surviving labor radio station, created in 1926 by the Chicago Federation of Labor, Chicago. CHM, ICHi-073048; Burke & Dean, photographer

However, the AFL-CIO (American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations) expelled the IBT in 1957 in large part due to corruption charges against Dave Beck, Teamsters president from 1952 to 1957, and Jimmy Hoffa, who served as president from 1957 to 1971. Although Hoffa helped unify the Teamsters in 1964 under the National Master Freight Agreement—a milestone national agreement for teamsters’ rates, which covered more than 450,000 truck drivers—and helped expand the union’s growth, he faced major criminal investigations. He was convicted of jury tampering, attempted bribery, conspiracy, and mail and wire fraud in two separate trials in 1964, one in Nashville and one in Chicago.

Union boss Jimmy Hoffa meets with lawyers during his trial at the old Federal Courthouse, Chicago. ST-17500700-E1, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM; Gene Pesek photographer

When Hoffa entered prison in 1967, Frank Fitzsimmons was named acting president. He continued on as president after Hoffa resigned in 1971. Under Fitzsimmons, Teamsters authority was decentralized back into regional and local leaders. Today, the Teamsters remain one of the largest labor unions in the world with 1.2 million members, with members ranging from brewers and bakery workers to airline pilots and sanitation workers.

Additional Resources

- Listen to Studs Terkel’s 1991 interview with labor activist and historian Dan La Botz, author of Rank-and-File Rebellion: Teamsters for a Democratic Union

- For more on the history of labor unions, visit our exhibition Facing Freedom in America or its companion website

- See the “Teamsters” entry in the Encyclopedia of Chicago

The National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) awarded the University of Chicago Library, in partnership with the Chicago History Museum and Newberry Library, a grant to digitize historical maps of Chicago through 1940. The grant of $348,930 will fund the proposal “Mapping Chicagoland” and support the enrichment of the digital images with geographic information for use in spatial overlays and analyses, as well as the work to make them open to the public on the UChicago Library website. The maps will also be available through the BTAA (Big Ten Academic Alliance) Geoportal and Chicago Collections Consortium platforms.

The collaboration will draw on materials from all three institutions and leverage expertise and resources at the UChicago Library to scan, add spatial data, create metadata, and make openly available 4,101 digitized maps in Fall 2024. The maps range from the earliest cartographic representations of Chicago prior to its incorporation through its rapid expansion in the early 20th century. Maps from that period are rich sources of information for scholarly and community study that illuminate the history and contribute to our understanding of contemporary Chicago.

Leading the project is Cecilia Smith, Director of Digital Scholarship at UChicago Library, in collaboration with James Akerman, Director of the Newberry Library’s Smith Center for the History of Cartography, and Ellen Keith, Director of Research and Access and Chief Librarian at the Chicago History Museum.

“The importance of these maps to our understanding of Chicago’s development is foundational,” said Smith. “Bringing our collections together in one openly accessible, digital place will have international impact for scholars and students. I am thrilled by the Endowment’s support of our collaboration, and I look forward to working with our partners to engage the Library’s deep digital expertise.” Ellen Keith said, “We were excited when Cecilia Smith proposed this collaboration and grateful to NEH for funding this project. The Chicago History Museum’s map collection complements those of the University of Chicago and the Newberry Library.” Together, these institutions will create a valuable resource for scholars and map enthusiasts alike. Each institution’s collection of Chicago maps has unique strengths that complement one another in scale, time period and subject.

The Chicago History Museum map collection includes maps of the area as early as 1812 and maps from Rufus Blanchard, one of the city’s first map publishers. Maps are categorized by topic, such as annexations and accretions, communities, parks, wards, industries, transportation, topography, cemeteries, world’s fairs, and population. “We are excited to see how this project as a whole will expand the use of these primary sources and preserve a rich body of information on Chicago’s dynamic and complex urban development,” said the Chicago History Museum’s President Donald Lassere.

The University of Chicago’s maps range from 1853 to 1940 and include maps produced by its Social Science Research Committee and map publishing companies, such as Rand McNally, transportation and utility companies and civic institutions. The maps cover social, urban, and economic features such as land use, parks, and urban planning. Adrienne Brown, Associate Professor in the Department of English at UChicago, emphasizes the value of digitizing the collection for researchers: “Having thought a lot about how topography of Chicago has been illustrated, analyzed, and made anew through processes of mapping in my own research on the history of architecture, real estate, race, and aesthetics, I can unequivocally say that having digital access to these materials will not only improve my future scholarship but will expand and deepen the work of countless scholars to come.”

The Newberry selected its extensive collection of large-scale real estate, fire insurance, and land valuation atlases of parts of Chicago published from 1872 to 1924 for inclusion in this project. Among these are two atlases detailing the grounds of the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 and the Union Stock Yard. The atlases show footprints of individual structures and lots, providing large scale details for studying Chicago’s cultural geography. “Collaborative digitization projects like ‘Mapping Chicagoland’ offer an ideal way of enhancing and multiplying access to our collection,” said Daniel Greene, President and Librarian of the Newberry Library. “This project is an especially appropriate partnership because it taps into our great collecting strengths in historical cartography and Chicago history.”

These early maps and atlases of Chicago are among the most popular collections within the three Institutions, but only a small fraction of these maps is currently available digitally. Providing open access to digitized and georeferenced map images will allow scholars worldwide to pursue broad research goals and incorporate primary and secondary cartographic sources in their teaching of Chicago’s pivotal transition into the 20th century.

“The University of Chicago Library is deeply involved in two organizations focused on documenting the history and culture of Chicago: The Black Metropolis Research Consortium (BMRC) and the Chicago Collections Consortium (CCC). Having such a rich geographical data source about the city will provide new dimensions to the kind of research that students and scholars can do with these consortia collections,” said Elisabeth Long, Interim Library Director. “For example, the BMRC Summer Fellows program has hosted many scholars whose research looks at spatial aspects of Black history in Chicago–redlining, food deserts, health services and activism to name a few—which would benefit from having geo–referenced historical maps of the city. I am pleased that we can leverage the Library’s digital expertise to develop this important collaborative resource.” The Chicago History Museum is a member of both The Black Metropolis Research Consortium and the Chicago Collections Consortium.

The NEH grant is part of the Humanities Collections and Reference Resources (HCRR) program, which advances scholarship, education, and public programming in the humanities by helping organizations steward important collections. Of the 206 eligible HCRR applicants received by the Endowment this round, 36 proposals were selected. In the funding announcement, the NEH chair Shelly C. Lowe said that the “projects will expand the horizons of our knowledge of culture and history, lift up humanities organizations working to preserve and tell the stories of local and global communities, and bring high-quality public programs and educational resources directly to the American public.”

In the run-up to the opening of our newest exhibition, Treasured Ten: Selections from the Costume Collection, we’re spotlighting one of its co-curators, Jessica Pushor, as she gives some insight into her job and how the garments were selected.

Jessica in costume storage during Members’ Open House, June 2014. All photographs by CHM staff

“If you can wear it, I take care of it.”

The pithy statement sums up the work of Jessica Pushor, the costume collection manager at the Chicago History Museum. With more than 50,000 pieces in her care—including garments, accessories, jewelry, sportswear, and more—her day-to-day work can include cataloging and inventorying the collection, creating mounts for objects going on display, leading tours, or working with scholars and researchers.

Jessica points out garment details to CHM members, June 2014.

The Museum’s world-renowned costume and textiles collection dates from the eighteenth century to the present and is noted for its size, quality, and range of holdings. Costume materials include work by distinguished designers, such as Charles Frederick Worth, Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel, Charles James, Christian Dior, Yves Saint Laurent, Halston, Gianni Versace, and Christian Lacroix, and many dressmakers, milliners, retailers, and manufacturers who made Chicago their home. The collection includes clothing worn by former presidents and first ladies, sports stars, celebrities, and other notable individuals, as well as by everyday Chicagoans. Together, these materials—both exceptional and commonplace—reflect the history of Chicago as an evolving urban center and document fashion history through the lens of the city and its people.

Jessica buttons up a Willi Smith jacket during photography for Treasured Ten, November 2021.

When the opportunity arose for the Museum to experiment with a small-format costume exhibition, Jessica wanted to make the most of it. This new opportunity was a chance to showcase previously unseen treasures from CHM’s massive costume collection and be more inclusive in the Chicago stories we tell. Along with co-curator Charles E. Bethea, the Andrew W. Mellon Director of Collections and Curatorial Affairs at CHM, she selected ten garments—two each by five designers. Opening April 9, 2022, Treasured Ten: Selections from the Costume Collection looks at the lives and work of local luminaries Barbara Bates and Scotty Piper and international icons Stephen Burrows, Willi Smith, and Patrick Kelly.

Jessica adjusts the cowl of a Stephen Burrows garment, November 2021.

Want to hear more from Jessica? She and Charles will be presenting at the members’ preview of Treasured Ten: Selections from the Costume Collection on Friday, April 8!

Treasured Ten: Selections from the Costume Collection is sponsored by the Costume Council of the Chicago History Museum.

Treasured Ten: Selections from the Costume Collection is sponsored by the Costume Council of the Chicago History Museum.

Additional Resources

- Read Jessica’s blog posts

- Follow Jessica on Instagram @jessica_pushor

- Listen to Jessica talk about CHM’s costume collection on the podcast Dressed: The History of Fashion: Part 1, Part 2