Latest Posts

The Vietnam War Veterans Recognition Act was signed into law in 2017, making each March 29 a day to honor and commemorate Vietnam War veterans. More than 9 million American personnel served on active duty from 1964 to 1975.

Exterior view of Our Lady of Guadalupe, Chicago, November 19, 1999. CHM, ICHi-039078

One Chicago institution with deep ties to the ongoing legacy of the Vietnam War is Our Lady of Guadalupe Church in South Chicago at 91st Street and Brandon Avenue.

Our Lady of Guadalupe began serving the predominantly Mexican families on Chicago’s Southeast Side in 1923, holding services in a former military barrack. The Mexican community developed around the city’s shipyards and steel mills, where they found steady and nearby jobs as they settled in the area. In fact, the church was an important sign that a population of once-migrant workers had coalesced into a community. In 1924, the Claretian Missionaries took over Our Lady of Guadalupe and constructed the current church edifice, a project to which parishioners in the community contributed significantly. The completion of the church marked it with the distinction of being the first house of worship in the city to offer services for Spanish-speaking people, though their early masses were in Latin. Under Claretian leadership, the church would also become home to the National Shrine of St. Jude, patron saint of hope and impossible causes.

Exterior view of the entrance to Our Lady of Guadalupe Church, Chicago, November 19, 1999. CHM, ICHi-039829

By the 1960s, at the height of the Vietnam War, South Chicago was a bustling community with Our Lady of Guadalupe at the heart of social life. Many in the community felt a call to action to serve in the armed forces as the conflict abroad continued to grow, even as antiwar protests continued to mount across the nation. For many of the Mexican men from the neighborhood who enlisted or had their number called in the draft, military service was already a part of the family history, as several older community members were veterans of World War II and the Korean War. This patriotism would come at a high cost, not just for these men’s families, but for the South Chicago community as a whole.

Vietnam veterans’ memorial at Our Lady of Guadalupe Church, Chicago, November 19, 1999. CHM, ICHi-039828

Our Lady of Guadalupe is believed to be the parish with the largest loss of life in the war not just in the city, but across the entire United States. The parish community lost twelve men: Edward Cervantez, Antonio G. Chavez, Leopoldo A. Lopez Jr., Joseph A. Lozano, Michael S. Miranda, Raymond Ordoñez, Thomas R. Padilla, Joseph A. Quiroz, Dennis J. Rodriguez, Peter Rodriguez, and brothers Alfred Urdiales Jr. and Charles Urdiales Jr. Many who did return home from the war were also irreparably changed, suffering from PTSD and the shame associated with being a part of a highly unpopular militarized effort.

The mural as seen on Google Maps, October 2022.

For many, Our Lady of Guadalupe has become a place of memory and a place of healing. The men who lost their lives are forever enshrined in a memorial across the street from the church, dedicated in 1970, which includes a red stone depicting the names of the fallen. A mural honoring the soldiers was completed in 1990. Every year, the church becomes a pilgrimage site during Veterans Day and Memorial Day, when hundreds of visitors come to pay respect to those who paid the ultimate sacrifice in the name of serving their country. In 2002, an honorary Chicago street sign was installed at 91st Street and Brandon Avenue, naming it “Fallen Soldiers Corner.”

Additional Resources

- Listen to Studs Terkel’s interviews with many of the key figures who shaped the debate about the Vietnam War.

- View images in our collection related to the Vietnam War.

CHM curator of religion and community history Rebekah Coffman talks about the significance of Ramadan and shares a brief history of Chicago’s Muslim communities.

Sundown on March 23 marks the beginning of the Islamic month of Ramadan, a time of prayer, fasting, and personal and community reflection. Ramadan is the ninth month of the Hijri (the Islamic lunar calendar) and considered the holiest month of the year. It commemorates the revelation of the Quran to the Prophet Muhammad. Sawm (fasting) is one of the five pillars of Islam. During Ramadan, people fast from sunrise to sunset for 30 days, breaking the fast daily with the evening iftar meal. The month closes with Eid al-Fitr, a daylong celebration that includes saying special prayers, charitable giving of time and money, spending time with family, and eating delicious food, especially sweets like dates, cookies, donuts, and pies.

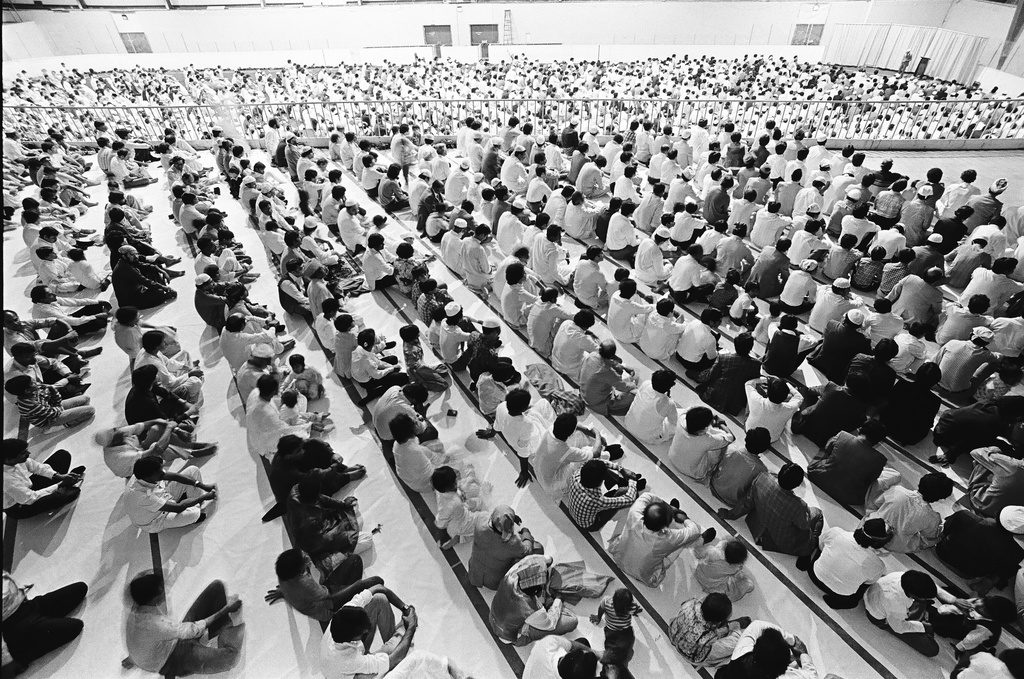

Eid al-Fitr celebration marking the end of Ramadan at the Odeum Expo Center in Villa Park, Illinois, 1983. ST-19041602-0011, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

The Muslim community in Chicago and its metropolitan area is richly diverse thanks to 130 years of migration. The first documented mentions of Islam in Chicago are from the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition (WCE), though Muslim presence in the United States predates the exposition through the lives of enslaved Africans and Middle Eastern and South Asian merchants and sailors in the 18th and 19th centuries. At the fair, Muslim migrants from Algeria, Egypt, Nubia, Persia, Sudan, Tunisia, Turkey, and India came to visit and work, with some staying and settling in the city.

Exterior and interior views of the Turkish mosque at the World’s Columbian Exposition, 1893. CHM, ICHi-020531 (left) and ICHi-093978 (right).

The WCE hosted some of the earliest purpose-built mosques in the country, with three total—one each in the Ottoman, Egyptian, and Javanese villages on the Midway Plaisance. Though the WCE officially opened after the month of Ramadan, there is documented awareness of the month of fasting. The WCE mosques hosted other religious rituals, including regular public calls for prayer, known as the adhan, and were closed to spectators during prayer times. As with most buildings constructed for the WCE, the mosques were only temporary and no longer stand today.

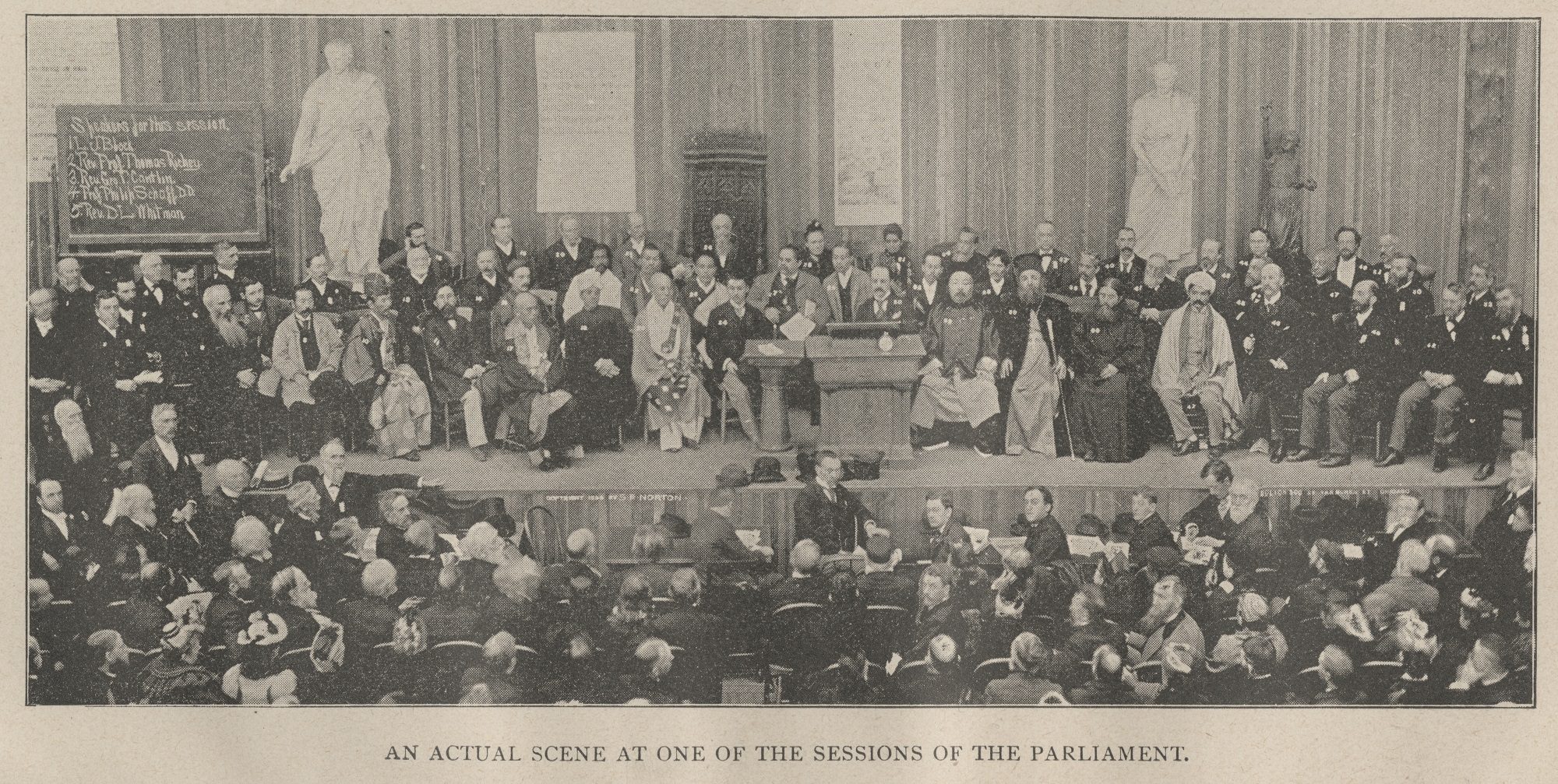

Parliament of the World’s Religions, 1893. CHM, ICHi-062640

Further awareness of Islam came at the WCE’s ancillary interfaith gathering, the Parliament of the World’s Religions. Mohammed Alexander Russell Webb, a Euro-American convert to Islam and founder of the Islamic Propaganda Movement, represented the Muslim perspective during the 16-day gathering.

Built in 1922, Al-Sadiq Mosque is one of the earliest purpose-built ones in the country and is home to the historic Ahmadiyya community, Chicago. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman

The 20th century saw major growth and expansion of Chicago’s Muslim communities. In the early 1900s, one of the country’s oldest Muslim organizations was established by the Chicago Bosniak community, the Muslimansko Podpomagajuce Drustvo Dzemijetul Hajrije (Muslim Mutual Aid Association and Benevolent Society). The 1920s saw the founding of Chicago’s Ahmadiyya community through the missionary efforts of Mufti Muhammad Sadiq from India and the establishment of the first Ahmadi Mosque. The Nation of Islam, founded by Wallace Fard Muhammad in Detroit, found home in Chicago in the 1930s through the leadership of Elijah Muhammad. The years following World War II saw an influx of immigrants and refugees from the Middle East and South Asia, yet again growing and shifting community presence.

Mosque Maryam in Chicago is an example of a former Greek Orthodox Church that was repurposed as a mosque by the Nation of Islam. CHM, ICHi-175829. Photograph by Timothy Paton Jr.

As communities formed around the city, places of gathering became essential. Mosques and Islamic centers were organized, many in adapted buildings such as homes, storefronts, and former churches or synagogues. Communities constructed buildings to house daily prayers, weekly Jum’ah (Friday prayer service), schools, and other community services. The need for more space shifted buildings from Chicago to the suburbs. Today, there are about 100 mosques in the Chicago metro area with more now in the suburbs than within city limits.

The Islamic Education Center in Glendale Heights, Illinois, is an example of a purpose-built mosque in the western suburbs. The community holds interfaith iftar dinners during Ramadan. CHM, ICHi-175837. Photograph by Timothy Paton Jr.

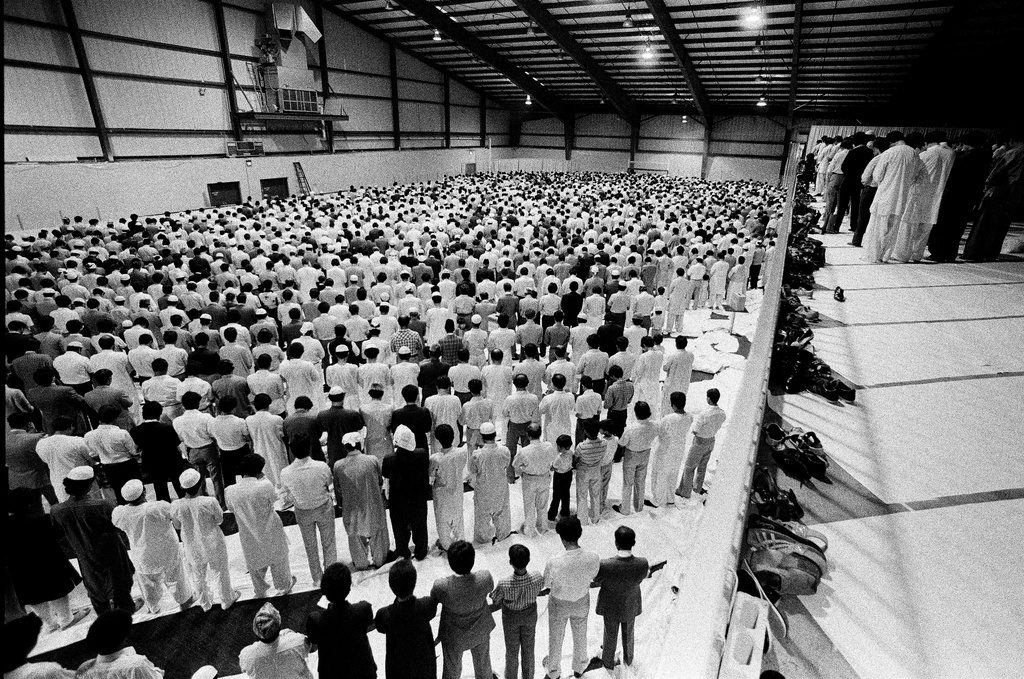

While many community activities take place within the walls of mosques or education centers, for the end of Ramadan, communities sometimes host Eid celebrations in large, outdoor spaces or in rented auditoriums or stadiums. These Chicago Sun-Times images are from such a community gathering hosted by the Islamic Foundation at the Odeum Expo Center in Villa Park in 1983.

Exterior view of the Odeum Expo Center in Villa Park, Illinois, 1983. ST-19041602-0012, Chicago Sun-Times Collection, CHM

Communal prayer during Eid al-Fitr, hosted by the Islamic Foundation at the Odeum Expo Center. ST-19041602-0074, Chicago Sun-Times Collection, CHM

The Islamic Foundation (IF) was established in 1974 by local families under the direction of community leaders including Abdul Hameed Doger and Dr. Zia Hassan to serve the Muslim community of Chicago’s western suburbs. IF began meeting in rented facilities in 1975. By the 1980s, its membership had grown to 200 families, and IF purchased the former Madison Elementary School building in Villa Park. The Eid gathering in these images took place during this transitional period, and thousands of people came to the rented auditorium to celebrate together. The community later started a full-time Islamic school in 1988. By the 1990s, the foundation had more than 2,000 members and a large expansion project took place. Today, the IF is one of the largest Islamic centers in the country and includes the IF Masjid, a library, community center, banquet hall, meeting rooms, as well as an expanded IF School. Dr. Shakeela Hassan, local community leader and widow to Dr. Zia Hassan, describes Ramadan as a time when generosity and charitable giving are at their peak, providing the opportunity to do good in the community—a spirit reflected through the Islamic Foundation’s history.

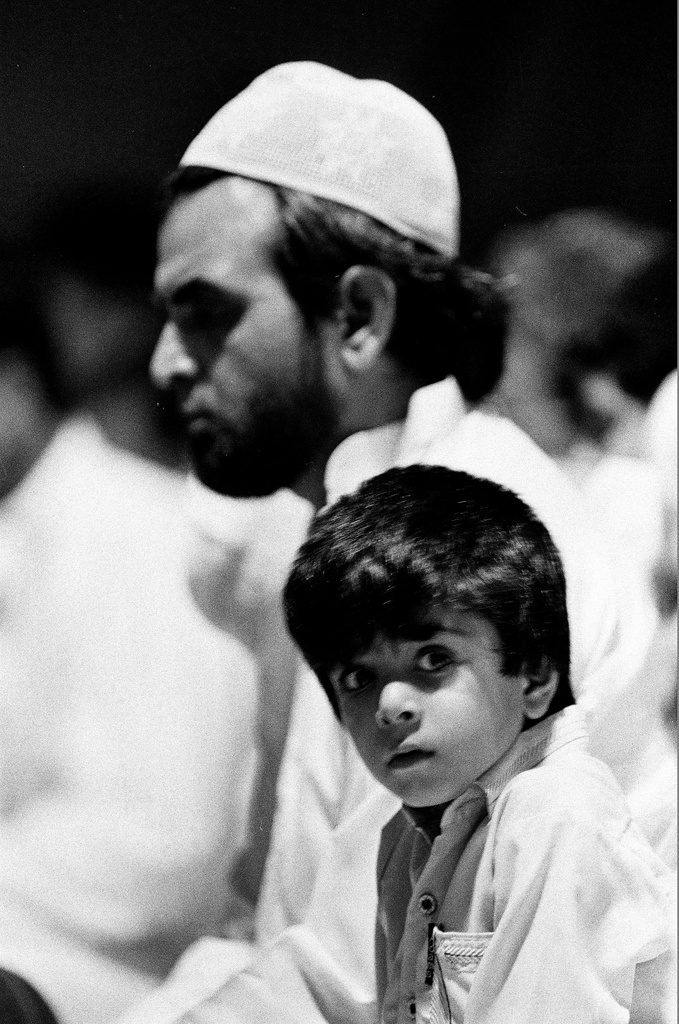

Above and below: Attendees at Eid al-Fitr at the Odeum Expo Center. ST-19041602-0015 and ST-19041602-0042, Chicago Sun-Times Collection, CHM

Additional Resources

- See more images of the Eid al-Fitr celebration in Villa Park

- Read the Encyclopedia of Chicago entries on Muslims, Bosnians, Egyptians, Palestinians, Syrians, and Pakistanis

- Listen to oral history interviews from our project American Medina: Stories of Muslim Chicago

- View images that were featured in our past exhibition American Medina: Stories of Muslim Chicago

In 1987, Congress officially designated March as Women’s History Month to commemorate, learn about, and reflect on women who have been history makers on their own terms. Chicago has had its fair share of influential women who have shaped not only the city, but the entire nation through their activism and work. In an effort to bring these narratives to the forefront, we’re proud to present this reader highlighting stories, exhibitions, and resources from the Chicago History Museum that elevate the stories of three of Chicago’s most notable women in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—Lucy Parsons, Jane Addams, and Ida B. Wells-Barnett—in one convenient place.

Portrait of Mrs. Lucy E. Parsons, arrested for rioting during an unemployment protest at Hull-House in Chicago, January 18, 1915. DN-0063954, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

Lucy Parsons (1851–1942)

Supposedly once described by the Chicago Police Department as “more dangerous than a thousand rioters,” Lucy Eldine Gonzales Parsons was a labor activist and organizer, a renowned orator, and perhaps most controversially during her time, a person of mixed heritage who claimed Mexican and Indigenous ancestry. She was the widow of Albert Parsons, one of the men hanged for his role in the Haymarket Affair.

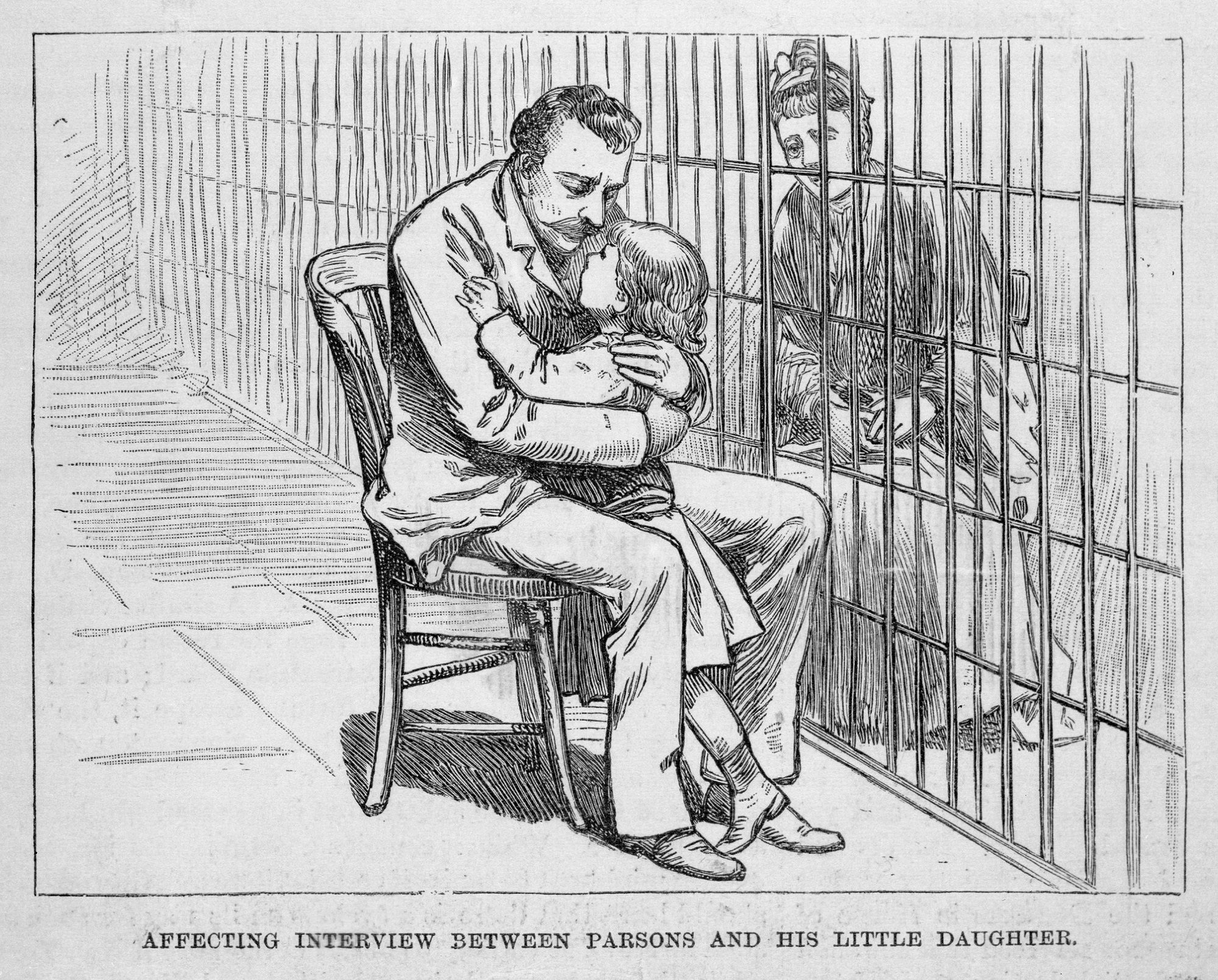

Sketch titled “Affecting interview between Parson’s and his little daughter” showing Albert Parsons hugging daughter in jail after Haymarket Affair arrest, Chicago, 1887. Published in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, November 12, 1887. CHM, ICHi-003672

Blog Post

CHM curatorial intern Brigid Kennedy’s blog post “A Fighter for Workers’ Rights” recounts the life of labor organizer Lucy Parsons.

The Dramas of Haymarket

This project highlights holdings from CHM’s collection related to the events before, during, and after the riots of 1886.

Chicago History magazine, vol. 15, no. 2 (summer 1986)

Parsons is mentioned numerous times in this issue highlighting her work as a publisher and radical organizer following the execution of the Haymarket martyrs. This entire issue is dedicated to the history and legacy of the Haymarket affair in the city.

Studs Terkel Radio Program about Labor History and Lucy Parsons

Listen as Studs Terkel talks with Irwin St. John Tucker about socialist causes in Chicago and historian Carolyn Ashbaugh about her book Lucy Parsons: An American Revolutionary.

Studs Terkel Radio Program about the Haymarket Affair

Studs Terkel talks with authors and historians Bill Adelman, Paul Avrich, Carolyn Ashbaugh, and Bill Neebe, the grandson of Haymarket defendant Oscar Neebe. The interviewees create a timeline of the events leading up to the Haymarket Affair including the German immigrants’ living situations, unions and strikes, and police brutality and corruption.

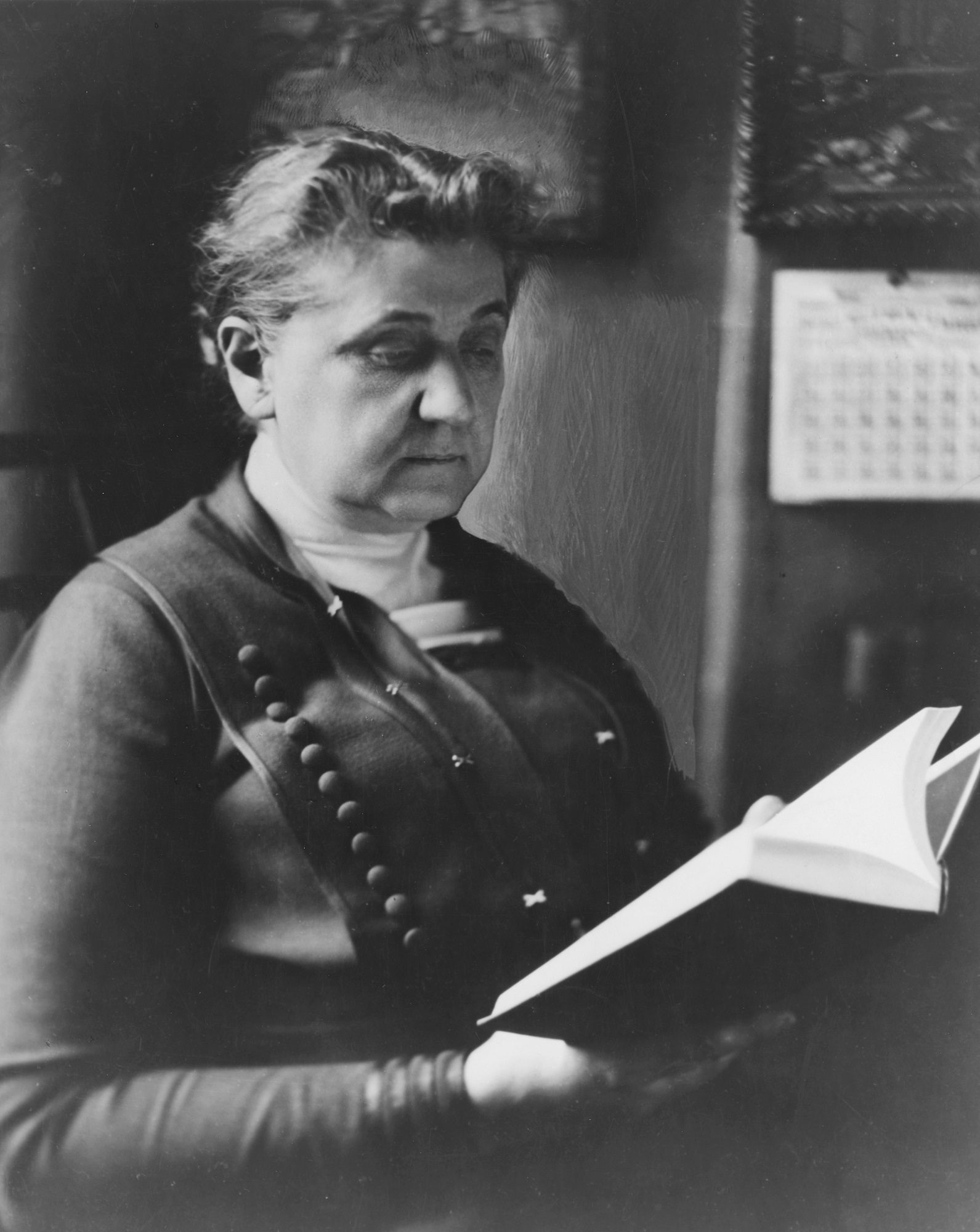

Portrait of Jane Addams, seated, reading a book, 1915. CHM, ICHi-026679

Jane Addams (1860–1935)

Jane Addams was a woman of many hats. In her role leading Hull-House, the Nobel Peace Prize winner and author was a social worker, housing activist, public health advocate, and the subject of an FBI investigation for so-called suspicious, and potentially treasonous, activities. Under her leadership, Hull-House became the most important settlement house in the United States.

Exterior view of Hull-House, Chicago, c. 1905. CHM, ICHi-019228; Barnes-Crosby Company, photographer

Digital Chicago – Jane Addams: Chicago’s Pacifist

In this digital project led by Professor James J. Marquardt of Lake Forest College, learn about Jane Addams’s lesser-known international peace advocacy before, during, and after World War I.

Encyclopedia of Chicago – Hull-House

Read the Encyclopedia of Chicago entry on Hull-House, Chicago’s first and the nation’s most influential settlement house, which was established by Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr on the Near West Side on September 18, 1889. Also included is an excerpt from Addams’ memoir, Twenty Years at Hull-House.

Chicago History magazine, vol. 12, no. 4 (winter 1983‒84)

The essay “Hull-House as Women’s Space” by Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz presents an in-depth analysis of the importance that the architecture of Hull-House had for its residents.

Studs Terkel Interview with Jessie Binford

Jessie Binford was a social worker who worked closely with Jane Addams at Hull-House. Listen as she talks with Studs Terkel about Addams’s life, the creation of Hull-House and the associated buildings, and how deeply in need they were of the help.

Portrait of Ida B. Wells-Barnett, 1920. CHM, ICHi-012867

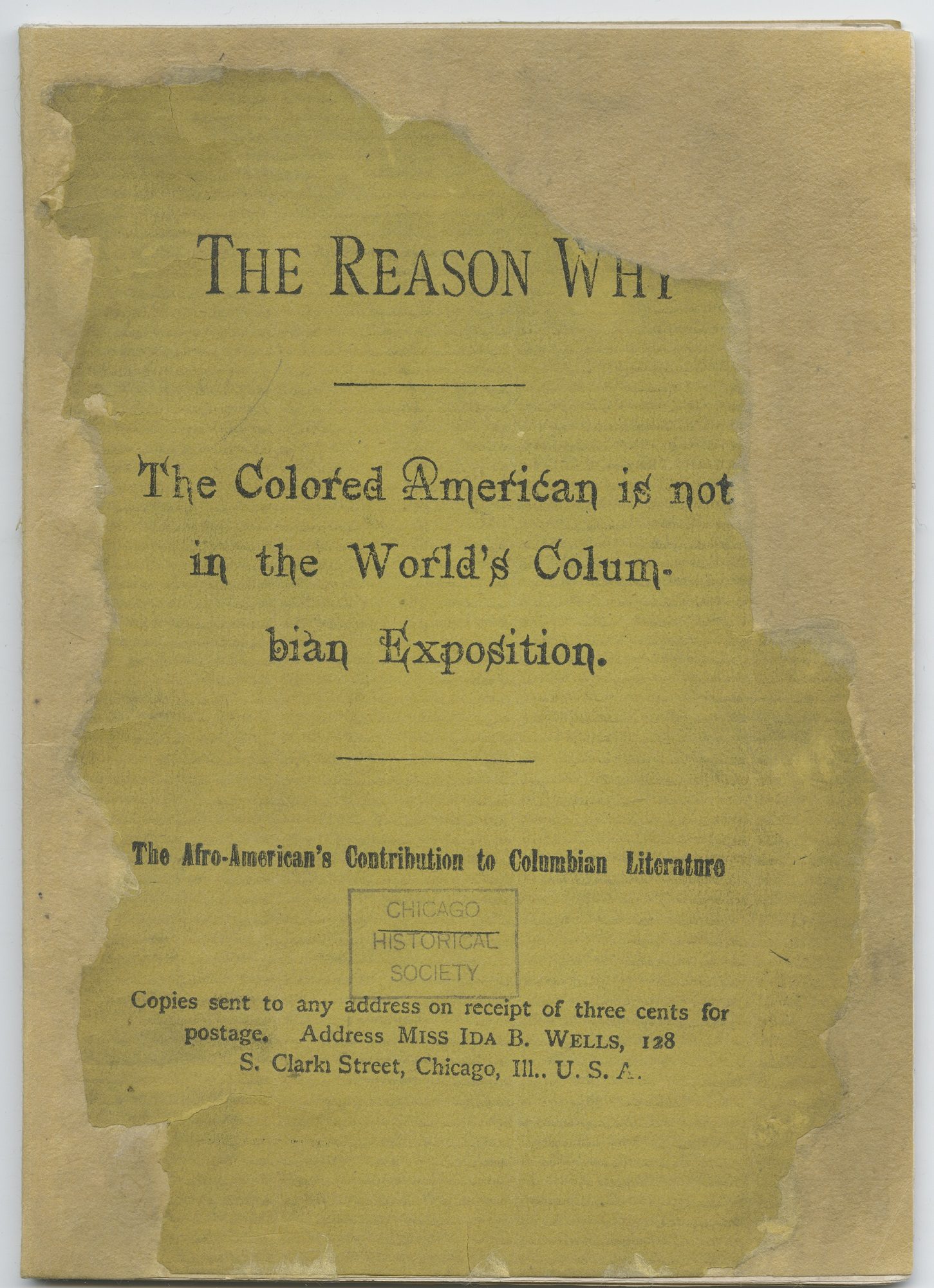

Ida B. Wells-Barnett (1862–1931)

Born enslaved in Mississippi during the Civil War, Ida Bell Wells spent her career as a journalist protesting and investigating lynchings, which ultimately brought her to Chicago for her own safety. It would be here that she would take her activism to a global stage, speaking to audiences abroad about the horrors of the Black experience in America. At home, she continued her work as a reporter and used influence to lobby for women’s rights issues, especially for non-white women.

Cover of the booklet The Reason Why the Colored American is not in the World’s Columbian Exposition: The Afro-American’s Contribution to Columbian Literature, by Ida B. Wells, published in Chicago, 1893. CHM, ICHi-040939

Democracy Limited: Chicago Women and the Vote

As one of the staunchest defenders of democracy during her time, the multifaceted story of Ida B. Wells-Barnett is present in a number of the modules that make up this online experience about women’s activism in Chicago to secure the right to vote—and beyond.

The Voids Project Zine

As a supplement to Democracy Limited, this zine was put together by a group of teens from across Chicagoland to document the social and organizing work of prominent Black women in Chicago, including Ida B. Wells-Barnett, and the places they supported.

Chicago History magazine, vol. 25, no. 3 (fall 1996)

The essay “The Brotherhood” by Beth Tompkins Bates chronicles the early work in organizing the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. This organization drew on the efforts of many of Chicago’s women social activists, such as Irene McCoy Gaines, Mary McDowell, and Ida B. Wells-Barnett.

Studs Terkel Interview with Alfreda Wells

Listen as journalist Studs Terkel speaks with Alfreda Wells, the youngest child of Ida B. Wells-Barnett, about her mother’s life and work as an investigative journalist and strong champion of civil and women’s rights.

Additional Resources

Beyond Parsons, Addams, and Wells-Barnett, Chicago history is full of women who made history their own.

Walking Tour | Democracy Limited – Chicago Women & the Vote

Go at your own pace and see where history was made here in Chicago.

Facing Freedom in America Exhibition

The Votes for Women collection contains a number of primary source materials that help interpret the contributions and leadership of Chicago women to a number of struggles in the fight for equality and suffrage.

CHM Blog – Women’s History

Explore the “women’s history” tag on CHM’s blog to read more stories of local women who made history.

To mark the start of Lent, CHM curator of religion and community history Rebekah Coffman talks about the meaning of ashes on Ash Wednesday and shares a brief history of Chicago’s Holy Name Cathedral.

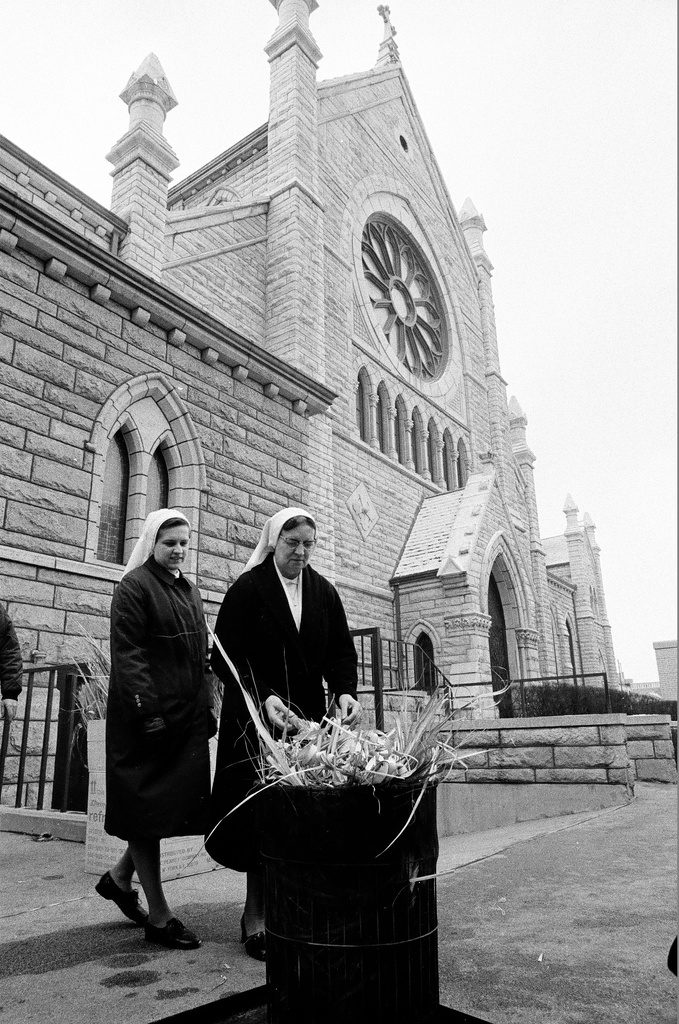

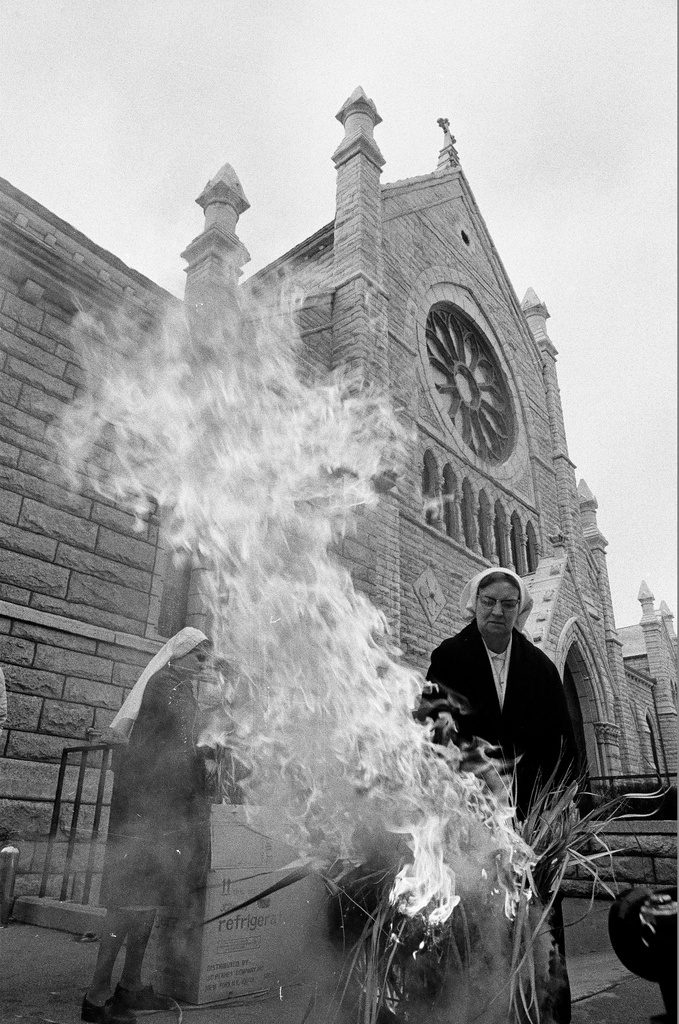

Sister Laurienne Normand (right, wearing glasses) burning palms for Ash Wednesday at Holy Name Cathedral, 730 N. Wabash Ave., Chicago, 1975. ST-40002014-0015, ST-40002014-0009, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM.

Wednesday, February 22, 2023, marks the beginning of the Lenten season for many Christians. Beginning on Ash Wednesday, Lent is observed for forty days as a time of introspection, symbolic fasting, personal sacrifice, and preparation for Easter Sunday. In Catholicism, this takes form through abstaining from eating meat on commemorative days and Fridays.

Ash Wednesday mass at Holy Name Cathedral, Chicago, 1971. ST-60000886-0018, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM.

Ash Wednesday derives its name from the ritual of a priest or pastor ceremonially placing ashes on the foreheads of worshippers, often in the shape of a cross. This is accompanied by saying, “Remember that you are dust, and unto dust you shall return,” a nod to the Biblical verse Genesis 3:19 and reminiscent of the phrase often spoken at Christian funerals “ashes to ashes and dust to dust.” The ashes used in services come from burned palm branches and have material symbolism. In Christian tradition, the palm is closely associated with the person of Jesus through the biblical story of his entry to Jerusalem commemorated on Palm Sunday, with the palm branch itself an ancient symbol of victory, peace, and eternal life.

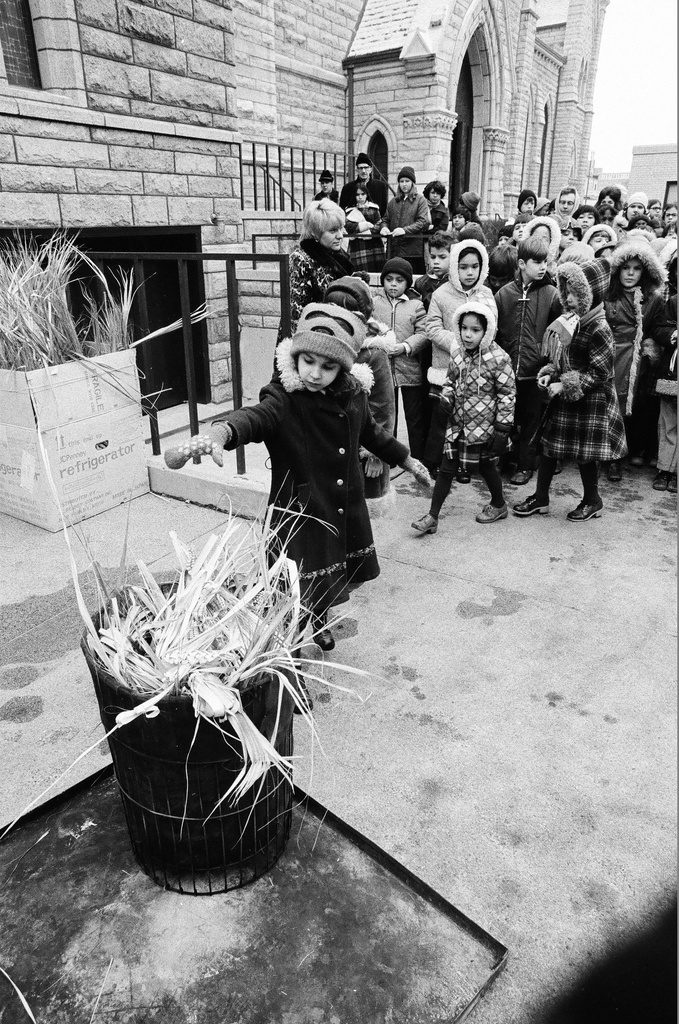

Priest and nuns along with schoolkids, burning palms for Ash Wednesday at Holy Name Cathedral, Chicago, 1975. ST-40002014-0004, ST-40002013-0014, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM.

Palm branches used in celebrating Palm Sunday are saved from the previous year and then ritually burned to create ashes for the next year’s services. Holy Name Cathedral in Chicago’s Near North Side neighborhood has held an annual “burning of the palms” event the Tuesday before Ash Wednesday for decades. Saved palms are brought to Holy Name’s courtyard on “Shrove Tuesday” (also known as “Fat Tuesday”), a day that celebratorily bridges the passing of the last year into the reflective start of Lent the next day. In a 1975 Chicago Defender article, Rev. James. J. Jakes of Holy Name notes the burning of palms as symbolic for the “burning out of our lives those things that [should] not be there.”

Hand-colored slide showing the exterior of the Church of the Holy Name ruins after the Great Chicago Fire, c. 1871. CHM, ICHi-176633.

The symbolism of renewal through ashes is very fitting for the legacy of Holy Name Cathedral. As the present seat of the Archdiocese of Chicago, it is the central church for one of the largest Roman Catholic Diocese in the country. The Chicago Diocese was founded in September 1843, just months after the city was formally established, and the Catholic community grew rapidly in tandem with the city. Just a few decades later, Holy Name’s predecessor congregations, the Cathedral of St. Mary and Church of the Holy Name, lost their buildings to the Great Chicago Fire of 1871.

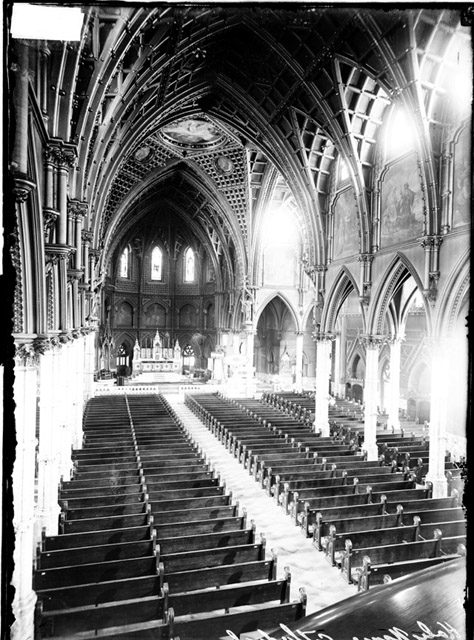

Holy Name Cathedral exterior and interior at 730 N. Wabash Ave., Chicago, 1909. DN-0007701 and DN-0007835, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM.

As the city itself is often compared to a phoenix rising from the ashes, so, too, is Holy Name in its postfire manifestation. For four years, the congregation met in a repurposed space while a new building was conceived and fundraised. By 1874, a stunning Gothic Revival structure arose from the former church site at State Street and Huron. Dedicated in 1875, the new Holy Name building was designed by Irish American Patrick Charles Keely, a favored architect of the American Roman Catholic Diocese who designed more than 600 churches, including a number of cathedrals. Keely looked to European stylistic trends purported by figures such as Augustus Pugin and John Ruskin to create an architectural language steeped in contemporary reinterpretations of medieval design. At Holy Name, the sanctuary’s wood interior is meant to recall the biblical Tree of Life through soaring archways and elaborate tracery.

Left: Renovation work being done on Holy Name Cathedral, 1969. ST-80004678-0012, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM. Right: Holy Name Cathedral, 2022. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman.

Holy Name has undergone several repairs and alterations since its construction, including a massive renovation in 1968–69 to align the worship space with post-Vatican II theological shifts. More recently, fire and ash again took hold as repair work to the church’s ceiling in 2008–2009 resulted in an accidental attic fire. Five circles in the ceiling hold symbolic images, with the largest now featuring the Greek monogram “IHS” for the name of Jesus over the image of a phoenix. Holy Name states this choice of imagery as a multilayered symbol: for the death and rebirth of the cathedral building, for the city of Chicago, and the symbolic death and resurrection of Jesus as remembered throughout the Lenten season.

Additional Resources

- See more images of Holy Name Cathedral

- Listen to Studs Terkel discuss church architecture with William Cooley, a church architect, and Martin E. Marty, a theologian and scholar at the University of Chicago

- Read the Encyclopedia of Chicago entry on Roman Catholics

In 1913, a sturdy brick and limestone building was completed and opened to the public; standing at five stories tall, what would come to be known as the Wabash Avenue YMCA was the result of community fundraising from area residents and the Chicago philanthropist Julius Rosenwald of Sears, Roebuck & Co. fame. While the building served as a job training center, temporary housing for stockyard workers, and of course a center for physical recreation in a segregated city, the Wabash YMCA’s most enduring legacy comes from its association with Dr. Carter G. Woodson.

Exterior view of YMCA of Metropolitan Chicago Wabash Avenue Building with addition in the Douglas community area of Chicago, c. 1940. CHM, ICHi-174453

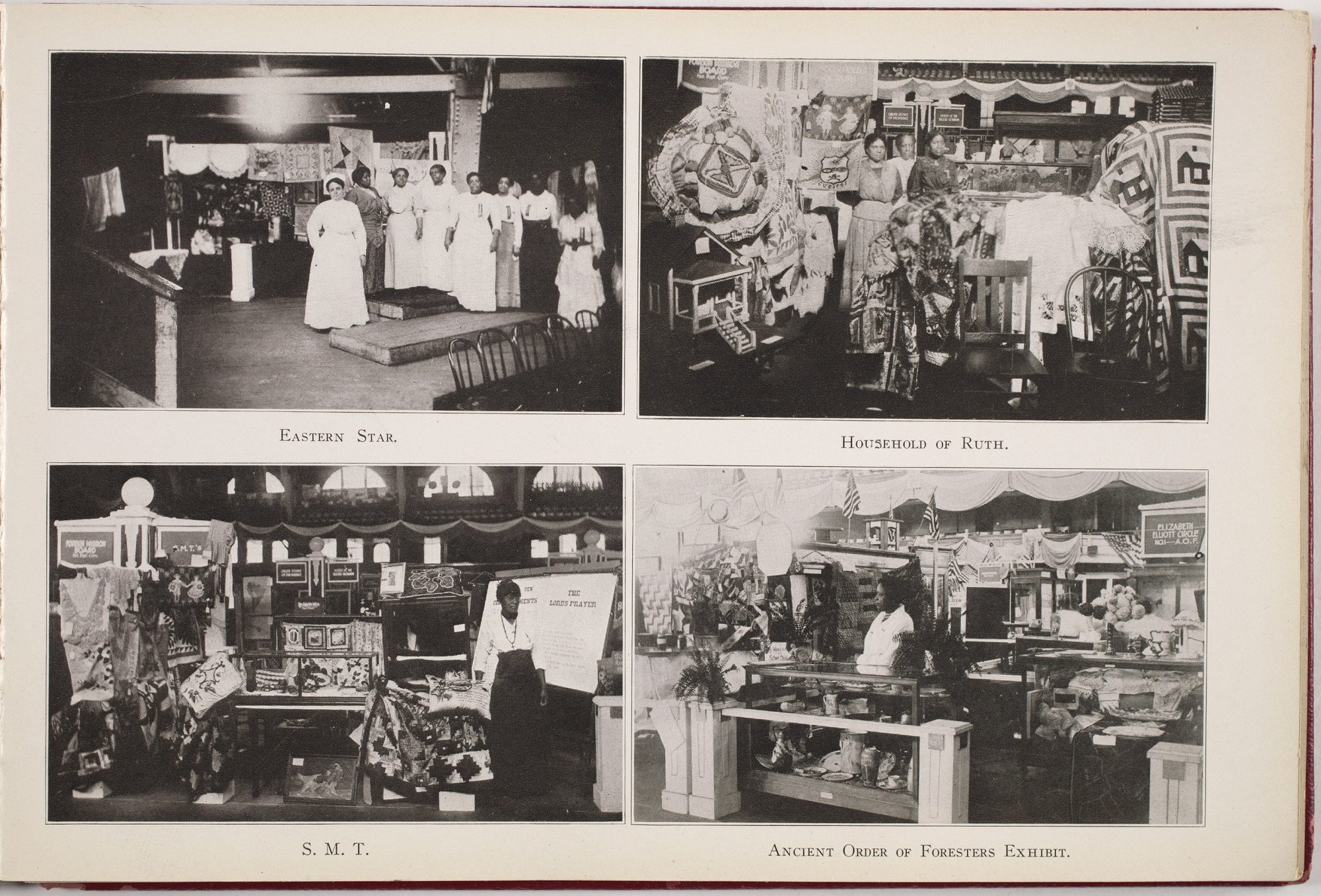

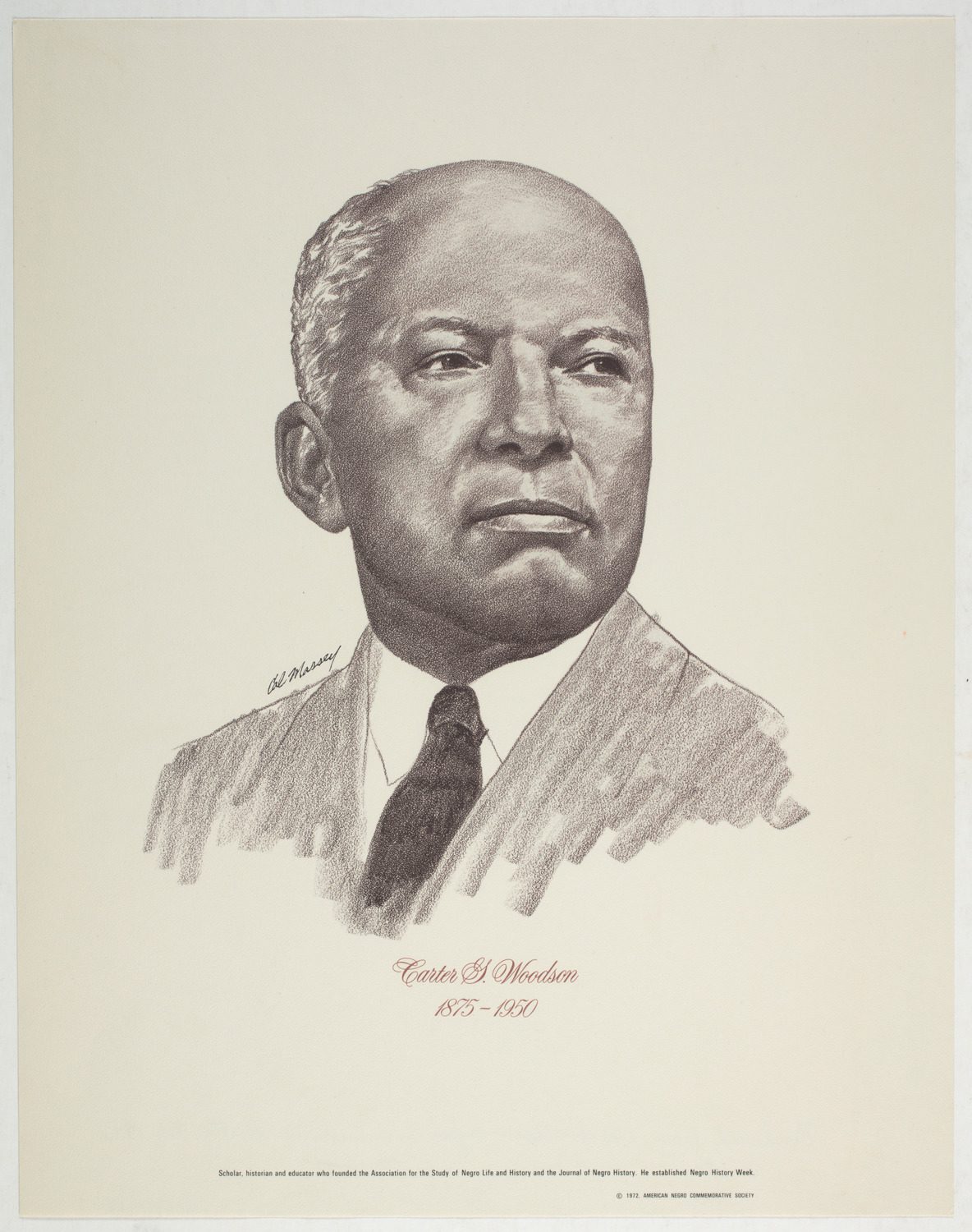

Born to formerly enslaved parents in 1875 in Virginia, Woodson would go on to graduate from the University of Chicago in Hyde Park and receive his doctorate in history at Harvard University in 1912. Three years later, in the summer of 1915, Woodson traveled to Illinois to attend the National Half Century Anniversary Exposition and The Lincoln Jubilee: 50th Anniversary Celebration. This exhibition in Chicago celebrated the semicentennial of the emancipation of enslaved African Americans in the US, highlighting the work and contributions to the nation by Black Americans across every aspect of society. In September of that year, Woodson convened a meeting with local leaders to form the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (ASNLH, known today as the Association for the Study of African American Life and History) at the Wabash YMCA, with the goal of promoting Black history across Illinois and the US through educational programs and print materials.

Page featuring photographs (clockwise from top left) of the Eastern Star, Household of Ruth, S.M.T., and Ancient Order of Foresters Exhibit at the National Half Century Anniversary Exposition and Lincoln Jubilee, Coliseum, Chicago, August 22‒September 16, 1915. Published in the Lincoln Jubilee Album: 50th Anniversary of Our Emancipation, compiled by John H. Ballard, 1915. CHM, ICHi-174447; John H. Ballard, photographer

Portrait drawing, c. 1972, of Carter G. Woodson, scholar, historian, and educator. CHM, ICHi-031431; Cal Massey, artist © 1972 The American Negro Commemorative Society

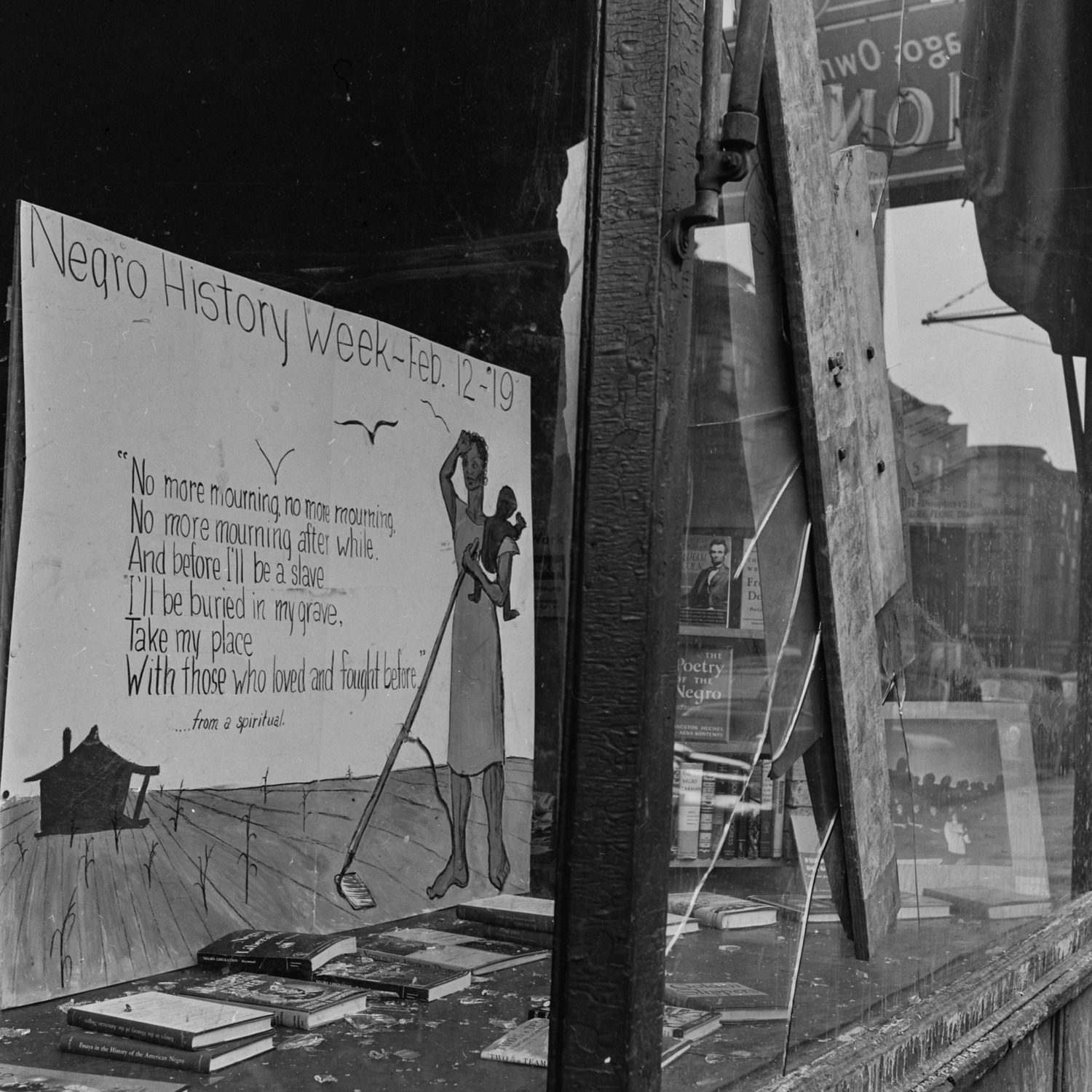

Black History Month had a number of other iterations before it was a month-long celebration. It began in 1924 as “Negro History and Literature Week” and then was renamed “Negro Achievement Week.” The third and final name change would come in 1926, when a press release came forward announcing the celebration of “Negro History Week.” Woodson’s History Week received much fanfare across the country, since, due to the Great Migration, population numbers for Black Americans boomed across urban areas in the US. This meant a desire to adopt Woodson’s teachings and mission into school curricula and social clubs.

Sign for “Negro History Week” in the storefront window of Community Book Shop owned by Joan Place at 1404 E. 55th St., in the Hyde Park neighborhood of Chicago, February 1951. CHM, ICHi-087088; Mildred Mead, photographer

During all this movement, Chicago and the Wabash YMCA remained among the intellectual centers for Black History. Fortunately, the ASNLH counted among its ranks a Black librarian named Vivian G. Harsh, who worked for the Chicago Public Library system and who would eventually create one of the most robust archival Black history collections in the country, collecting books, ephemera, and other forms of cultural material related to the Black experience in the US. Harsh’s collection proved indispensable to the dissemination of knowledge for Woodson’s Negro History Week.

Woodson died following a heart attack in April 1950. He is interred at Lincoln Memorial Cemetery in Maryland. Twenty-five years after his passing, the Chicago Public Library system honored Woodson’s memory by opening a branch named after him on the South Side. This branch would also come to house the Vivian G. Harsh Collection of Afro-American History and Literature, ensuring that the collection and all its treasures would remain accessible to all those interested in Black history.

Federal recognition for Woodson’s celebration of Black history came a half century later, when during the 1976 celebration of the US Bicentennial, President Gerald R. Ford proclaimed every February to be designated as Black History Month. Ironically, Woodson hadn’t expected Black History Month to be a long-term observance, as he hoped Black history would simply be included as part of our national educational curriculum. The Wabash YMCA received its own recognition a decade later, when it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Today, the building is owned by The Renaissance Collaborative (TRC), a multifaith community organization that purchased the building while it was in a state of disrepair in the 1980s and, after a restoration, has turned the building into an affordable housing apartment complex, saving it from demolition.

Today, Black History Month is a national celebration that continues to honor the legacy of Black Americans and their contributions, whether scientific, cultural, or intellectual, to American society. While it serves as a time to look back and reflect on often complicated histories, it also offers an opportunity to reflect on possible futures.

Additional Resources

- Take a virtual tour of the Wabash YMCA

- Learn more about Chicago’s early Black populations in our two-part Google Arts & Culture project “Concert is Power”: Part 1 and Part 2.

To mark the Lunar New Year, CHM curator of religion and community history Rebekah Coffman highlights a Year of the Rabbit item from our Asian American Small Business Association collection of visual materials.

Happy Lunar New Year! Sunday, January 22, 2023, marks the beginning of the Year of the Rabbit 4720/2023.

Lunar New Year celebrations have been an integral part of Chicago’s history for decades within and beyond Chicago’s Chinatown on the South Side. Also known as the Spring Festival, communities throughout Asia and the Western diaspora celebrate the turning of winter toward the coming spring. Darkness is symbolically combatted through representations of light via fireworks and lanterns. Delicious food such as glutinous rice cakes, dumplings, longevity noodles, and sweet rice dumplings are eaten to bring prosperity, longevity, good fortune, and a fresh start to the coming year. Throughout the two weeks of celebration, streets and community centers are filled with dances, parades, music, and other community and family gatherings.

Chinese New Year Parade Dragon in the Uptown neighborhood, Chicago, 1100 W. Argyle St., 1983. CHM, ICHi-037875; John McCarthy, photographer

Though celebrated within many diverse communities, Lunar New Year is often called “Chinese New Year” in part because its date is based on the traditional Chinese lunisolar calendar. Each year is sequentially represented by an animal from the zodiac over a twelve-year cycle (rat, ox, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, sheep, monkey, rooster, dog, and pig). Accordingly, we look to an example from a past Year of the Rabbit celebration within CHM’s collection.

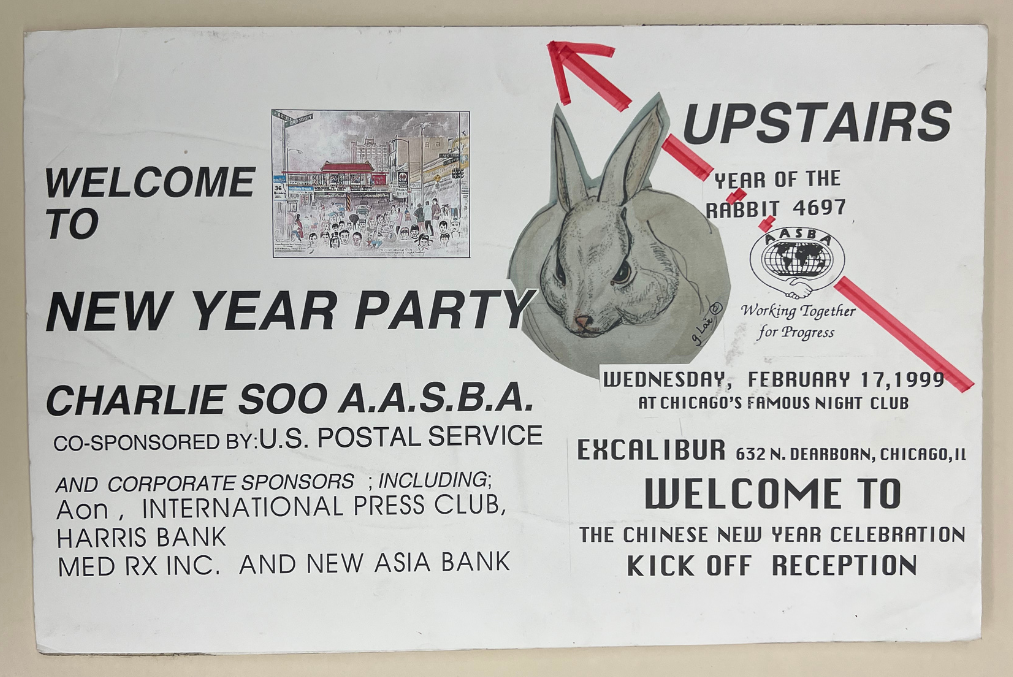

White poster on foam board for Year of the Rabbit 4697 New Year Party. CHM, 2001.0229 PPL; Asian American Small Business Association collection of visual materials, 1991–2001. Photograph by CHM staff

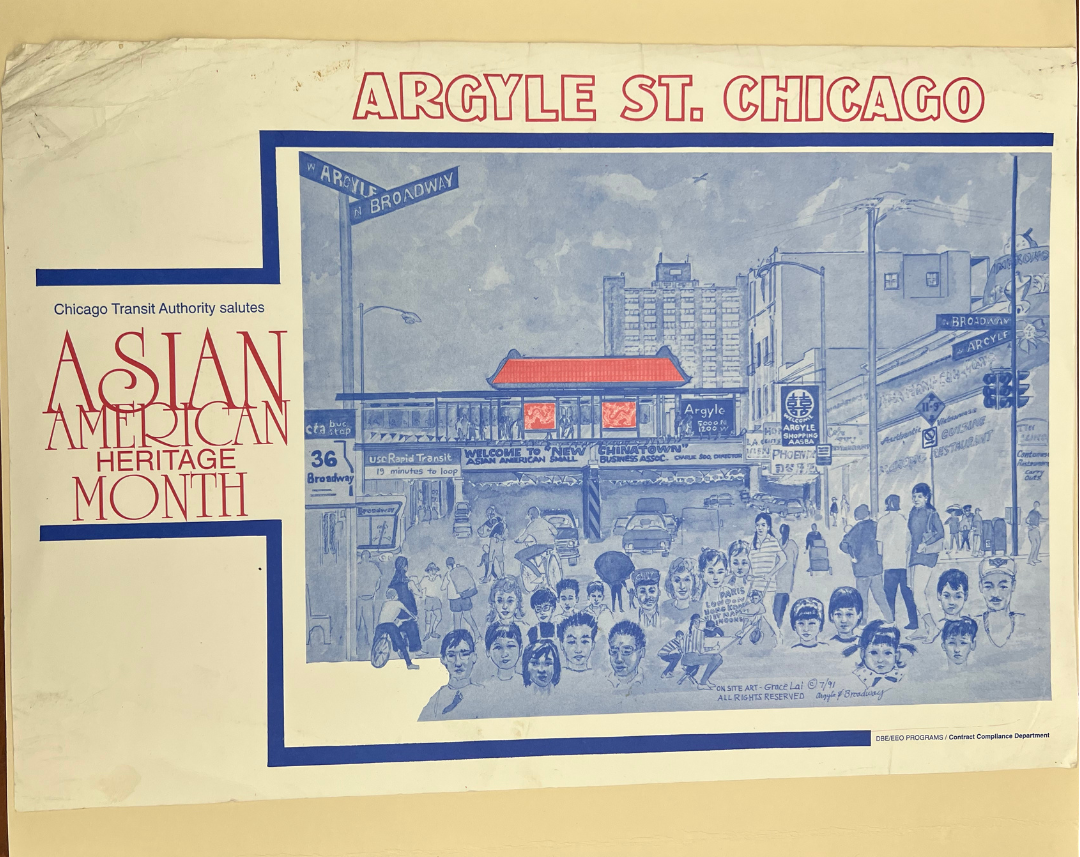

This welcome sign is from a Lunar New Year party held in celebration of the Year of the Rabbit 4697/1999 at “Chicago’s Famous Night Club” the Excalibur at 632 N. Dearborn (notably the former location of the Chicago Historical Society and today the Tao Restaurant and Nightclub). The poster features two reproductions of artworks created by Chicago-based watercolor artist Grace Lai, one appropriately of a rabbit and the other of the Argyle Street L platform, which features more prominently in this 1990s Chicago Transit Authority poster for Asian American Heritage Month.

Chicago Transit Authority Poster reading “Argyle St. Chicago: Chicago Transit Authority salutes Asian American Heritage Month.” CHM, 2001.0229 PPL; Asian American Small Business Association collection of visual materials, 1991–2001. Photograph by CHM staff

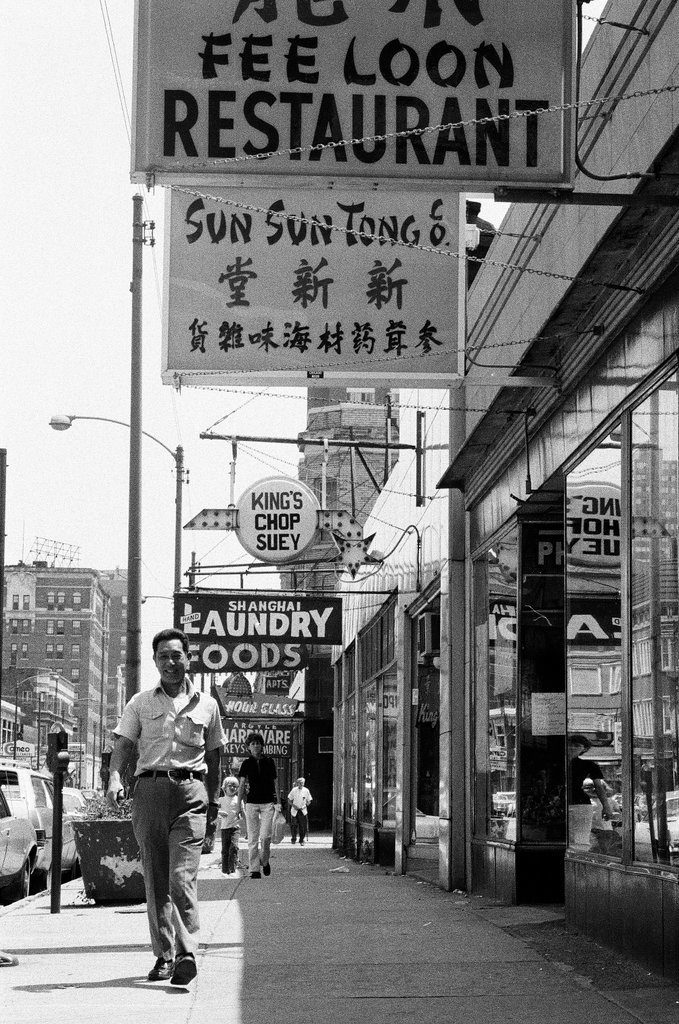

While the annual Lunar New Year party was held close to downtown, its sponsor—the Asian American Small Business Association (AASBA)—is more readily recognized for its roots as a community anchor organization in the city’s Uptown neighborhood. In the 1960s, well-known restauranteur Jimmy Wong envisioned a “New Chinatown” on Chicago’s North Side, in part to help alleviate spatial pressures from the ever-expanding historic Chinatown at Cermak Road and Wentworth Avenue. Wong, with other local entrepreneurs from the Hip Sing Association, established several businesses along Argyle Street.

Chinese restaurants and businesses on W. Argyle St. in the Uptown neighborhood, Chicago, 1975. ST-90003294-0012 and ST-90003294-0006, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

By the 1970s, the number of Asian American-owned restaurants, bakeries, shops, and social agencies in the area had grown substantially, and by 1979, under the leadership of Charlie Soo, the AAASBA was born.

Owner, Eric Cheng, standing in front of Sun Wah Barbeque Company at 1134 W. Argyle St., Chicago, 1987. CHM, ICHi-036667; James Newberry, photographer

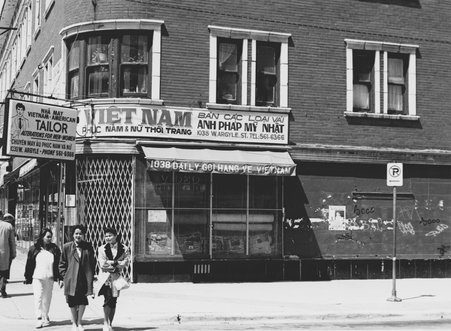

The goal of the AASBA’s founder was not just to create a thriving business center, but to attract young Asian community members to live in the Argyle area, a legacy found through a group of Chinese, Vietnamese, Hmong, Cambodian, and Laotian families, businesses, and community organizations over subsequent decades, with many coming to Chicago as refugees. Known today as “Asia on Argyle,” these few blocks have also been given the moniker “Little Vietnam” because of its vibrant Vietnamese presence.

Women walking in front of Vietnam-American Tailor storefront at 1038 W. Argyle St., Chicago, 1987. CHM, ICHi-040734

Charlie Soo, known as the unofficial “Mayor of Argyle Street,” worked for more than two decades until his death in 2001 to create a thriving economic center through community-centered grant projects, including a major renovation of the Argyle L train station and establishing community celebrations and events such as the Taste of Argyle. An inheritance of these collective efforts, the annual Argyle Lunar New Year Parade and Celebration has been held on area streets since 1981 and continues today.

Additional Resources

- See the Asian American Small Business Association papers in the Abakanowicz Research Center, which is free to visit

- Read the Encyclopedia of Chicago to learn more about Chicago’s Asian communities: Chinese, Vietnamese, Cambodians, Laotians, Hmong, Uptown, Chinatown

January 11 is marked on the calendar as National Milk Day, commemorating the day the first glass bottled milk deliveries began en masse in the US, starting with the state of New York in 1878. And while Chicago’s strongest bovine association has been to the Union Stock Yard, the dairy industry was also a lucrative entity across the city that employed thousands.

Milkman making a delivery for the Bowman Dairy Company using a horse-drawn milk delivery wagon on a residential street, Chicago, 1914. CHM, ICHi-067268

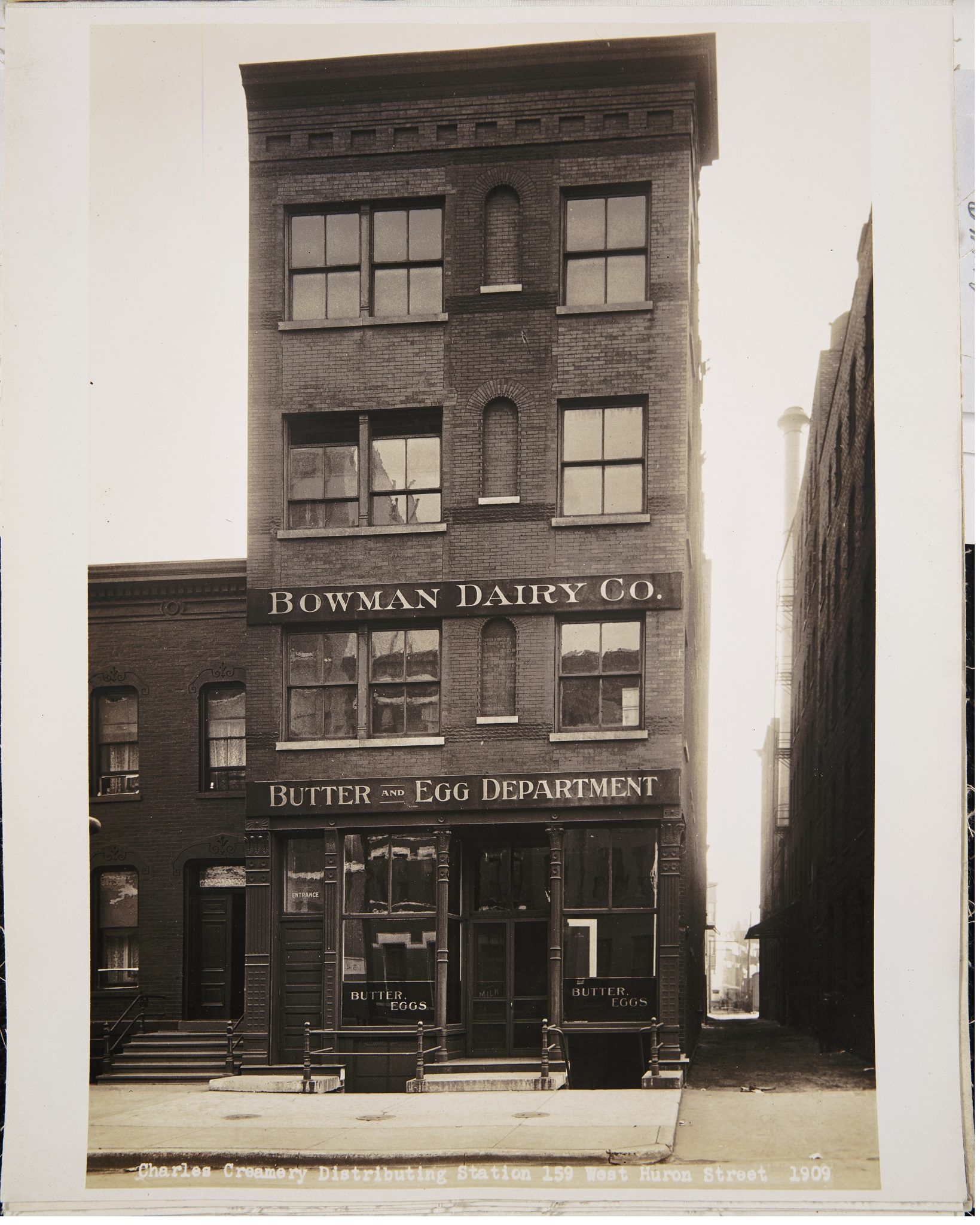

The kings of the Chicago dairy industry were undoubtedly the operators behind the Bowman Dairy Company, who were the largest distributors of milk in the city through the first half of the twentieth century. The company began in 1874 under Johnston R. Bowman in St. Louis. By 1891, company leadership consolidated by selling the St. Louis operation for $110,000, which, adjusted for inflation, is just over $3.4 million in 2022. From that point on, all operations would be headquartered in Chicago, after the acquisition of a local operator, the Jersey Milk Company. A further partnership (and eventual buyout in 1898) with a local creamery further cemented Bowman’s presence in the city, as they became known for delivering freshly bottled milk across more than 30 commercial routes in the city, quickly developing a strong reputation amongst the city’s rapidly growing population.

Workers bottling milk at the Bowman Dairy Company, Barrington, Illinois, 1914. CHM, ICHi-068768

One of the many factors that brought the company success was its pioneering efforts in delivering pasteurized milk and cream by 1899. This was achieved by a partnership with farms in the Chicago suburbs. Their milk and cream would be delivered via rapid train in the morning to the bottling and distribution centers that Bowman operated across the city, where workers and deliverymen were ready for their daily routes. Chicago passed its first pasteurization law in 1908, making Bowman’s practices for milk delivery the industry standard.

A line of Bowman Dairy trucks and drivers outside of a Bowman Dairy building, Chicago, 1915. CHM, ICHi-020259

By 1920, the company was strong enough to acquire another significant local competitor, the Kee & Chapel Dairy Company, which ultimately landed Bowman with expanded operations across the city and nearly 300 commercial routes for milk distribution. It would then expand into the ice cream market by 1938 and would invest heavily into the popularity of the frozen treat, acquiring competitors in Chicago and outside of Illinois in Wisconsin and Ohio. By the middle of the century, along with their profitable dairy operation, the Bowmans officially expanded into the poultry business with the purchase of a poultry farm, thus inaugurating the aptly named “Bowman Dairy Company Egg Division” in 1947.

Charles Creamery Distributing Station for the Bowman Dairy Company, Butter and Egg Department, 159 W. Huron St., Chicago, 1909. Bowman initially partnered with a poultry farm for their venture into eggs and bought the farm when their attempt proved successful. CHM, ICHi-068763

The decline of the Bowman Dairy Company was gradual, beginning with antitrust lawsuits claiming that the company’s size was making it impossible to compete in the region. Changing consumer habits also greatly impacted the company’s efforts, with milk deliveries dramatically decreasing in popularity as dairy products continued to be found in greater supply across supermarkets and grocers. This was compounded by difficult negotiations with the union that represented milk deliverymen, who refused to take decreases in pay and delivery routes. Ultimately, the company and all its holdings would be sold to the dairy conglomerate Dean Foods in 1966. Up until its sale, Bowman remained family owned and operated, overseeing what the company called the “Bowman City,” a network of bottling, production, and distribution centers that brought milk to thousands of consumers across Illinois and the greater Midwest.

Additional Resources

- See more images of the Bowman Company’s operation across Illinois

- Access the Bowman Dairy Company records (1870–1972) at the Abakanowicz Research Center, which is free to visit

Interested in learning something new in 2023? In our latest blog post, CHM director of research and access Ellen Keith reveals the top five most requested collection items at the Abakanowicz Research Center in 2022.

What do people want to see in the Abakanowicz Research Center?

Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, so we freely confess we were inspired by our colleagues at the Newberry Library when they published The 5 Most-Requested Collection Items of 2022. We keep statistics too, so what were our researchers requesting in 2022? Our list is affected by an atypical year. For the first half of 2022, the bulk of our archival collections were inaccessible as we finished a much-needed storage renovation. You might think that what was most requested were the collections we were able to keep on-site the whole time, but no. Researchers made up for lost time, and two of the collections in the top five were those that had been unavailable earlier.

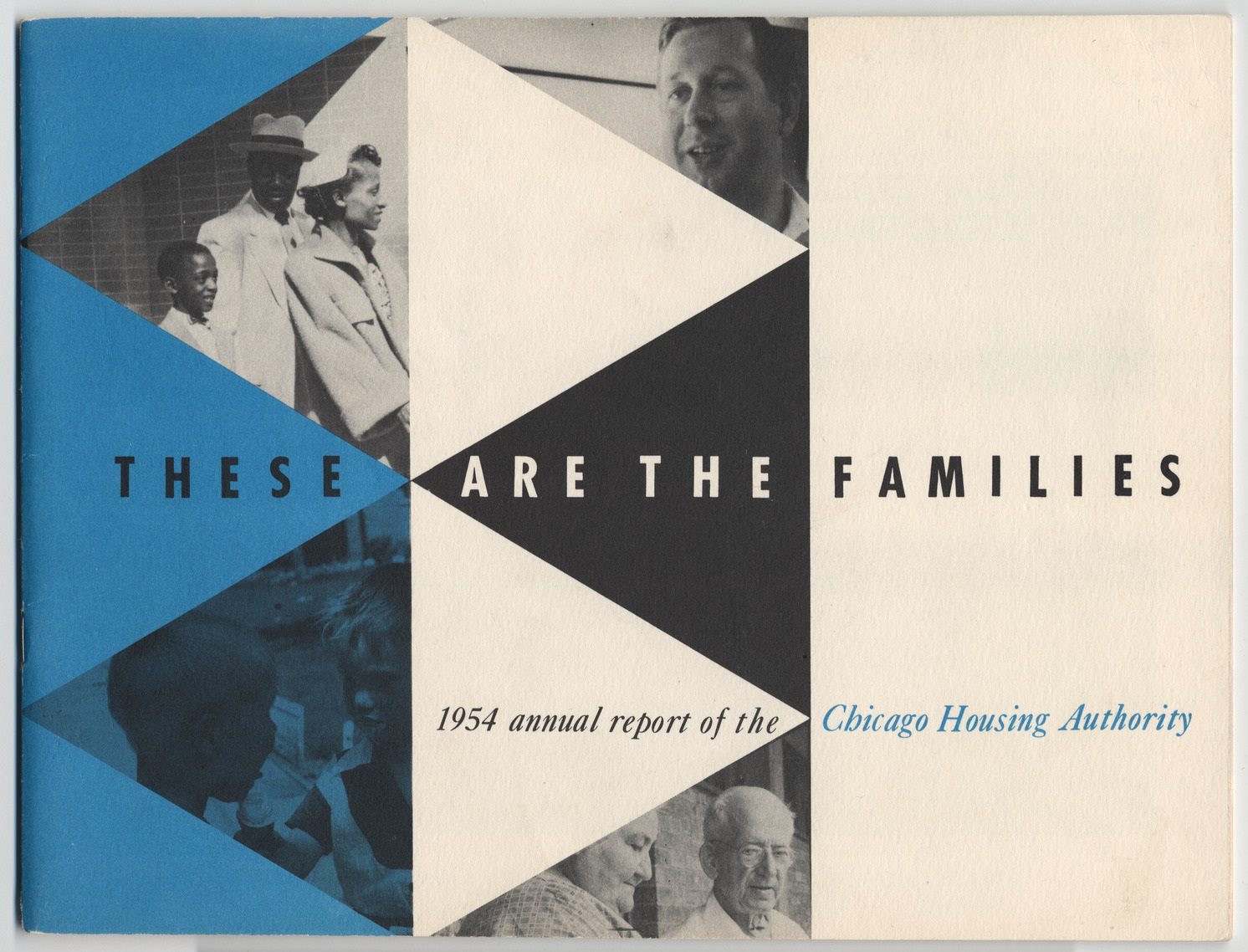

Front cover of These Are the Families, the 1954 annual report of the Chicago Housing Authority. CHM, ICHi-040474

#5 Chicago Housing Authority Development records, 1948–92

This 39-box collection was inaccessible until July but is a high-interest collection for urban historians. The Chicago Housing Authority is inextricably tied to Chicago’s history of segregation.

Members of the Mexican Community Committee of South Chicago meeting, Chicago, c. 1960s-70s. CHM, ICHi-174455

#4 Mexican Community Committee of South Chicago records, 1956–99 (bulk 1985–98)

We kept this collection on-site during the storage renovation for CHM curator Elena Gonzales to consult as she works toward the Aquí en Chicago exhibition scheduled for 2025. She wasn’t the only one who wanted it, though. We had several other researchers visit, just to see this collection.

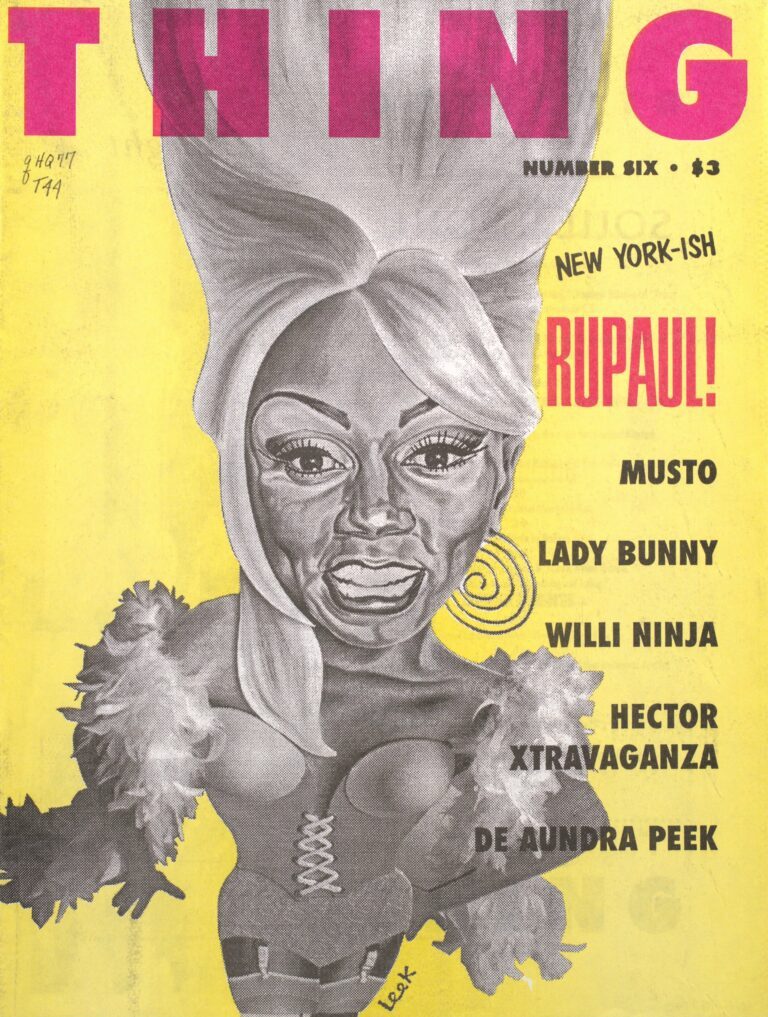

The back of a Thing magazine subscription card, c. 1990. Inserted in Thing no. 9, Spring 1993, p. 15, Chicago. CHM, ICHi-177029-002

#3 Thing magazine records, c. 1980–95, bulk 1987–94

This collection was processed in 2019, and project archivist Rebekah McFarland composed an illuminating Google Arts and Culture story. As it was so recently available and interest was high, we kept it on-site during the storage renovation, which spanned 2021–22. Chicago Reader reporter Leor Galil visited in 2021 to write a feature on the magazine.

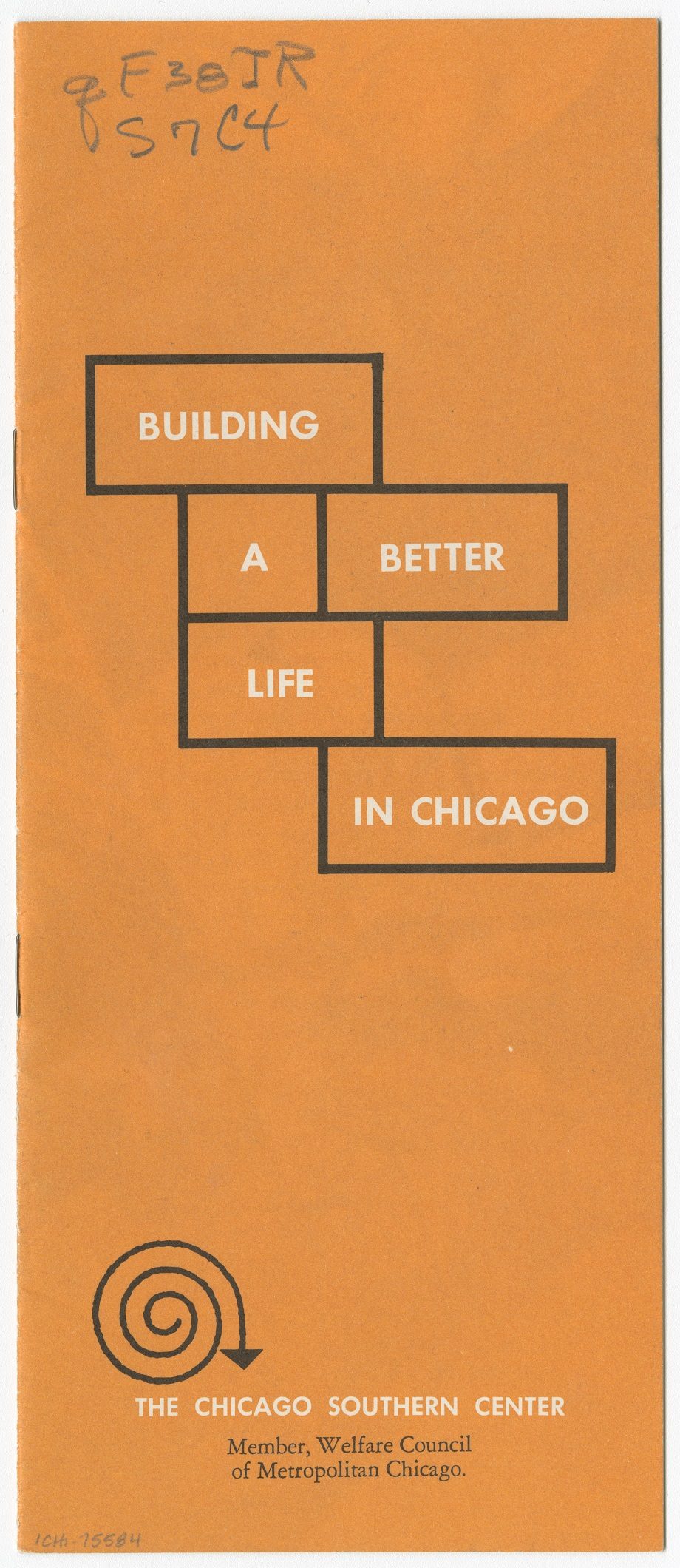

Front cover of a pamphlet titled Building a Better Life in Chicago, published by the Chicago Southern Center, a member of the Welfare Council of Metropolitan Chicago, 1967. CHM, ICHi-075584

#2 Welfare Council of Metropolitan Chicago records, 1914–78

This collection weighs in at a staggering 802 boxes, so it had to go off-site during the renovation. Its finding aid shows its members were a variety of agencies, so it has been a popular destination for researchers looking for social service organizations large and small.

A group of protesters rally against the Red Squad at the Richard J. Daley Center, 50 W. Washington St., Chicago, April 19, 1975. Studs Terkel stands in the center background, elevated. ST-14002131-0001, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

#1 Chicago Police Department Red Squad and related records [manuscript], c. 1930s–86, bulk 1963–74

No surprise here. This collection has been the most requested collection for the last ten years, except for 2015, when it came in second to Marshall Field & Company records, with donations from Federated and Target. We knew we had to keep all 205 linear feet of this collection on-site during the renovation. The collection is governed by a court order but can be accessed when researchers follow the protocols.

As a young girl, Rev. Christine V. Hides loved to read and dreamed of solving mysteries. Now Hides has helped the Chicago History Museum solve one. After visiting the Vivian Maier: In Color exhibition, she identified the location where Vivian Maier took a photograph after recognizing two stained glass windows in an image.

Rev. Christine V. Hides stands by the windows at the Kenilworth Union Church that appear in Maier’s photograph. Photograph by Eric Miller, 2022.

Hides, who serves as associate minister at Kenilworth Union Church, noticed the detail when viewing a photograph that showed people in a church hall. “I was so excited when I saw this image,” Hides recalled, “because the windows in the photo looked similar to two stained glass windows in our church designed by renowned glass artist Henry Lee Willet.”

People in a church hall, October 1974. The back wall appears different due to renovations to the church after the photograph was taken. CHM, ICHi-181323 / © The Estate of Vivian Maier

When she got home, Hides confirmed that the windows were the same. Then she visited CHM Images, our image portal, where she was able to find and identify more photographs taken at Kenilworth Union Church. Based on their content, it appears that Vivian Maier had visited the church during a rummage sale.

A woman wraps up a package for a customer at a rummage sale at Kenilworth Union Church, Kenilworth, Illinois, c. 1974. A variety of nightgowns hang in the background. CHM, ICHi-181333 / © The Estate of Vivian Maier

![A mirror at a rummage sale at Kenilworth Union Church, Kenilworth, Illinois, circa 1974. [This reference image may be cropped or require color correction and/or reorientation to reflect the original image.]](https://www.chicagohistory.org/app/uploads/2022/11/i181320_pm.jpg)

A mirror leaning against boxes of goods at a rummage sale at Kenilworth Union Church, Kenilworth, Illinois, c. 1974. CHM, ICHi-181320 / © The Estate of Vivian Maier

Thanks to Hides’s findings, Museum staff were able to update their metadata with the location of these sets of prints. “Vivian Maier focused her lens on people rather than the building,” Hides noted. “She captured ordinary moments that show how the church is woven into the fabric of the community.”

Additional Resources

- See Vivian Maier: In Color before it closes on Saturday, December 31

- View our Google Arts & Culture story Vivian Maier: Her Chicago

- Peruse images from CHM’s Vivian Maier photography collection, which comprises about 1,800 color negatives and transparencies

- Read the Chicago History magazine article “Looking Again” by Frances Dorenbaum, guest curator of Vivian Maier: In Color

Chicago has had more than its fair share of big band and jazz dance halls across the city to accommodate nearly everyone’s musical taste. On December 6, 1922—100 years ago—at 62nd Street and Cottage Grove, in the Woodlawn neighborhood, the Trianon Ballroom opened its doors and counted itself among the city’s nightlife destinations.

An undated photograph of the exterior of the Trianon Ballroom at Cottage Grove and East 62nd Street. The marquee reads: “Presenting Art Kassel & His Orchestra.” CHM, ICHi-050765

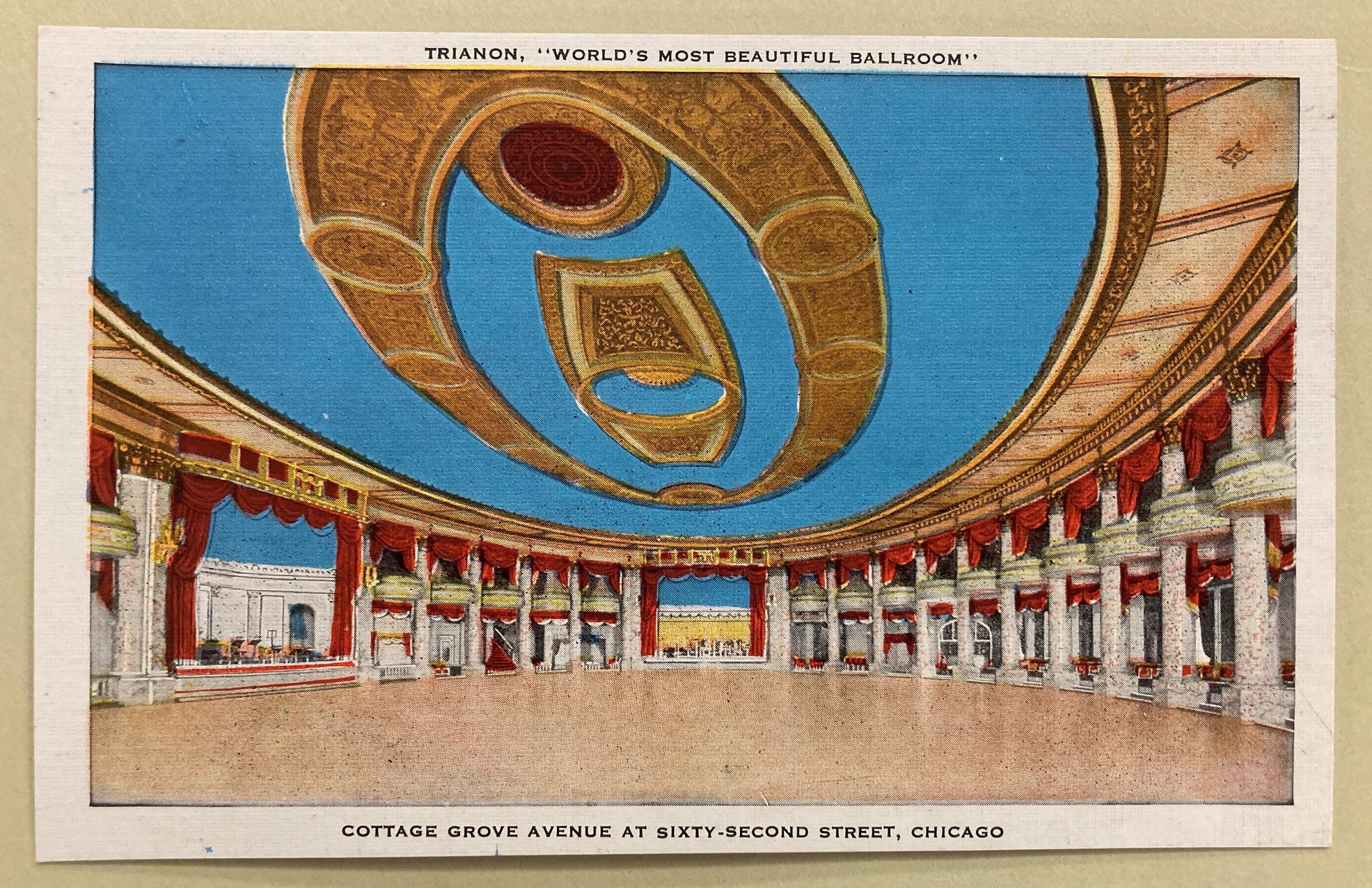

Marketed as the “World’s Most Beautiful Ballroom,” its name and décor were inspired by the Grand Trianon palace at Versailles, commissioned by Louis XIV. The dance hall was an enterprise of brothers Andrew and William Karzas, entrepreneurs in Chicago’s Greek community, who already owned a small chain of movie theaters across the city. When it opened, the Trianon was said to be able to accommodate up to 3,000 dancers at a single time on the main ballroom floor, which measured 100 by 140 feet. The venue also boasted being one of the few air-conditioned facilities in all of Chicago. When all was said and done, the estimated cost of opening the ballroom was $1.2 million (close to $21.3 million in today’s dollars). The venue’s opulence reflected its entertainment, as it brought the most popular names in big band and attracted Chicagoans from every walk of life, from working-class couples to elite socialites. In 1920s Chicago, the Trianon was the place to be.

Undated postcard of the “World’s Most Beautiful Ballroom.” Photograph by CHM Staff

To match its aesthetic reputation, the Trianon would be the first venue in the city with a strict dress code—coats and ties for gents, gowns for ladies. To enforce “appropriate” behavior, the venue employed a troop of “floor men” who were tasked with policing the room, keeping an eye out for dancers engaging in lewd or overly physical displays of affection. And for those with insufficient knowledge or two left feet, weekly dance classes were also held on-site. Of course, if patrons wanted to dance the jitterbug or dance along to some jazz, they’d be disappointed to know about the Trianon’s strict policy forbidding both.

Undated photograph of marble columns around the dance floor in the Trianon Ballroom at Cottage Grove and E. 62nd St. CHM, ICHi-050746

The success of the Trianon would inspire the Karzas brothers to try and catch lightning in a bottle twice with the opening of Trianon’s sister ballroom, the Aragon, four years later in 1926, which still operates to this day. Beyond big band dances, the Trianon would go on to have its own radio station, with the call letters of WMBB standing for “World’s Most Beautiful Ballroom.” The station went on the air in 1925, hoping to capitalize on the good reception the ballroom had received. The airwaves, however, were not meant to be and the station went permanently dark in 1928.

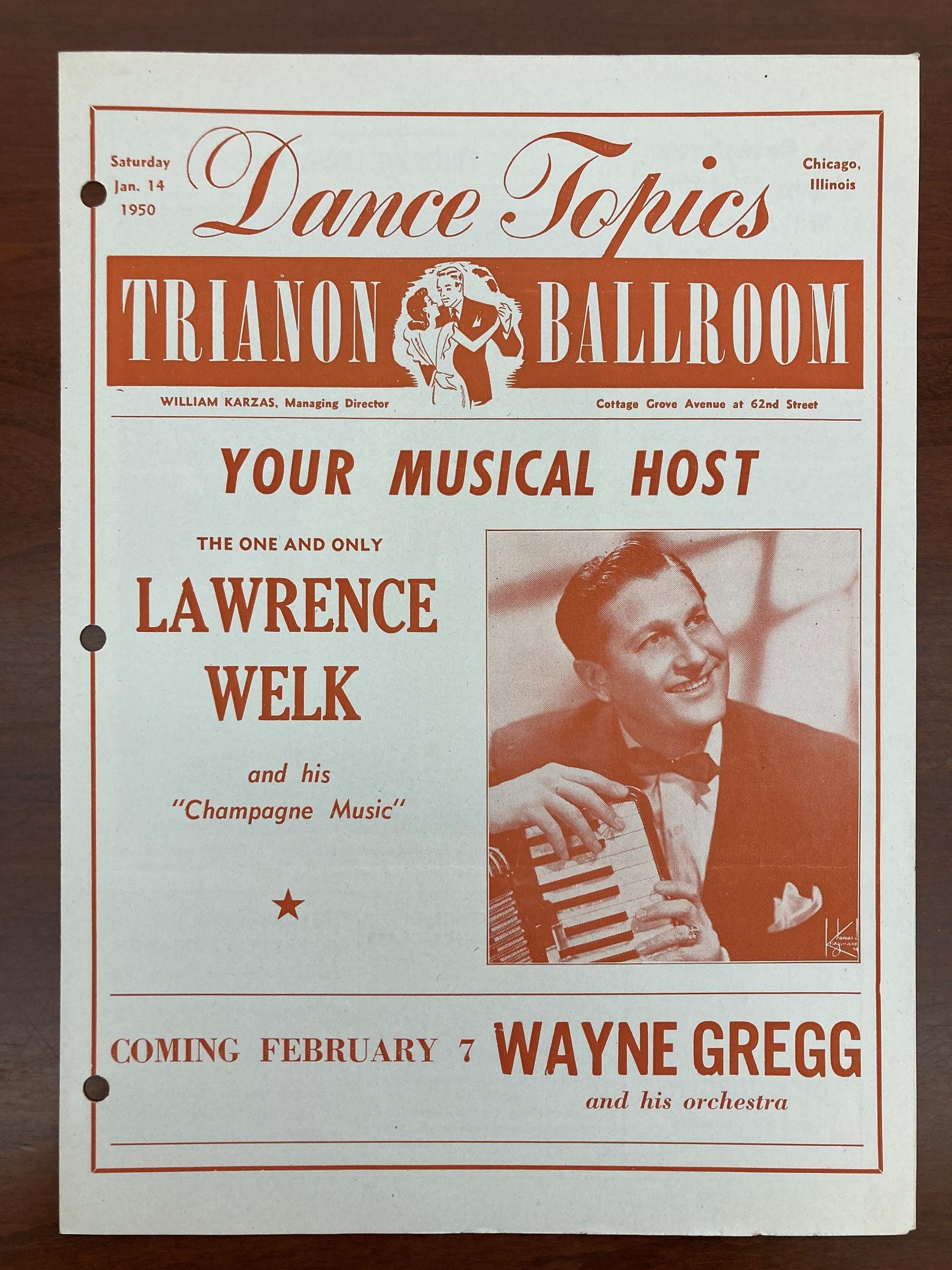

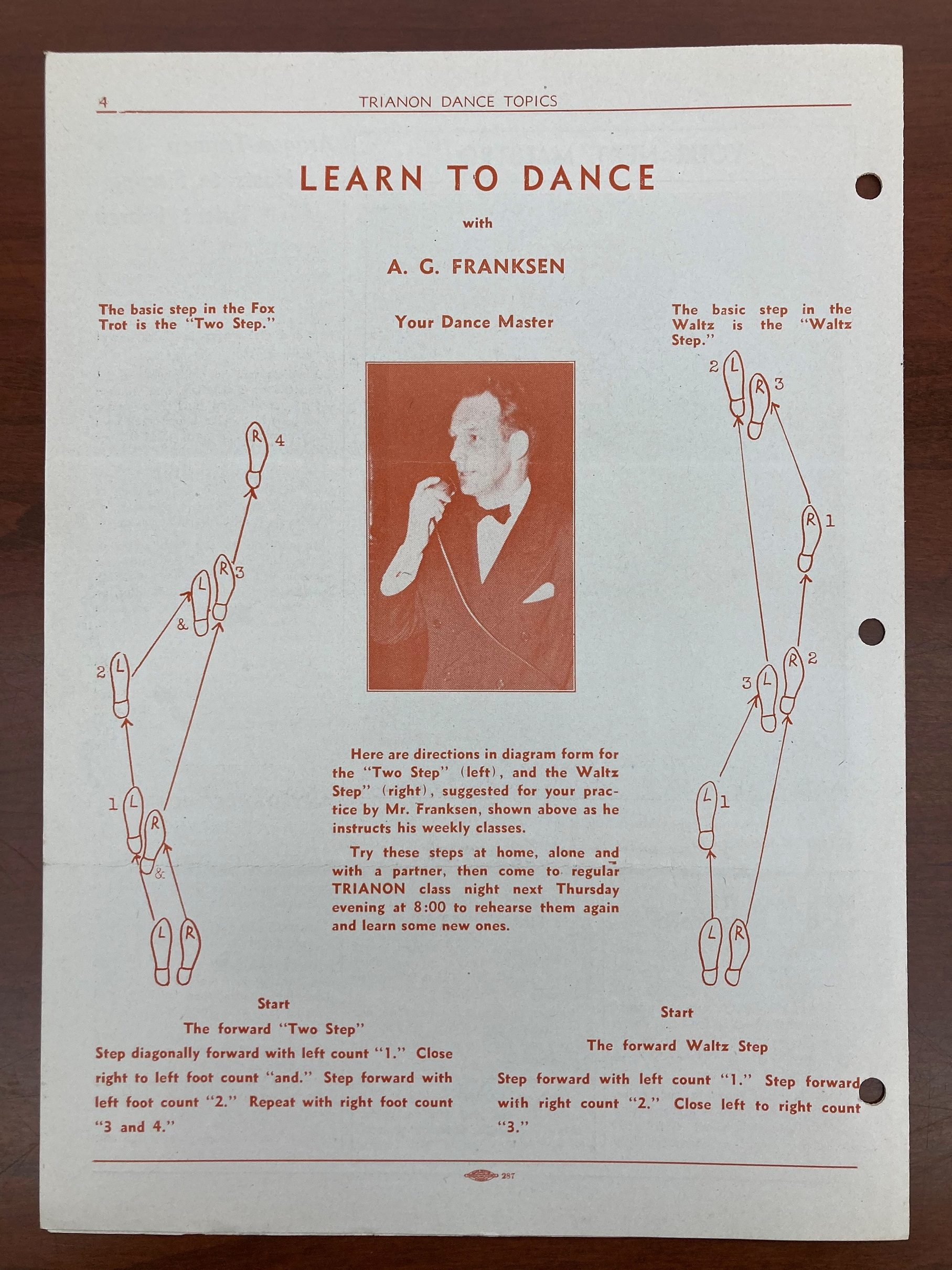

Front and back cover of “Dance Topics, Trianon Ballroom,” featuring Lawrence Welk and the basic steps of the foxtrot, January 14, 1950. Photograph by CHM Staff

Popular as it was, the Trianon was not without its failures, many of which would ultimately lead to its closing in 1958. For one, from the moment the doors opened, the Trianon served a strictly white clientele, which would open the doors for competitors catering to the South Side’s growing Black clientele, a market share that would only grow larger as white flight from the area steadily increased. The declining interest in ballroom dancing certainly didn’t help the once great venue’s ailing status.

Bobby Bland performing at the Trianon Ballroom, 6201 S. Cottage Grove Ave., Chicago, December 7, 1963. CHM, ICHi-138947; Raeburn Flerlage, photographer

After it closed, there was an effort to revive the dance hall under new management and a new name (now going by El Sid), but the rebrand was ultimately doomed to fail. At some point, as evidenced by photographs in the Museum’s collection, the Trianon opened its stage to Black performers and ensembles, but by then, it was far too late. The building that was home to the venue would ultimately be demolished in 1967 to make room for low-income housing.

View of guests attending Queen of Finnie’s Annual Masquerade Ball at the Trianon Ballroom, 1958. Guests in attendance included donor James C. Darby and members of Chicago’s gay community. CHM, ICHi-176136; James C. Darby, photographer

The legacy of the Karzas brothers would continue beyond the Trianon and the Aragon, with Andy Karzas, who became the eventual owner and operator of the Aragon by the early 1960s but would go on to be better remembered for his role as an on-air personality and opera virtuoso for WFMT. He passed away in 2011 at the age of 77.

Additional Resources

- Learn more about Chicago’s history of dance halls in our Encyclopedia of Chicago entry.

- Listen to Andy Karzas discuss both the Aragon and the Trianon in a 1963 interview with Studs Terkel.

- See more of James C. Darby’s photographs in our Google Arts & Culture story Drag in the Windy City

- Read the 1973 Chicago History article “The World’s Most Beautiful Ballrooms”

- Visit the Abakanowicz Research Center to see more photographs and ephemera from the Trianon Ballroom