Latest Posts

NASCAR is hosting its first ever street courses during the 2023 Fourth of July weekend right here in Chicago, inaugurating two separate races, the 100-lap Grand Park 220 and the 55-lap Loop 15. The Windy City is no stranger to automobile competitions. In 1895, the Chicago Times-Herald Race, the nation’s first automotive race, took place in Chicago and changed the course of US history.

Herman H. Kohlsaat, head-and-shoulders portrait, c. 1903. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/00652040/.

The competition was the idea of Herman Henry (H. H.) Kohlsaat, who made his fortune as an entrepreneur in the food industry and a newspaper publisher. Kohlsaat got the idea from a race that ran in 1895 from Paris to Bordeaux. His rationale for hosting one was two-pronged. He believed that travel by horse carriage would soon become a thing of the past due to the rapid pace of technological advancements, and hosting a race was a unique way to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the Chicago Times-Herald, of which he was the proprietor.

The race was originally scheduled to take place on July 4, 1895, to take advantage of the crowds already gathered in the city. However, the date was pushed back when many competitors requested more time to complete their racing machines. As part of the campaign to promote the competition, Kohlsaat held a contest in the Times-Herald asking readers to submit nominations for what they thought the new “self-propelling road carriages” should be called. After receiving many submissions, the newspaper declared “motocycle” the worthiest term, awarding the entrant a prize of $500 ($18,100 in 2023). Kohlsaat ended up rescheduling the Times-Herald Race for Thanksgiving 1895. Up for grabs was a $5,000 pot: $2,000 for first place, $1500 for second, $1000 for third, and $500 for fourth. (In 2023, $72,411 for 1st, $54,308 for 2nd, $36,206 for 3rd, and $18,103 for 4th).

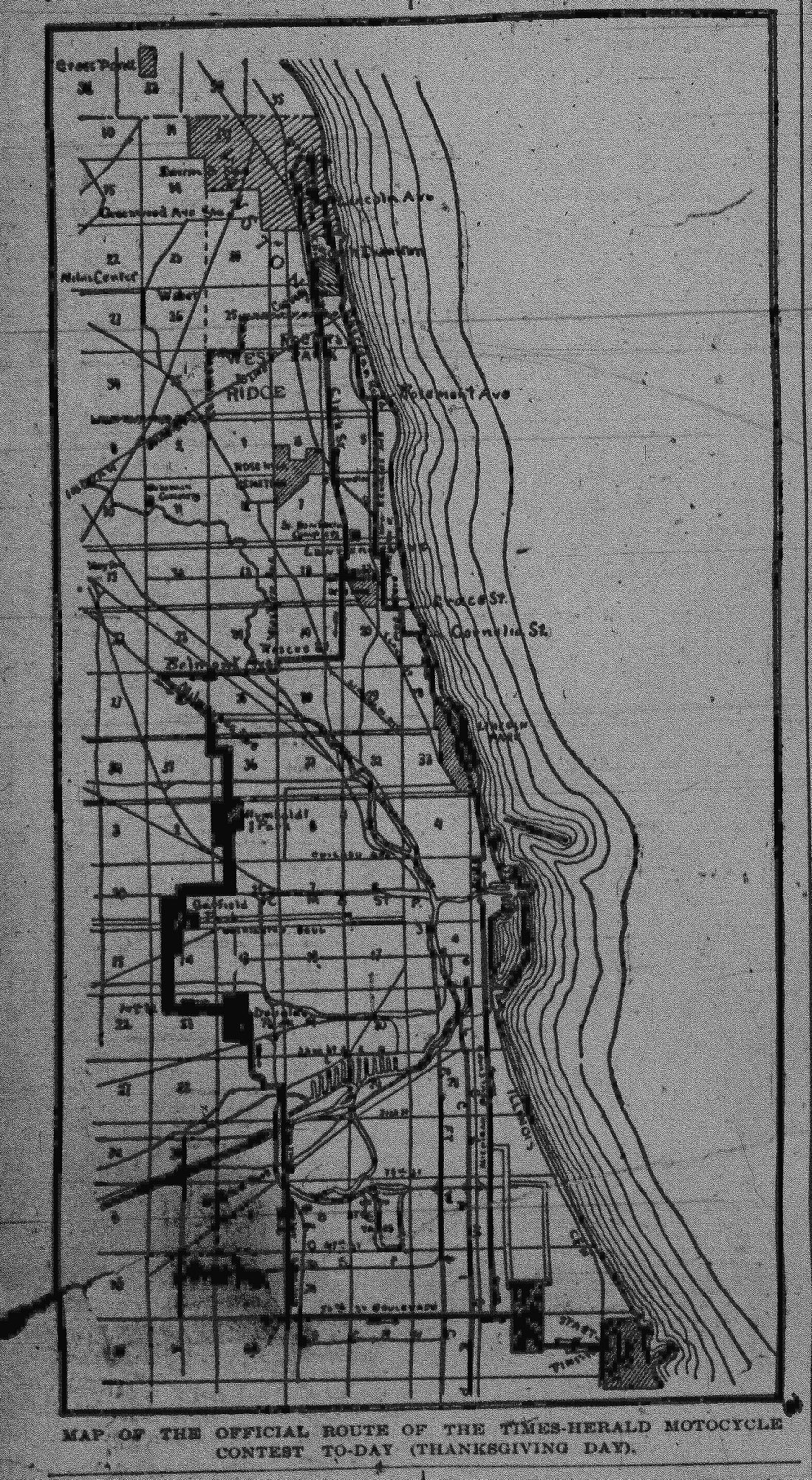

Map of the official route of the Times-Herald motocycle contest, from page 2 of the Chicago Times-Herald, November 28, 1895.

What few accounted for was Chicago weather in November. Initially, 80 competitors registered for the competition, but the night before the race, a snowstorm coated city streets with six inches of snow, which brought down the number of committed racers to eleven. At the morning lineup, only six vehicles made it to the starting line at the Midway Plaisance. While the original race plans had drivers going further north, the blizzard led to a significant modification in the track. Drivers would complete a loop from the city’s South Side to north suburban Evanston and back again. Altogether, the official distance of the race measured just over 50 miles.

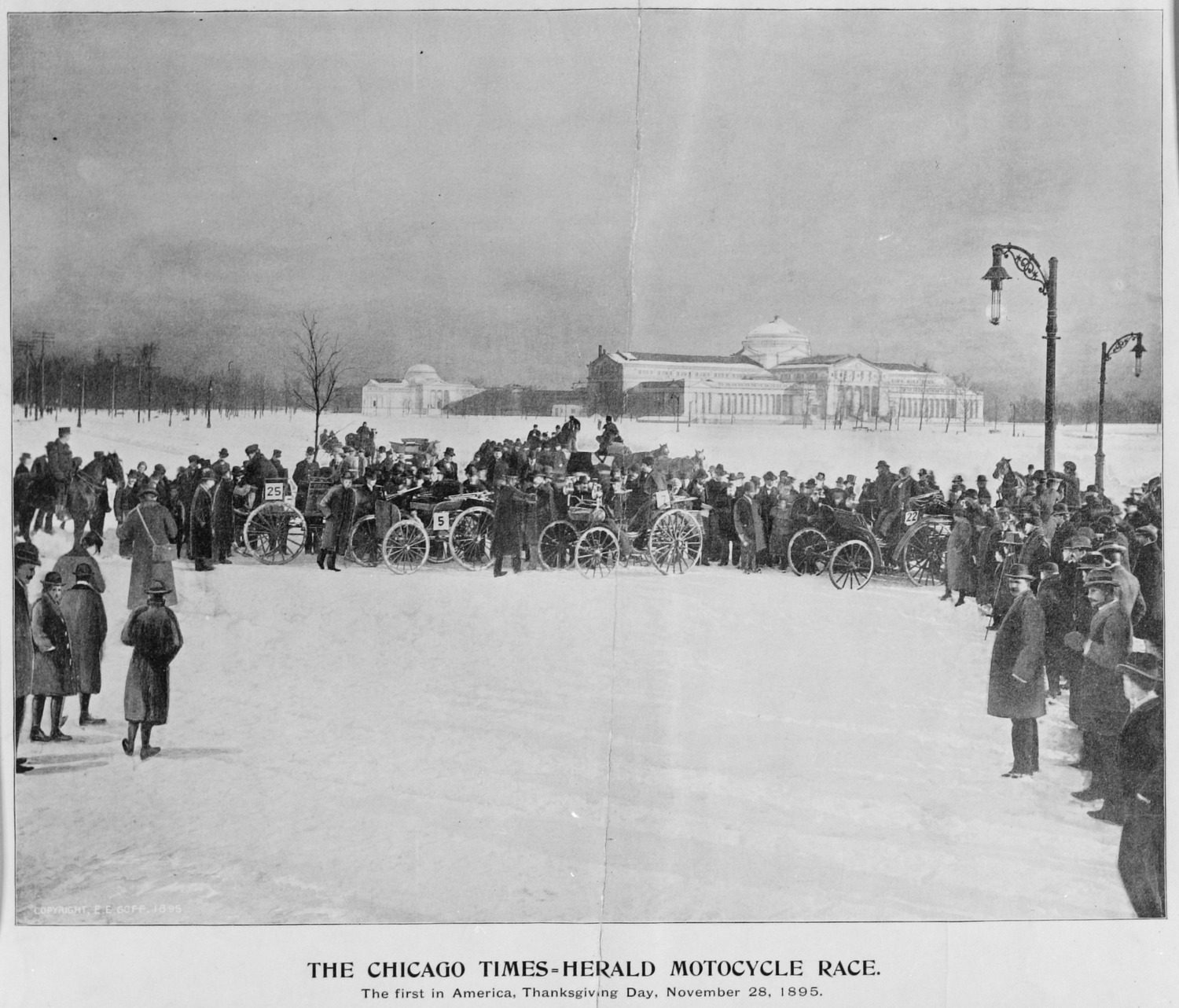

The start of the Chicago Times-Herald motocycle race, the first in the United States, on Thanksgiving Day, November 28. 1895. CHM, ICHi-003646

The six vehicles that lined up at 9:00 a.m. on race day were feats of engineering. Four of the six competitors powered their vehicles with gasoline. Three of the four gasoline vehicles were built by German engineer Karl Benz, the namesake of modern-day Mercedes Benz. One was sponsored by Hieronymus Mueller & Co. from Decatur, Illinois, the second by the De La Vergne Refrigerating Company, and the third by RH, Macy & Co., both of New York. The fourth gasoline-powered vehicle was the Duryea, made by the Duryea Motor Wagon Company based out of Massachusetts. The other two vehicles were electric and participated in the race not as serious contenders but instead to showcase the potential of electric drivetrains. The Morris and Salom Company from Philadelphia sponsored one, dubbed the Electrobat, while the other belonged to Chicagoan Harold Sturges, previously exhibited at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition.

J. Frank Duryea, designer, builder, and driver of the automobile that won the Chicago Times-Herald race, with umpire Arthur W. White, November 28, 1895. CHM, ICHi-009009

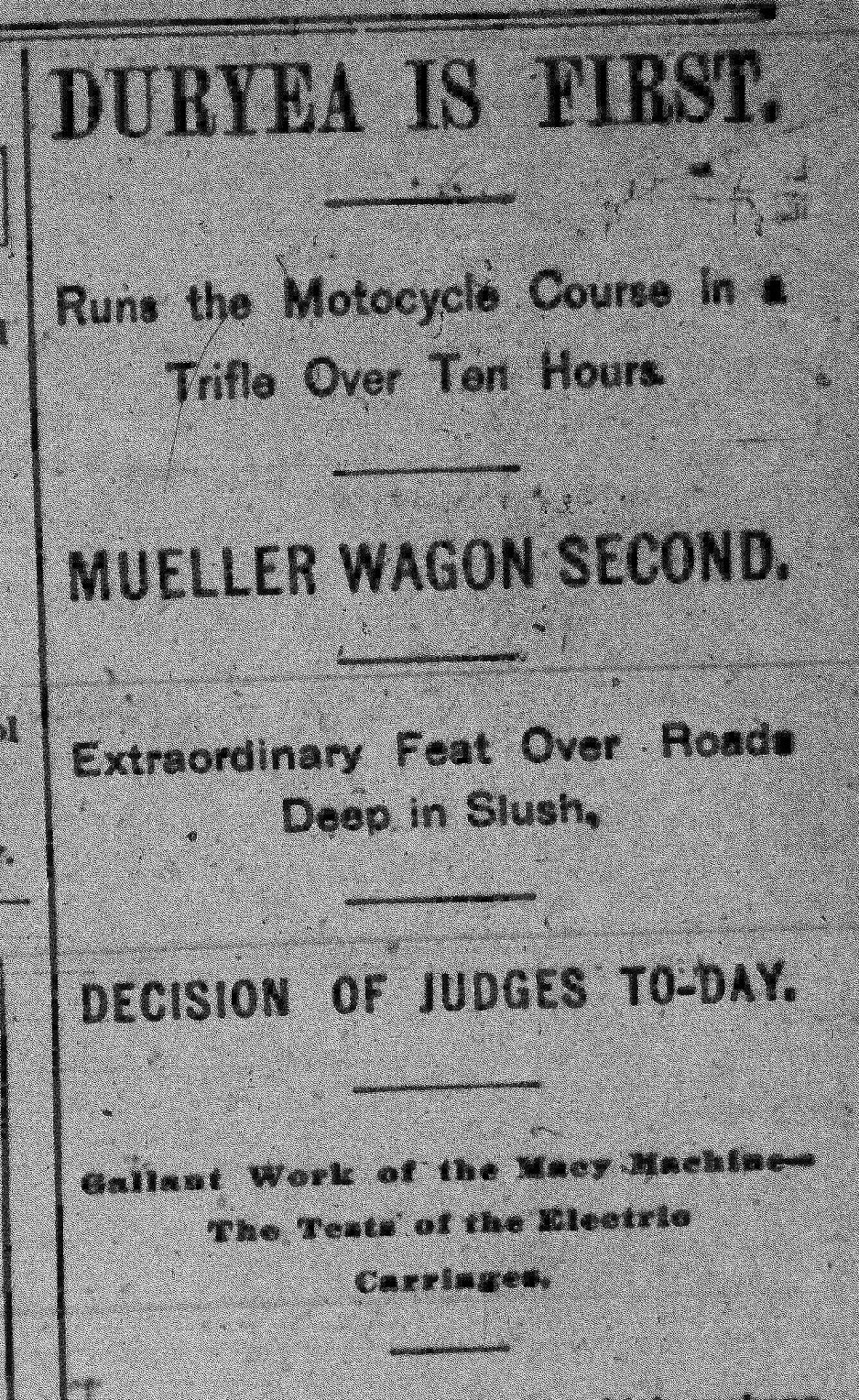

The race was anything but high speed. Thanks to the weather, road conditions, and primitive engineering powering the vehicles, the average speed at which cars traveled the course was a whopping seven miles per hour. Additionally, every competitor needed to make space for a race umpire in their vehicle, who ensured that drivers kept to the course. After many starts, stops, and a breakdown or two, the American-made Duryea was the first to cross the finish line, logging over 10 hours on the road. Second place came to the Mueller Benz from Decatur. These two were the only competitors who completed the race, with the rest dropping out due to damage to their vehicles or equipment malfunctions.

Front page of the Chicago Times-Herald on November 28, 1895, with a recap of the race.

Ultimately, the Times-Herald Race started what would become a revolution. Six years later, the first Chicago Auto Show was organized in 1901 to showcase the reliability and power of the personal vehicle, marking the start of an automotive tradition that has spanned more than a century of automotive development. Chicago also continued its history of motorsports well into the twentieth century. During the 1940s and ’50s, stock car racing made Soldier Field one of the premier venues in the nation for racing aficionados.

Additional Resources

- The Hieronymus Mueller & Co Benz can still be seen today, as it’s on exhibit at the Hieronymus Mueller Museum in Decatur, IL.

- Encyclopedia of Chicago entry on the Chicago Times-Herald Race of 1895.

- Encyclopedia of Chicago entry on the history of motorsports in Chicago.

On June 14, 1949, former Chicago Cub Eddie Waitkus was shot at the Edgewater Beach Hotel by 19-year-old Ruth Ann Steinhagen in what is thought to be one of the first recognized cases of criminal stalking in the United States.

Eddie Waitkus faces Ruth Ann Steinhagen in felony court, Chicago, 1949. ST-17500605-E1, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Edward Stephen Waitkus was born in 1919 to Lithuanian immigrant parents and grew up in Boston, Massachusetts. He attended Boston College, and his professional baseball career began with a semiprofessional team in Maine. Waitkus made his Major League Baseball debut for the Cubs in 1941, but paused his baseball career to serve in World War II, where he participated in the fighting in the Pacific theatre and earned four Bronze Stars.

When Waitkus returned to the Cubs in 1946, the first baseman was a popular player with the media and a solid hitter, with a .304 average. It was that season when then 16-year-old Steinhagen saw him play and became obsessed. She frequently attended Cubs games, and her mother later said he was all she talked about. Waitkus was traded to the Philadelphia Phillies after the 1948 season, which did not quell Steinhagen’s fixation. She later told the felony court, “I kept thinking I will never get him and if I can’t have him nobody else can.”

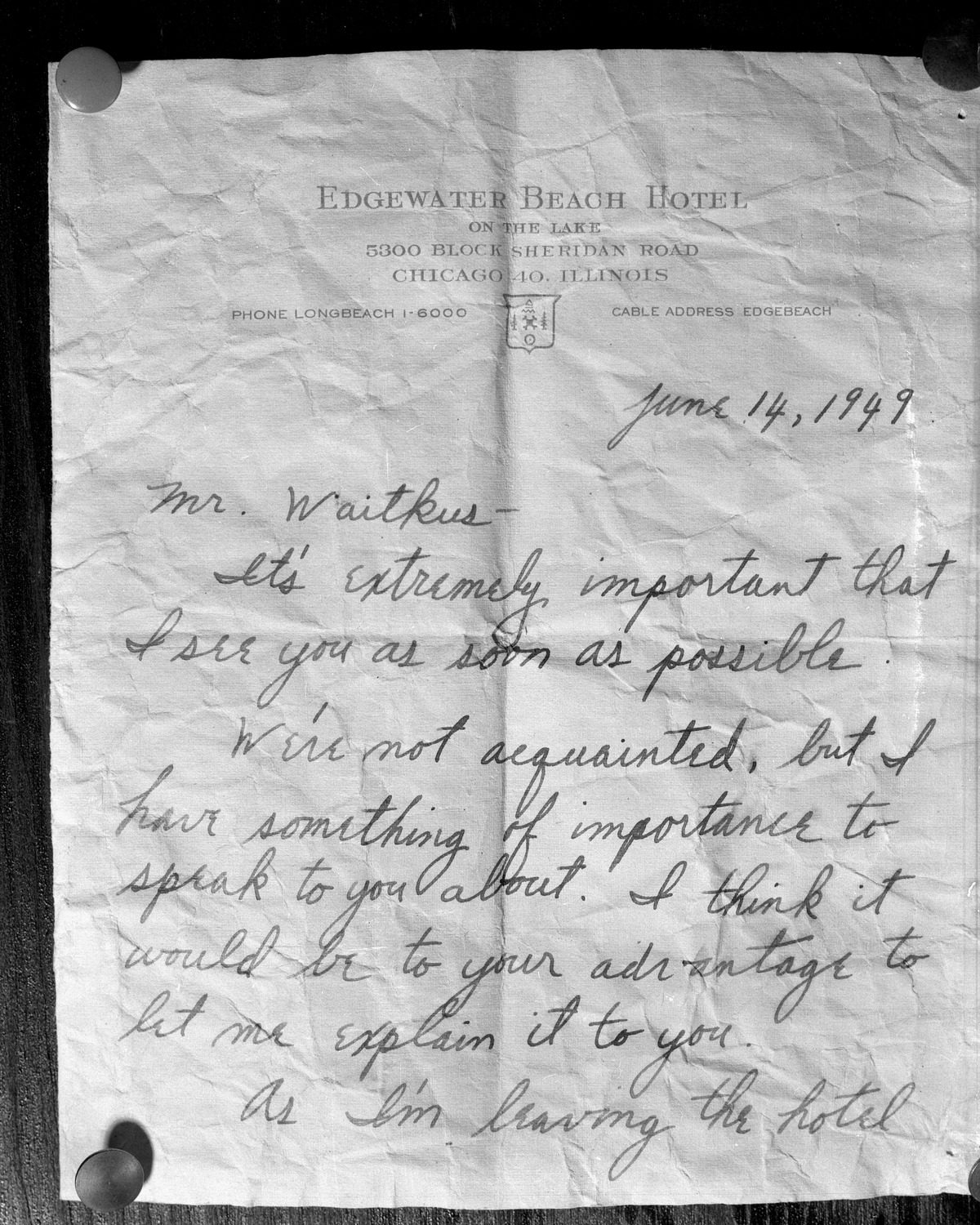

When the Phillies came to town to play the Cubs in June 1949, Steinhagen booked a room for three days in the Edgewater Beach Hotel, where Waitkus and the Phillies were staying. She attended the afternoon game on June 14, in which the Phillies beat the Cubs 9–2 and Waitkus got a hit. Later that night, Steinhagen gave the bellhop $5 and asked him to give Waitkus a note asking to speak with her on “something of importance.”

Letter written from Ruth Ann Steinhagen to Eddie Waitkus on Edgewater Beach Hotel stationary, Chicago, June 15, 1949. ST-17500076-E1, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

When he got to her room, she reportedly said, “For two years you’ve been bothering me and now you’re going to die” and shot him with a .22-caliber rifle. She missed his heart but did hit his lung. She called the desk to report the shooting herself, and Waitkus was taken to the hospital.

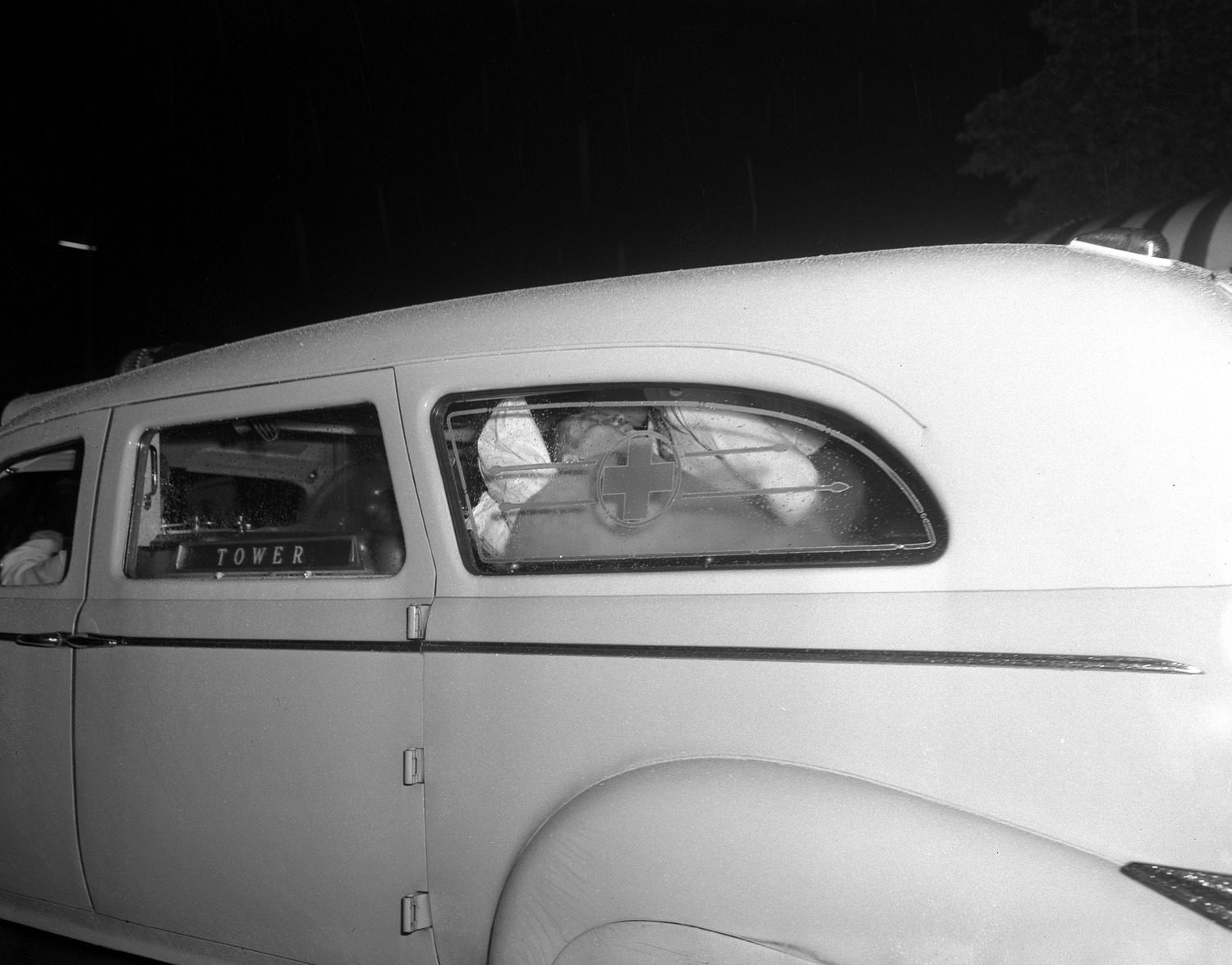

Eddie Waitkus being rushed to Illinois Masonic Hospital in an ambulance after being shot at the Edgewater Beach Hotel, Chicago, June 15, 1949. ST-17500139-E1, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Waitkus underwent several operations to remove the bullet. Remarkably, Waitkus returned to play with the Phillies in 1950, where he was the leadoff hitter for the National League pennant winners. He went onto play through the 1955 season. Waitkus died in 1972 of esophageal cancer at age 53.

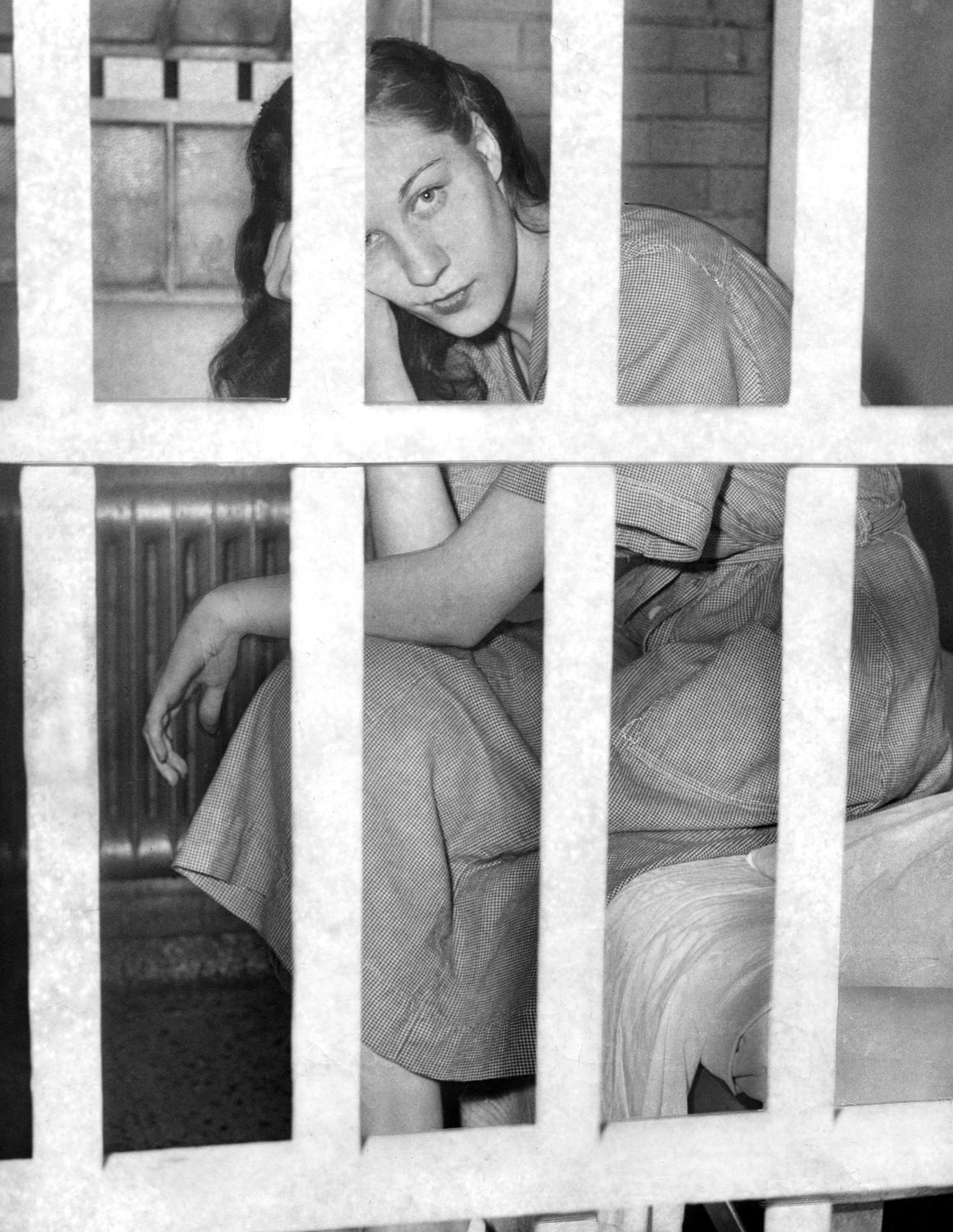

Ruth Ann Steinhagen sitting in Cook County Jail after she shot Eddie Waitkus in the chest at the Edgewater Beach Hotel, Chicago, June 26, 1949. ST-17500604-E1, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Waitkus did not press charges against Steinhagen, but a criminal court judge ruled her to be insane and order her committed to Kankakee State Hospital, where she stayed for nearly three years after the shooting. Further charges were not brought against her, and she lived a reclusive life in Chicago’s Northwest Side, until she died in 2012 at age 83.

What happened to Waitkus is thought to be one of the inspirations for Bernard Malamud, who published his novel The Natural in 1952, which follows the story of a baseball phenom whose career is waylaid after getting shot by a woman. The novel was adapted into a film of the same title, starring Robert Redford, in 1984.

Additional Resources

- See more images from the Chicago Sun-Times collection

To mark the 30th anniversary of the Chicago Bulls’ victory to clinch the 1993 NBA Finals and the team’s first three-peat, CHM editor and content manager Heidi Samuelson recounts the path the Bulls took to accomplish this historic feat.

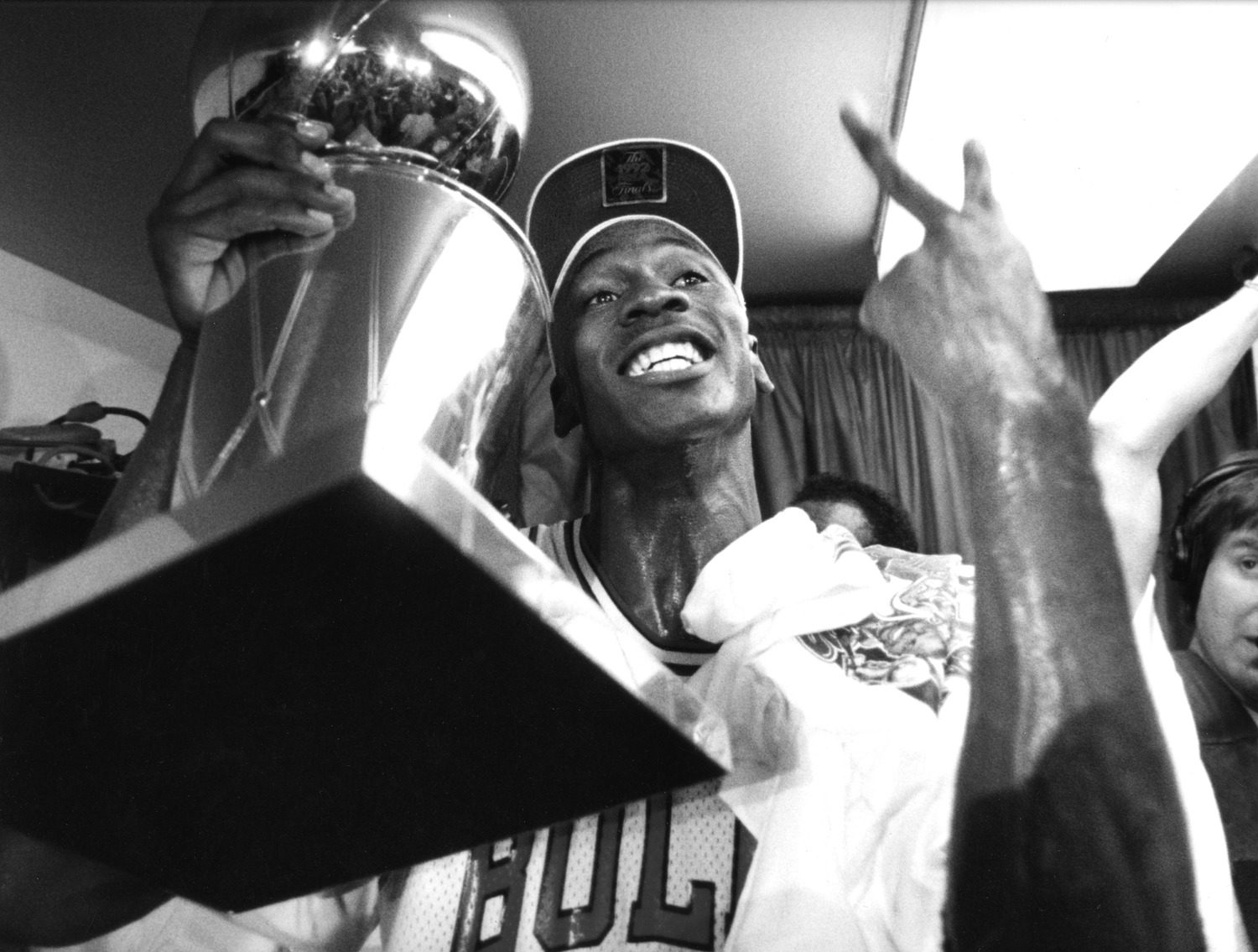

Michael Jordan and Scottie Pippen celebrate winning their third consecutive championship against the Phoenix Suns at American West Arena in Phoenix, June 20, 1993. ST-20000053-0002, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

On June 20, 1993, Chicago Bulls’ point guard John Paxson clinched the team’s third championship in a row with a game-winning three-pointer in Game 6 of the NBA Finals against the Phoenix Suns. It was the first time since the Boston Celtics won eight titles in a row from 1959 to 1966 that an NBA team won three championships in consecutive years.

The Chicago Bulls joined the NBA in 1966 when the league expanded from nine teams to ten. Although they started to see some success in the early 1970s, including four 50-win seasons and reaching the conference finals in 1975, it wasn’t until the late 1980s that the team began to reach new heights.

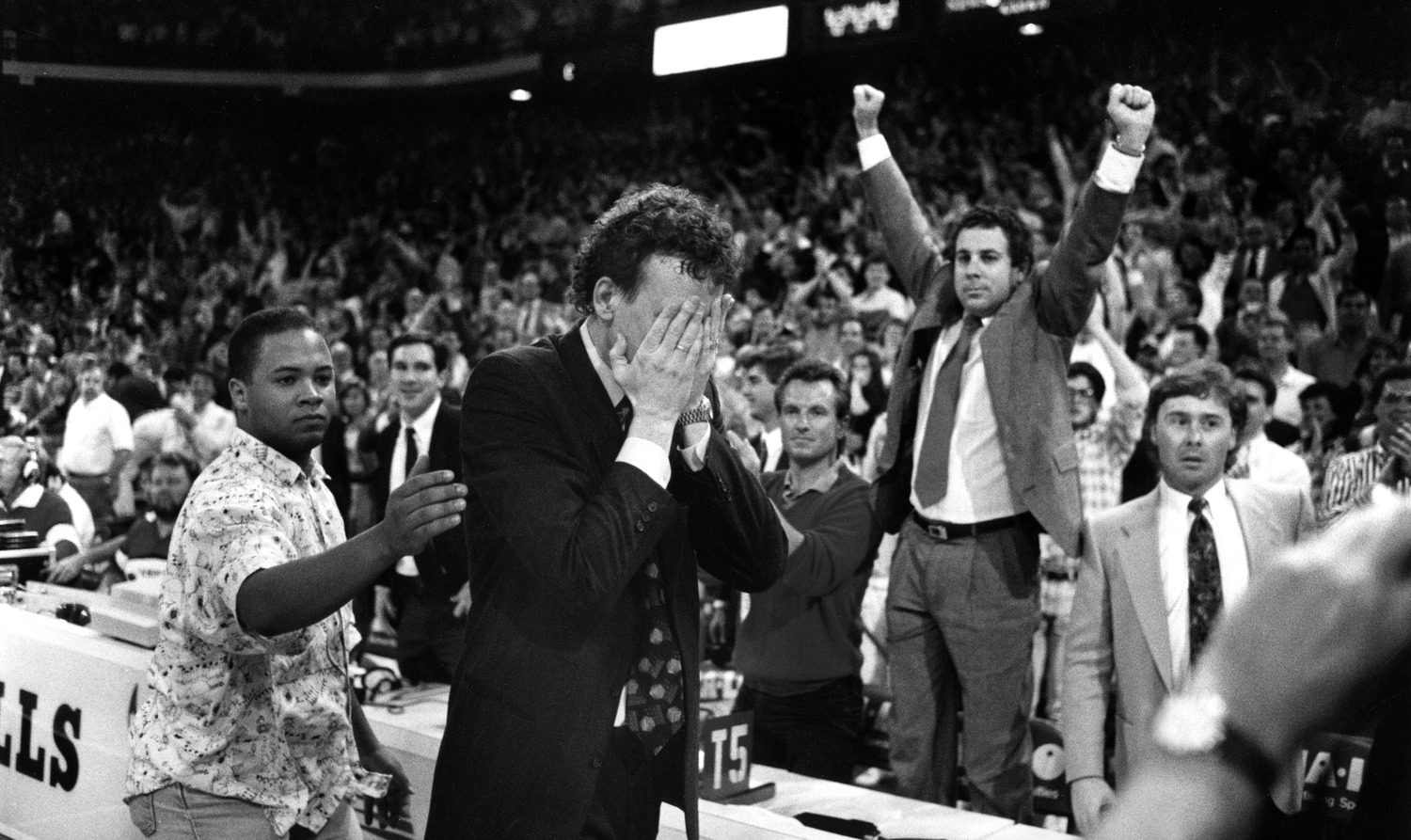

Chicago Bulls coach Doug Collins puts his hands to his face as the Bulls beat the New York Knicks at Chicago Stadium to advance to the Eastern Conference finals, Chicago, May 19, 1989. ST-17500477-E1, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

They had solid players in their starting guard positions with John Paxson and emerging superstar Michael Jordan, who they drafted in 1984. Then, in the 1987 NBA draft, the Bulls acquired forwards Scottie Pippen of the University of Central Arkansas and Horace Grant of Clemson University. The following year, they traded for veteran center Bill Cartwright. The final piece of the puzzle was coach Phil Jackson. Together, Jackson and this starting lineup, along with sometimes-starter B. J. Armstrong, and a bench that included Craig Hodges, Stacey King, Will Perdue, and Scott Williams, won three championships in a row from 1991 to 1993.

Benny the Bull during Game 2 of the 1991 NBA Finals at Chicago Stadium, Chicago, June 5, 1991. ST-50004141-0086, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

In 1991, the Bulls won 61 games, then a franchise record. In the playoffs, they bested their Eastern Conference rivals the Detroit Pistons in the conference finals 4‒0 to face the Los Angeles Lakers for the championship. The Lakers were led by three-time league MVP Magic Johnson, but the Bulls had home court advantage. They won in a decisive 4‒1 series. Jordan was named the Finals MVP, averaging 31.2 points on 55.8% shooting and 11.4 assists.

Horace Grant goes up against Lakers’ Vlade Divac during Game 2 of the NBA Finals at Chicago Stadium, Chicago, June 5, 1991. ST-50004141-0023, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

The Bulls continued their dominance the next year, finishing the regular season with a 67–15 record. Their first real test in the playoffs came in the Eastern Conference semifinals against the New York Knicks, who took the series to seven games. The Bulls were victorious over the Cleveland Cavaliers in the Eastern Conference finals, and then faced the Portland Trailblazers, led by future Hall of Famer Clyde Drexler, for the championship. On June 14, the Bulls won in Game 6 to a home audience at Chicago Stadium.

Michael Jordan holds the Bulls’ second NBA Championship trophy at Chicago Stadium, June 14, 1992. ST-17500544-E1, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

That year the Chicago Blackhawks were in the NHL Finals, also being played at Chicago Stadium and potentially causing a schedule conflict. But it was not meant to be, as the Blackhawks lost the series 4–0 on June 1.

B. J. Armstrong guards the Suns’ Kevin Johnson during NBA Finals Game 2 in Phoenix. Scottie Pippen and Charles Barkley appear in the background, June 11, 1998. ST-10000029_0012, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Coming off Jordan and Pippen playing for the 1992 Olympic Dream Team that summer, the Bulls had a solid 57–25 season, good enough for second place in the Eastern Conference. The Bulls swept their opponents in the first two rounds of the 1993 playoffs, facing the no. 1 seeded Knicks in the Eastern Conference finals. After a victorious 4–2 series, they faced the Phoenix Suns in the NBA Finals.

Newborns wearing red hats in a hospital nursery decorated in support of Chicago Bulls in the 1993 NBA Finals, Chicago, June 16, 1993. ST-30002508-0032, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

The Suns were led by all-star point guard Kevin Johnson and future Hall of Famer and fellow Dream Team member Charles Barkley, who the Suns traded for in the 1992 offseason. The Bulls won the first two games on the road and then traded victories with Suns up to Game 6. Jordan averaged a record 41.0 points during the Finals and won the Finals MVP for the third straight year.

Chicago Bulls fans parade the streets of Chicago in response to the sixth NBA championship game against the Phoenix Suns, near Chicago Stadium, 1901 West Madison St., June 20, 1993. ST-19041163-0099, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Additional Resources

- Bulls’ publications and ephemera including Chicago Bulls media guides and yearbooks and BULLpen game programs can be found at the Abakanowicz Research Center, which is free to visit.

- CHM Images has a large collection of Chicago Bulls images from the Chicago Sun-Times collection, dating back to 1966.

- The Museum’s Chicago: Crossroads of America exhibition has Bulls items on display in the My Kind of Town section.

June is graduation season! In this blog post, Abakanowicz Research Center page Brigid Crawley highlights the Chicago History Museum’s collection of yearbooks, which spans from 1858 to 2012.

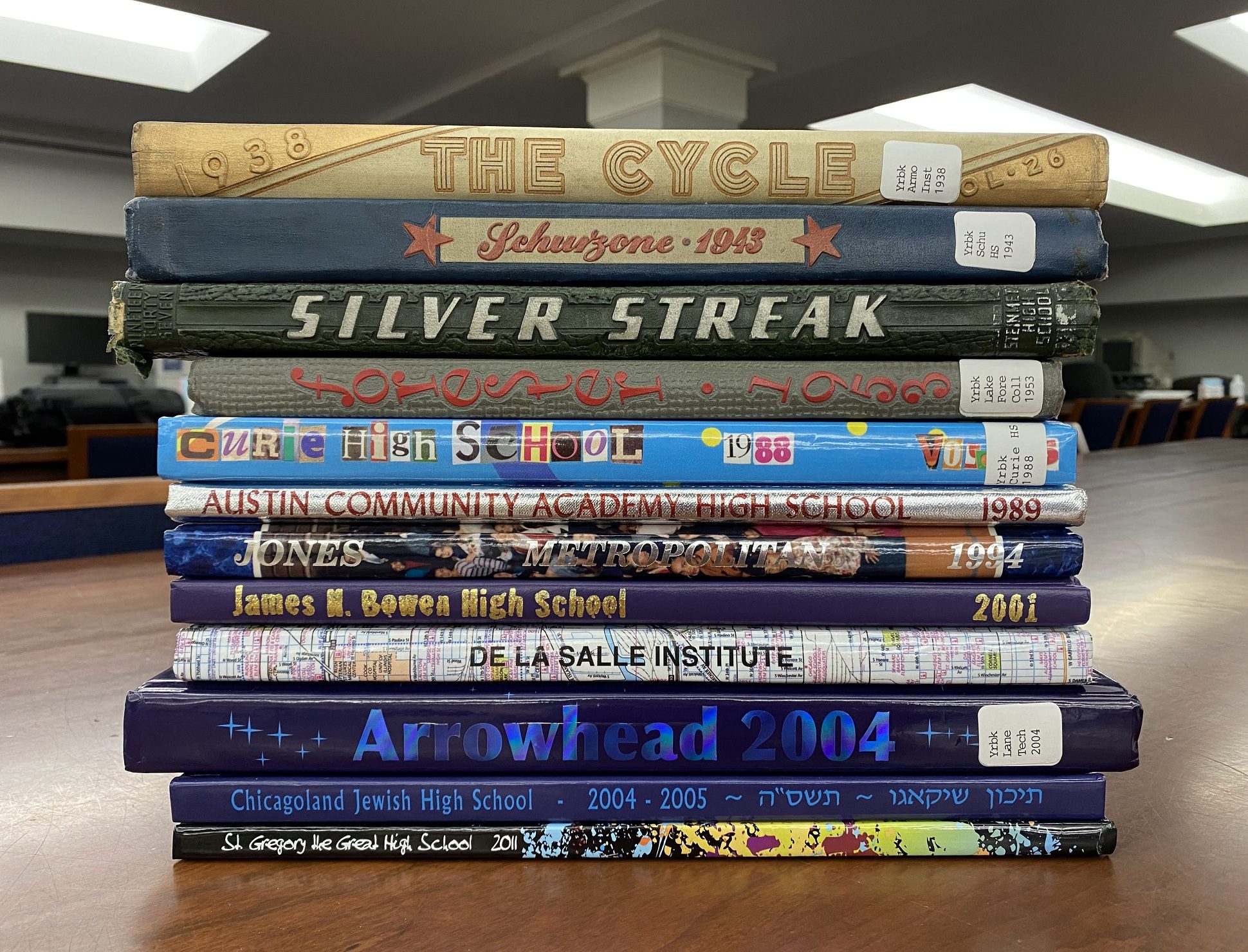

A stack of yearbooks ranging from 1938 to 2011. All photograph by CHM staff

While yearbooks often evoke a feeling of nostalgia, they are also frequently used by researchers to find an individual or as a resource for subject study. The new Yearbook Collection LibGuide has suggestions for subject areas, tips for navigating publication schedules, and a breakdown of expectations by timespan to help guide researchers through our collection and explore these materials in new ways.

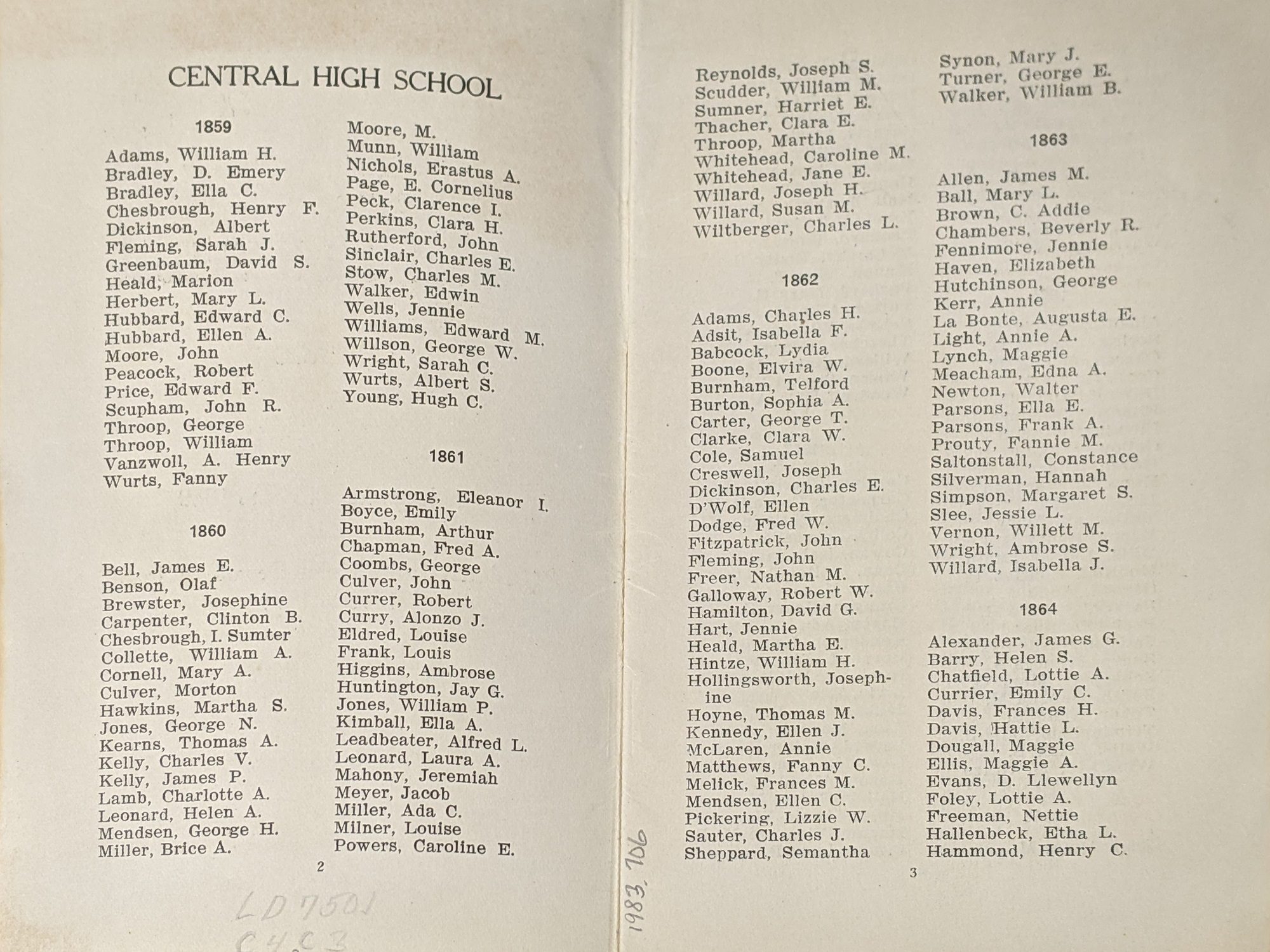

Yearbooks have not always looked or functioned the way they do today. In the late 19th century, secondary and higher education were not as common. Early yearbooks were often intended for the public to inform a broad audience about the credentials of the teachers or professors, the quality of the instruction, the students’ daily life, and, for those colleges or universities outside of Chicago, the surrounding environment and region. Schools, colleges, and universities used yearbooks to highlight the institution’s achievements.

Central High School, 1909. Some early yearbooks were published after graduation and included lists of student names from earlier years.

In the early 20th century, yearbooks transitioned into a keepsake for students. Dedication pages addressed fellow students instead of a public audience. Yearbooks were a curated record of individual and collective experiences. Students and editors experimented with how to capture their accomplishments and aspirations through creative writing, graphic design and photography, and editorial design choices.

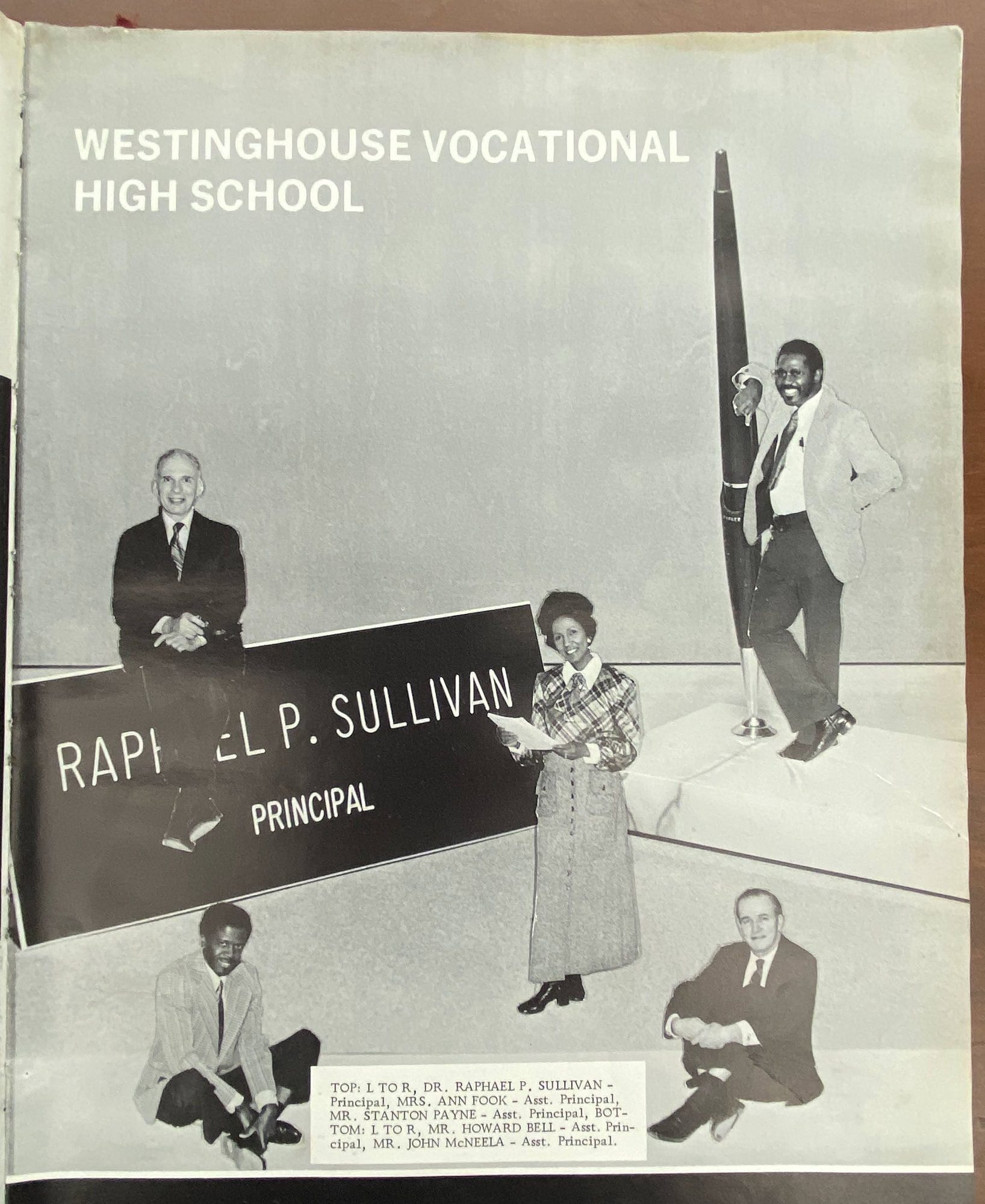

Westinghouse Vocational High School, 1973. Since printing photographs in yearbooks became feasible, photo collages and montages have remained popular with students.

Some yearbooks are filled with different types of written expression, such as editorial pieces, excerpts from correspondence, or jokes and sketch dialogues. Other yearbooks experiment with collage techniques or documentary-style photographs that capture feelings and environments visually.

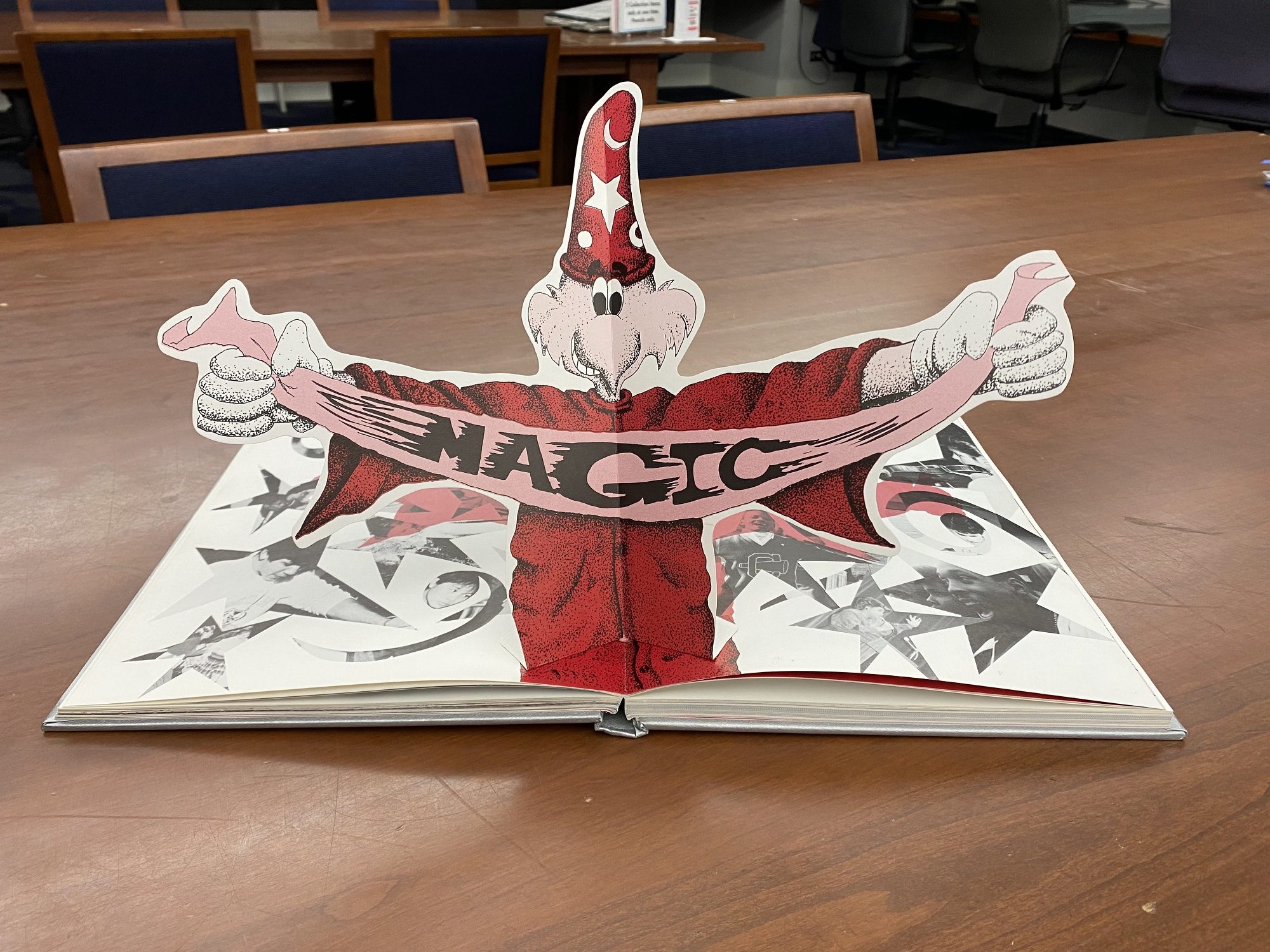

Marie Sklodowska Curie Metropolitan High School, 1987. This yearbook has a pop-up condor (the school mascot) dressed as a wizard since the yearbook’s theme was “Magic.”

Predicting what content researchers will find in yearbooks and what types of photographs will be included is difficult. Yearbook design varied between institutions based on size, the intent of the publication, and the staff, time, and resources available to document the year’s events. In our collection, college and university publications tend to have a formal tone compared to high schools of the same period; think of more caps and gowns and fewer baby photographs. It is the unknown element that makes searching through the yearbooks so exciting.

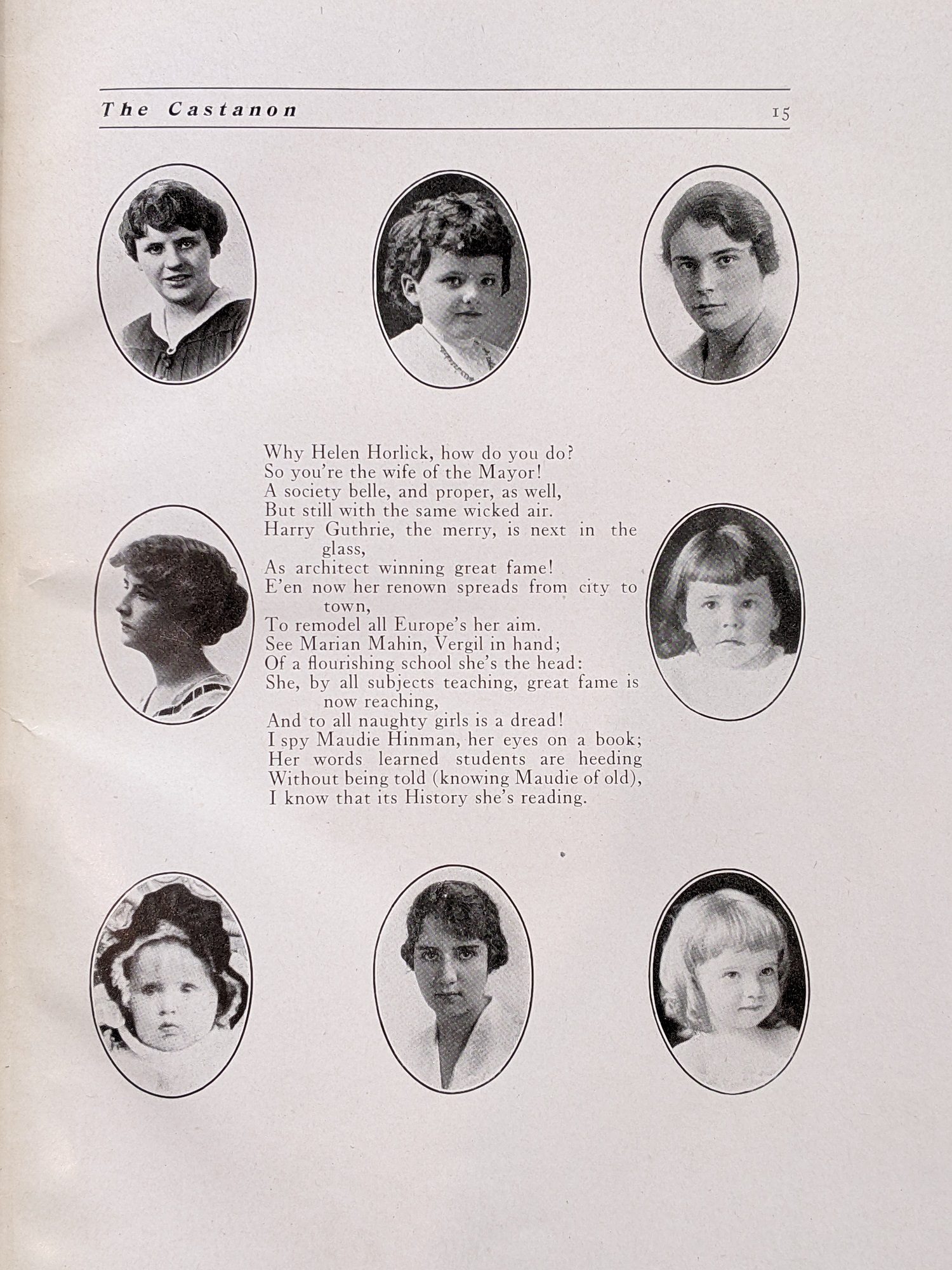

University School for Girls, 1917. Yearbook editors included baby photographs and used poetry to identify graduates.

As a resource, yearbooks provide incredible insight into student perspectives about current events. In this way, yearbooks are a primary document, capturing school and community history and significant social changes as they happen. Some of the most exciting finds are how students documented and reflected upon important events, such as the impact of world wars, antiwar strikes, protests about school curriculum, or the opening of a new CTA line. From global events to neighborhood history, yearbooks tell stories from the viewpoint of those that lived it while also including their hopes for the future. These special collections can add a new perspective to historical research.

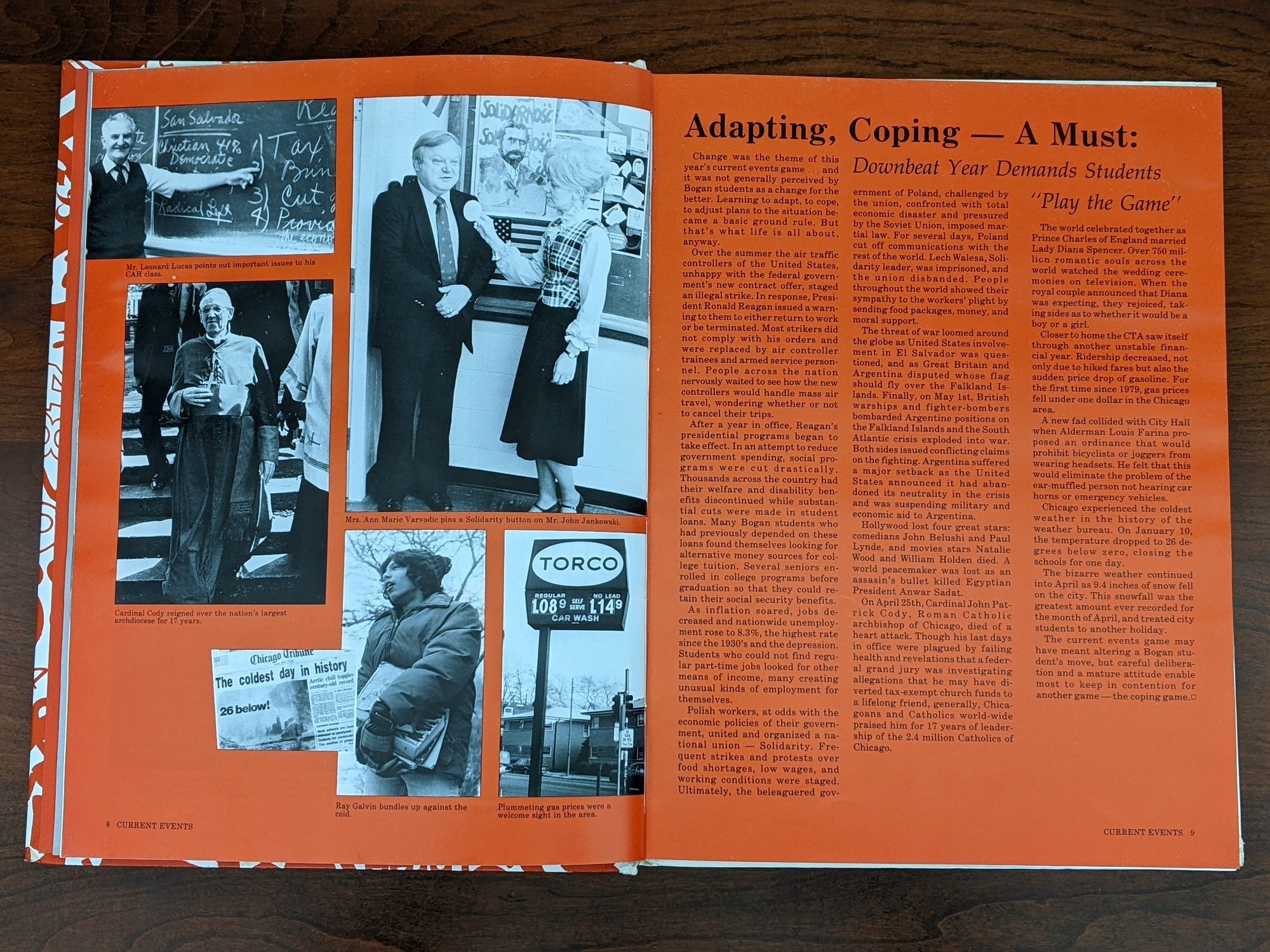

William J. Bogan High, 1982. Students reflect on how current events impact their lives.

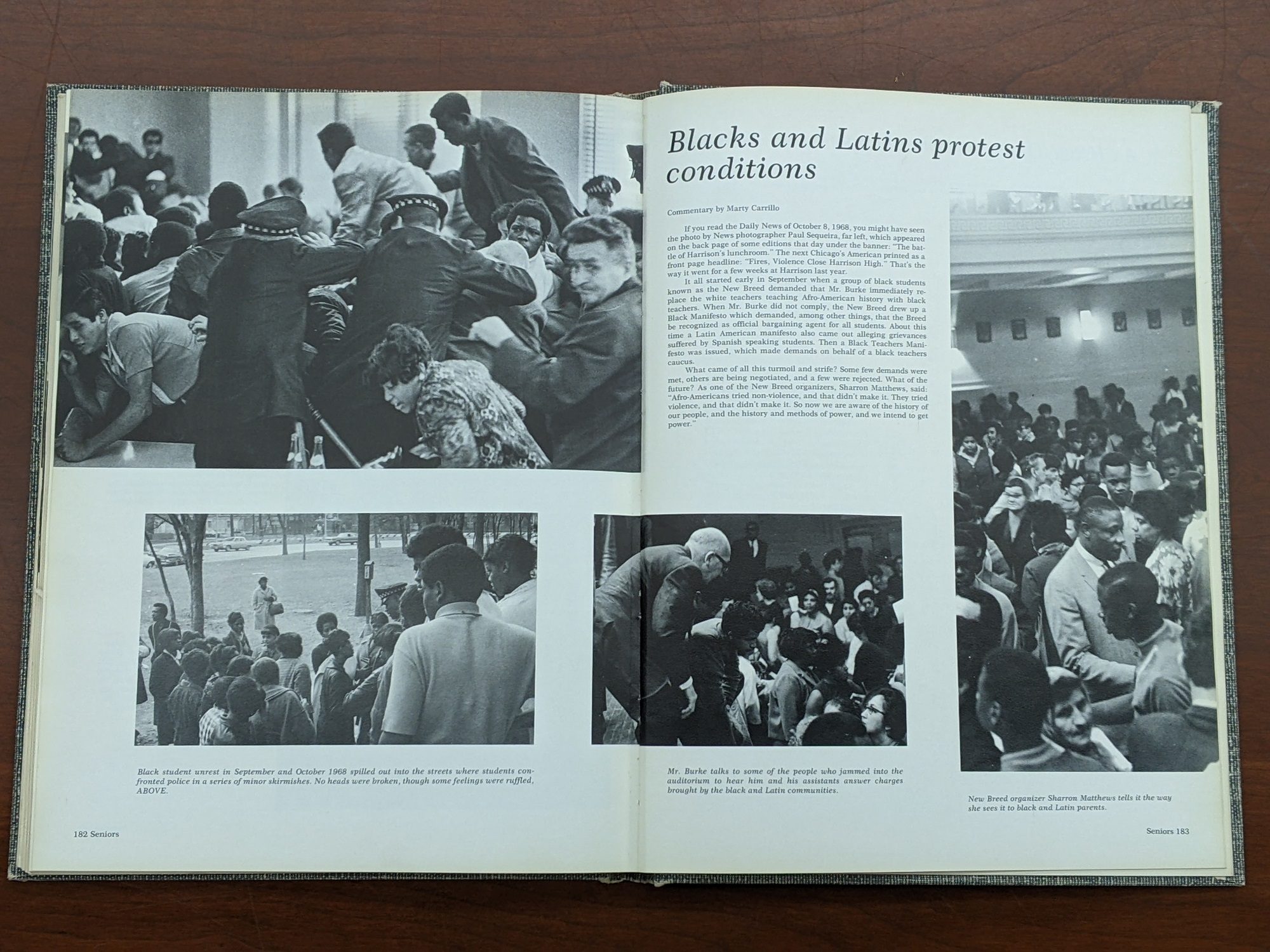

Carter H. Harrison High, 1969. As the yearbook text mentions, some of these events are covered in the news, but student points of view are an integral part of history.

The finding aid for the yearbook collection includes a list of institution names and years of publications. You can also search in ARCHIE, our online catalog, and consult the Yearbook Collection LibGuide for information on How To Search.

Want to donate a yearbook? Check the LibGuide for more information and to learn about our collecting scope and criteria.

Additional Resources

- Listen to Studs Terkel’s interview with St. Timothy Catholic School students ranging from ages 13–17

- Read the Fall 2004 issue of Chicago History magazine, which explores teenage life across the 20th century

- Visit the Abakanowicz Research Center to see CHM’s yearbook collection in person

Algae Guzman is a graduate student at University of Illinois Chicago who has been interning with CHM curator of civic engagement and social justice Elena Gonzales for our upcoming exhibition Aquí en Chicago. Part of their work includes researching Latino/a/x histories of Chicago.

On May 27, 2021, Jesús “Chuy” Negrete passed away at the age of 72 in Chicago. Negrete was born in San Luis Potosí, Mexico. Early in life, he and his family immigrated to the United States in search of work, briefly settling in the Rio Grande Valley in south Texas, where I grew up. This particular region was known as el valle magico, the Magic Valley, due to its fertile soil and high production of citrus and other crops. By the time Negrete was seven years old, his family had resettled in South Chicago where his parents found other employment opportunities.

Throughout his life, Negrete drew inspiration from the Civil Rights Movement, was highly involved in the Chicano Movement, and fought for laborers’ rights. His most powerful form of protest was through songs called corridos. Corridos are a genre of Mexican folk music, and their form is a mechanism for storytelling. Corridos are most popularly used to tell stories of oppression, immigration, romance, and/or life histories. Negrete honed his songwriting skills to tell the stories of Latino/a/x individuals from inside and outside of Chicago.

Negrete on stage with guitar during a Teatro del Barrio performance, Chicago, c. 1970. Photograph by Louis Guadarrama Jr. Image courtesy of the Southeast Chicago Historical Society and Museum, 1993-017-20.

When deciding what my research contribution would be for the upcoming Aquí en Chicago exhibition, I strategically tried to find a topic that would support the research needed to complete my master’s thesis at the University of Illinois Chicago. In a surprising turn of events, my research on Negrete helped me find other talented Tejano and Conjunto musicians who crafted and performed corridos. Most of them rose to fame with origins in the Valley, such as Narciso Martínez, Lydia Mendoza, Chelo Silva, and Valerio Longoria.

Martínez immigrated to the United States as an infant from Reynosa, Tamaulipas, Mexico, and is most commonly known as the father of conjunto music—another musical genre that at times uses the lyrical structure of corridos alongside instruments like the bajo sexto (sixth bass guitar) and the acordeón (accordion). Mendoza, while born in Houston, Texas, migrated to and from Mexico with her family accompanying her railroad worker father. Silva, born in the lower Rio Grande Valley, went so far as to achieve international recognition in Mexico and South America. Longoria learned how to play the accordion by watching Martínez during breaks while employed in farm work together, then spent years in Chicago touring solo. These musicians, unlike Negrete, did not concentrate on lyrical production that highlighted local or national issues.

Walkout at Republic Windows and Doors in Goose Island, as former employees picket the entrance due to not getting pension, vacation pay, and extended health care after the company closed without proper notification, December 8, 2008. STM-011368057, Tom Cruze/Chicago Sun-Times

In 2009, Negrete wrote and performed two songs, “For the People” and “Huelga,” for a radio documentary, Sí Se Puede, which told the story of Republic Windows and Doors and how the company abruptly closed in 2008, leaving its workers without health insurance, paychecks for hours worked, or jobs.

For the People

And so it came to be that on the fifth of December, one cold day

In the city of Chicago

At the Republic Window Company, they did say

Out on strike that fine ay

And they took over the factory

For those six long days

The people, the workers of the U.E., today

Huelga, huelga, huelga,

Huelga it means strike

Huelga, huelga, huelga,

Huelga, we had just begun to fight

Huelga

El corrido del U.E. strike

El día cinco de diciembre

Allá en la ciudad Chicago

Comenzaron su huelga

Y por seis días enteros

Los trabajadores agarraron la compañía

Era la República compañía de ventanas popular

Era la República ese día en Chicago no muy cerquita del mar

These two corridos told the story of how the workers formed a union and held a strike to combat the injustices they faced. Negrete also wrote songs like “Corrido del bracero,” detailing Mexican immigrants’ struggles in finding work in the United States and the difficult lives bracero workers faced.

Other Chicago residents have taken up guitars and penned their own corridos of events that are occurring around the city. Two brothers, Ignacio and Santiago Echevarría, known as “Los Dos de Michoacán” (The two from Michoacán), wrote two songs, “La emboscada” (The ambush) and “Corrido de Elvira Arellano,” about an undocumented mother who fled deportation and sought sanctuary in a church near Humboldt Park.

While Negrete and the Echevarría brothers used corridos to share the stories of their community, the US government has recently manipulated the musical genre. By creating their own corridos, the US government hoped to discourage migration into the US by telling stories of the dangers of migration in grueling ways. By dispersing these horrific migra corridos through Central American, Mexican, and US radio shows, the aim is to frighten potential migrants from ever making the journey. These songs are small forms of propaganda and part of a covert series of policies put in place to reduce the number of immigrants arriving in the country, otherwise known as prevention through deterrence.

Though the above corridos focus on heavy topics, not all do. Around 1924, a corrido was written about a tax law passed in Chicago that applied only to women with short hair.

Contribución a las pelonas

Atención pongan, señores,

de lo que la prensa ha hablado

en motivo de un decreto

que Chicago se ha implantado.

La mujer que esté pelona

pagará contribución

Mexicana o extranjera

sin ninguna distinción.

Tax on Bobbed Women

Attention, gentlemen,

The press is full of news

Because of a law decreed

In the city of Chicago.

All women with bobbed hair

Will pay a tax,

Mexican or foreigner

Without distinction.

Miss Betty Quick, Miss Elizabeth Carpenter, and Miss Polly Carpenter standing outside near a fence covered in plants, picking flowers, in Chicago, 1920. The Carpenters on the right have bobbed haircuts whereas Quick on the left has her hair in an updo. DN-0072316, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

Humor need not be absent from this genre; in fact, Negrete mastered the balancing act of embedding it into his act. When performing at the 2012 National Association for Chicana and Chicano Studies Conference, he opened with a joke. He recounted a story of someone telling him of the founding of the United States, starting at Plymouth and the thirteen colonies, stating George Washington was Negrete’s father. In response, Negrete stated, “I was reluctant to believe her, and so suddenly I raised my mano on the 16th of September and I told her if George Washington was my father, then why wasn’t he Chicano. . .” before launching into his corrido.

Chuy dedicated his musical career to uplifting stories that often went unheard. Negrete’s lyrical and performance intentionality can also be seen below in his corrido eulogy to Rudy Lozano.

Remembering Rudy Lozano

Spoken word:

. . . Rudy used to say

If you want to live forever

You can never live at all

It is only when you’ve accepted the fact that

you must die,

That you can truly life

Es mejor vivir de pie (It is better to live on your feet)

Que seguir viviendo de rodillas… (Than it is to keep living on your knees)

Singing:

. . . ¿Qué se cayó (What fell)

El ocho de junio? (The eighth of June?)

El compañero asesinado. (The assassinated friend.)

El compañero mexicano. (My Mexican friend.)

El compañero Rudy Lozano. (My friend Rudy Lozano.)

Rudy Lozano listens during a meeting at CASA (the Centro de Accion Social Autonomo, or the Center for Autonomous Social Action), Chicago, February 12, 1975. ST-40001425-0007, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

I find it fitting to end this article with a mention of the tocayo (namesake) high school responsible for the forthcoming Aquí en Chicago exhibition, the Rudy Lozano Instituto Justice and Leadership Academy. Through song and education, we can keep both these Mexicano Chicagoans alive.

Katherine Quiroa is a graduate student at University of Illinois Chicago who interned with CHM curator of civic engagement and social justice Elena Gonzales for our upcoming exhibition Aquí en Chicago. Part of her work includes researching Latino/a/x histories of Chicago.

During the late 1910s, the Mexican population was growing in Chicago. The majority of Mexicans lived on the Near West Side, which is now home to neighborhoods like University Village, Little Italy, and Greektown. A century ago, the Near West Side, known as “the Valley,” was home to immigrants of predominantly Greek, Italian, and Jewish heritage who established themselves in the area in the nineteenth century. The Near West Side was also home to many African Americans who arrived in the 1930s. In 1917, this community continued to diversify as Mexicans, who migrated to the US as a result of World War I and the Mexican Revolution, settled on the Near West Side.

Settlement houses began developing in areas such as Chicago where urbanization, industrialization, and immigration were on the rise. In 1889, Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr founded the Hull-House social settlement. They envisioned a space where social services, entertainment, education, and more would aid the low-income immigrant population to establish roots in Chicago. By 1917, anchored by Hull-House, the Near West Side was home to Chicago’s first Mexican barrio on the intersections of Harrison and Halsted streets; the neighborhood was home to more than 7,000 Mexicans. Mexican immigrants who arrived after the war made use of the services and amenities Hull-House provided, easing their adjustment to Chicago.

Exterior of the Hull House after its relocation to the University of Illinois Circle campus and four-year remodeling and restoration project, 800 South Halsted Street, Chicago, June 2, 1967. ST-13001698-0002, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Although the Near West Side was a low-income neighborhood, residents had created a vibrant, diverse, and well-established community. From 1949 to 1961, the city was constructing the Eisenhower Expressway in hopes of easing traffic while simultaneously redeveloping impoverished residential neighborhoods like Near West Side which displaced many residents who were either pushed out by construction or could not afford to live in the area. The highway displaced roughly “13,000 people and forced out more than 400 businesses in Chicago alone.”

At the same time, the University of Illinois Chicago campus on Navy Pier became congested by an overwhelming number of students who eventually protested for their campus to be relocated. Mayor Daley discreetly proposed that the Harrison-Halsted site be the new location for the University of Illinois Chicago Circle (UICC) campus which had been accepted by the University Board. The site was convenient for urban developers and officials as the land had been declared a site for urban renewal. Many Chicagoans heavily criticized the Department of Urban Renewal for failing to keep their word to the Near West Side residents when they claimed they “would improve the community, and the first priority would be the residents.”

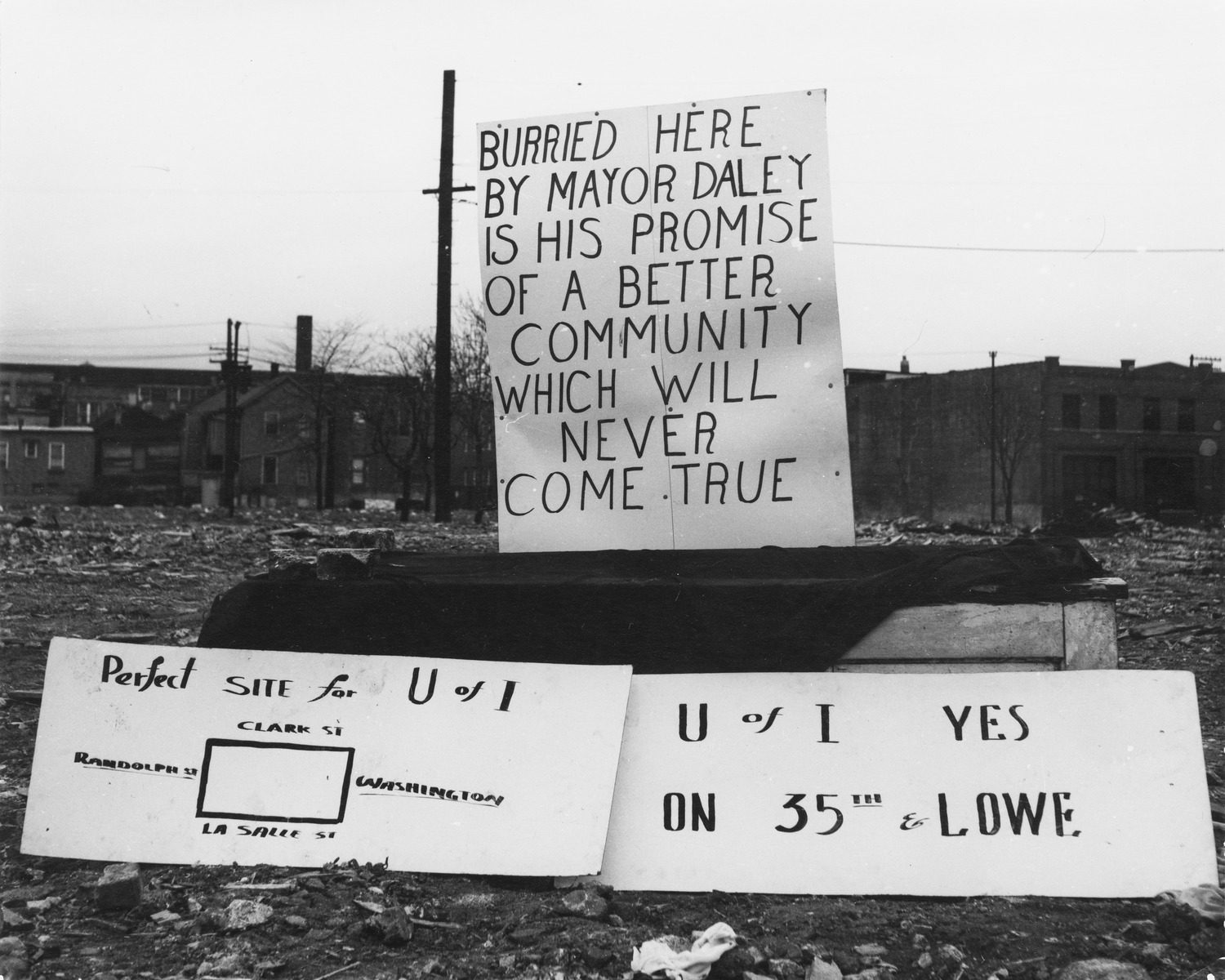

Vacant property (razed for future building) and signs in Harrison and Halsted Streets area, Chicago, August 1962. One sign reads: Burried [sic] here by Mayor Daley is his promise of a better community which will never come true. CHM, ICHi-014396; Larry E. Hemenway, photographer

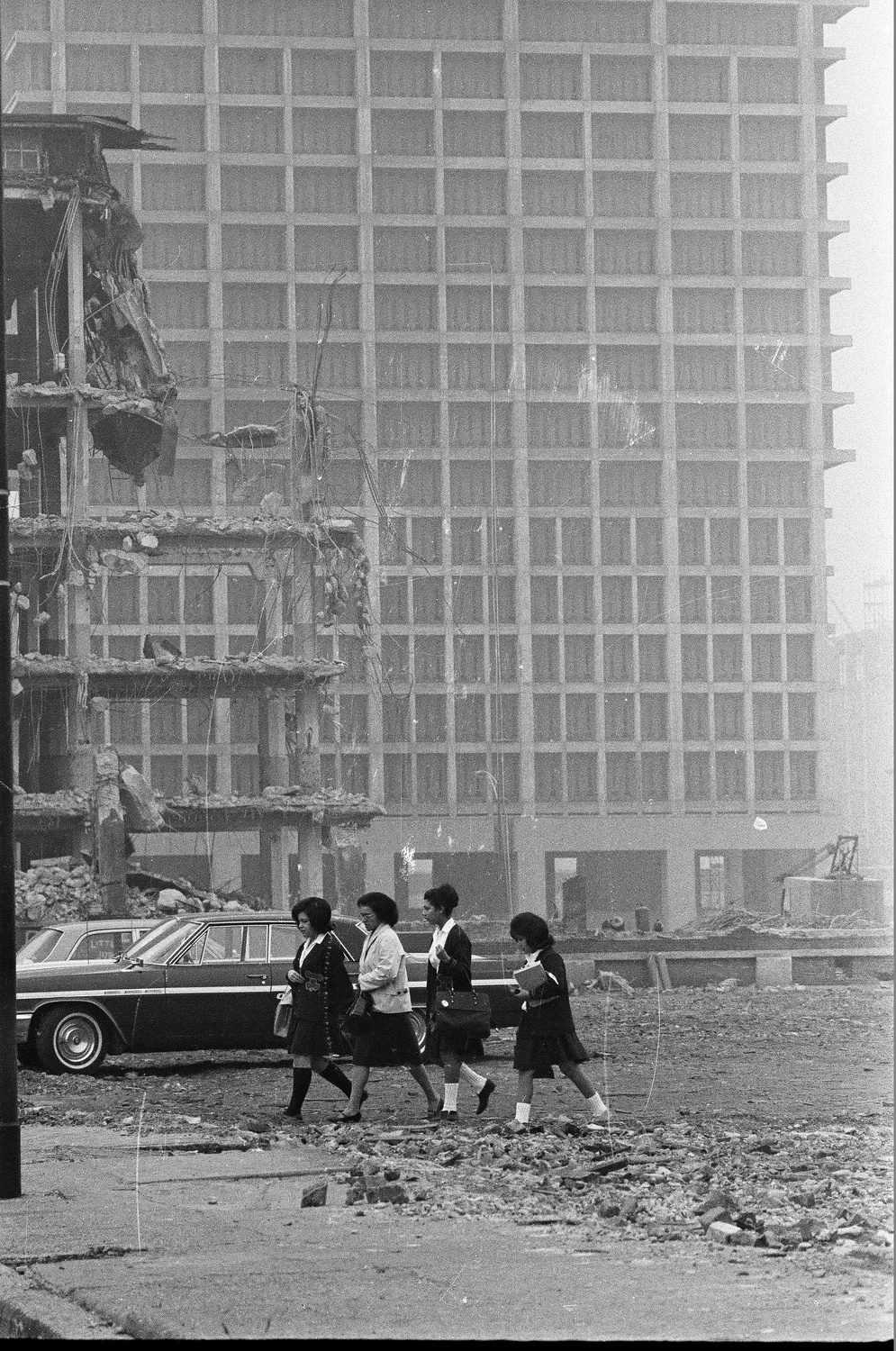

Residents rejected displacement by UICC, protesting for their right to remain in their homes. Ultimately, the Chicago City Council and UICC are responsible for the dislocation of the Near West Side community. UIC’s Circle campus came at the expense of 8,000 residents and 640 businesses (Siczek 2020). The specific intersection of Harrison and Halsted was home to a large Mexican community that had established itself over the course of 40 years.

This post will specifically focus on the Mexican population in the Near West Side, Hull-House services that aided their adjustment into the community, and their housing displacement stemming from the creation of the UICC campus.

Hull-House

Hull-House ensured access to cultural programs, English classes, clinics, and support from the Immigrant Protective League which would ensure a smooth transition for Mexican immigrants. The large Mexican population was able to find jobs in manufacturing, health care, railroad track laborers, and also within Hull House itself. The arts program at Hull-House fostered a creative expression amongst its participants who told their stories through art, especially pottery. Many of the Mexican residents were ceramicists in Mexico and found an opportunity to share their expertise with others. Eventually, the Hull-House Kilns opened avenues of income through pottery.

Jesús Torres, from Guanajuato, Mexico, immigrated to the US with his wife to find seasonal employment opportunities to make ends meet. Eventually they found themselves on the Near West Side where Jesús took a passionate and eventually professional interest in ceramics. Adrian Lozano was another professional artist who emerged from the Hull-House arts program. Lozano painted the first Mexican mural in Chicago and later went on to design the Mexican Fine Arts Center Museum expansion (now National Museum of Mexican Art), Benito Juarez High School, and the Little Village Arch, the first Chicago Landmark by a Mexican architect. Unfortunately, Lozano’s mural was buried under the rubble when UICC began construction.

Installation Photo from Jane Addams Hull-House Museum, photo by Elena Gonzales

Resistance and Politics

The creation of UICC’s campus targeted young men and wealthy suburban students who would attend the University, but also frequent local businesses owned by the same. This caused controversy as the University would not only displace a large community, but it would also redirect business from locals to University-owned shops. The Chicago Sun-Times echoed the Mexican community’s criticisms of the University and city officials, claiming that “the project failed its announced intentions and has systematically forced the poor, long-time residents out of the neighborhood.”

With threats of being uprooted, several members of the Mexican community joined forces with the other European community members to form the Harrison-Halsted Community Group. They often congregated in Hull-House. Florence Scala, an activist, was born and raised on the Near West Side where she became to be known as the “root and flower” of the neighborhood for her activist efforts and contributions. Scala’s background in urban renewal and city planning would aid her in leading the Harrison-Halsted Community Group, composed of Near West Side residents, in protests against the city and the University.

Residents gather in front of Guardian Angel School, 717 West Arthington Street, for a march on the city hall to protest the site of the new University of Illinois campus at Harrison Street and Halsted Street, Chicago, February 14, 1961. The site was originally slated for a housing development. ST-17600009, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

On October 9, 1962, several members of the Harrison-Halsted Community Group began a sit-in at Mayor Daley’s outer office which lasted several days. The objective of the sit-in was to “halt legal actions against property owners” until a judge could rule the project unconstitutional. The group was eventually removed from the outer office without an answer.

Exterior view of a neighborhood around the Near West Side, around West Monroe Street and South Paulina Street, Chicago, Illinois, November 10, 1964. ST-15001686-0004, Chicago Sun-Times collection, Chicago History Museum

Other government officials such as the US District Court Judge James B. Parson had disregarded the cries and claims of Near West Side residents by claiming that “community groups have no legal right to resist changes in the community if the changes promote the general welfare”. Rachel Cardero, resident of the Near West Side and member of the Community for United Latinas, expressed the organization’s frustrations to the media by posing the question, “If we were good enough to live here when the place was a slum, why are we being forced out now that the neighborhood has been rehabilitated?”

Aftermath

As the construction of the campus displaced residents of the Near West Side, another neighborhood changed as well: the growing Mexican neighborhood of Pilsen, located just south and east of the Near West Side. In the 1940s and 50s Pilsen was already home to the large Mexican community from the Near West Side that the Eisenhower Expressway had displaced. Now, thousands more displaced Latinxs joined them.

Despite UIC’s initial plans to attract wealthy Anglo students, the University has become a Hispanic Serving Institution (HSI). From 1971 to 1976, there was an increase in student-led mobilization against the University for underrepresenting its Latinx student population. These students, faculty, and political actors carried the mobilizations that demanded that the University include “education and justice for people of color” in their curriculum (University of Illinois Chicago). Eventually, the University underwent academic changes in the 70s that catered to its Latinx students in response to the protests. However, creating educational programs, support services, and celebrations of the arts does not compensate for the displacement of former Latinxs residents.

The tragic consequences of dislocation that Near West Side residents highlight the lack of planning and consideration that officials had when establishing UICC in the area. Although it is too late to reverse the actions of the University and city officials, the Near West Side can serve as an example for urban developers and universities who are looking to establish institutions. Thoughtful planning and consideration is required to avoid repeating the story of the Near West Side.

For National Bike Month, CHM research and insights analyst Marissa Croft writes about sewing a women’s bicycle costume using an 1897 pattern from the Abakanowicz Research Center.

Daisy, Daisy, give me your answer, do!

I’m half crazy, all for the love of you!

It won’t be a stylish marriage,

I can’t afford a carriage,

But you’ll look sweet, upon the seat,

Of a bicycle built for two!

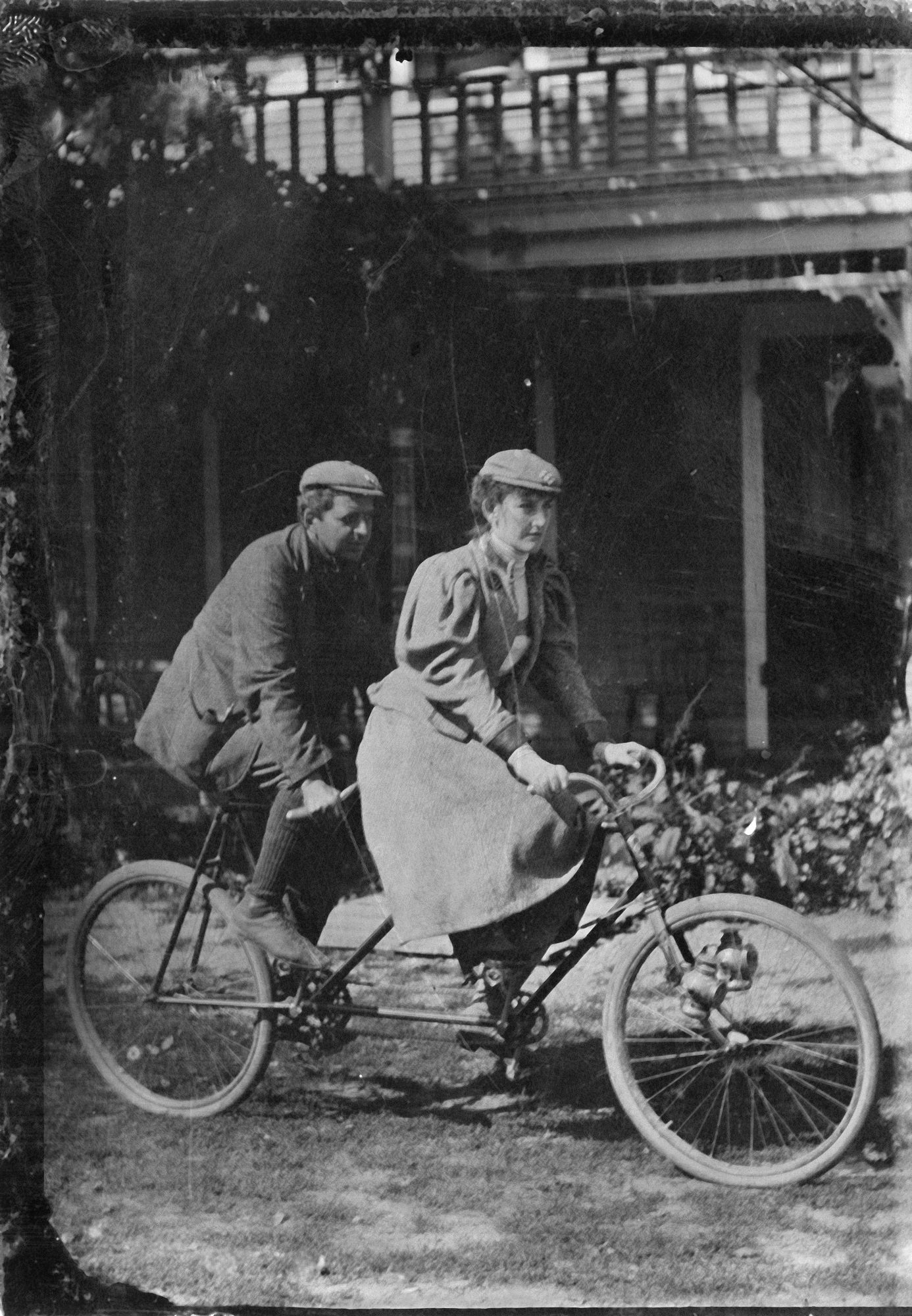

Mae Sawyer Stibgen riding a tandem bicycle with unidentified man on an outing with the Lincoln Cycling Camera Club, September 20, 1896. CHM, ICHi-020570

In 1892, Harry Dacre penned the popular song “Daisy Bell” shortly after the invention of the safety bicycle, the style most of us ride today. The safety bicycle brought cycling to the masses because unlike the Penny Farthing with its enormous front wheel that would send riders flying over the handlebars, it was vastly more affordable, comfortable, quick, and, well, safe. These improvements made cycling more accessible to women in search of thrill, like early women’s cycling champion Kitty Knox. In an era where floor-length skirts were the norm, what would Daisy Bell have worn to peddle properly during her wedding on wheels?

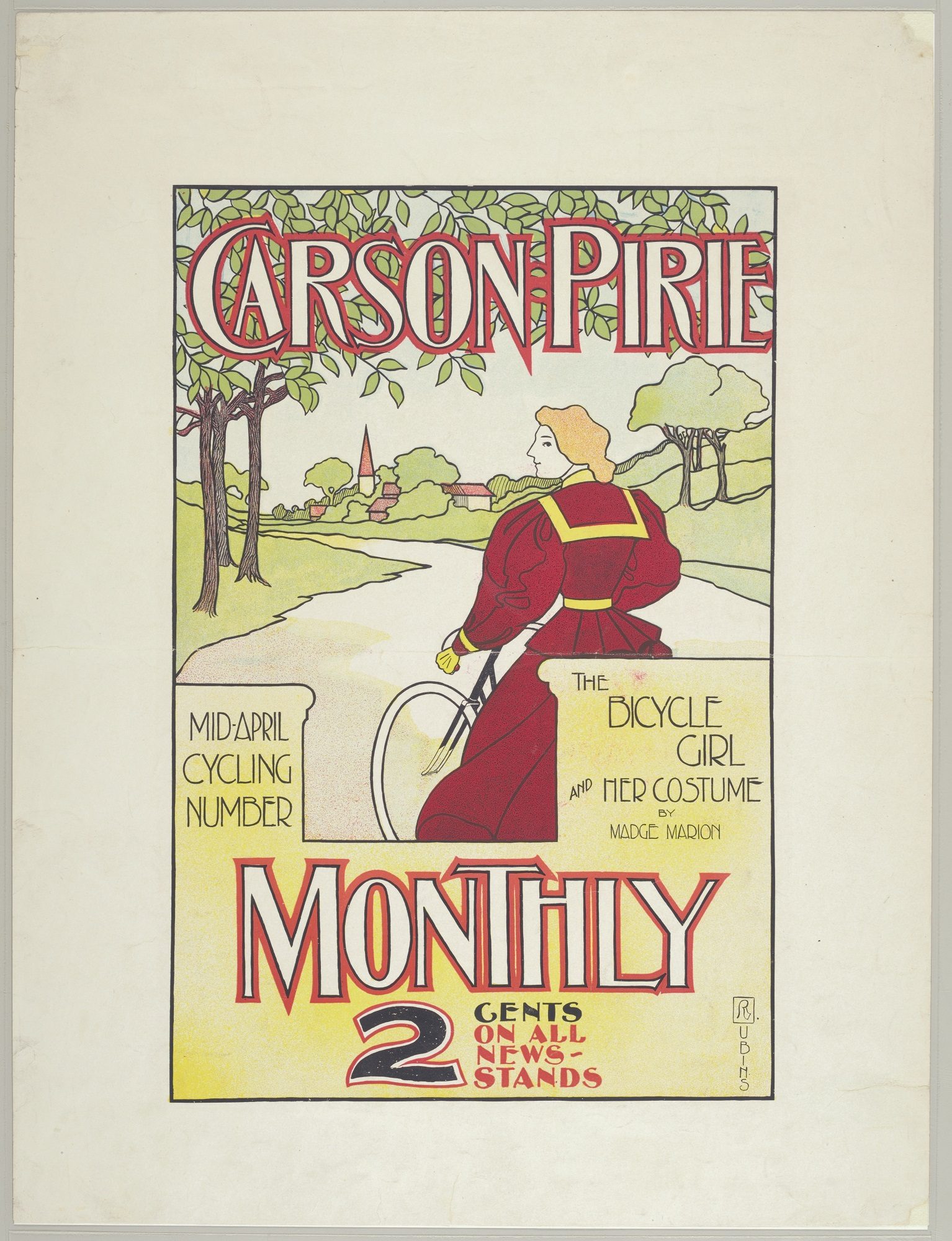

Broadside advertising Carson-Pirie Monthly Mid-April Cycling Number, featuring The Bicycle Girl and Her Costume by Madge Marion, Chicago, 1896. CHM, ICHi-076879

Cycling costumes for women of the 1890s took a few different forms and offered a variety of ways to preserve the cyclist’s modesty without sacrificing mobility. From shorter skirts to bloomers, the bicycle girl and her clothes soon became synonymous with modern, mobile, girls-on-the-go.

Women’s bicycle outfit by Marshall Field & Co., 1887. CHM, ICHi-066361

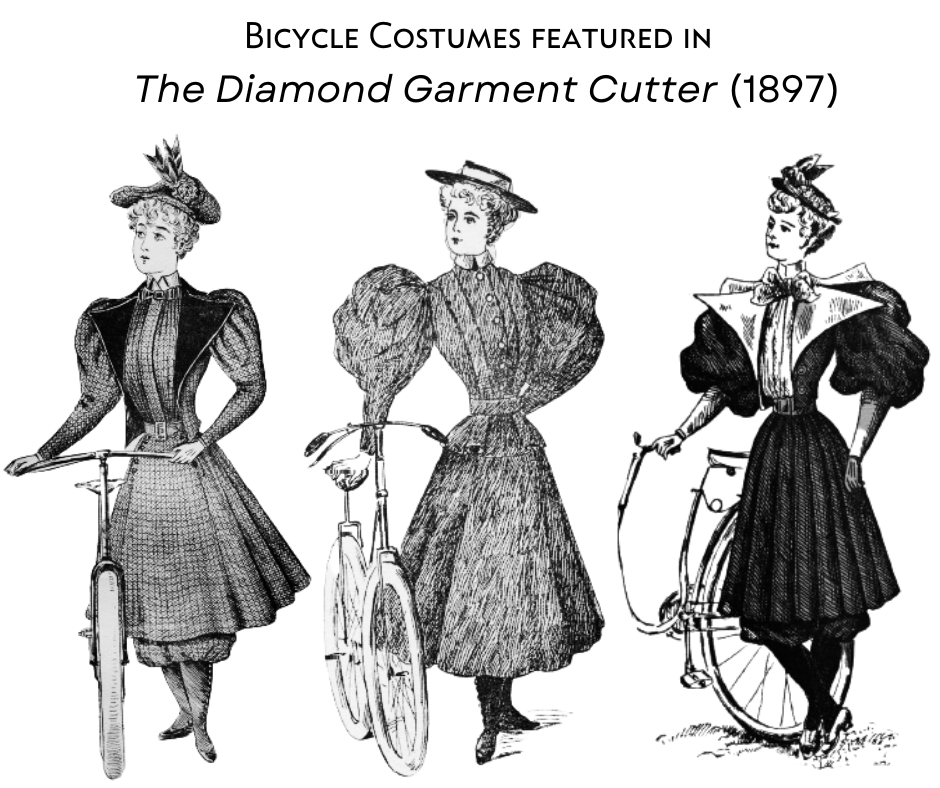

As a casual cyclist and fashion history enthusiast, I’ve often wondered about how comfortable it actually was to ride in these costumes. During a research appointment at the Abakanowicz Research Center, I came across a set of pattern books by Chicago tailor W. H. Goldsberry. These books contained detailed schematics for creating men’s, women’s, and children’s clothing of the 1890s, and I was delighted to see that the 1897 edition contained THREE different patterns for women’s cycling costumes!

It was the third costume that caught my eye: a gathered skirt, bloomers, and a jacket with enormous sleeve style the book said was “called the Ferris wheel sleeve.” The name was most certainly an attempt to cash in on the hype from the first Ferris wheel’s debut at the 1893 world’s fair. I knew I had to make this costume and see if the sleeve truly lived up to its name!

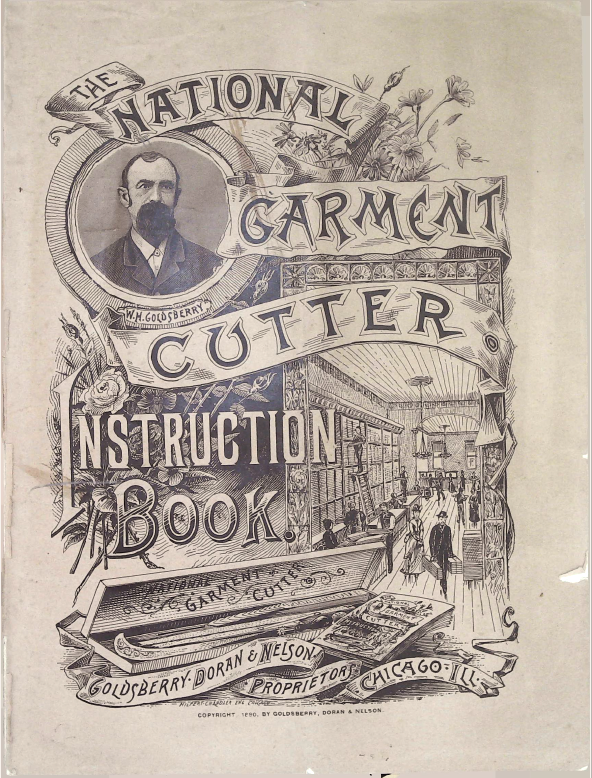

The cover of the 1880 National Garment Cutter instruction book.

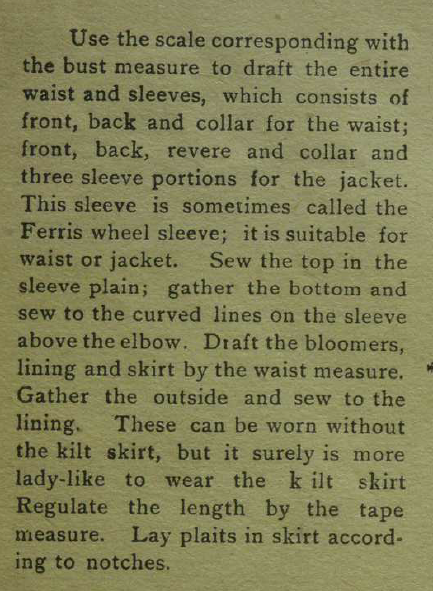

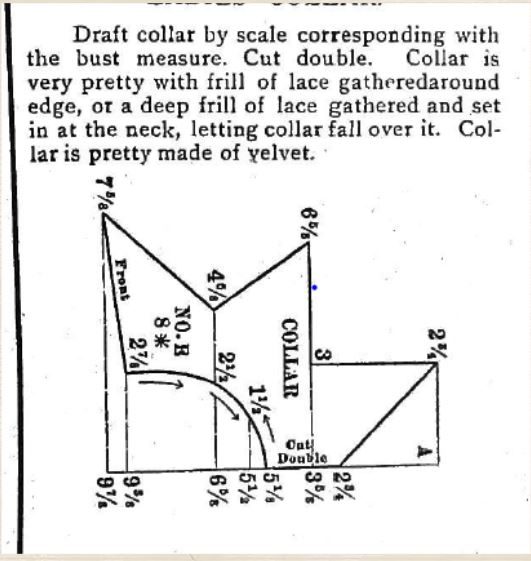

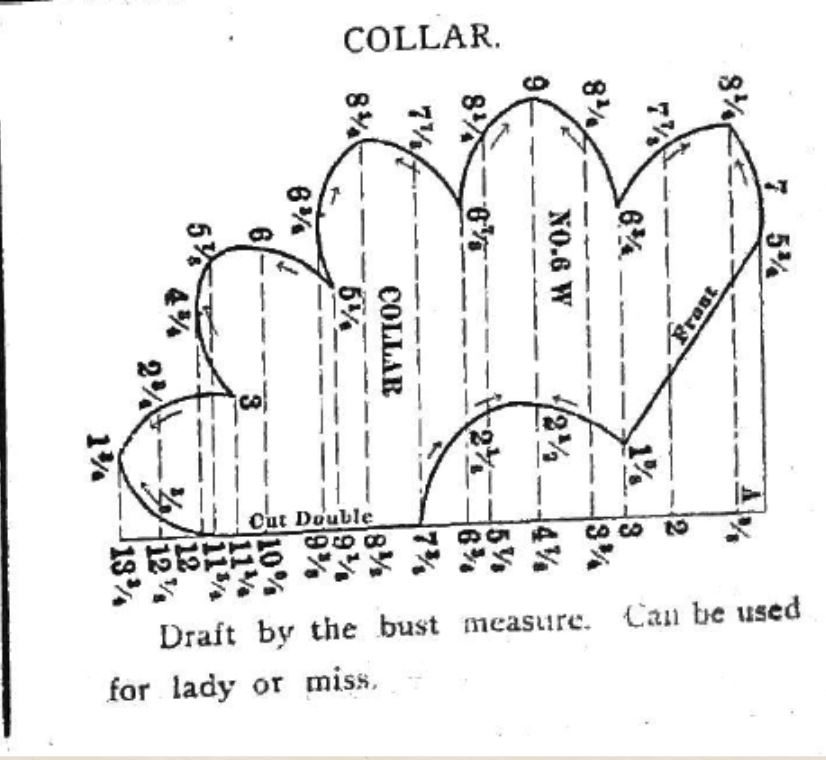

The Diamond Garment Cutter system (initially called the National Garment Cutter system) relies on scaling up diagrams using apportioning rulers. A sewist would select a ruler that corresponded to the wearer’s chest or waist measurement, and then copy the diagram onto paper, using the numbers given on the diagram as a reference. The rulers’ markings were spaced closer or further together, so that the resulting pattern would automatically be scaled up or down to fit the wearer’s measurements. This system was intended to greatly simplify pattern drafting, with the authors boasting that, “None have ever before reduced the art of cutting everything worn to but one system and rendered that one so simple that a child can understand, and but with few instructions successfully operate it.” (The National Garment Cutter General Directions, 1884). If you’d like to try your hand at making something from these patterns, I’ve included detailed instructions in a separate blog post.

An example of the sparse directions accompanying these patterns.

Once I’d patterned the jacket and bloomers, I realized I wouldn’t have enough fabric to make the kilt skirt that goes over the bloomers, but luckily the instructions said the ensemble “can be worn without the kilt skirt, but it surely is more lady-like to wear the kilt skirt.” Here’s to being un-lady-like!

Left: Women’s bicycle costume from The Diamond Garment Cutter Book of Diagrams by W.H. Goldsberry, 1897. Right: Marissa Croft, 2022. Photographs by Marissa Croft

Final review of the cyclability of this outfit? I’ve worn it to bike around Chicago and the outdoors several times now, and the bloomers are extremely comfortable. The loose fit ensures your legs stay cool and protected from the sun, and their massive volume (paired with the Ferris wheel sleeves) also increases your visibility on the road to motorists. So, whether you choose to ride around on a bicycle built for one or two, I highly endorse mixing it up and giving cycling bloomers a try!

Learn More

- PDF of patterns for the three Ladies’ Cycling Costumes

- Research fashion history at the Abakanowicz Research Center using the Costume Research Files.

- CHM Costume and Textiles Image Gallery

- Costume and Fashion Research Library Guide

- Follow my sewing projects on Instagram: @sinistra.marissa

A Tutorial on Using the National/Diamond Garment Cutter Systems

Would you believe me if I told you that drafting custom patterns for historical clothing could be as easy as playing connect-the-dots? And that hundreds of these patterns are already available for free?

Welcome to the world of pattern drafting manuals of the late 19th century! These books were created as an alternative to paper patterns and promised their users greater flexibility in sizing, since the pieces were drafted individually according to the wearer’s measurements. The system depended upon the use of sets of rulers called “apportioning scales/rulers.”

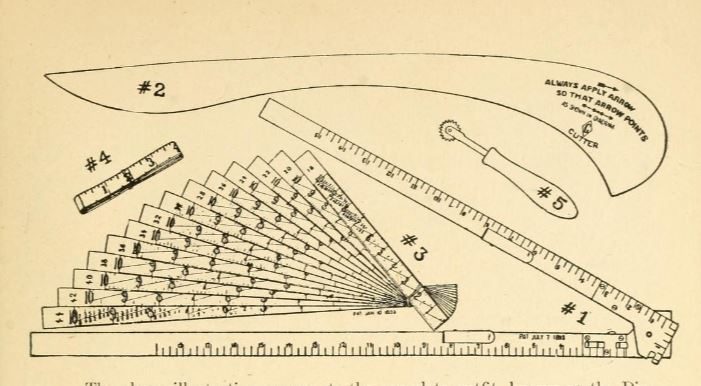

Object #3 in this diagram is what the original apportioning rulers for this system looked like. Instruction Book by the Diamond Garment Cutter Correspondence School, 1903, pg. 3)

An apportioning ruler is a ruler where the numbers are not spaced according to inches or centimeters, but instead are placed further or closer together depending on how much you need to scale a pattern piece up or down from the base pattern to fit either your chest or waist measurement. When you copy the numbers on the diagram over to a new piece of paper using the correct apportioning ruler, the resulting pattern piece will fit whatever measurement you initially selected!

One popular system that uses apportioning rulers was invented in Chicago and I’ve found it to be a game-changer for sewing historically accurate costumes. Initially launched as the National Garment Cutter System in 1884, it was renamed the Diamond Garment Cutter System in the 1890s and also gained an accompanying periodical titled The Voice of Fashion, which offered subscribers more up-to-date patterns. Unlike many of their competitors, these books contained clothing patterns for men, women, and children.

| Year | Book | Link |

| 1884 | The National Garment Cutter by Goldsberry, Doran and Nelson | Scan available on Archive.org |

| 1888 | The National Garment Cutter Book of Diagrams by Goldsberry, Doran, and Nelson | Scan available on Archive.org |

| 1890 | The National Garment Cutter Book of Instructions and Diagrams by Goldsberry, Doran, and Nelson | Instruction book and Diagram Book available at the Abakanowicz Research Center |

| 1892 | Voice of Fashion [Summer] | Available at the Abakanowicz Research Center |

| 1895 | The Diamond Garment Cutter by Goldsberry, Doran, & Nelson | Scan available on Archive.org |

| 1897 | The Diamond Garment Cutter Book of Diagrams by W. H. Goldsberry | Available at the Abakanowicz Research Center (Contains three patterns designed for those with chest measurements between 38 and 45 inches) |

| 1897 | Voice of Fashion [Fall] | Scan available on Archive.org |

| 1897 | Voice of Fashion [Winter] | Scan available on Archive.org |

| 1900 | Voice of Fashion [Spring and Summer] | Available at the Abakanowicz Research Center |

| 1901 | Voice of Fashion [Summer and Fall] | Available at the Abakanowicz Research Center |

| 1903 | Instruction Book by the Diamond Garment Cutter Correspondence School | Available on Archive.org, this book has the clearest directions on using the system and adjusting patterns to fit different body types |

I’ve created several projects using these books and the apportioning rulers from the American Seamstress and have been impressed by how easy it is draft the pattern pieces. The best part is that there’s not a bit of math involved, all you must do is read numbers on a diagram and ruler! Keep reading for an explanation on how it’s done.

Ladies’ Street Costume (Diamond Garment Cutter Book of Diagrams, 1895, p. 52)

Ladies’ Bicycle Costume with Ferris Wheel Sleeves, (Diamond Garment Cutter, 1897, p. 82)

Ladies’ Visiting Costume (Diamond Garment Cutter Book of Diagrams, 1897, p. 17)

Tutorial

To create a pattern from these books that fits you, you will need:

- Gridded paper (wrapping paper with a grid on the back works well)

- Reproductions of the original apportioning rulers from Mrs. Depew

- A French curve

- A ruler

- A marker

- Scissors

Following the instructions on the pattern you select (“use scale corresponding with bust/waist/chest measure”), pick a ruler that matches the specified body measurement. For instance, if your waist measurement is 32, use the ruler that says “32” at the top.

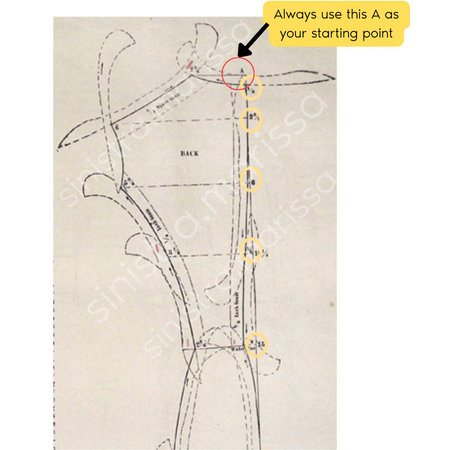

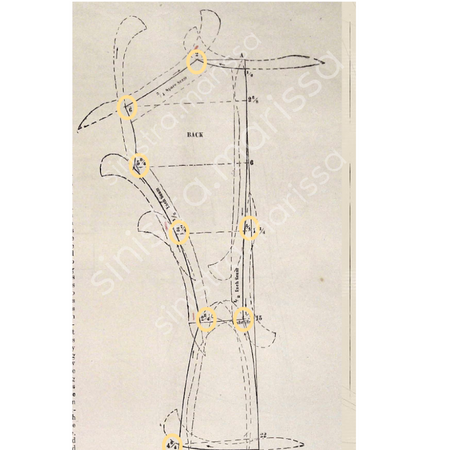

Step 1: Draw a large right angle on your grid paper, then use your selected ruler to make markings at the points corresponding to the numbers on the vertical axis of the diagram, starting where it says “A,” and then moving down (I find it helpful to label each point with the number it matches with in the diagram).

Step 2: Using the markings that you just made on the vertical axis as your starting points, repeat this process of measuring and marking the points on the horizontal axis. You should be left with something that looks like an unfinished connect-the-dots puzzle.

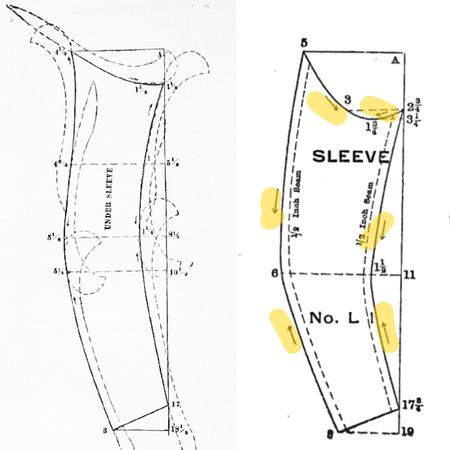

Step 3: Using your French curve and straight edge where necessary, connect the dots of your pattern to match the shape of the original diagram illustration. Your French curve’s largest side always points in the direction specified by the arrows on the original diagram (highlighted in right illustration). This will leave you with a pattern piece properly scaled up to your size, though you may still need to adjust it, so always do a mockup or a tissue fitting first.

Important: Wherever a pattern piece indicates “cut double” that means cut it out on the fold of the fabric! A seam allowance of roughly ¾ an inch is also included on these patterns, and they’ll note where this is not the case, usually at the shoulder seams.

Even if you’re familiar with how clothes are put together, creating a finished garment from these pattern pieces can be quite challenging because there are little to no directions of how the pieces need to be assembled. Studying pictures of extant garments can be helpful and I also recommend starting with something simple like these two detachable collars below, both taken from the 1897 Diamond Garment Cutter Book of Diagrams, page 19. Once you get the hang of it, you’ll have literally hundreds of free, historical patterns at your fingertips! Happy sewing!

Further Reading

- Remaking History: Sewing a Women’s Bicycle Costume from an 1897 Pattern

- PDF of patterns for the three Ladies’ Cycling Costumes

- Research Fashion History at the Abakanowicz Research Center using the Costume Research Files

- CHM Costume and Textiles Image Gallery

- Costume and Fashion Research Library Guide

- Follow my sewing projects on Instagram: @sinistra.marissa

May is Jewish American Heritage Month. In recognition, CHM curator of religion and community history Rebekah Coffman highlights materials from the Abakonowicz Research Center related to the National Council of Jewish Women.

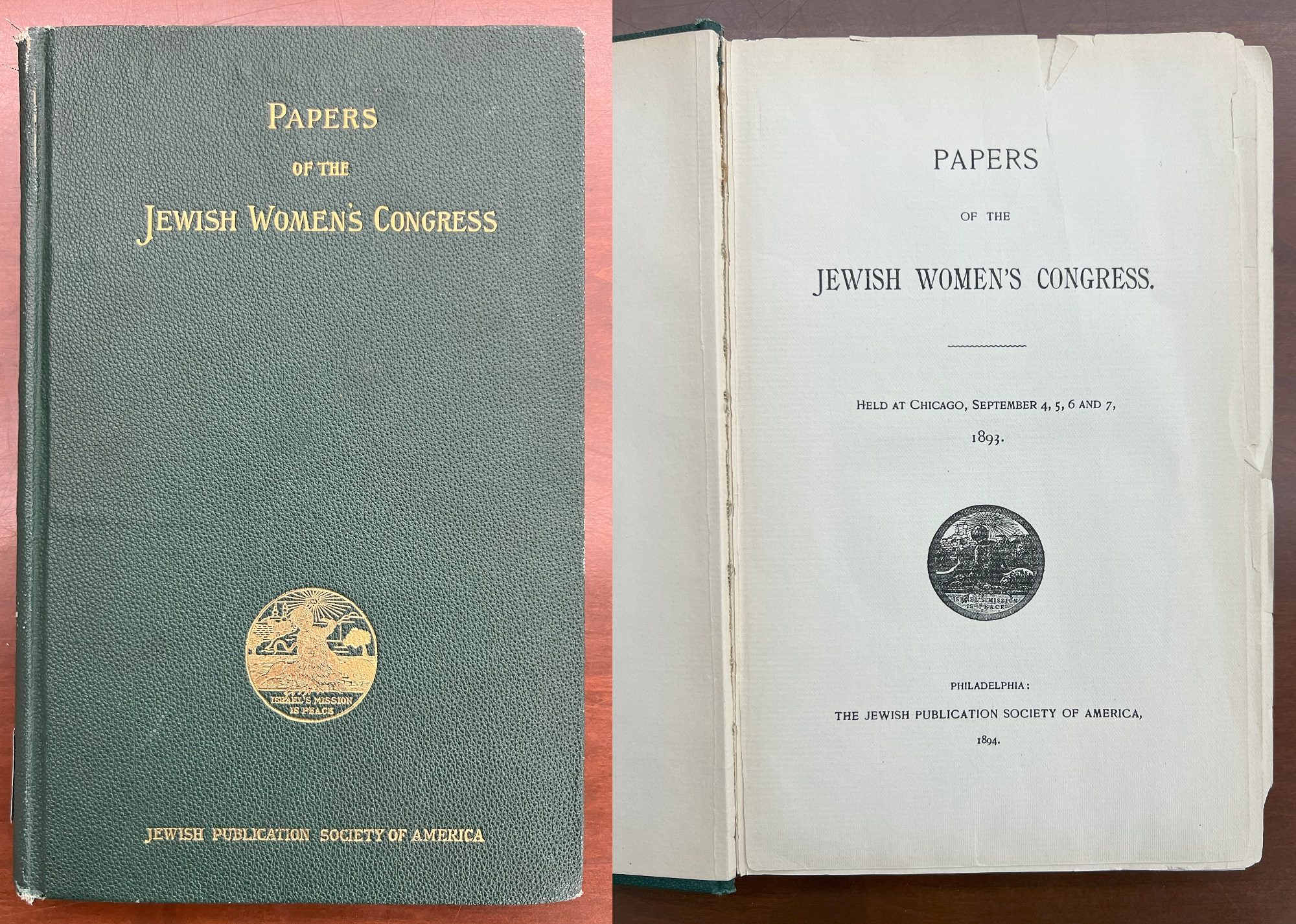

The National Council of Jewish Women is the result of a gathering of Jewish women that took place during the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition (WCE). In addition to the better-recognized national pavilions and Midway activities of that world’s fair, numerous ancillary activities were held, including the World’s Parliament of Religions. This gathering included representation from and congresses about religious representation, including denominationally specific committee gatherings. One such meeting, held by the Jewish Women’s Committee, became known as the Jewish Women’s Congress (JWC). The congress was held September 4–7, 1893, and saw participation by ninety-three delegates from twenty-nine cities. At its conclusion, the congress voted to establish the National Council of Jewish Women (NCJW), an organization still active today.

Papers of the Jewish Women’s Congress, 1894. E184.J5 J5 1893.

The NCJW was founded and chaired by Hannah Greenebaum Solomon (1858–1942), who was born to Sarah and Michael Greenebaum and raised in Chicago as one of ten children. She was active in both religious and social circles as a member of Temple Sinai synagogue and, along with her sister Henrietta, as the first Jewish members of the Chicago Women’s Club. As chair of the JWC, Solomon made the strategic move to shift the gathering of Jewish women from the WCE’s Women’s Building to the World’s Parliament of Religions, centering the philanthropic aims of the gathering and planning for its future initiatives.

Portrait of Hannah Greenebaum Solomon, c. 1915. CHM, ICHi-088576

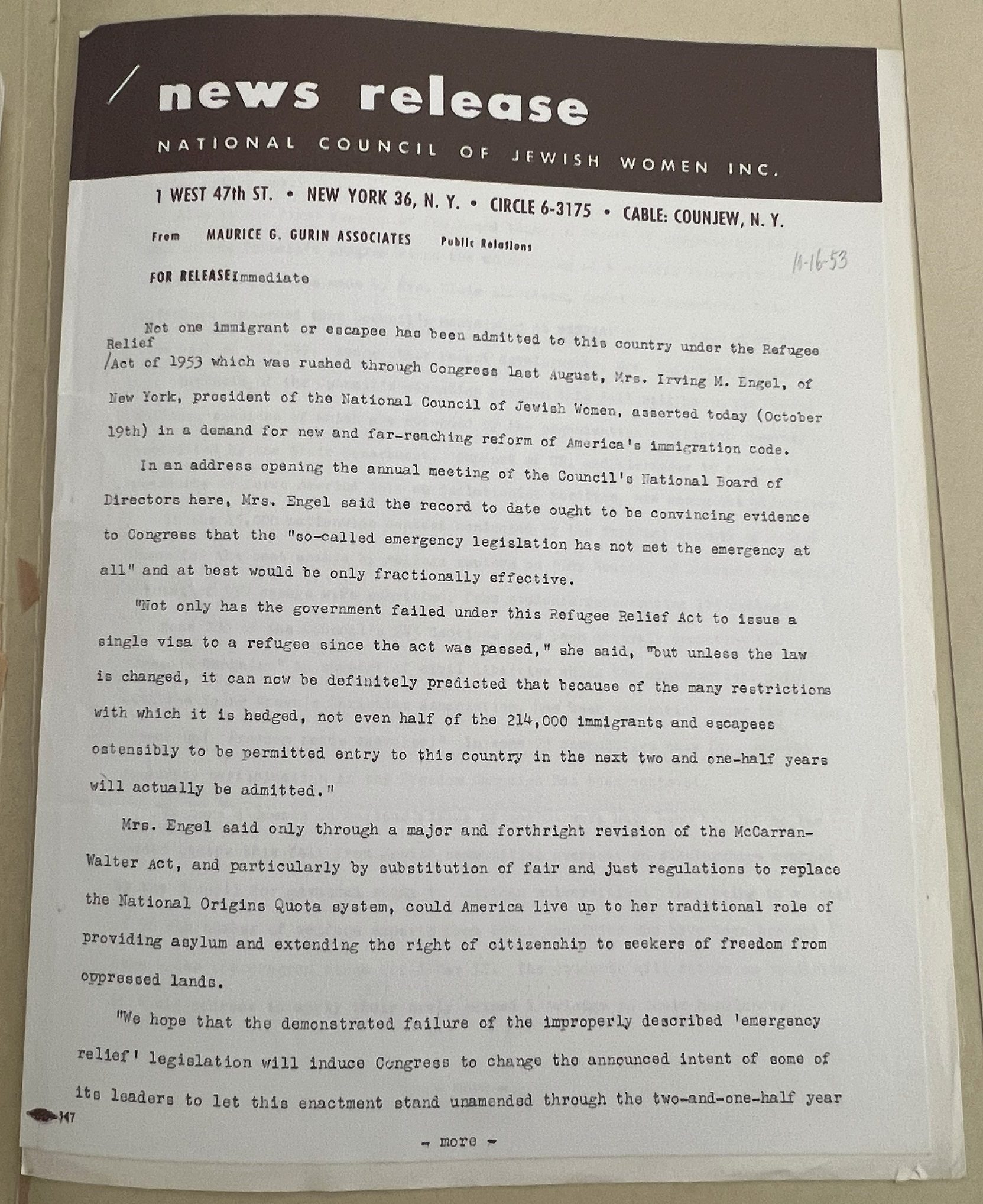

At its founding, the heart of the NCJW’s work was religious education for women and children. As the organization grew, it expanded its missional focus into broader philanthropic efforts, with a special emphasis of providing aid to immigrants. This included facilitating social services for young Jewish women through providing housing, vocational training, and other services to acculturate to American life.

Press release discussing immigration reform, dated October 16, 1953. Box 7, folder 2, “Council of Jewish Women; Community Service and Activities; Misc. Immigration”

Through Solomon’s connections, the NCJW remained allied with other organizations providing aid services, including Jane Addams and Hull-House. The NCJW’s membership grew quickly following its inaugural meeting, growing from its original ninety-three members in 1893 to more than 50,000 members by 1925.

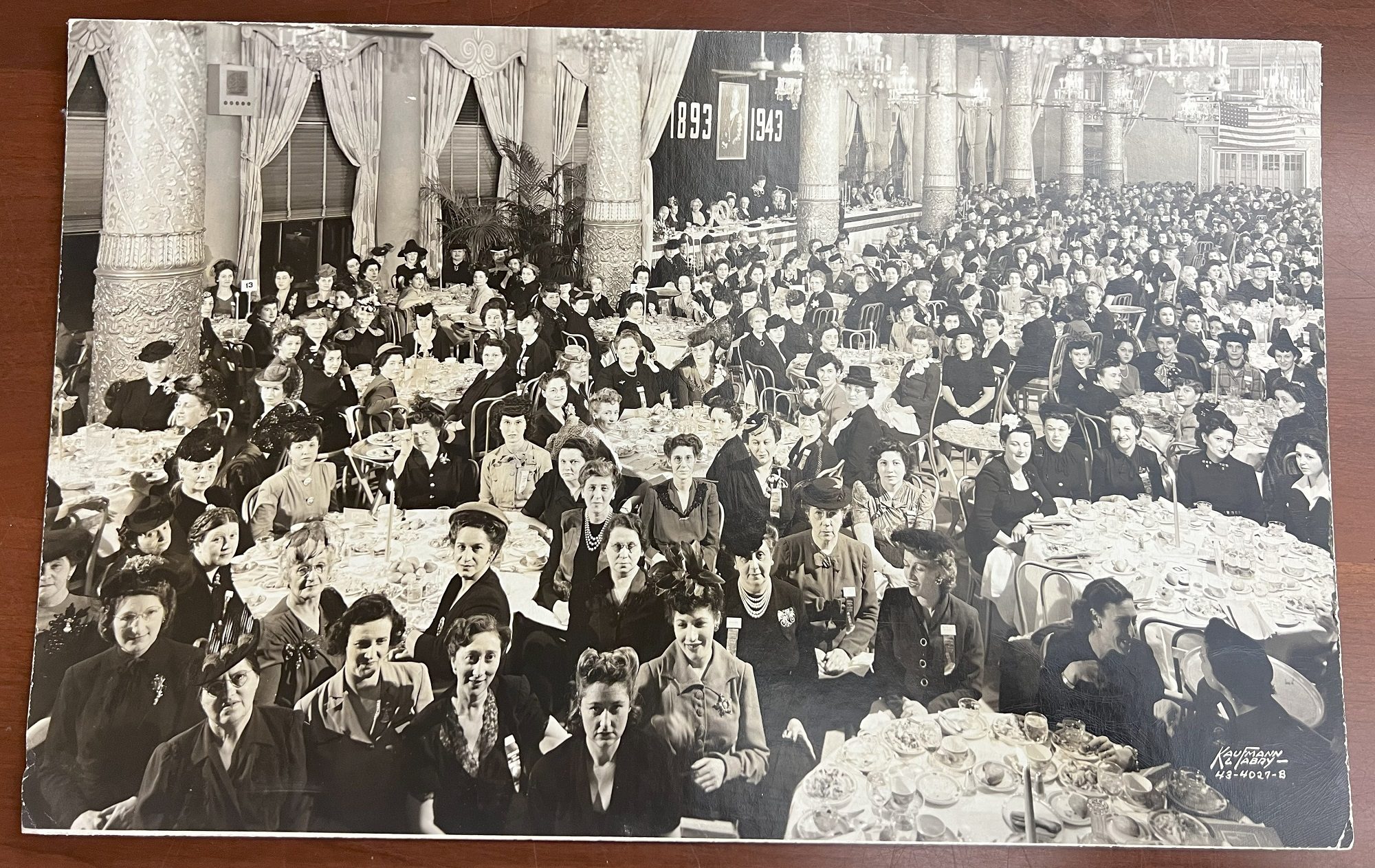

50th Anniversary Banquet of the National Council of Jewish Women, 1943.

In the early twentieth century, the NCJW expanded its advocacy and aid efforts as it fundraised for war relief during World War I, campaigned for passage of women’s suffrage in 1919, advocated for jobs during the Great Depression, and fought against racial discrimination. During World War II, it was active in a wide cross section of relief efforts, including working with displaced persons. The NCJW’s growth continued postwar and, by 1970, it boasted over 110,000 members. Its mission, too, continued to grow and shift as the organization saw the country’s philanthropic needs transform.

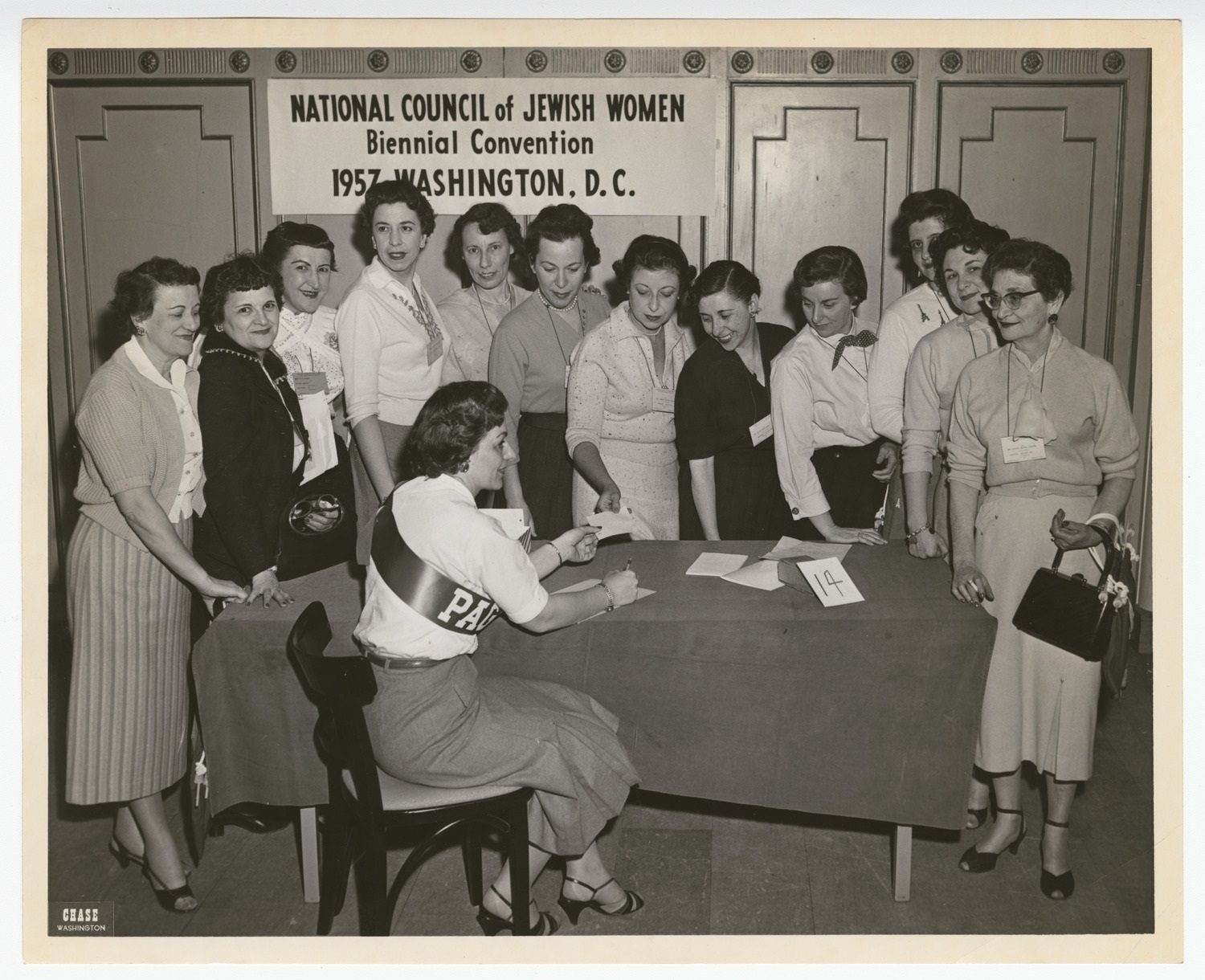

Women gathered around a table at the National Council of Jewish Women 1957 Biennial Convention in Washington, DC. CHM, ICHi-088573

Today, the legacy of the NCJW continues through its continued presence as a grassroots organization centered on advocacy and political activism with approximately 210,000 members who are active in all fifty states and internationally. Through a Jewish lens, the NCJW advocates for pluralistic human rights issues including reproductive rights, voters’ rights, and resources for refugees.

Lions in front of the Art Institute of Chicago crowned with flower wreaths in honor of the 75th anniversary of the National Council of Jewish Women, 1969. ST-30000413-0004 (top) and ST-30000412-0002 (bottom), Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Art Institute lions wreath ceremony by group from the National Council of Jewish Women, 111 South Michigan Avenue, Chicago, Illinois.

These efforts expand the original mission of the NCJW and speak to the legacy Hannah Solomon identified in 1893: “The influence of the Congress is . . . not to be measured by the size of its audiences, nor by the merits of its papers. Its chief result is that it brought together, from all parts of the country, East, West, and South, women interested in their religion . . . Its outcome is a National Organization, and its use was to prove to the world that Israel’s women, like women of other faiths, are interested in all that tends to bring men nearer together in every movement affecting the welfare of mankind.”

Additional Resources

- View the papers of the Jewish Women’s Congress at the Abakanowicz Research Center, which is free to visit

- See more images related to the National Council of Jewish Women

The coronation of George VI on May 12, 1937, was the first to be filmed, first to be broadcast on radio, and the first where “the colored press had fully accredited representatives at such an historic occasion.” In this blog post, take a look at archival materials that document and give insight into the historic assignment undertaken by two Black journalists for the Associated Negro Press.

In 1919, a pivotal year for race relations in both Chicago and the United Kingdom, the Associated Negro Press (ANP) was established by Claude A. Barnett (1889–1967) in Chicago. With correspondents and stringers in all major centers of Black population, the ANP provided its member papers—the vast majority of Black newspapers—with a twice-weekly packet of national and international news that gave African American newspapers a critical, comprehensive coverage of personalities, institutions, and events relevant to the lives of Black Americans. Even as a relatively young news agency, the ANP sought to establish its voice on an international level. By 1945, it had a vast international network that expanded to Africa and London, bringing global awareness to important issues within Black communities through the lens of the Black American experience, including increased attention to civil rights concerns and the fight against persistent racism.

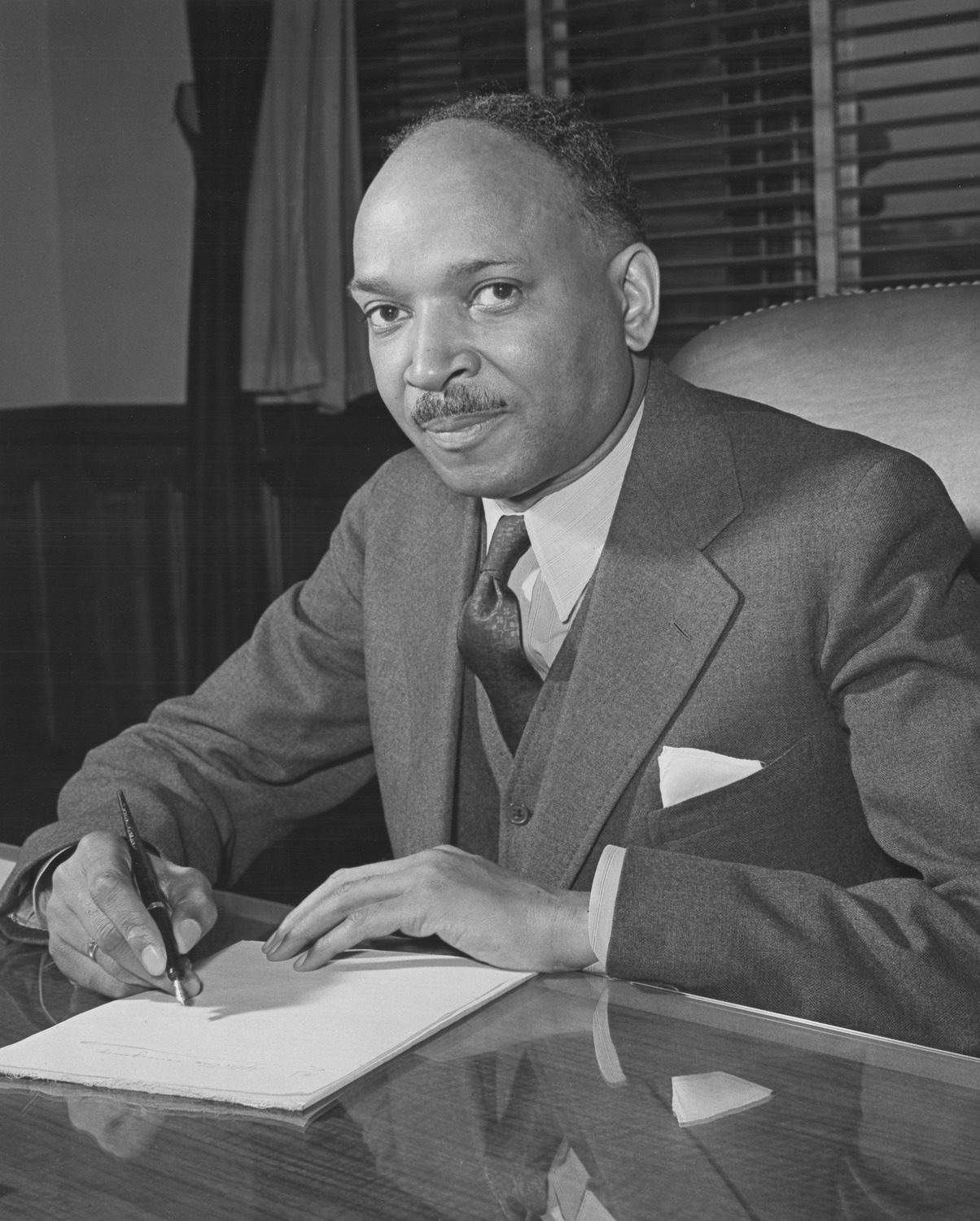

Undated photograph of Claude A. Barnett at a desk. CHM, ICHi-061826

In 1937, the ANP took strides toward expanding its international coverage through designating Fay M. Jackson (1902–1988) as foreign correspondent to Europe for six months with a central mission to cover the coronation of George VI. An ambitious and impressive force in journalism, Jackson’s precocious and straightforward writing style fore fronted her voice as a Black American journalist, a style that matched and amplified the reporting mission of the ANP.

Undated portrait of Fay M. Jackson. CHM, ICHi-022288

Born in Dallas, she moved to Los Angeles with her family at the age of 14. Jackson attended Polytechnic High School (’22), where she wrote for the school newspaper, followed by the University of Southern California (’27), where she studied journalism and philosophy. While still a college student, she wrote for the California Eagle and Pacific Defender, two LA-based Black newspapers, and was critical of USC’s institutional racism, as well as the hypocrisy of having such policies while affiliated with the Methodist Church. After graduating from USC, Jackson continued her journalistic pursuits: she started Flash magazine in 1928, served as the first African American female Hollywood correspondent accredited by the Motion Pictures Director’s Association, and was named the political editor of the California Eagle in 1931.

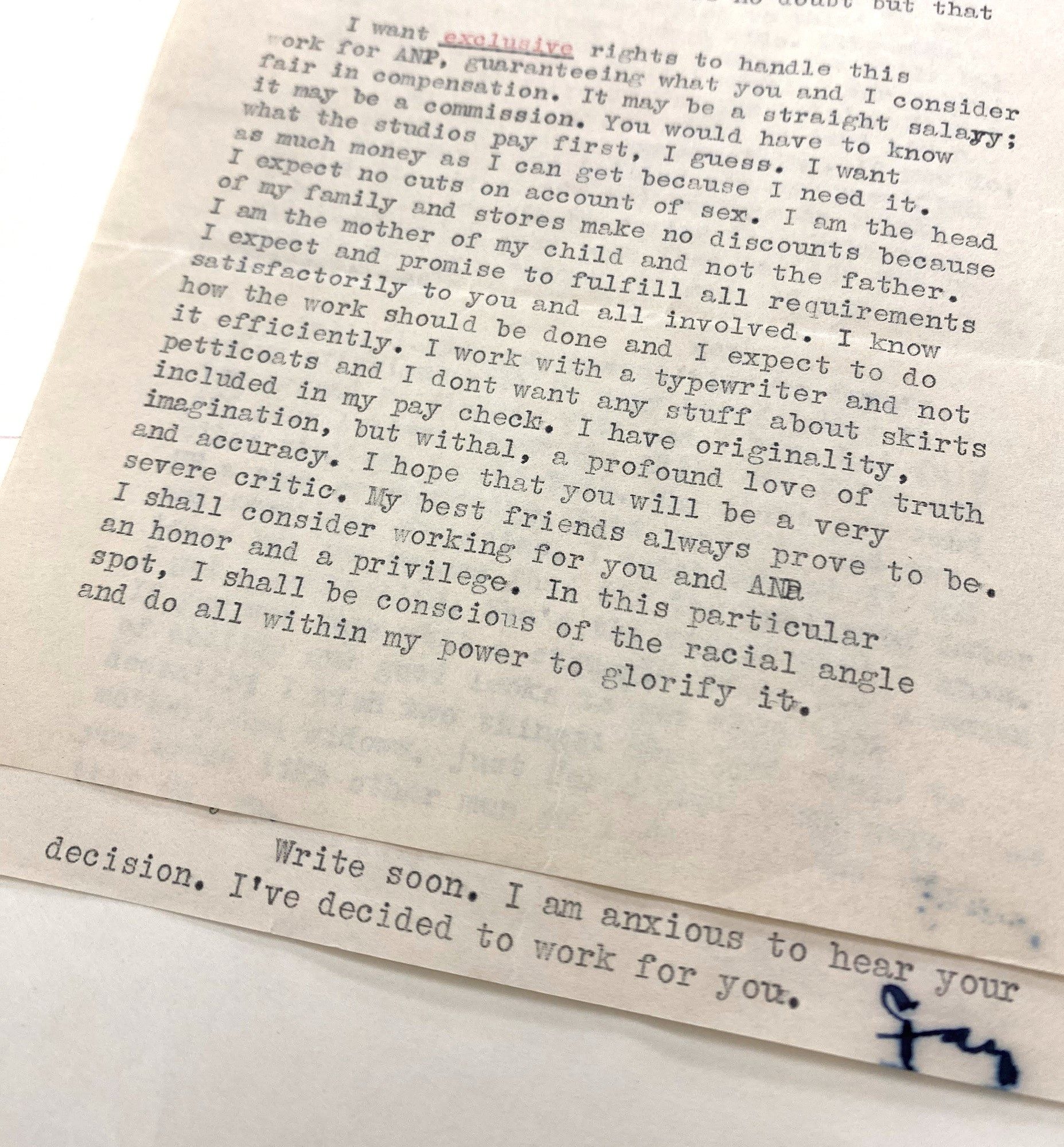

The earliest correspondence between Fay Jackson and Claude Barnett in the CHM Research Collections dates from 1933 with Jackson asserting her abilities and being forthright about her salary expectations. Barnett, impressed by her confidence, was not put off by such grand statements, and Jackson was appointed the Pacific Coast Representative for the ANP in November 1933.

Letter from Jackson to Barnett dated August 23, 1933, in which Jackson signs off with “I’ve decided to work for you,” even before she is officially hired. Claude A. Barnett papers, 1918–67, box 287, folder 1.

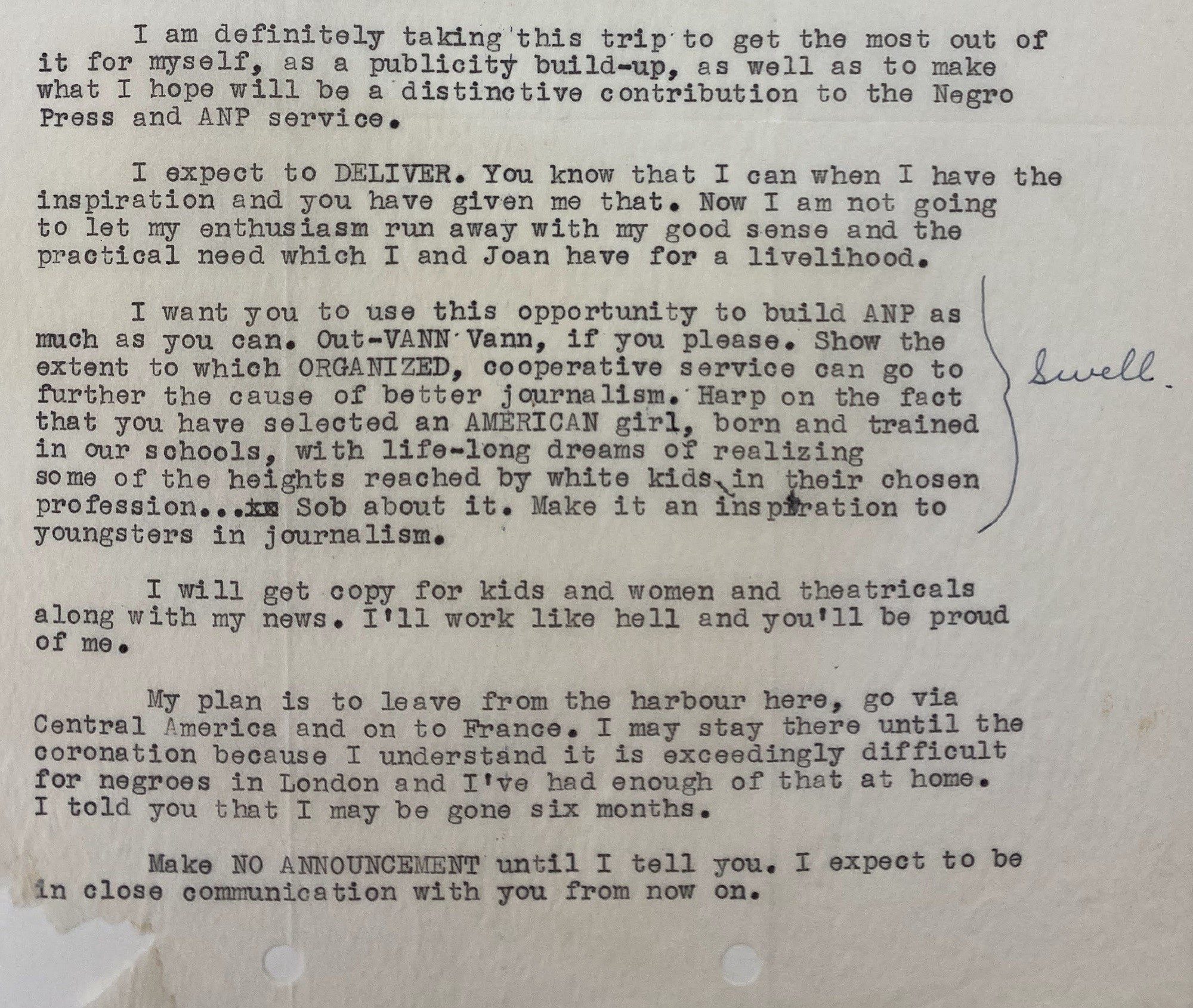

In October 1936, Barnett offered Jackson the opportunity to cover the coronation of George VI with Rudolph Dunbar (1899–1988), the ANP’s London correspondent. Jackson made her enthusiasm clear in her response: “I want you to use this opportunity to build ANP as much as you can . . . Show the extent to which ORGANIZED, cooperative service can go to further the cause of better journalism. Harp on the fact that you have selected an AMERICAN girl, born and trained in our schools, with life-long dreams of reaching some of the heights reached by white kids in their chosen profession . . . Make it an inspiration to youngsters in journalism.”

Excerpt of letter from Jackson to Barnett dated October 24, 1936, on which someone, most likely Barnett, approves of a paragraph with “Swell.” Note how Jackson describes London at the time. Claude A. Barnett papers, 1918–67, box 288, folder 1

Jackson’s coverage of the coronation came during a critical period for the United Kingdom, as the nation was transitioning from its status as the British Empire to a series of independent states known as the Commonwealth, precipitated by the 1931 Statute of Westminster just a few years earlier. Consequently, George VI’s reign would come during a decisive time both in terms of confronting the country’s status as a global power and in terms of national identity. Within just a few short years, the UK would find itself at war, and, within a decade, the process of decolonization would be accelerated as more former British colonies sought independence, including India and Pakistan in 1947.

Excerpt of correspondence from Jackson to Barnett, dated November 3, 1936.

Evidence of these underlying racial tensions painted Jackson’s perspective as she planned her itinerary. In a letter dated November 25, 1936, Jackson expressed a desire to stay longer in Paris than in London due to her hesitation about the treatment of Black people in Britain. After arrangements were made and accommodations were settled, Jackson left for Europe in early 1937 on an ocean liner from New York, traveling through continental Europe to report on the racial climate there.

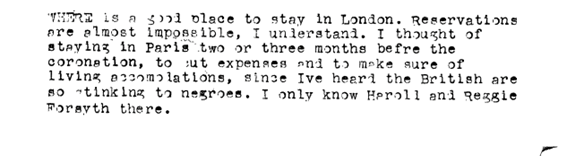

As the date of George VI’s coronation approached, arrangements were made for Jackson and Dunbar to attend. A telegram to ANP a few days before the event requested payment for seats.

Telegram from Jackson to the ANP, May 8, 1937. According to the Bank of England inflation calculator, £3 in 1937 would be £163.59 in February 2023, which would be $202.43 today. Claude A. Barnett papers, 1918–67, box 288, folder 1.

George VI ascended to the throne in January 1936, and his coronation was the first to which African royalty were invited. However, as Jackson would report, this did not mean an equal Black representation in all elements of coronation activities.

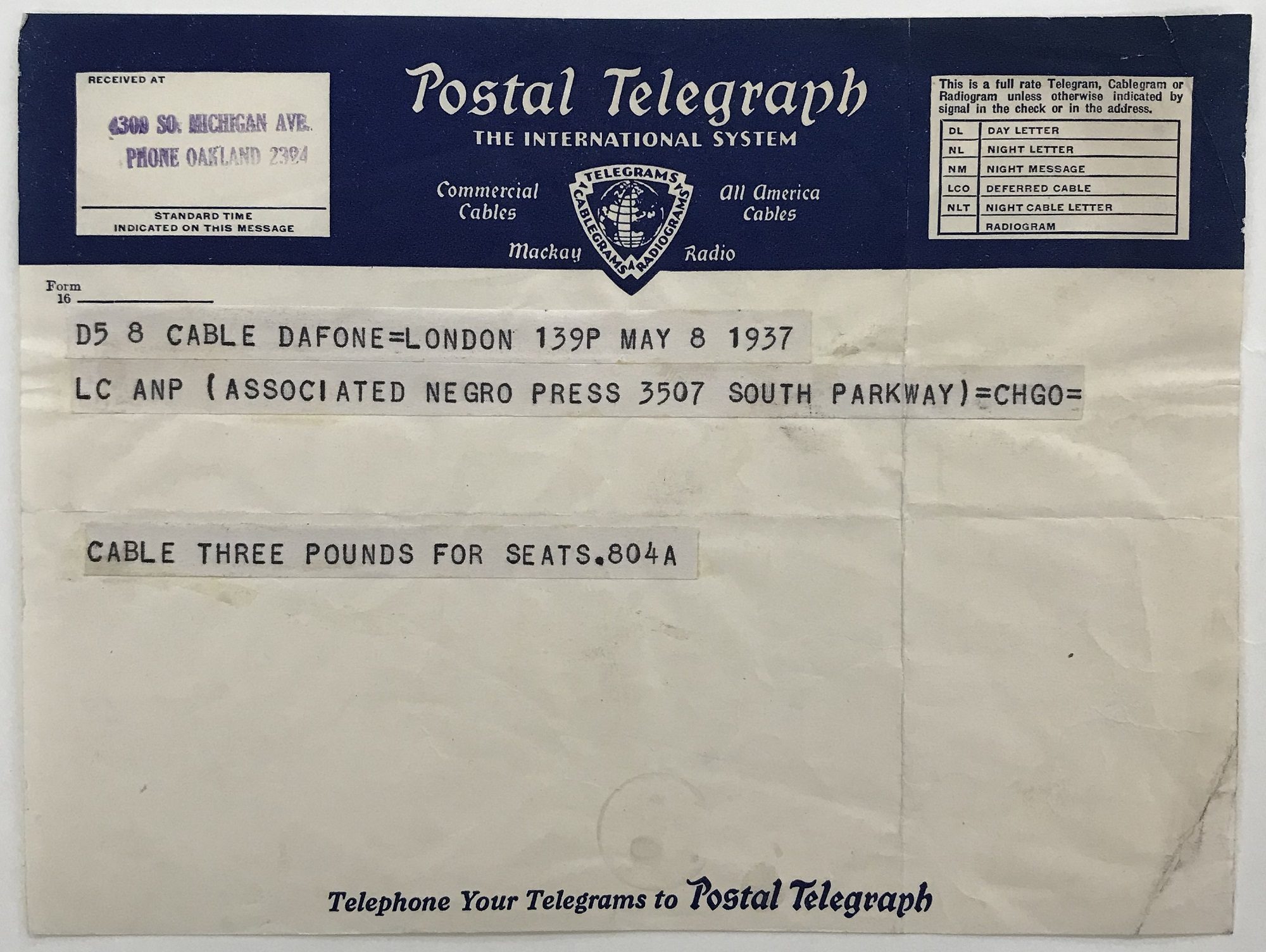

Photograph titled “The supreme moment of great solemnity: The crowning of the king by the Archbishop of Canterbury in Westminster Abbey.” The Illustrated London News, May 15, 1937, vol. 100, no. 2612. AP4.I3 FOLIO-B

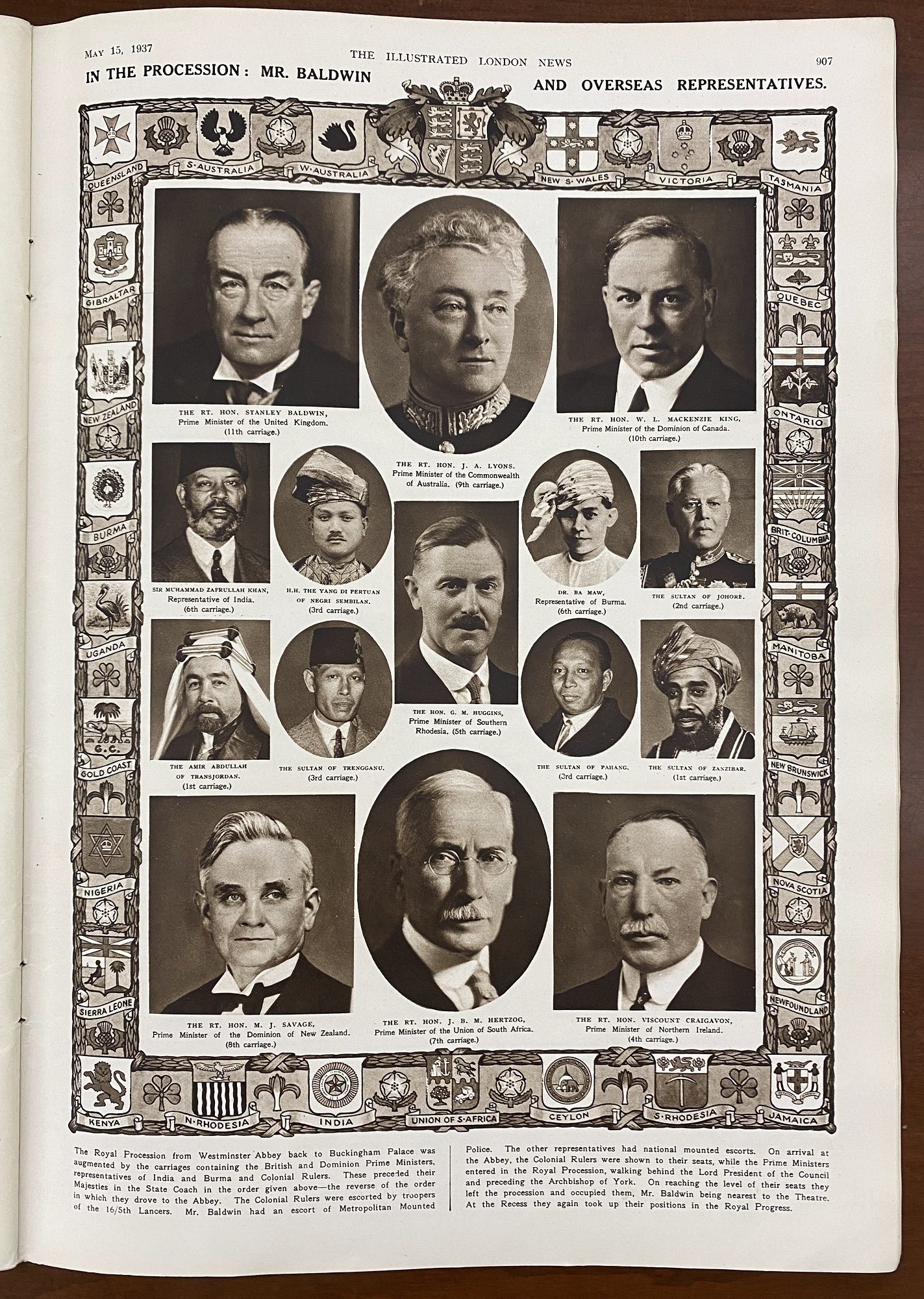

The ceremony leaned into the traditional precedence set by George V’s 1911 coronation with subtle nods to the shifting status of the role of the monarch amidst the Commonwealth. Additionally, the media played a more prominent role than ever before in a coronation ceremony.

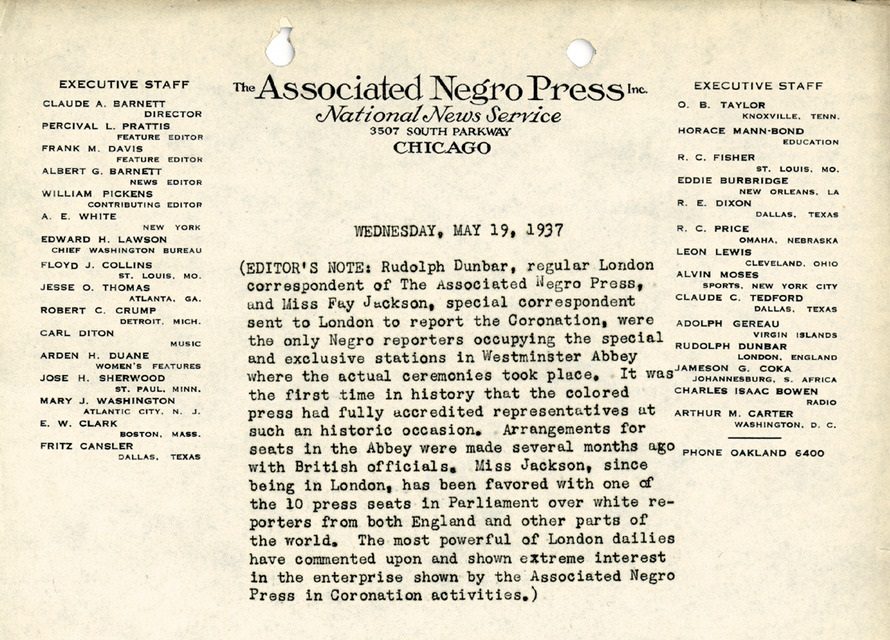

In Rudolph Dunbar’s dictum regarding the day of the coronation, his editor’s note states that he “and Miss Fay Jackson were the only Negro reporters occupying the special and exclusive stations in Westminster Abbey. It was the first time in history that the colored press had fully accredited representatives at such an historic occasion.”

The top half of a release regarding the coronation of King George VI, May 19, 1937. CHM, ICHi-068441

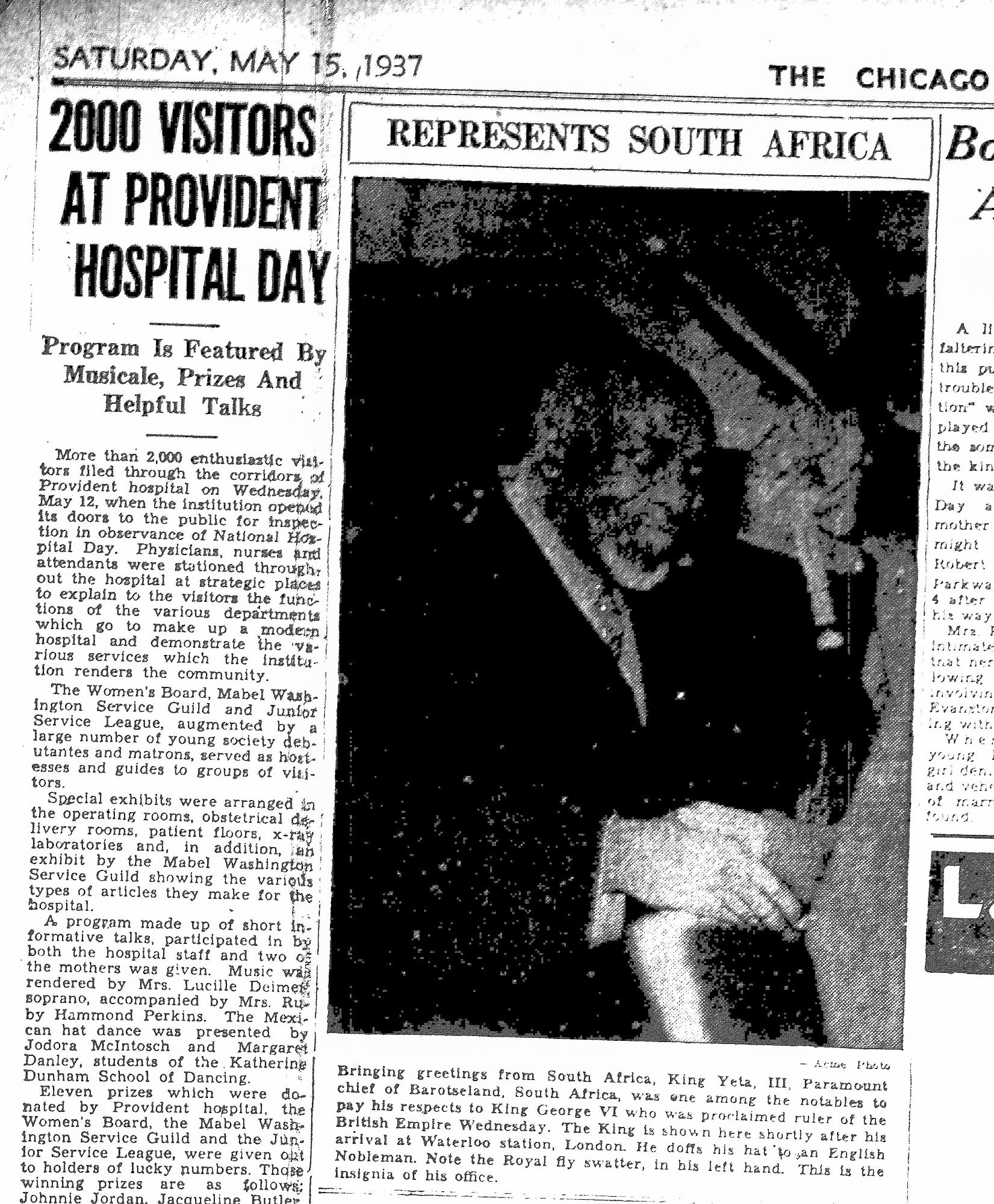

Jackson reported with a critical eye on not just what took place during but also obvious omissions to the coronation festivities. Her accounts recall how the African heads of state and Black dignitaries were treated unfairly. In one of her stories, she notes, “While 22 of the States and Mandated territories under His Majesty’s protection are black with a combined population of some 400 million, it may be clearly seen that nothing like the representation of blacks by black is here as, for instance, one notes among the Indians and other races . . . No Black Africans appear on the Royal Guest list. It will be recalled that the Chieftains were actually snubbed, originally, because the present King chose to follow the ‘precedent set down by his father, the late King George V.’ Two are here: Yeta III, Paramount Chief of Barotseland, and Ademola II, Alake of Abeokuta. They are included in the last as ‘distinguished visitors.’”

A photograph of King Yeta III, Paramount Chief of Barotseland, South Africa, arriving at Waterloo Station in London. He carries a fly swatter, the insignia of his office. Chicago Defender, Saturday, May 15, 1937, city edition.

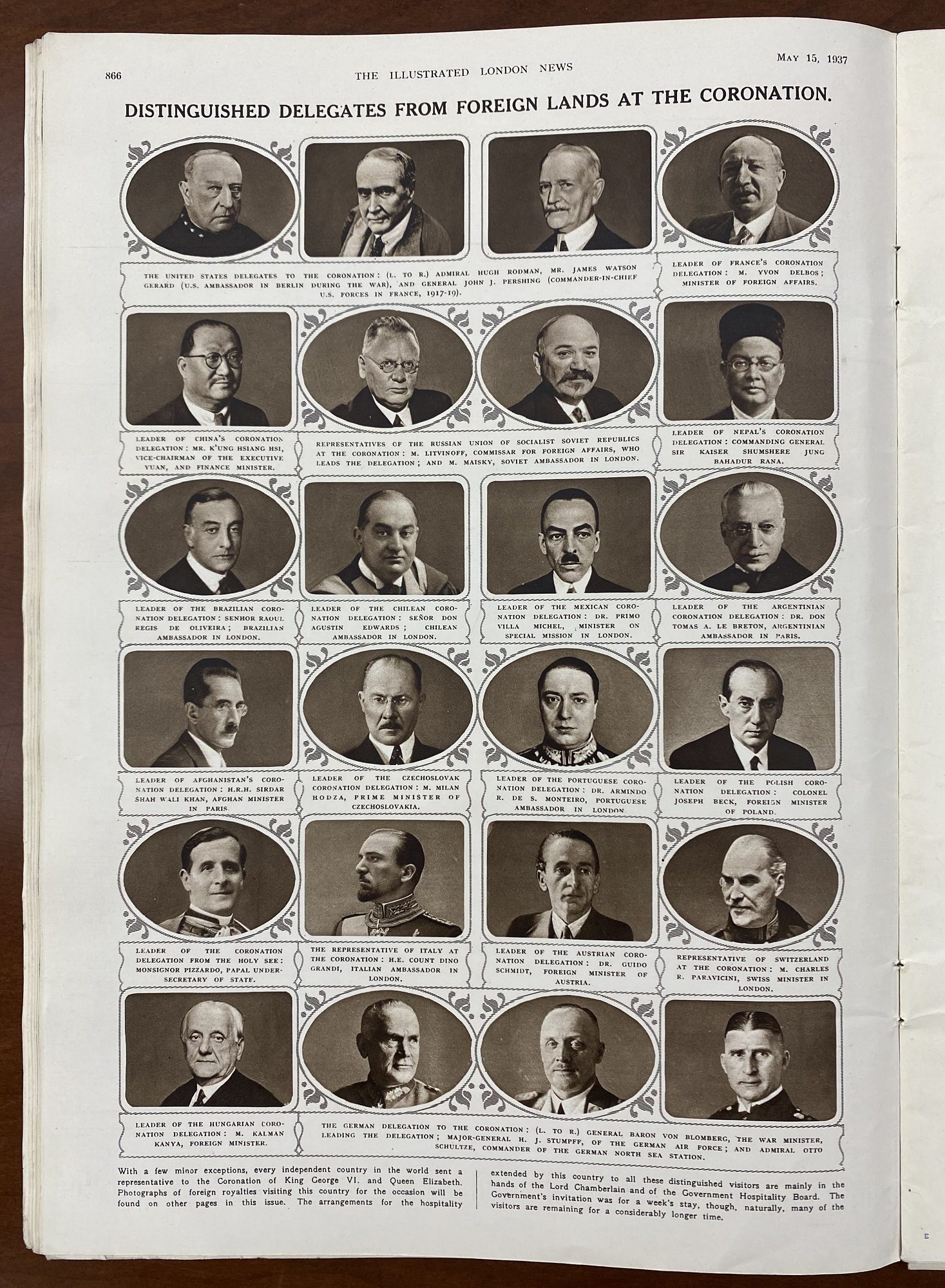

Another example of the omission of Black presence was the news coverage. In The Illustrated London News, the only African leaders pictured are the Sultan of Zanzibar and white colonial leaders such as J. B. M. Hertzog, and the only foreign delegates pictured hail from Europe, Asia, and the Americas.

The Illustrated London News, May 15, 1937, vol. 100, no. 2612. AP4.I3 FOLIO-B

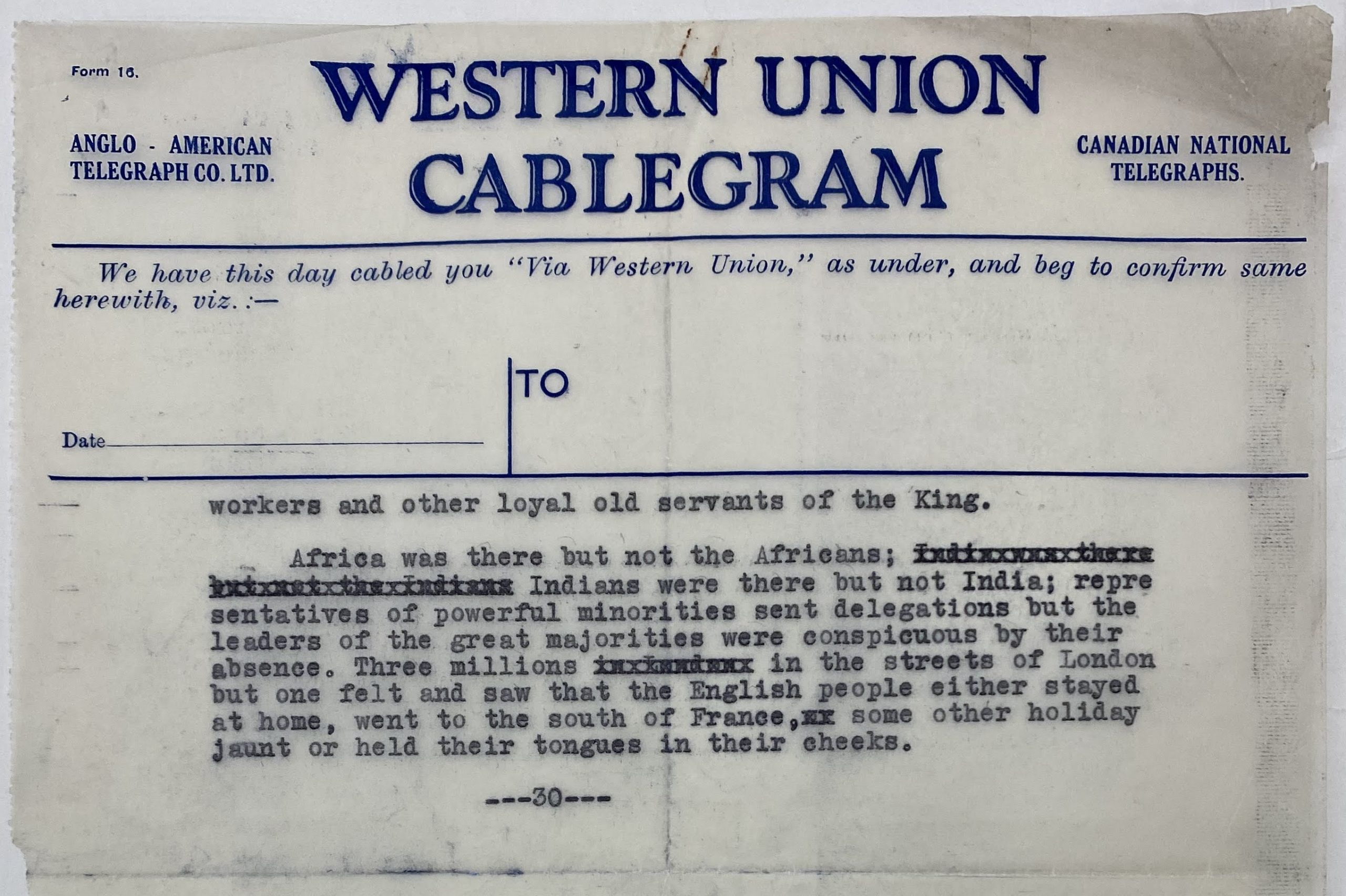

In a cablegram Jackson sent to the ANP on May 13, 1937, she relays her observations of how Black dignitaries were treated: “. . . the coronation procession of King George VI gave Africa the poorest showing of all the countries represented. Among thirty thousand troops from Canada, New Zealand, India, the Union of South Africa, Malay, the West Indies and other members of the Colonial and Protectorate territories, only 25 barefoot native blacks marched at the tailend [sic] of the colonial contingent but the applause that greeted them was rivaled only by the deafening accalamation [sic] given to the majestic Indians who completely stole the show, even from Britain’s Navy men . . . The King’s escort of officers from the Colonial contingents contained no black faces, and African representatives, or distinguished visitors were shunted into the rear of a stand facing Buckingham where they could see little of the procession.”

A cablegram from Jackson to Barnett, May, 13, 1937.

She continues with: “Africa was there but not the Africans; Indians were there but not India; representatives of powerful minorities sent delegations but the leaders of the great majorities were conspicuous by their absence.”

Fay Jackson’s reports were published in major Black newspapers in the US, including the California Eagle, and earned her praise. In a letter from Barnett to Jackson, he writes: “You have done a grand job and we are very proud of you. I suspect the acclaim to which the papers have hailed your exploit[s] and the personal appreciation which must be in the minds of thousands of folk throughout the country, will be some measure of compensation because, of course, our contribution is a mere mite outside of the channel of service in enabling you to do what you aspired to accomplish. It leaves you the No. 1 Negro newswoman anyway.”

Coauthored by CHM curator of religion and community history Rebekah Coffman and CHM content manager & editor Esther D. Wang.

Additional Resources

- Learn more about the Claude A. Barnett papers [manuscript], 1918–67, at the Abakanowicz Research Center, which is free to visit

- Read more about Fay Jackson’s reporting partner, Rudolph Dunbar, whose papers are housed at Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library