Katherine Quiroa is a graduate student at University of Illinois Chicago who interned with CHM curator of civic engagement and social justice Elena Gonzales for our upcoming exhibition Aquí en Chicago. Part of her work includes researching Latino/a/x histories of Chicago.

During the late 1910s, the Mexican population was growing in Chicago. The majority of Mexicans lived on the Near West Side, which is now home to neighborhoods like University Village, Little Italy, and Greektown. A century ago, the Near West Side, known as “the Valley,” was home to immigrants of predominantly Greek, Italian, and Jewish heritage who established themselves in the area in the nineteenth century. The Near West Side was also home to many African Americans who arrived in the 1930s. In 1917, this community continued to diversify as Mexicans, who migrated to the US as a result of World War I and the Mexican Revolution, settled on the Near West Side.

Settlement houses began developing in areas such as Chicago where urbanization, industrialization, and immigration were on the rise. In 1889, Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr founded the Hull-House social settlement. They envisioned a space where social services, entertainment, education, and more would aid the low-income immigrant population to establish roots in Chicago. By 1917, anchored by Hull-House, the Near West Side was home to Chicago’s first Mexican barrio on the intersections of Harrison and Halsted streets; the neighborhood was home to more than 7,000 Mexicans. Mexican immigrants who arrived after the war made use of the services and amenities Hull-House provided, easing their adjustment to Chicago.

Exterior of the Hull House after its relocation to the University of Illinois Circle campus and four-year remodeling and restoration project, 800 South Halsted Street, Chicago, June 2, 1967. ST-13001698-0002, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Although the Near West Side was a low-income neighborhood, residents had created a vibrant, diverse, and well-established community. From 1949 to 1961, the city was constructing the Eisenhower Expressway in hopes of easing traffic while simultaneously redeveloping impoverished residential neighborhoods like Near West Side which displaced many residents who were either pushed out by construction or could not afford to live in the area. The highway displaced roughly “13,000 people and forced out more than 400 businesses in Chicago alone.”

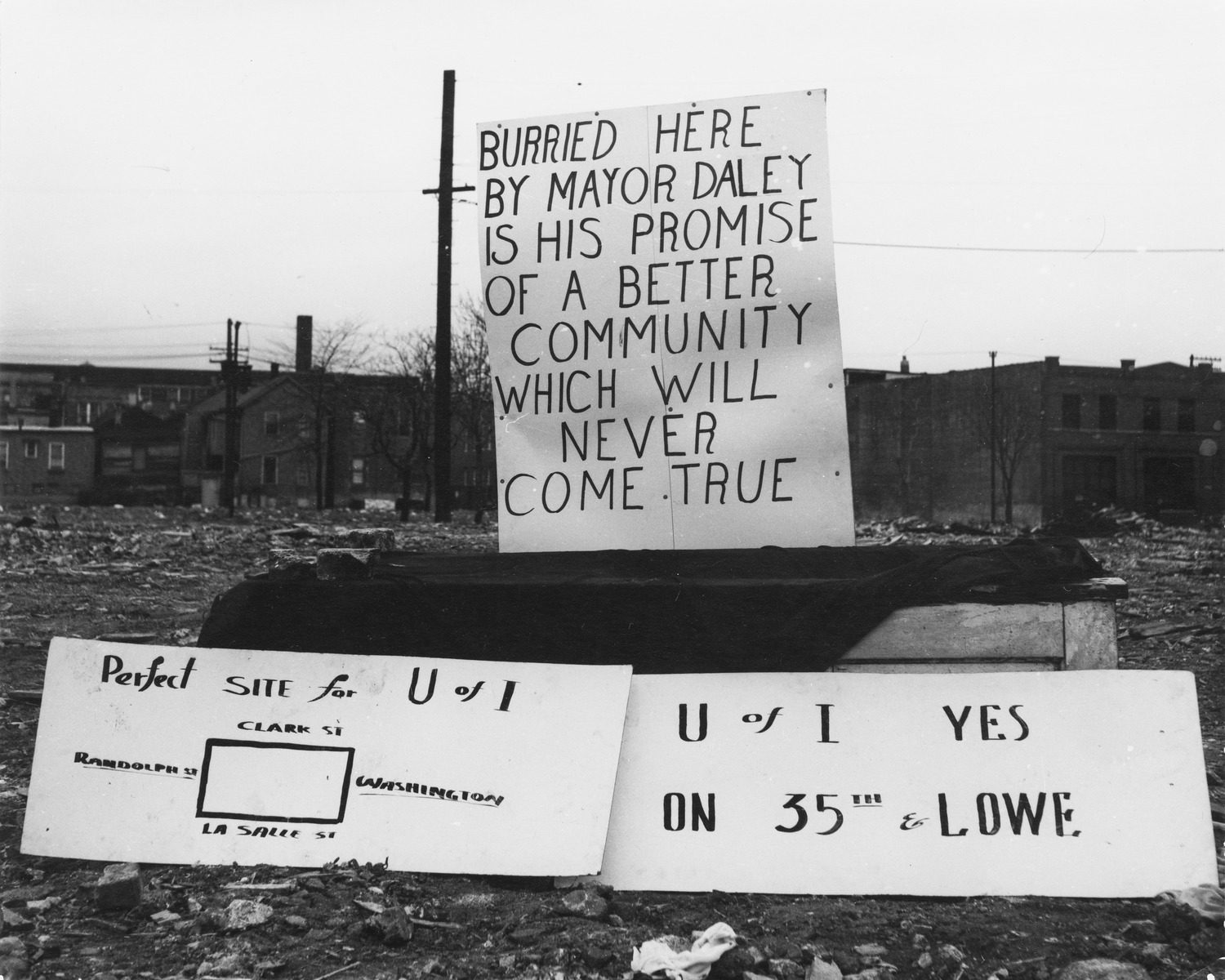

At the same time, the University of Illinois Chicago campus on Navy Pier became congested by an overwhelming number of students who eventually protested for their campus to be relocated. Mayor Daley discreetly proposed that the Harrison-Halsted site be the new location for the University of Illinois Chicago Circle (UICC) campus which had been accepted by the University Board. The site was convenient for urban developers and officials as the land had been declared a site for urban renewal. Many Chicagoans heavily criticized the Department of Urban Renewal for failing to keep their word to the Near West Side residents when they claimed they “would improve the community, and the first priority would be the residents.”

Vacant property (razed for future building) and signs in Harrison and Halsted Streets area, Chicago, August 1962. One sign reads: Burried [sic] here by Mayor Daley is his promise of a better community which will never come true. CHM, ICHi-014396; Larry E. Hemenway, photographer

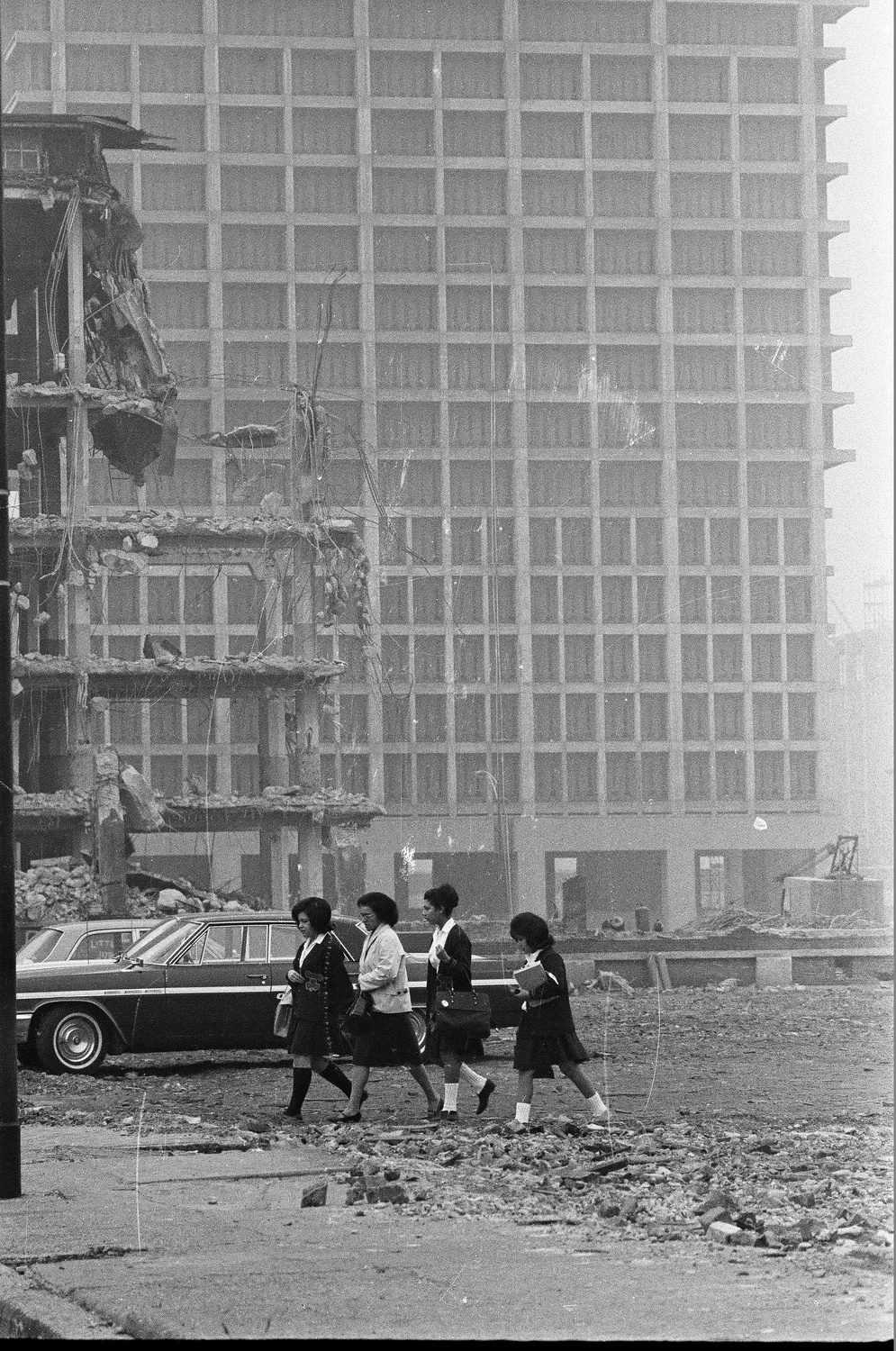

Residents rejected displacement by UICC, protesting for their right to remain in their homes. Ultimately, the Chicago City Council and UICC are responsible for the dislocation of the Near West Side community. UIC’s Circle campus came at the expense of 8,000 residents and 640 businesses (Siczek 2020). The specific intersection of Harrison and Halsted was home to a large Mexican community that had established itself over the course of 40 years.

This post will specifically focus on the Mexican population in the Near West Side, Hull-House services that aided their adjustment into the community, and their housing displacement stemming from the creation of the UICC campus.

Hull-House

Hull-House ensured access to cultural programs, English classes, clinics, and support from the Immigrant Protective League which would ensure a smooth transition for Mexican immigrants. The large Mexican population was able to find jobs in manufacturing, health care, railroad track laborers, and also within Hull House itself. The arts program at Hull-House fostered a creative expression amongst its participants who told their stories through art, especially pottery. Many of the Mexican residents were ceramicists in Mexico and found an opportunity to share their expertise with others. Eventually, the Hull-House Kilns opened avenues of income through pottery.

Jesús Torres, from Guanajuato, Mexico, immigrated to the US with his wife to find seasonal employment opportunities to make ends meet. Eventually they found themselves on the Near West Side where Jesús took a passionate and eventually professional interest in ceramics. Adrian Lozano was another professional artist who emerged from the Hull-House arts program. Lozano painted the first Mexican mural in Chicago and later went on to design the Mexican Fine Arts Center Museum expansion (now National Museum of Mexican Art), Benito Juarez High School, and the Little Village Arch, the first Chicago Landmark by a Mexican architect. Unfortunately, Lozano’s mural was buried under the rubble when UICC began construction.

Installation Photo from Jane Addams Hull-House Museum, photo by Elena Gonzales

Resistance and Politics

The creation of UICC’s campus targeted young men and wealthy suburban students who would attend the University, but also frequent local businesses owned by the same. This caused controversy as the University would not only displace a large community, but it would also redirect business from locals to University-owned shops. The Chicago Sun-Times echoed the Mexican community’s criticisms of the University and city officials, claiming that “the project failed its announced intentions and has systematically forced the poor, long-time residents out of the neighborhood.”

With threats of being uprooted, several members of the Mexican community joined forces with the other European community members to form the Harrison-Halsted Community Group. They often congregated in Hull-House. Florence Scala, an activist, was born and raised on the Near West Side where she became to be known as the “root and flower” of the neighborhood for her activist efforts and contributions. Scala’s background in urban renewal and city planning would aid her in leading the Harrison-Halsted Community Group, composed of Near West Side residents, in protests against the city and the University.

Residents gather in front of Guardian Angel School, 717 West Arthington Street, for a march on the city hall to protest the site of the new University of Illinois campus at Harrison Street and Halsted Street, Chicago, February 14, 1961. The site was originally slated for a housing development. ST-17600009, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

On October 9, 1962, several members of the Harrison-Halsted Community Group began a sit-in at Mayor Daley’s outer office which lasted several days. The objective of the sit-in was to “halt legal actions against property owners” until a judge could rule the project unconstitutional. The group was eventually removed from the outer office without an answer.

Exterior view of a neighborhood around the Near West Side, around West Monroe Street and South Paulina Street, Chicago, Illinois, November 10, 1964. ST-15001686-0004, Chicago Sun-Times collection, Chicago History Museum

Other government officials such as the US District Court Judge James B. Parson had disregarded the cries and claims of Near West Side residents by claiming that “community groups have no legal right to resist changes in the community if the changes promote the general welfare”. Rachel Cardero, resident of the Near West Side and member of the Community for United Latinas, expressed the organization’s frustrations to the media by posing the question, “If we were good enough to live here when the place was a slum, why are we being forced out now that the neighborhood has been rehabilitated?”

Aftermath

As the construction of the campus displaced residents of the Near West Side, another neighborhood changed as well: the growing Mexican neighborhood of Pilsen, located just south and east of the Near West Side. In the 1940s and 50s Pilsen was already home to the large Mexican community from the Near West Side that the Eisenhower Expressway had displaced. Now, thousands more displaced Latinxs joined them.

Despite UIC’s initial plans to attract wealthy Anglo students, the University has become a Hispanic Serving Institution (HSI). From 1971 to 1976, there was an increase in student-led mobilization against the University for underrepresenting its Latinx student population. These students, faculty, and political actors carried the mobilizations that demanded that the University include “education and justice for people of color” in their curriculum (University of Illinois Chicago). Eventually, the University underwent academic changes in the 70s that catered to its Latinx students in response to the protests. However, creating educational programs, support services, and celebrations of the arts does not compensate for the displacement of former Latinxs residents.

The tragic consequences of dislocation that Near West Side residents highlight the lack of planning and consideration that officials had when establishing UICC in the area. Although it is too late to reverse the actions of the University and city officials, the Near West Side can serve as an example for urban developers and universities who are looking to establish institutions. Thoughtful planning and consideration is required to avoid repeating the story of the Near West Side.