In 1980, a Chicago steel mill called Wisconsin Steel Works, large enough to take up most of South Deering, a community area on the city’s far South Side, closed its doors forever. Ownership of the mill had recently been sold by International Harvester, who had been using the mill for their farm equipment, to a very new company called Envirodyne, which had no experience in the industry. When their poor management led to the mill abruptly closing, however, it was the mill’s thousands of employees who dealt with the consequences. In honor of Labor Day, we’ll be looking at the history of how Chicago’s steel workers organized and cared for one another throughout the twentieth century, whether that be in a union, caucus, or autonomously.

When it originally opened in 1875, the mill was the Joseph H. Brown Iron and Steel Company. It became Wisconsin Steel Works under International Harvester in 1902. This letter W sign is from the Wisconsin Steel Works mill. CHM, ICHi-066079. In CHM’s Museum Collection, 2000.68.2.

Since steel mills first opened in the late nineteenth century, working in them has been a difficult and dangerous job. Steelworkers work with heavy machinery, fire, and molten metal. In an oral history interview for the Southeast Chicago Historical Society, Osborne Ferguson, who worked at the Acme Steel Plant from 1964 to 2001 said that the first day he went into the mill with just a shirt and pants on, the heat was so intense that he went and ate his lunch outside on the steps.

These steel-toed boots were owned and used by Herbert H. Post, a civil engineer, who worked at US Steel South Works from 1948 to 1977, designed to protect him both from the mill temperatures that could go above 110 degrees Fahrenheit as well as the heavy machinery he worked with. CHM, ICHi-040640_view01. In CHM’s Museum Collection, 2000.116.2a-b.

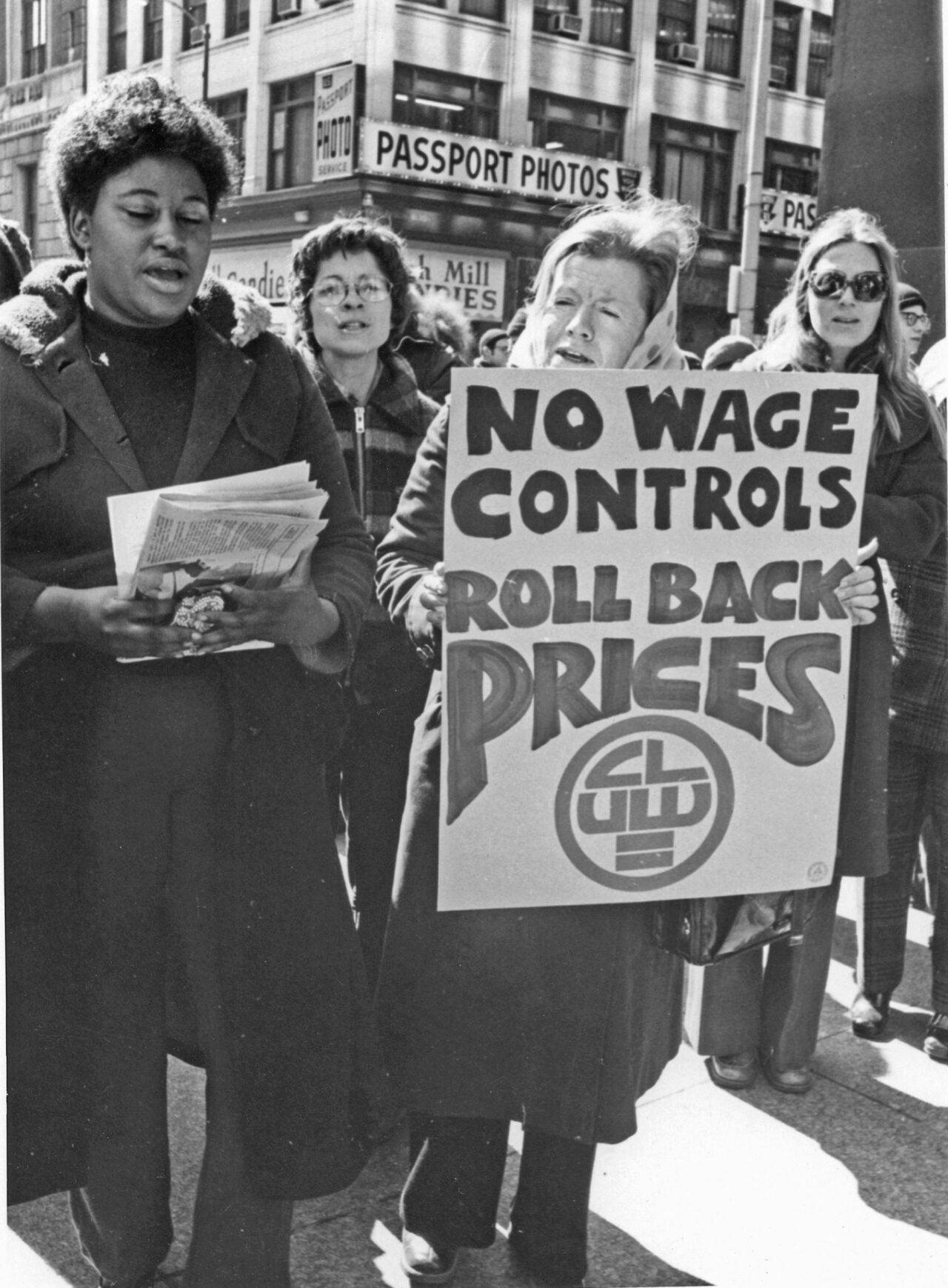

These jobs still drew in many people because of the community and the union benefits. In an interview for the Studs Terkel Center for Oral History, Roberta Wood, a steelworker, activist, and communist, described how she and lots of women began working in the steel mills after 1974 when organized African American workers fought for equal hiring rights across racial and gender lines. They found that they had many issues in common, like inadequate bathrooms, workplace harassment, and a lack of representation in their union leadership. Together, they formed a women’s caucus across multiple steel mills in the Chicago and Northwest Indiana area. As a result, they not only began to make gains for women in steel mills, but also were able to win leadership positions in the United Steelworkers union and create a community that Wood describes as a place they could be in community with and in support of one another.

This photograph was taken in 1985 at an outside gathering of some of the Save Our Jobs Committee members, including Juanita Andrade and Frank Lumpkin and others. CHM, ICHi-031930.

While the sense of community counted for a lot, the benefits like the pension plan, unemployment benefits, and insurance that the union had fought hard for also gave steelworkers the ability to provide for themselves and their families. These mill jobs were not easy to get other work with, as their skills were not easily translatable to a different industry, which made it all the more difficult for the workers of Wisconsin Steel Works when it abruptly closed in 1980. Neither International Harvester nor Envirodyne would give them the benefits or even the last cycle of pay that they were owed. So, one of the workers at the mill, Frank Lumpkin, worked with a group of former steelworkers to form the Save Our Jobs (SOJ) Committee, which organized demonstrations and legal work to get the mill reopened. When that became impossible, they turned to organizing to get the benefits owed to them. Eventually, they won their court settlements, which saved many people’s homes and lives.

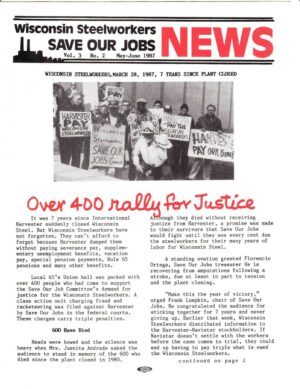

This is the front page of a newsletter issued by the Wisconsin Steelworkers Save Our Jobs Committee in 1987, reporting on a rally of over 400 people in support of the committee and the workers’ class action lawsuit to regain their benefits. It also recognizes the mourning and memory of the 600 former workers who had died within the seven years since the mill had closed. Wisconsin Steelworkers Save Our Jobs News, Vol. 3, No. 2, March 28, 1987. Southeast Chicago Historical Society Digital Archive, FIC-0000-054.

However, SOJ meetings and actions also served as a vital social support system for the unemployed steelworkers who faced isolation, depression, and rising cases of suicide. The SOJ cared for one another and recognized the struggles of their fellow workers, so they put on dinners and other events to make sure people were kept in their support. Chicago’s story of the SOJ shows that workers can organize and win in many different circumstances, and this year on Labor Day we should remember that community and solidarity go hand in hand in the fight for workers’ rights.

About the Author

Dan Murrieta worked this summer as a collections intern at the Swedish American Museum. He is an undergraduate student at Northwestern University studying History, Literature, and Latin American and Caribbean Studies.

Additional Resources

- Frank and Beatrice Lumpkin Papers at CHM’s Abakanowicz Research Center

- Chicago Cold War: Beatrice Lumpkin Oral History Interview

- Chicago Cold War: Roberta Wood Oral History Interview

- The HistoryMakers biography of Frank Lumpkin

- “Always Bring a Crowd”: The Story of Frank Lumpkin, Steelworker

- Resources from the Southeast Chicago Archive & Storytelling Project

- “The Closing of the Mills” web documentary

- Interview with Frank Lumpkin during Save Our Jobs Committee March

- Save Our Jobs Committee March and Meeting video

- Wisconsin Steelworkers Save Our Jobs News, Vol. 4, No. 2

- Wisconsin Steelworkers Save Our Jobs News, Vol. 3, No. 2

- Save Our Jobs Committee, Justice For Wisconsin Steelworkers panel discussion video

- Save Our Jobs Committee, Outside Wisconsin Steel Works photograph

- Tribute to Frank Lumpkin, Save Our Jobs video