This summer Ina Cox worked on the Chicago History Museum’s latest collaborative initiative, the North Lawndale History Project, developed by Paul Norrington, president and founder of the K-Town Historic District Association, Inc. She was the Senior North Lawndale Minow Fellow working with Peter T. Alter, the Museum’s historian and director of the Studs Terkel Center for Oral History. This is the fourth post in a series about the project.

As I look back on this summer, reflecting on the time Wynton, Zilah, Peter, and I have spent working together, one feeling stands out: the work is just getting started. Before the project got underway, we assessed the popular narrative about North Lawndale to get a sense of where we were starting. I read The American Millstone: An Examination of the Nation’s Permanent Underclass (1986), the Chicago Tribune’s notoriously problematic depiction of the community as a “permanent underclass.”

I asked Zilah and Wynton to report on the information universe surrounding North Lawndale by exploring its representation in a variety of databases—everything from the Chicago Public Library Special Collections to Twitter—so that we could assess the tone and quality of the public narrative. After only twenty-seven working days, our team successfully added six oral histories to the historical record about North Lawndale community activism and leadership.

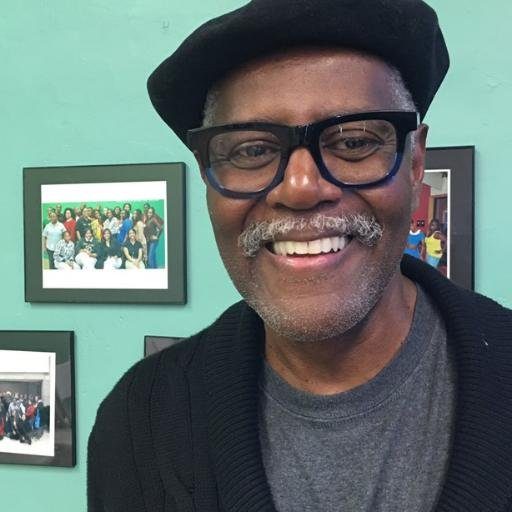

From left: Zilah Harris, Audrey Dunford, Wynton Alexander, and Ina Cox, 2017. Photograph by Paul Norrington

If you’re not familiar with the work of oral history, you might not think that six is much at all. But, when done right, the process is painstaking. We had to find willing narrators who have significant life experiences and connections to North Lawndale. Then, we had to secure a time and place for each interview. Once we established that, we conducted substantial historical research and familiarized ourselves with the narrator’s background. We drafted questions, interviewed the individual, and archived it.

We were a veritable oral history factory this summer. I am very proud of what we accomplished—particularly of the growth of Zilah and Wynton into budding young oral historians! I came into this position with research and writing skills. I am leaving with a newfound appreciation for the centrality of interpersonal relationships in public history work. For that I am grateful to Peter, Wynton, and Zilah for teaching me what mentorship is all about.

And yet, there is still so much that remains to be done. I don’t think any of us believed that we could archive a comprehensive portrait of North Lawndale—or imagined that such a thing would even be possible. Once you start on a project like this, you can’t help but see the holes that exist and the needs that remain unaddressed. Almost every narrator spoke to the hope that telling North Lawndale’s story would make it a better place.

They agreed to be interviewed because they understand the power of storytelling, the narratives that become history. And in all of them we could sense the yearning for a brighter future if only by encouraging others to see the neighborhood through a different lens. Beyond the issues that plague the community, North Lawndale suffers from a reputational problem. Public history, particularly oral history, helps by telling the story over again.

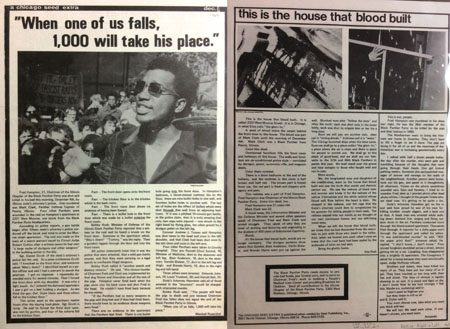

Blanche Suggs-Killingsworth, 2017. Photograph by Ina Cox

Listen to Blanche Suggs-Killingsworth of Neighborhood Housing Services and the North Lawndale Historical and Cultural Society talk about what it means to serve North Lawndale and her perspective on what Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination meant for her community.

Hear Audrey Dunford of the North Lawndale Restorative Justice Community Court talk about how imprisonment often results from her community being misunderstood.