CHM curatorial intern Brigid Kennedy recounts the extraordinary life of Mary Livermore. This blog post is part of a series in which we share the stories of local women who made history in anticipation of CHM’s upcoming exhibition Democracy Limited: Chicago Women and the Vote.

Mary Livermore dedicated her life to abolition, temperance, women’s suffrage, and supporting the Union during the Civil War. Skilled in organizing, raising awareness, and gaining support for her causes, Livermore became a friend to Abraham Lincoln, a popular orator, and a key figure in the Union’s victory.

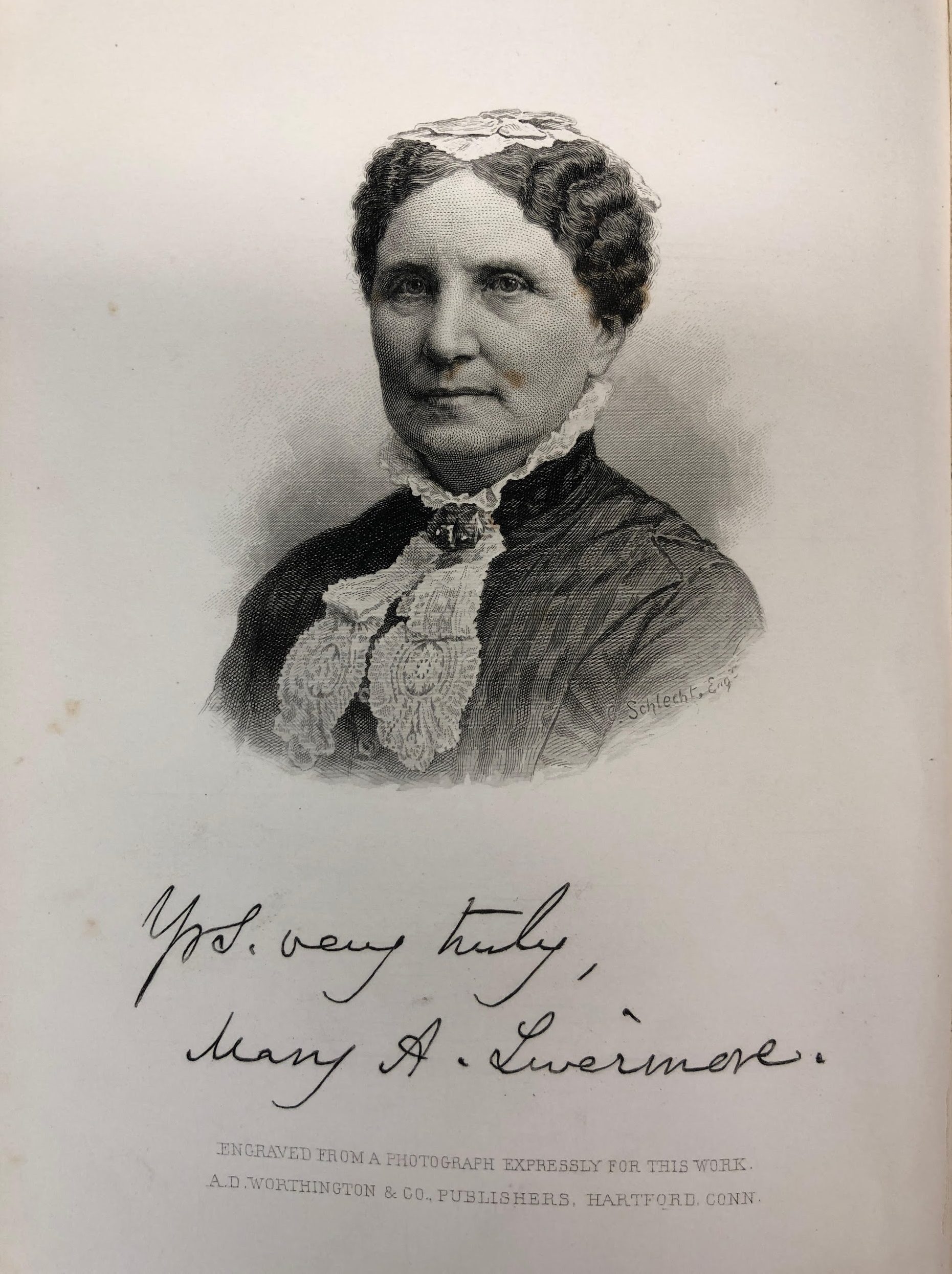

An undated portrait of Mary A. Livermore. ICHi-051132, CHM

Born in Boston on December 19, 1820, Livermore spent her early years there working in a secondary school—even editing a temperance newspaper for young people.

Livermore, her husband Daniel, and their family planned to move to Kansas in 1857 with other abolitionists, intending to secure Kansas as a free state. Before the move was complete, their daughter became sick and the family decided to settle in Chicago.

Livermore quickly established herself as a philanthropist in the rapidly growing city. She cofounded the Home for the Friendless, Home for Aged Women, and the Hospital for Women and Children in her first six years in the city. Then, the Civil War broke out.

In June 1861, it became clear that the Union Army was suffering more from illness and malnutrition than from Confederate weaponry, and Lincoln established the United States Sanitary Commission to centralize civilian relief efforts. A Chicago branch opened soon after, managed by Livermore and Jane Hoge. Livermore toured Union encampments and battlefront hospitals, delivering supplies, attending to the wounded, and bringing back news from the front.

In early 1863, Ulysses S. Grant praised the Sanitary Commission and credited them with saving many lives. Still, Grant’s needs were beyond what the Commission could provide as his army closed in on Vicksburg, Mississippi, and he requested more aid.

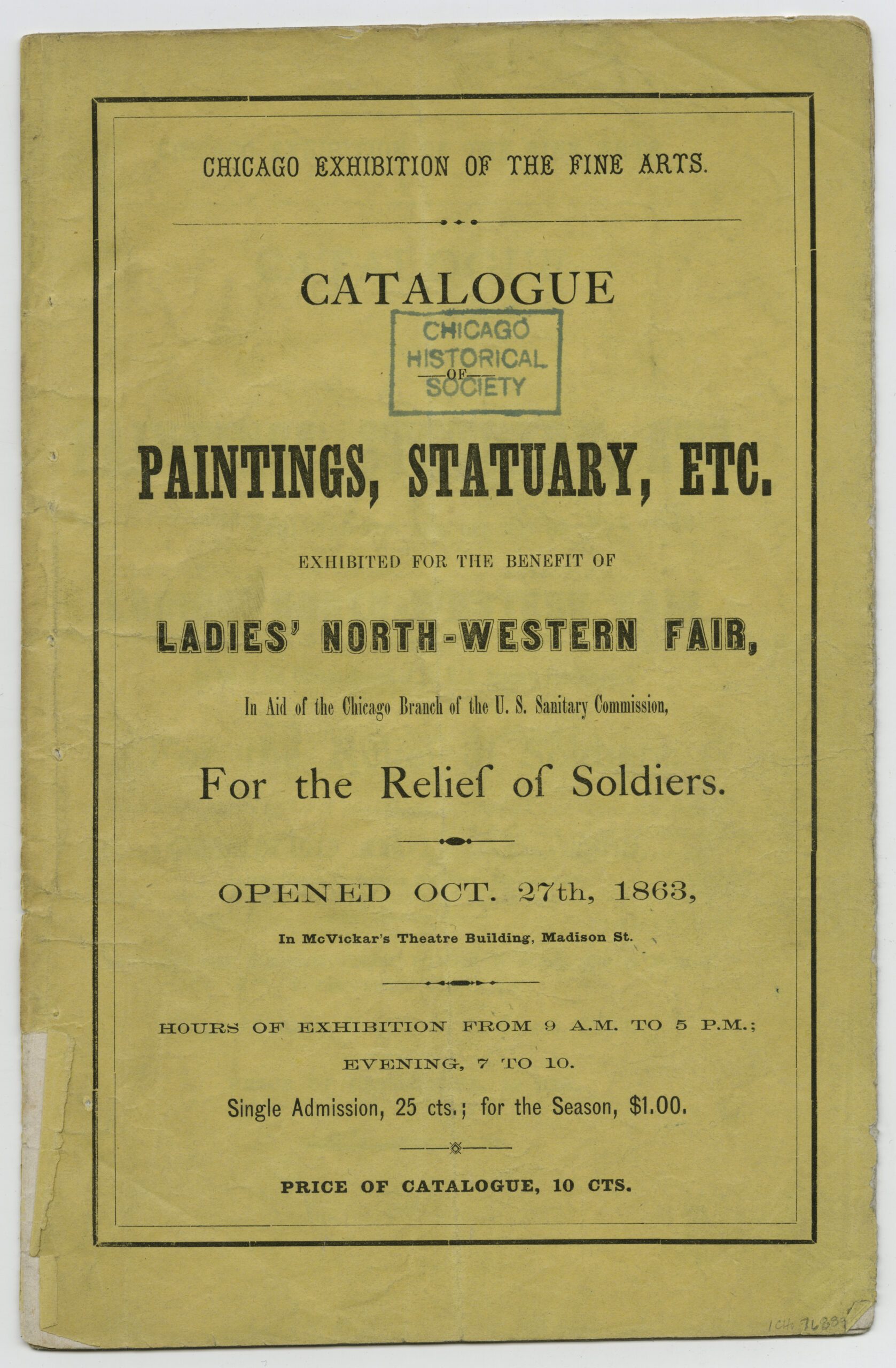

Front cover of Catalogue of Paintings, Statuary, Etc. exhibited for the benefit of the Great Northwestern Fair, 1863. ICHi-076889, CHM

Livermore and Hoge proposed a Great Northwestern Fair, where they could auction off or sell food, entertainment, and mementos of the war. They recruited thousands of volunteers, almost all women, to plan the event—the first of its kind.

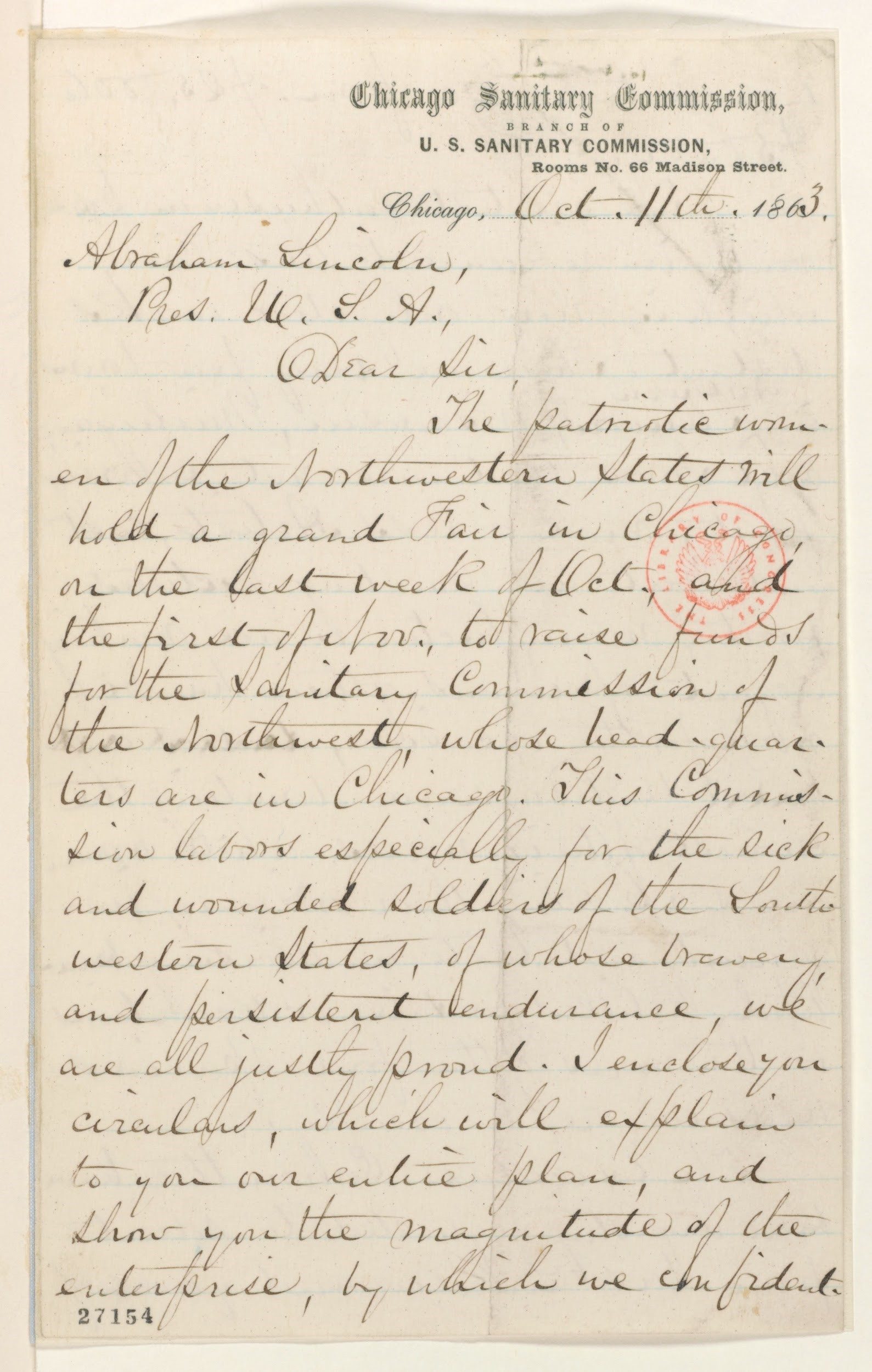

Livermore acquired war mementos for auction from across the Midwest, and even requested assistance from Abraham Lincoln, who donated the original Emancipation Proclamation. It sold for $10,000 and found a home at the Chicago Historical Society before being destroyed by the Great Fire in 1871.

On October 11, 1863, Livermore wrote to Lincoln requesting the original copy of the Emancipation Proclamation. Abraham Lincoln papers at the Library of Congress: series 1, General Correspondence 1833–1916.

The 1863 Great Northwestern Fair was a resounding success. Livermore had hoped to earn at least $25,000, and in the end, the Sanitary Commission made more than $86,000 from the estimated eighty-five to ninety thousand visitors. The fair fundraising model became popular, and soon similar events were held in other American cities.

Due to the success of the 1863 Great Northwestern Sanitary Fair, a second fair was held in 1865. ICHi-063123, CHM

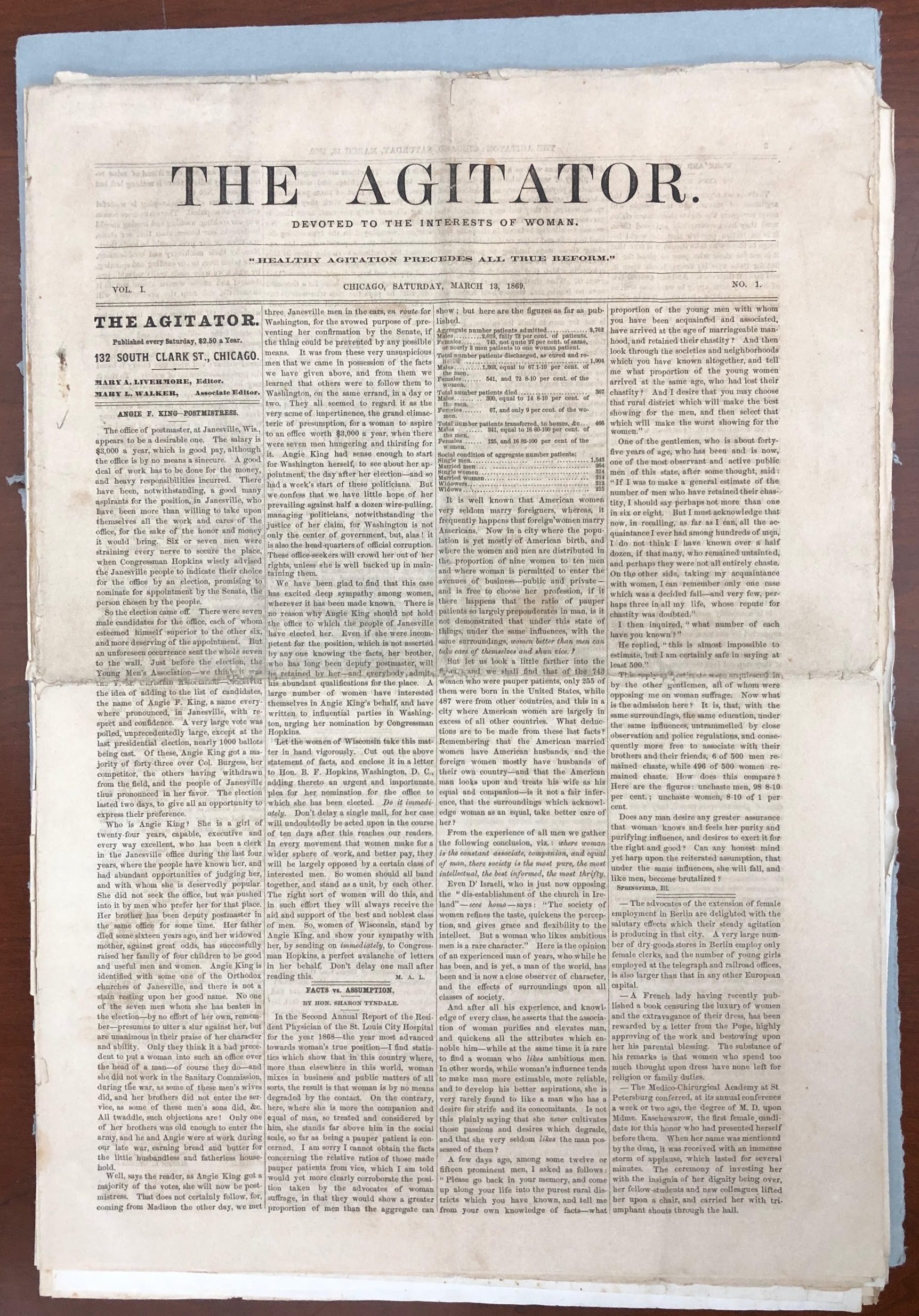

After the war, Livermore focused her energy on fighting for women’s suffrage. In 1869, she organized Chicago’s first suffrage convention and established The Agitator, a suffrage newspaper.

March 13, 1869, edition of The Agitator, with the subheading “Healthy agitation precedes all true reform.” The Agitator, CHM

In 1870, Livermore returned to Massachusetts, but continued her work in Chicago from afar. She traveled the country, lecturing on the history, lives, and experiences of women. She wrote two autobiographies and other texts supporting the rights of women.

An autographed page from one of Livermore’s autobiographies, “My Story of the War: A Woman’s Narrative of Four Years’ Personal Experience in the Sanitary Service of the Rebellion,” 1888. CHM

Although Mary Livermore didn’t plan to spend such a large portion of her life in Chicago, the life she built here not only made her instrumental to the Union war effort, but also made the day-to-day lives of many Chicagoans—especially women—safer through her philanthropic and activist work.