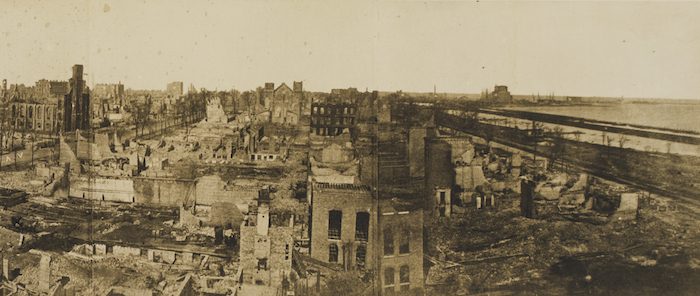

On this day in 1871, a fire began on DeKoven Street in a barn owned by Catherine and Patrick O’Leary. Fueled by a gale-force wind, this blaze grew into the Great Chicago Fire. Advancing northward over three days, the inferno destroyed three and a half square miles in the heart of the city, leveling more than 18,000 structures. One-third of the city’s 300,000 residents lost their homes, and at least 300 perished. As devastating as it was, the disaster provided the young city with new opportunities and a chance for renewal.

Chicago rebuilt so quickly that within four years, there were no traces of the fire to be seen. Due to insurance companies and city governments mandating fire-resistant construction, architects began experimenting with steel, and by 1885, the Home Insurance Building, the world’s first modern skyscraper, was completed. By 1890, Chicago’s population tripled to one million and was selected by the US House of Representatives to host the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition.

So, how have catastrophes shaped and even improved modern city life? For the October 2020 issue of The Atlantic, CHM assistant curator Julius L. Jones spoke to Derek Thompson about the Great Chicago Fire within the content of how calamities can force us to question the physical and societal structures around us, break down the political and regulatory barriers to progress, and attract the funding and talent that can solve big problems and spur technological leaps. Read the article.