CHM curator of religion and community history Rebekah Coffman talks about the significance of Passover and shares a brief history of Chicago’s Jewish communities.

Sundown on Wednesday, April 5, 2023, marks the beginning of the Jewish holiday of Pesach or Passover. Celebrated by the Jewish diaspora for eight days, it is a time to remember the biblical story of Moses leading the Israelites out of slavery in Egypt. Also known as the Feast of Unleavened Bread, Passover is remembered through removing all chametz (yeast) from one’s home and not eating anything yeast-leavened for the days of remembrance as a form of sacrifice and a representation of removing sin from one’s life.

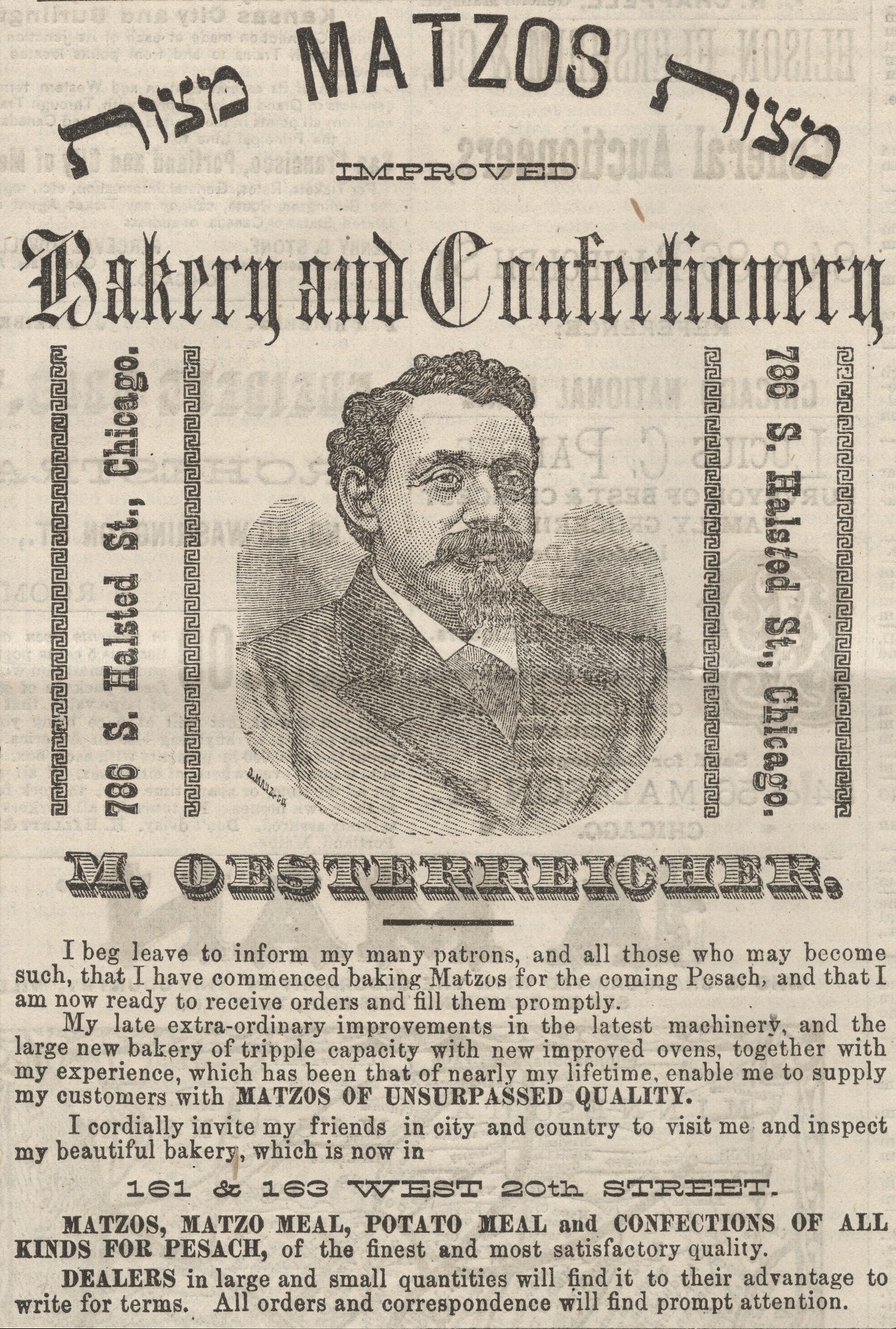

Left: Advertisement for M. Oesterreicher Bakery and Confectionery at 786 S. Halsted St. from The Occident Newspaper, 1885. CHM, ICHi-067038. Right: Advertisement for the Wittenberg Matzoh Co. at 1326 S. Jefferson St., from The Sentinel Newspaper, March 18, 1937.

Another important part of the tradition is the Passover seder meal. Jewish families gather and ritually retell the story of the Exodus from Egypt through eating symbolic foods and drinks and reading from a text known as the Haggadah.

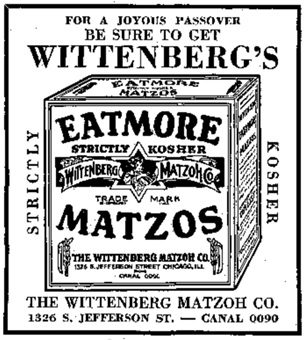

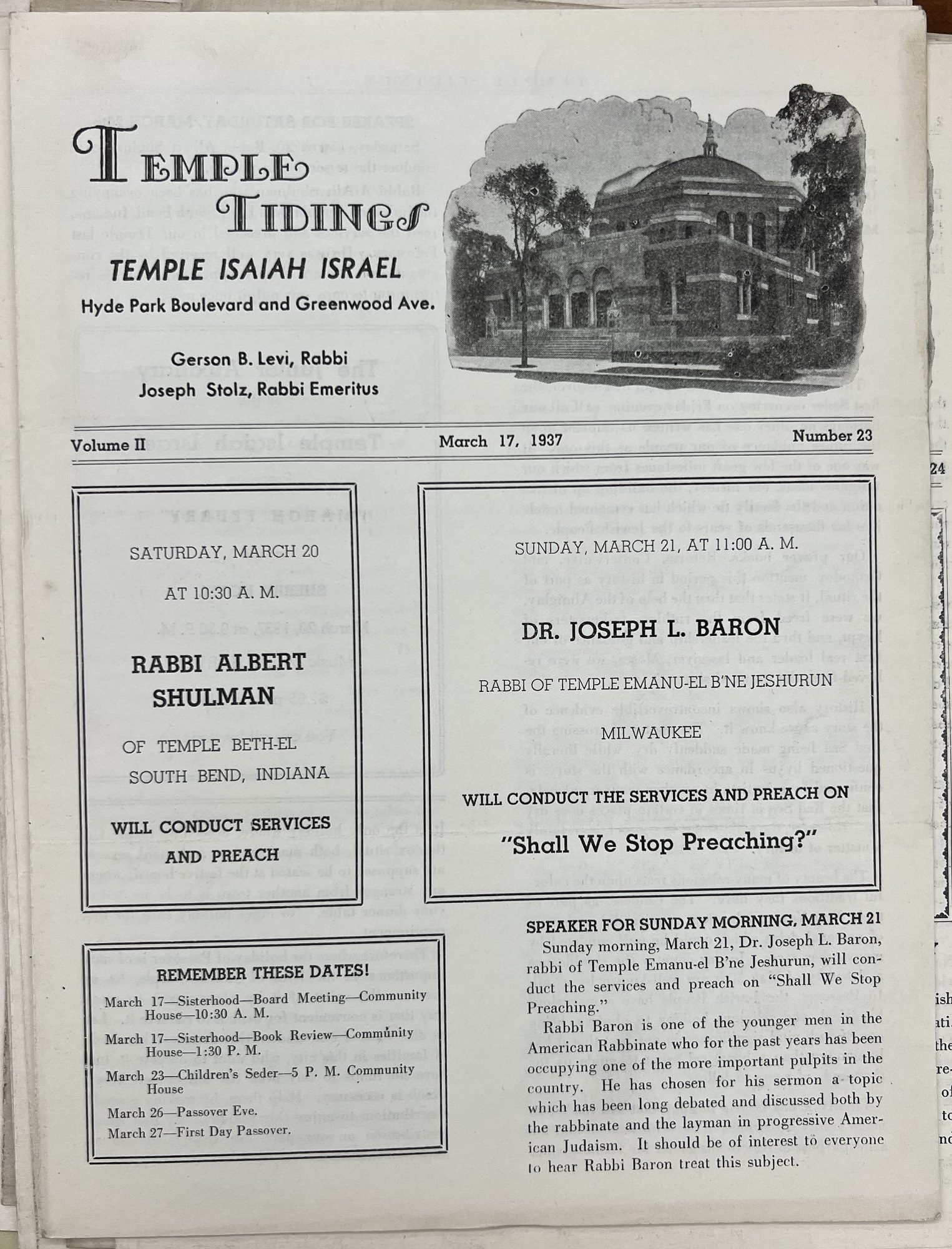

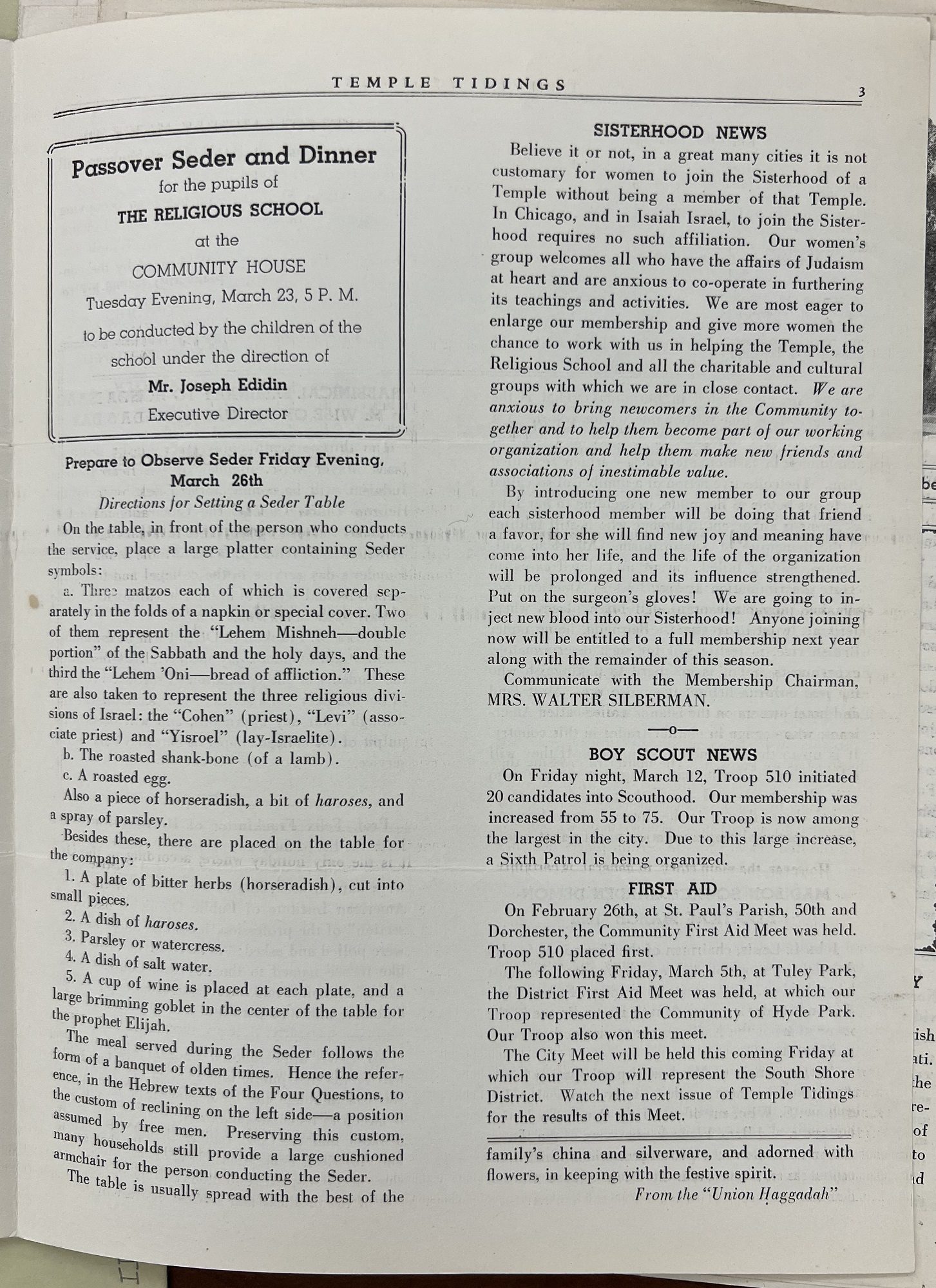

Two editions of Temple Isaiah Israel’s Temple Tidings, March 1937. From MSS Lot K.A.M. Isaiah Israel, CHM collection.

These 1937 congregational bulletins from Temple Isaiah Israel share the meaning of Passover and the Seder meal as part of their Passover editions of Temple Tidings. Inside the March 17 edition is a description of the elements needed for a seder and instructions for community members on the proper ways to prepare the table in remembrance. One of the central foods of Passover is matzah (plural matzos), a specific type of flat bread made of just flour and water, that is eaten in place of yeasted bread at every meal.

March 17, 1937, edition of Temple Isaiah Israel’s Temple Tidings. From MSS Lot K.A.M. Isaiah Israel, CHM collection.

As the bulletin describes, three matzos are included at the seder meal on a large platter, known as a seder plate, along with a shank bone, a roasted egg, horseradish, haroses (a mixture of fruits, nuts, and spices), parsley, and salt water. Each of these foods is eaten at specified times as the Haggadah is read, and they are accompanied by drinking four symbolic glasses of wine.

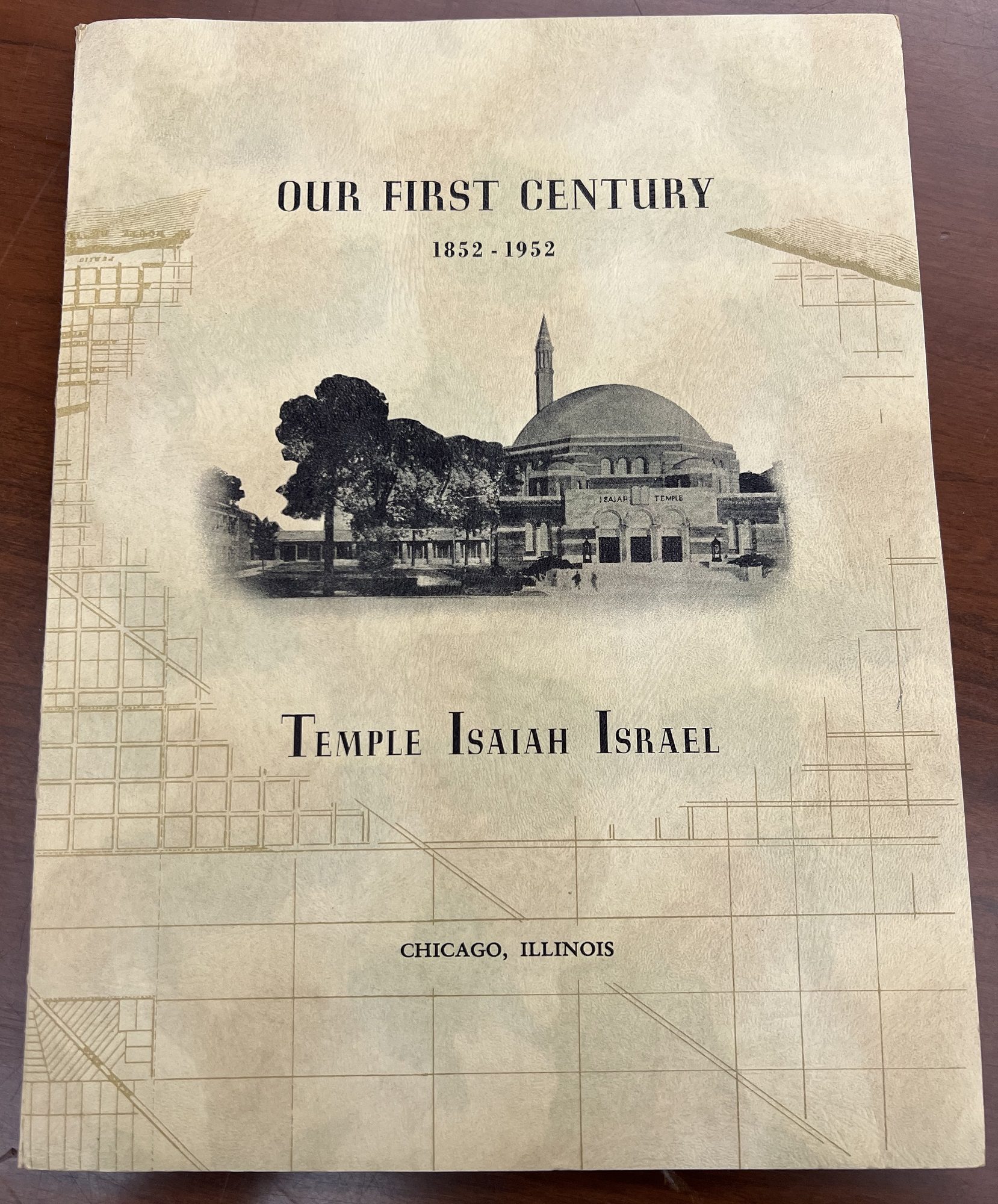

Commemorative book written by Rabbi M. M. Berman at the centennial celebration of Temple Isaiah Israel (B’nai Sholom), 1952. CHM Research Collection, F38W .Y-I7 1952 OVERSIZE

Temple Isaiah Israel’s congregational history demonstrates some of the many shifts, changes, mergers, and migrations that have defined Chicago’s Jewish communities. Jewish migration to Chicago began in the 1830s, with the first permanent Jewish families settling in 1841. The earliest synagogue in Chicago, Kehilath Anshe Maariv (Congregation of the Men of the West) (KAM), was founded in 1847 and led by German Jews who leaned Reform in their form of religious practice.

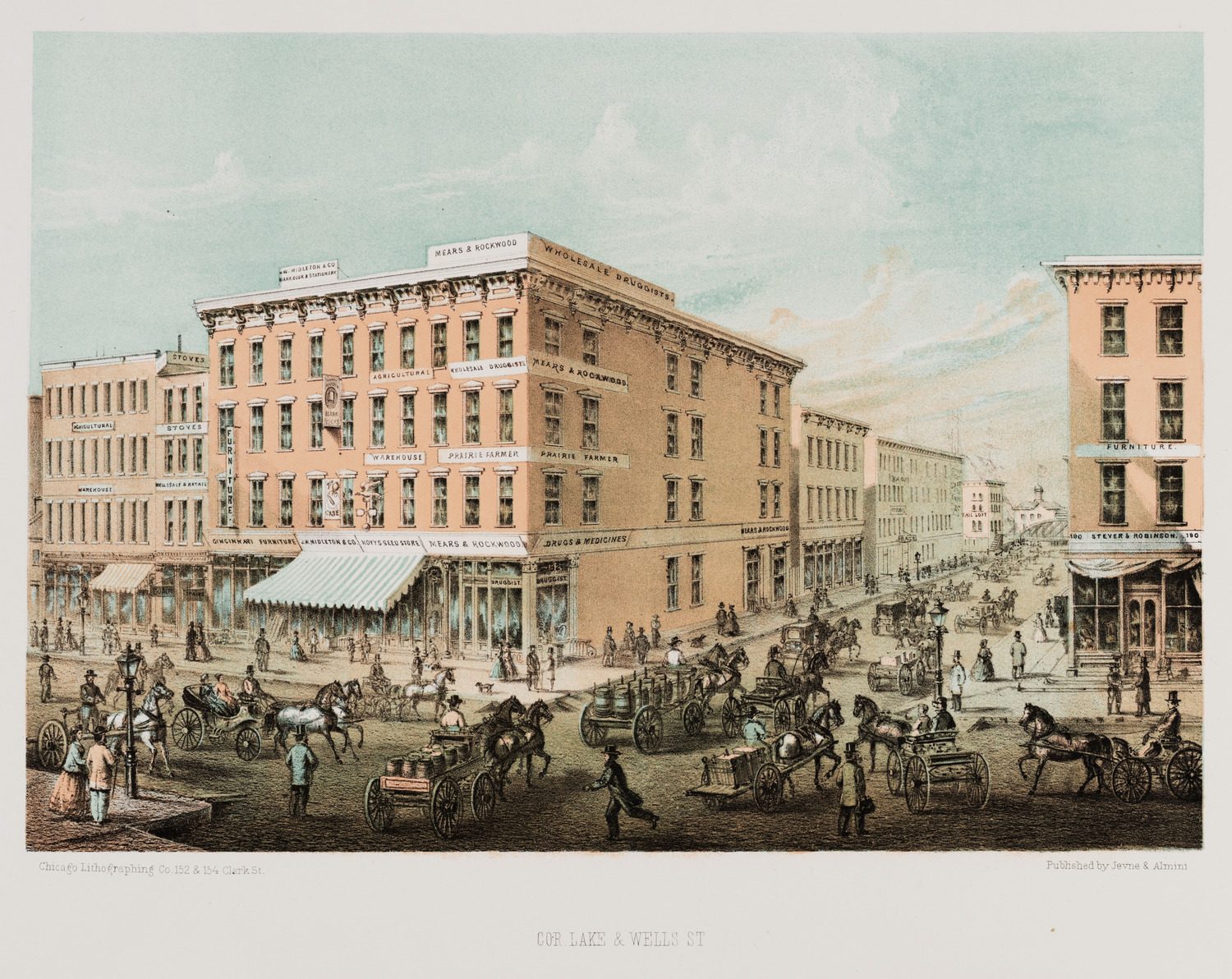

Intersection of Lake and Wells Streets, near the first meeting place for B’nai Sholom, c. 1867; lithograph by Jevne and Almini. CHM, ICHi-040005

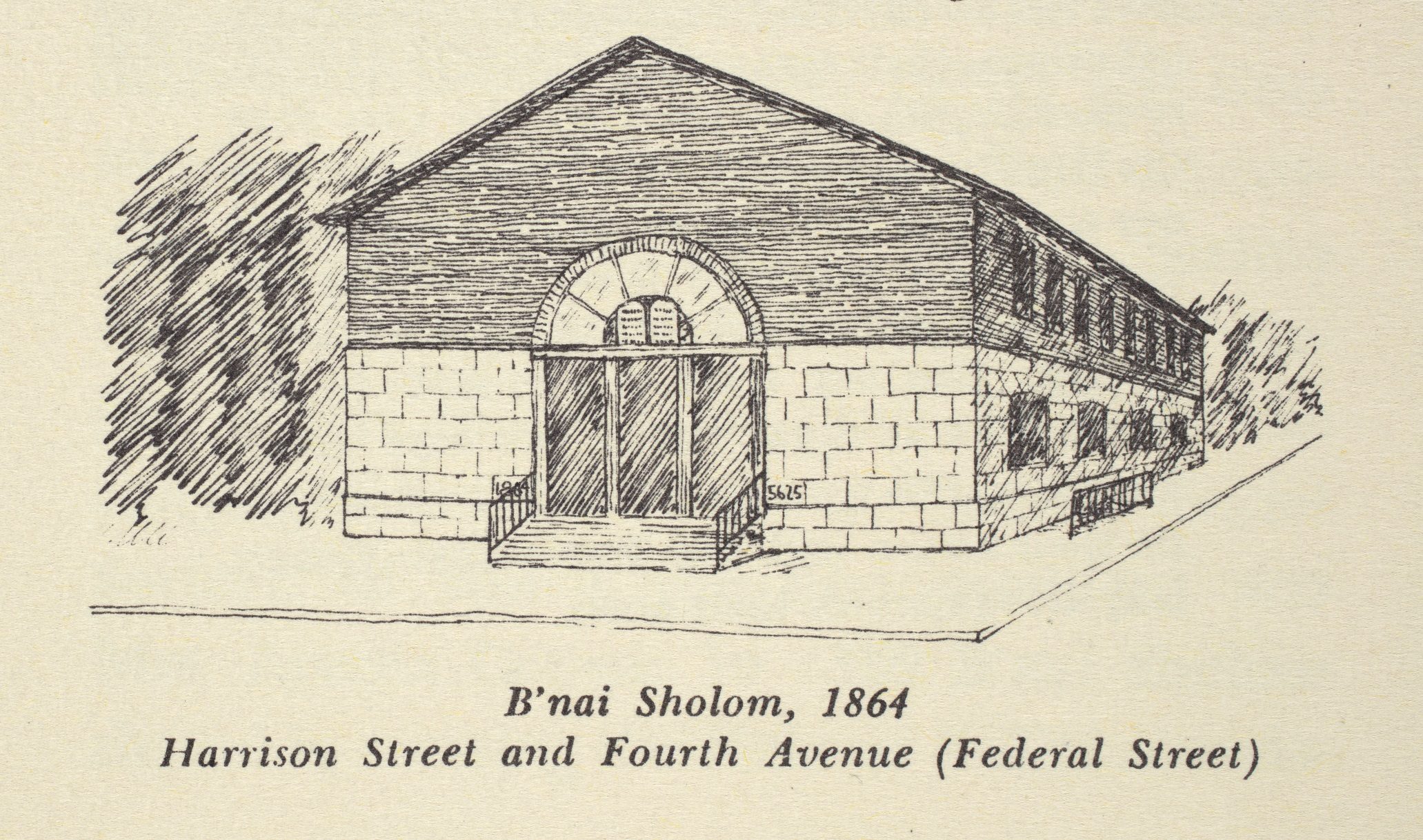

Just five years later, Chicago’s second-oldest congregation was organized by former KAM community members who identified as Polish Jews and leaned more Orthodox in practice. Calling themselves Kehilath B’nai Sholom (Congregation of the Children of Peace), they first met above a clothing store at 189 Lake Street, followed by a couple other temporary locations, before laying the cornerstone of their first building at Harrison Street and Fourth Avenue in 1864.

Architectural drawing of the exterior of B’nai Sholom, 1864. From Our First Century, 1852–1952: Temple Isaiah Israel, the United Congregations of B’nai Sholom, Temple Israel and Isaiah Temple, p. 14. CHM, ICHi-173824A

After losing this building to the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, B’nai Sholom briefly rented a church to hold worship before building a new synagogue on Michigan Avenue between Fourteenth and Fifteenth Streets. Before long, they outgrew this building and moved in 1886 to one formerly owned by KAM.

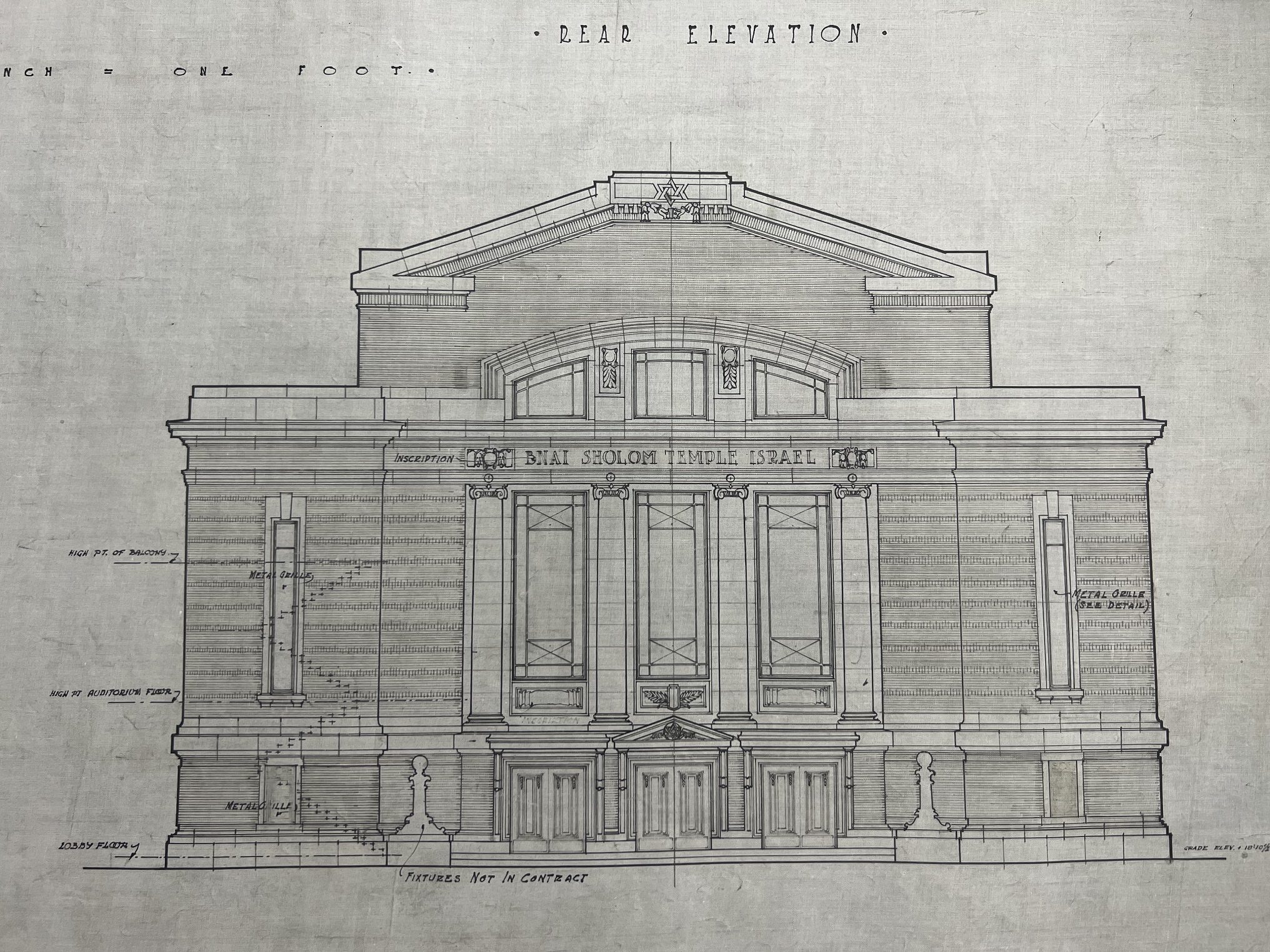

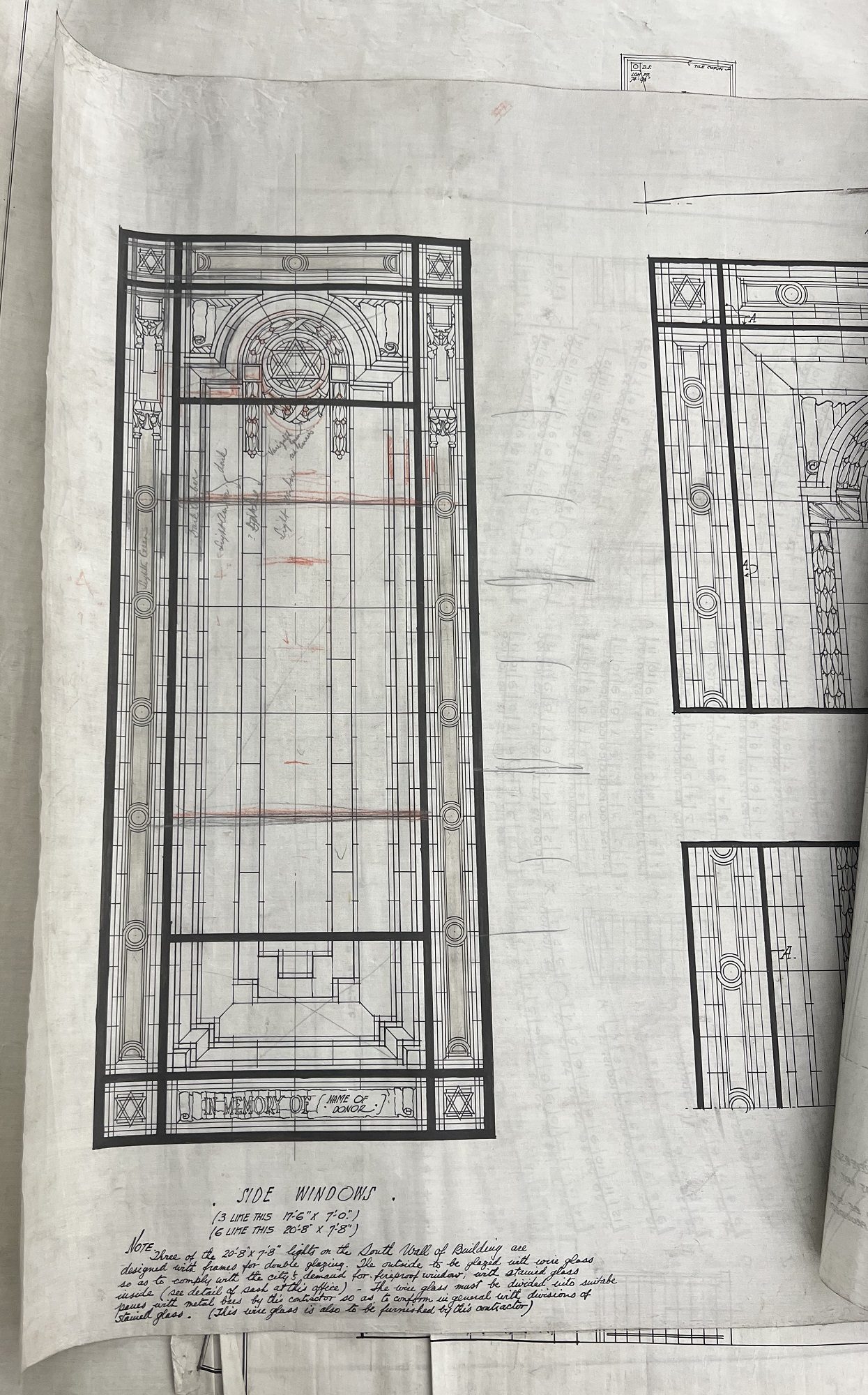

Architectural drawing details for B’nai Sholom Temple Israel by Alfred S. Alschuler, April 1, 1913. CHM collection. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman

Architectural drawing details for B’nai Sholom Temple Israel by Alfred S. Alschuler, April 1, 1913. CHM collection. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman

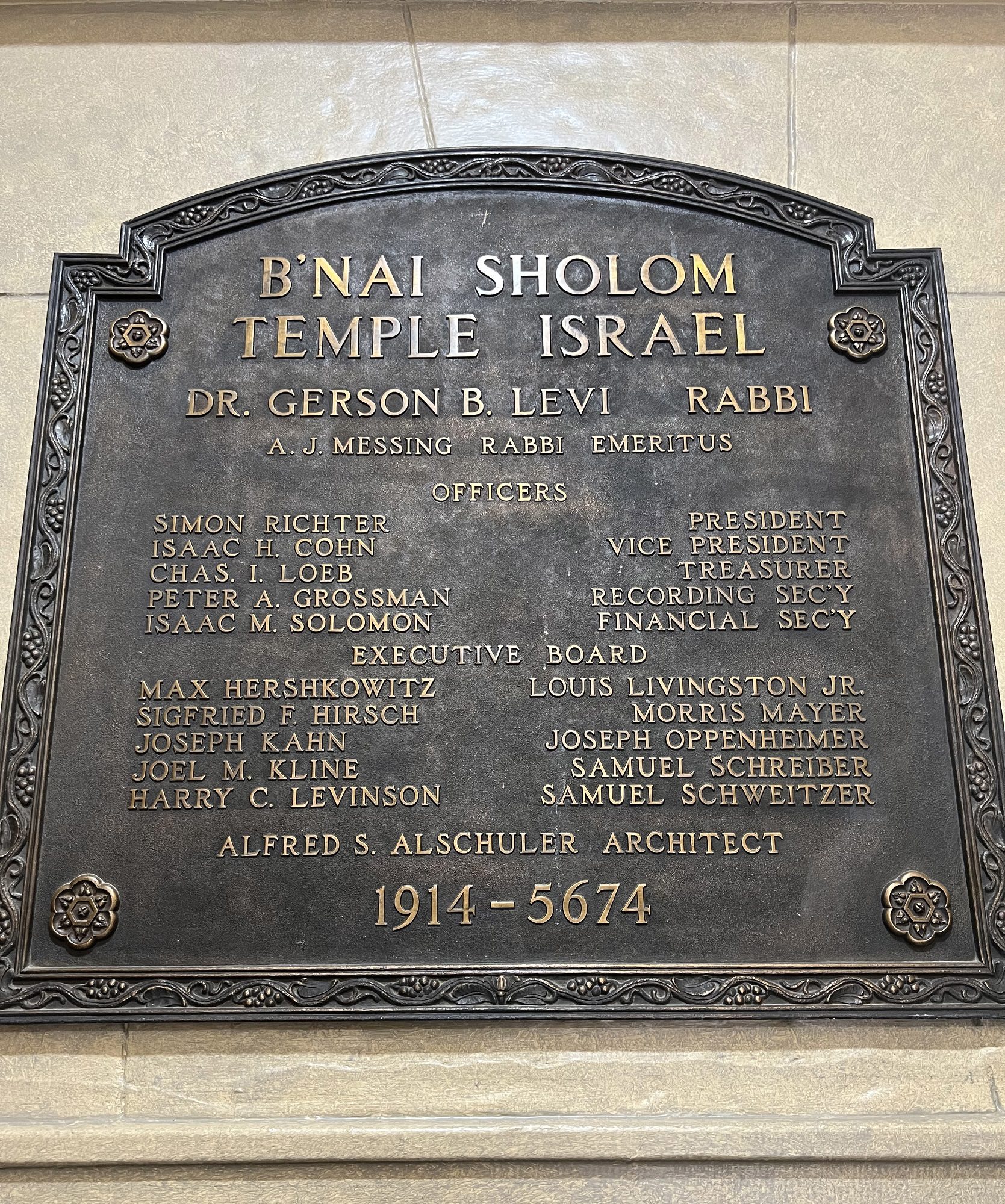

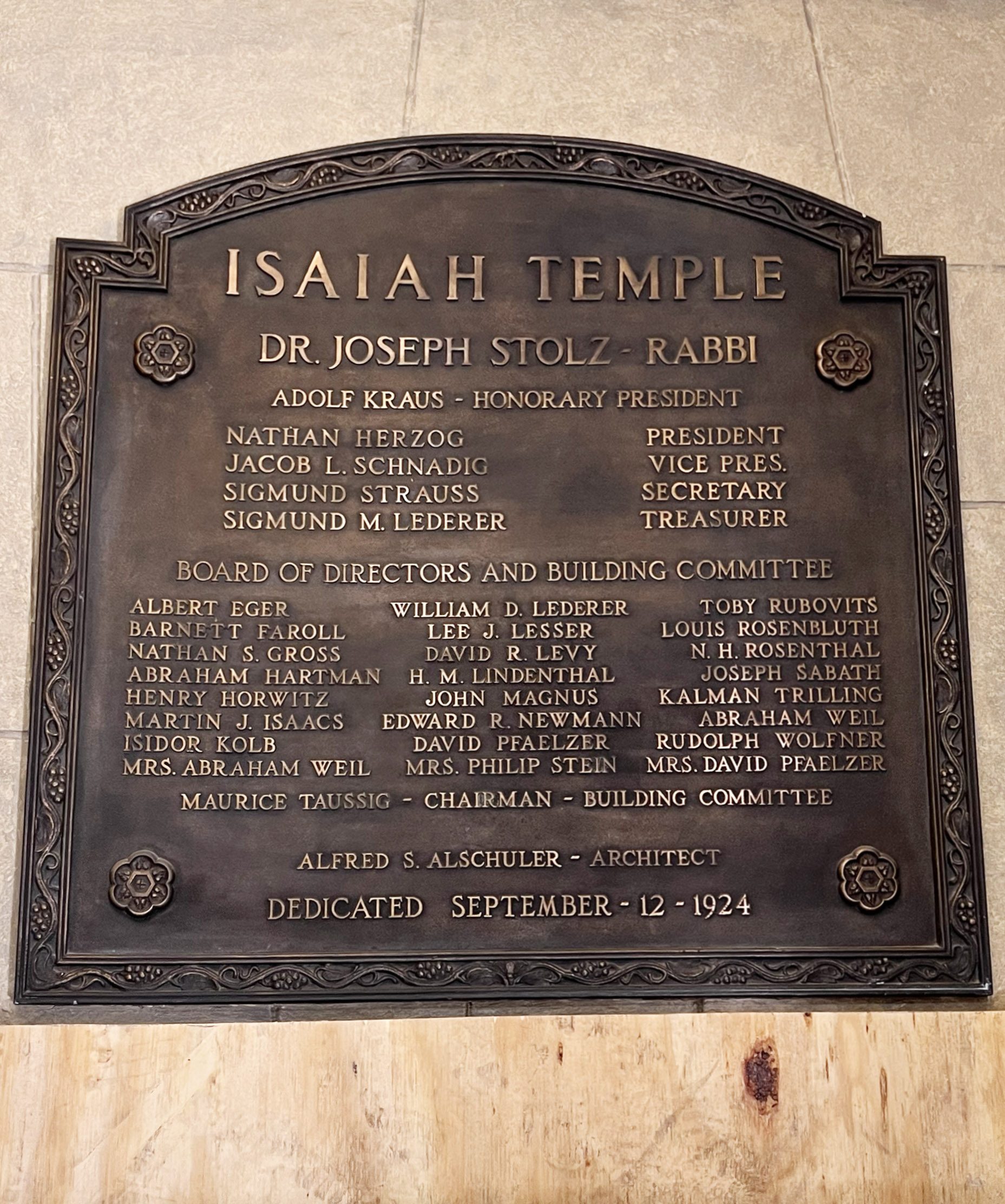

As the wider Jewish community grew, more offshoot congregations were created. Temple Israel (known as the “People’s Synagogue”), branched off from KAM in 1896. A decade later, B’nai Sholom and Temple Israel merged to become B’nai Sholom Temple Israel, originally meeting in Temple Israel’s building at Forty-Fourth and St. Lawrence Streets and later building a new purpose-built synagogue designed by Alfred Alschuler in 1914.

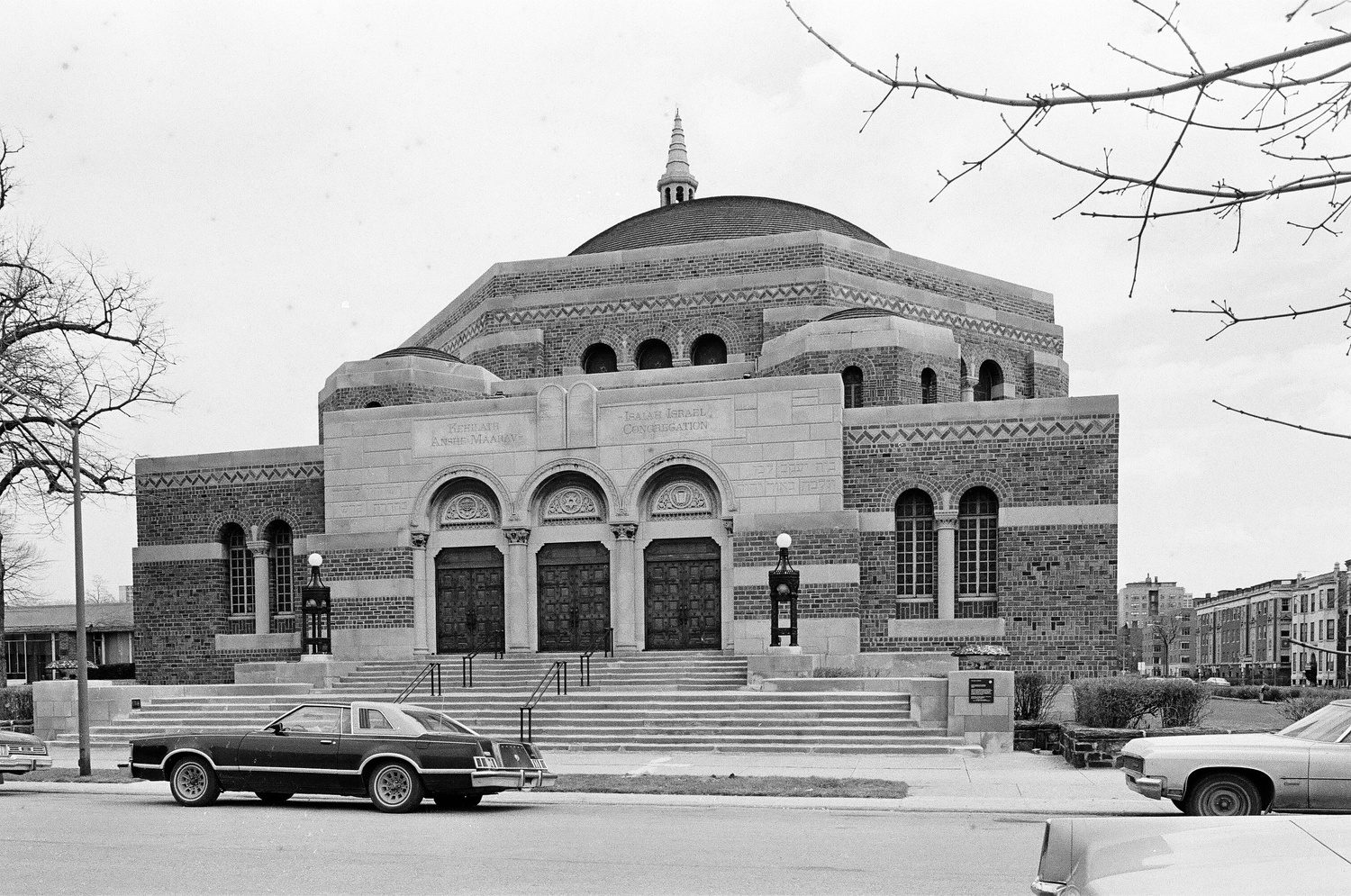

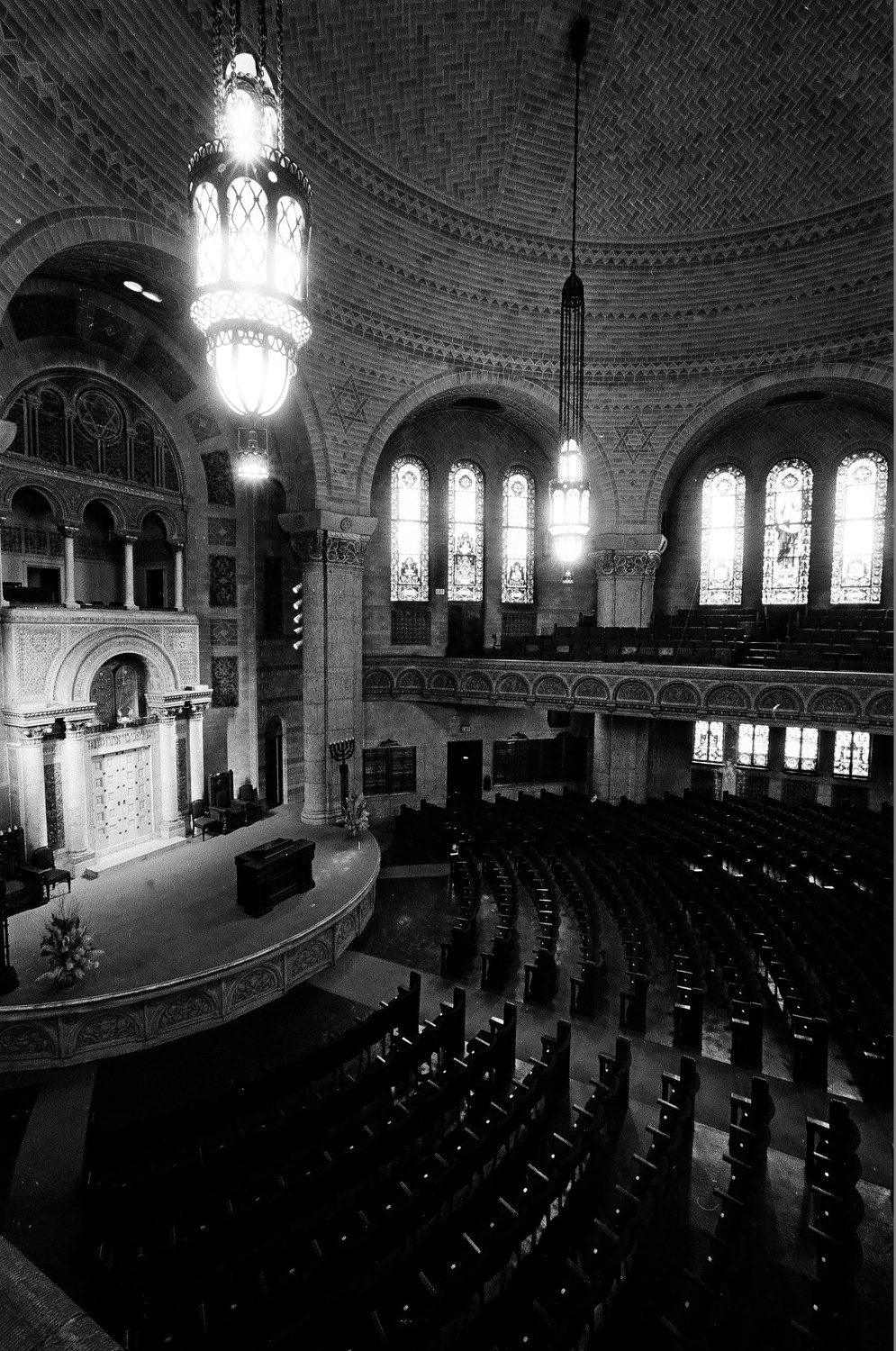

Exterior (top) and interior (below) of Temple KAM Isaiah Israel, 1979. ST-80004699-0024 and ST-80004699-0002, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

In 1924, further migration and mergers took place with Isaiah Temple, another outgrowth congregation that had formed in 1895. Together, the three congregations became known as Temple Isaiah Israel. The congregation built a stunning neo-byzantine synagogue in the Kenwood neighborhood, also designed by Alschuler.

Memorial plaques inside KAMII from its joining congregations, 2022. Photographs by Rebekah Coffman

In 1971, the congregational mergers came full circle as KAM joined Temple Isaiah Israel to also make Hyde Park Boulevard their home. Today, KAM Isaiah Israel (KAMII) is still an active, thriving congregation celebrating 175 years of presence in Chicago.

KAMII, exterior (top) and interior (below), 2022. Photographs by Rebekah Coffman

Additional Resources

- Read the Encyclopedia of Chicago entry on Chicago’s Jewish community

- See more of architect Alfred Alschuler’s work

- Read the Chicago History magazine article “Welcoming Jewish Americans” on the history of Chicago Hebrew Institute

Join the Discussion