DePaul University students Joseph Flynn, Jay Kietzman, Jessica Licklider, and Lily Zenger delve into the issues surrounding the Civil War monuments in the Chicago area. They were students of Peter T. Alter, the Museum’s historian and director of the Studs Terkel Center for Oral History, as part of DePaul University’s public history program. Former CHM intern and DePaul public history concentrator Sydney O’Hare edited their work.

While many familiar with Chicago’s history can recognize Grant Park’s iconic bronze statue of Union army general John A. Logan, few are aware of another Civil War monument that sits less than ten miles away in one of Chicago’s South Side cemeteries. Located near South Chicago Avenue and East Seventy-First Street in Oak Woods Cemetery, the Confederate Mound is a forty-five-foot-tall monument honoring the thousands of Confederate prisoners of war who died at Camp Douglas. Located in what is now the Greater Grand Crossing community, the camp was in operation from the war’s beginning in 1861 until its end in 1865. Both monuments were built in the 1890s, each receiving widespread attention from thousands of visitors when they were first unveiled.

A massive crowd joins city officials in the unveiling of the Logan Statue in Lake Park, now Grant Park, July 22, 1897. Photograph by George E. Mellen, ICHi-023906

The Confederate Mound, Oak Woods Cemetery, 2017. Photograph by Joe Flynn

In June of 1891, members of the Ex-Confederate Association of Chicago met to appeal to donors they considered sympathizers of the Confederate dead in order to construct a monument in their honor. The Ex-Confederate Association originally intended to debut the statue during the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, but the project was not finished in time. The 1895 dedication ceremony drew a significant crowd, including a visit from President Grover Cleveland and his whole cabinet.

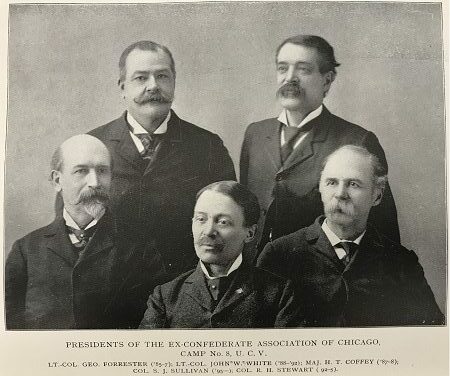

The presidents of the Ex-Confederate Association of Chicago from John C. Underwood, Report of proceedings incidental to the erection and dedication of the Confederate monument (Chicago: Johnston Print Co., 1896).

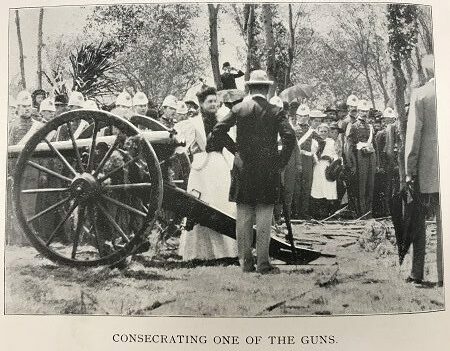

Soldiers gather around a man and woman preparing to “consecrate” the decorative cannons surrounding the memorial, 1895, from John C. Underwood, Report of proceedings.

Contemporary conversations about nationalism, historical understanding, and growing political tensions have made it especially important to reflect upon Confederate monuments and what they represent. Supporters of the monuments often claim that they represent southern heritage; however, a vast majority of the monuments were built from 1880 to 1910 in direct response to African American political gains in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. As modern scholars have suggested, therefore, rather than preserving southern pride, these monuments romanticize an era built upon white supremacy.

A crowd forms around the Confederate Mound for a Memorial Day celebration, June 1915. Photograph by the Chicago Daily News, DN-0064548

Because the Confederate Mound in Oak Woods Cemetery was originally constructed to be somber rather than celebratory, it presents a unique set of circumstances and requires a different reflection. Its location on burial grounds and connection to Camp Douglas set it apart from the prominently displayed monuments typically found in southern town squares, government buildings, and public spaces. Yet the question still remains—how does a nation come to terms with its past when debates over historical morality and regional pride persist, especially in public spaces?