Content warning: This blog post contains text and images about violence and sexual assault that may be traumatizing to some audiences. Reader discretion is advised.

Every July 13 marks a grim anniversary in Chicago’s history. On an otherwise normal Wednesday night, Jeffery Manor, in South Deering on the Far South Side witnessed what would later come to be called the “crime of the century.” In a townhome on 100th Street, mass murderer Richard Speck would torture, sexually assault, and ultimately murder eight nurses in one of the grimmest crimes in US history.

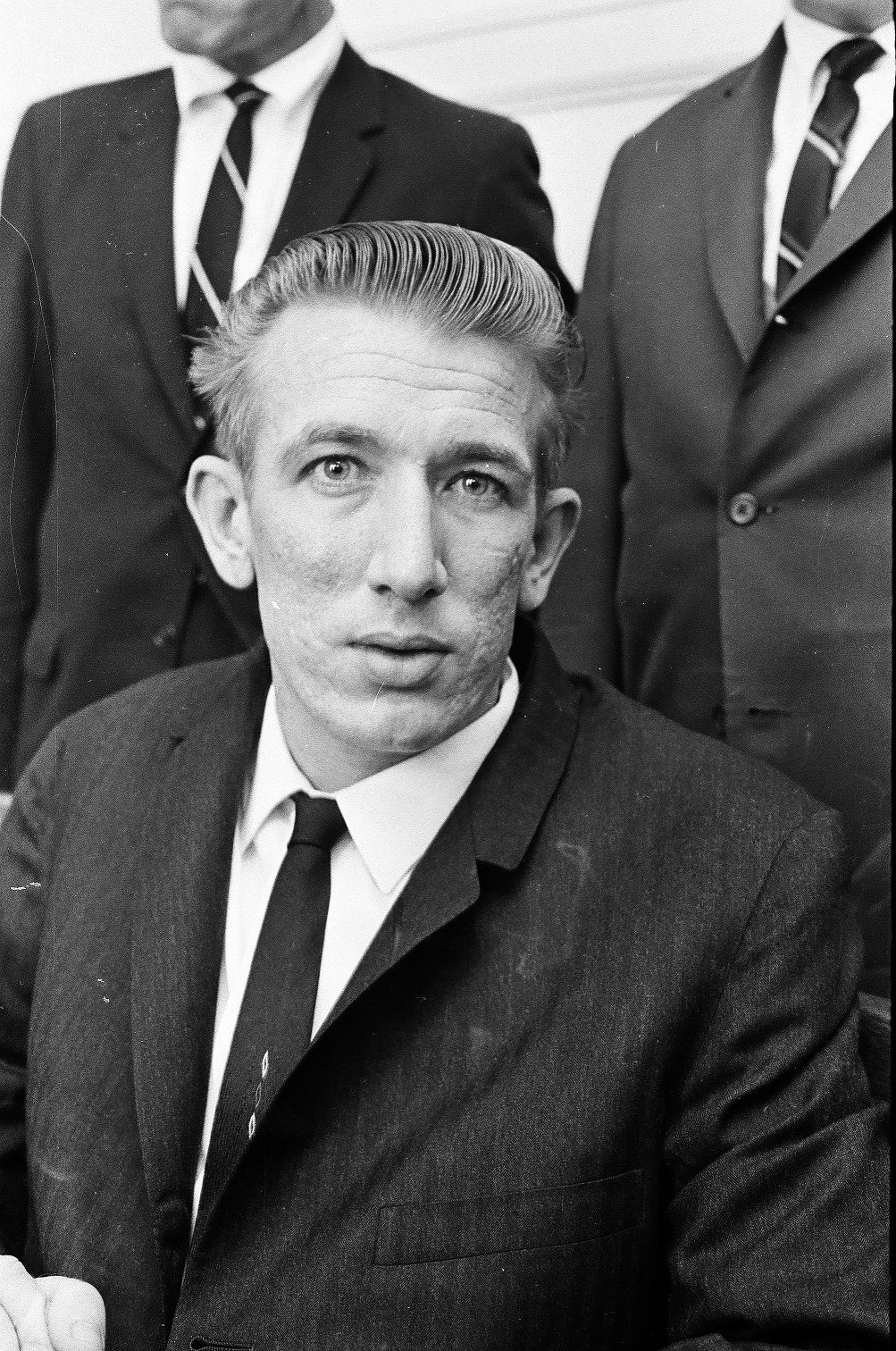

Murder suspect Richard Speck during his criminal court hearing at 2650 S. California Ave., Chicago, August 18, 1966. ST-19110229-0015, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Richard Benjamin Speck was born on December 6, 1941, in the village of Kirkwood, Illinois, about 200 miles west of Chicago. The seventh of eight children, Speck was born into a tumultuous low-income family, and he spent most of his youth growing up in the Dallas, Texas, suburbs where he regularly had run-ins with law enforcement due to his excessive drinking and penchant for public disturbances. Speck received his first major prison sentence in July 1963 at the age 21 when he was convicted of forging a signature on a stolen check and for the robbery of a grocery store. Originally due to serve three years, he was paroled after 16 months only to return to his cell a week later on charges of aggravated assault and a parole violation.

Speck would continue to add lines to his rap sheet in Texas before moving to Chicago to live with his sister in 1966. It was there that his brother-in-law found him work as an apprentice seaman. As was standard practice at the time, when he didn’t have work, Speck would check in at the National Maritime Union hiring hall, in the hopes of receiving an assignment to a vessel. It was a few days with no luck in securing work, on Wednesday, July 13, that Speck began his murderous rampage by sexually assaulting and robbing Ella Mae Hooper, a local woman he met at a bar.

The townhomes at 2319 E. 100th St., Chicago, July 22, 1966. ST-10000417-0010, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Later that night, around 11 p.m., the then 24-year-old Speck broke into a townhome that served as shared housing for foreign and local nursing students who worked at the local South Chicago Community Hospital. Here, over the course of a few hours he would be responsible for the murder of the eight women who were all inside the premises when Speck broke in. One woman, Corazon Amurao, escaped the death that met her housemates by hiding under the bed until the early morning. It took two days for authorities to apprehend Speck. Chicago Police received a lucky break and arrested Speck when a physician from the Cook County Hospital alerted them that a man they were treating following a failed suicide attempt was believed to be him. The physician had noticed a tattoo on the man’s forearm that read “born to raise hell,” and they recalled a newspaper description of the suspect that mentioned his ink.

Corazon Amurao, witness in the Richard Speck trial, entering the Peoria County Courthouse with her mother, 324 Main St., Peoria, Illinois. ST-19110250-0002, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

After being deemed competent enough to stand trial by a panel of medical professionals, Speck’s trial began in early April 1967 at the Peoria County Courthouse. The evidence against him was damning. In addition to the eyewitness testimony of Amurao, the lone survivor, fingerprints recovered at the scene matched Speck’s. The high-profile trial lasted less than two weeks, and after deliberating for less than an hour, on April 15, the jury found Speck guilty and recommended that he be served the death penalty. In June, a judge upheld the jury’s recommendation and sentenced Speck to death by electric chair. When the media referenced the trial, they often referred to Speck as a “mass murderer.” While today the term is part of everyday vernacular, referring to someone as a mass murderer in the 1960s was a new phenomenon.

Onlookers watch as police remove eight student nurses slain at 2319 E. 100th St., Chicago, July 14, 1966. ST-17500750-E1, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

On June 29, 1972, the Supreme Court ruled in the case Furman v. Georgia, thereby declaring the death penalty unconstitutional, which forced a resentencing for Speck. He received his new sentence in November of that year, ordered to serve from 400 to 1,200 years in prison through eight consecutive sentences. It would later be reduced to a sentence of 100 to 300 years. He would serve his sentence at the Stateville Correctional Center in Crest Hill, Illinois. While imprisoned, Speck unsuccessfully petitioned to be paroled no less than seven times. He died due to what is largely believed to have been a heart attack on December 5, 1991, in a hospital in the nearby town of Joliet, one day before what would have been his fiftieth birthday. He was cremated and his ashes were scattered in an undisclosed area.

The gruesomeness of Speck’s murders captured the fear and imagination of an entire generation, and has been retold in countless films, television episodes, and books. In the decades following the Speck murders, often referred to now as the Chicago Massacre, he only granted one interview to the media when he spoke to a Chicago Tribune columnist in 1978. In that interview, he admitted to being under the effects of alcohol and drugs, and further claimed to have had an accomplice, whom Speck murdered in fear that he would turn him in. No such proof of an accomplice has ever been found.

The names of Speck’s victims were Gloria Davy, Patricia Matusek, Nina Jo Schmale, Pamela Wilkening, Suzanne Farris, Mary Ann Jordan, Merlita Gargullo, and Valentina Pasion. All of them were in their early twenties and were robbed of their promising futures as caregivers and medical professionals. Pasion and Gargullo were both exchange students from the Phillipines. Their bodies were repatriated after a mass was held in their honor in Chicago.

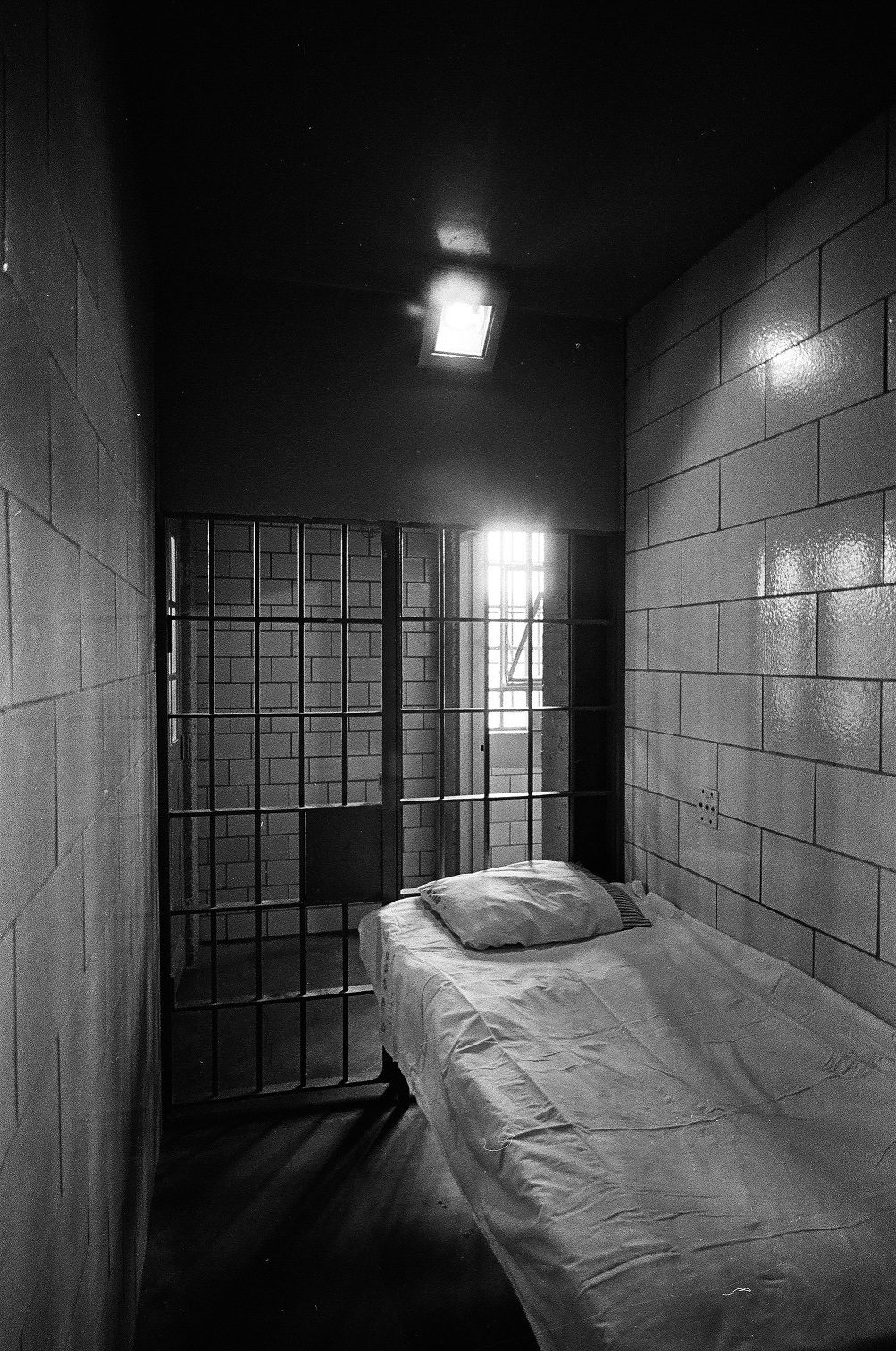

Cell at the Stateville Correctional Center that housed Richard Speck, Crest Hill, Illinois, May 1, 1967. ST-19110222-0044, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Additional Resource

- Listen to Studs Terkel’s 1967 interview with Dr. Marvin Ziporyn, Speck’s psychiatrist. (Note: Dr. Ziporyn did not testify for the defense or the prosecution, as both sides were troubled to learn before the trial that he was writing a book about Speck for financial gain.)