For Women’s History Month, head into storage with CHM collection technician Jessica McPheters for a closer look at two artifacts that document twentieth-century political strife and women’s suffrage in Chicago.

In the summer of 2016, the collections team began working on an inventory of the Decorative and Industrial Arts (DIA) collection at the Chicago History Museum. The process requires the team to pull artifacts from their storage areas so that we can record a number of details, such as the accession number (a numeric code that artifacts are assigned when cataloged into the collection), artifact location, measurements, photographs, and notes about the artifact’s physical description and condition. Collections inventory is necessary to update museum records and make them more accurate. It is also rewarding for the staff and interns to learn the history behind each artifact, as it enriches our daily work.

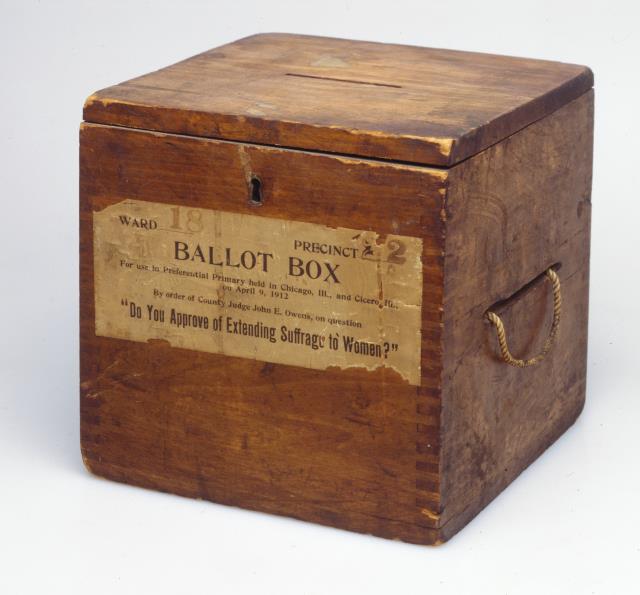

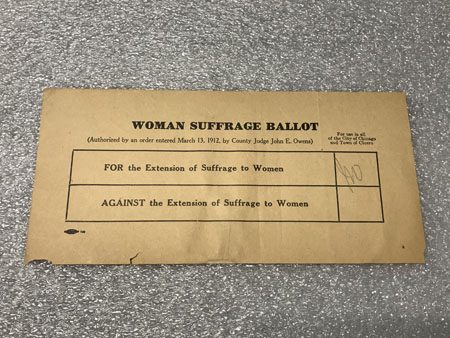

After 150 years of collecting, and with approximately 100,000 artifacts in the DIA collection, the discovery of treasures is often a daily occurrence. We found a few that tell the story of how women fought for the right to vote—a ballot box and ballot gauging Chicagoans’ support of women’s suffrage.

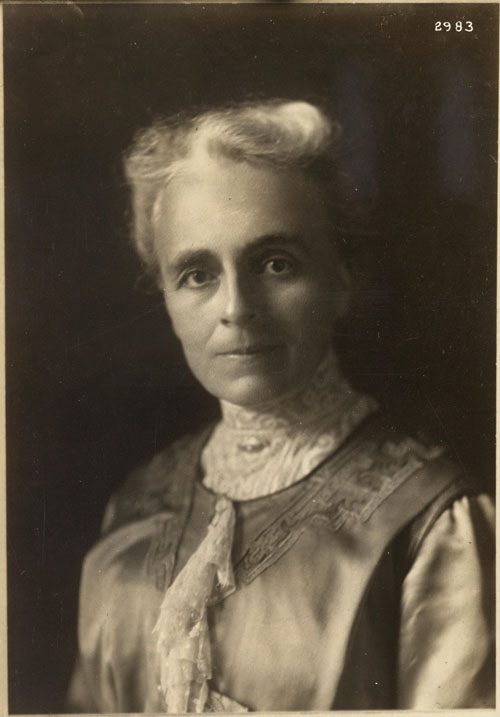

Judge Catherine Waugh McCulloch when she was justice of the peace of Evanston, Illinois, c. 1910. Photograph by the National Woman Suffrage Press Bureau. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, accessed March 6, 2018.

Catherine Waugh McCulloch was a respected lawyer and the first female justice of the peace in Illinois, serving in Evanston from 1907 to 1913. She was also a prominent suffragist who cofounded the Chicago Political Equality League in 1894, chaired the Legislative Committee of the Illinois Equal Suffrage Association (IESA) from 1890 to 1912, and led a whistle-stop train tour through the state in 1893 to rally support for a “statutory suffrage” bill she drafted that would allow Illinois women to vote in presidential elections.

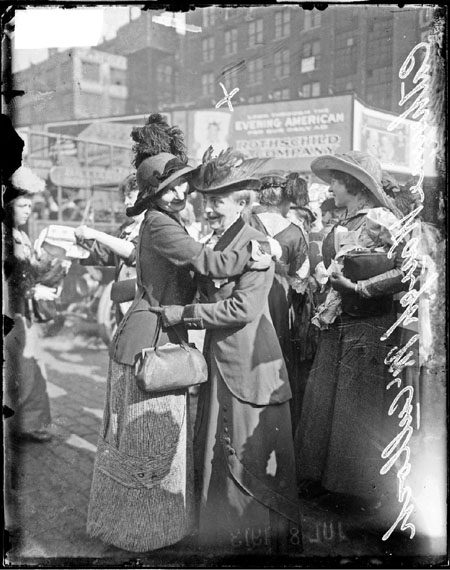

Catherine Waugh McCulloch (below x) embraces a fellow suffragette upon her return to Chicago from a trip to Springfield, Illinois, to campaign for the right of women to vote, June 14, 1913. Photograph by the Chicago Daily News, DN-0060623

By 1912, the suffrage movement in the Chicago area was gaining momentum and attracting the attention of many residents. McCulloch lobbied for a preferential ballot that broached the topic of women’s suffrage. Judge John E. Owens approved the ballot in March for the April 1912 primaries. This vote was similar to an opinion poll and, while it initiated conversation on the topic around the city, it was not highly favored in any of the city’s wards.

A wooden ballot box from Chicago’s 18th Ward for the 1912 preferential election. ICHi-032106

This paper ballot was found while inventorying the ballot box. Photograph by CHM staff

Overall, there were approximately 135,000 residents who voted against and around 71,000 residents who voted in favor of granting women the right to vote. Suffragists got to work organizing throughout the state, speaking to legislators about the movement. Illinois women enjoyed a victory on June 26, 1913, when Governor Edward Dunne signed into law the bill granting them the right to vote for presidential electors, mayor, aldermen, and most other local offices. There was still work to be done, however, because they could not vote for governor, state representatives, or members of Congress.

Mrs. George Taylor and Catherine Waugh McCulloch (front right) lead the Democratic women’s parade down LaSalle Street, Chicago, October 5, 1916. Photograph by the Chicago Daily News, DN-0067219

On June 10, 1919, Illinois became one of the first states to ratify the 19th Amendment. There were still limitations and restrictions placed against women voters until 1920 when the 19th Amendment was adopted by Congress and full suffrage was granted to women around the country.

Additional Resources

- Visit our exhibition Facing Freedom in America to learn more about the fight for suffrage

- Explore the Museum’s collection