This post is from Marissa Croft, CHM’s research and insights analyst and author of our Fashion and Costume Research Guide. As a PhD candidate at Northwestern University, she also researches the clothing of the French Revolution and women’s clothing reform movements of the 19th century.

As December dawns, many Chicagoans may find themselves fondly reminiscing about making a special seasonal trip to Marshall Field’s department store to experience its yearly transformation into a holiday wonderland. The decorated State Street windows and the record-breaking Christmas tree of the Walnut Room were not only intended to spark wonder and delight from visitors, but long-term brand loyalty. Field’s commitment to elevating the Christmastime retail experience through art was in large part fostered by an artist named Clara Powers Wilson, who served in many roles at the store, including working as the art director of the company’s most successful publication, Fashions of the Hour.

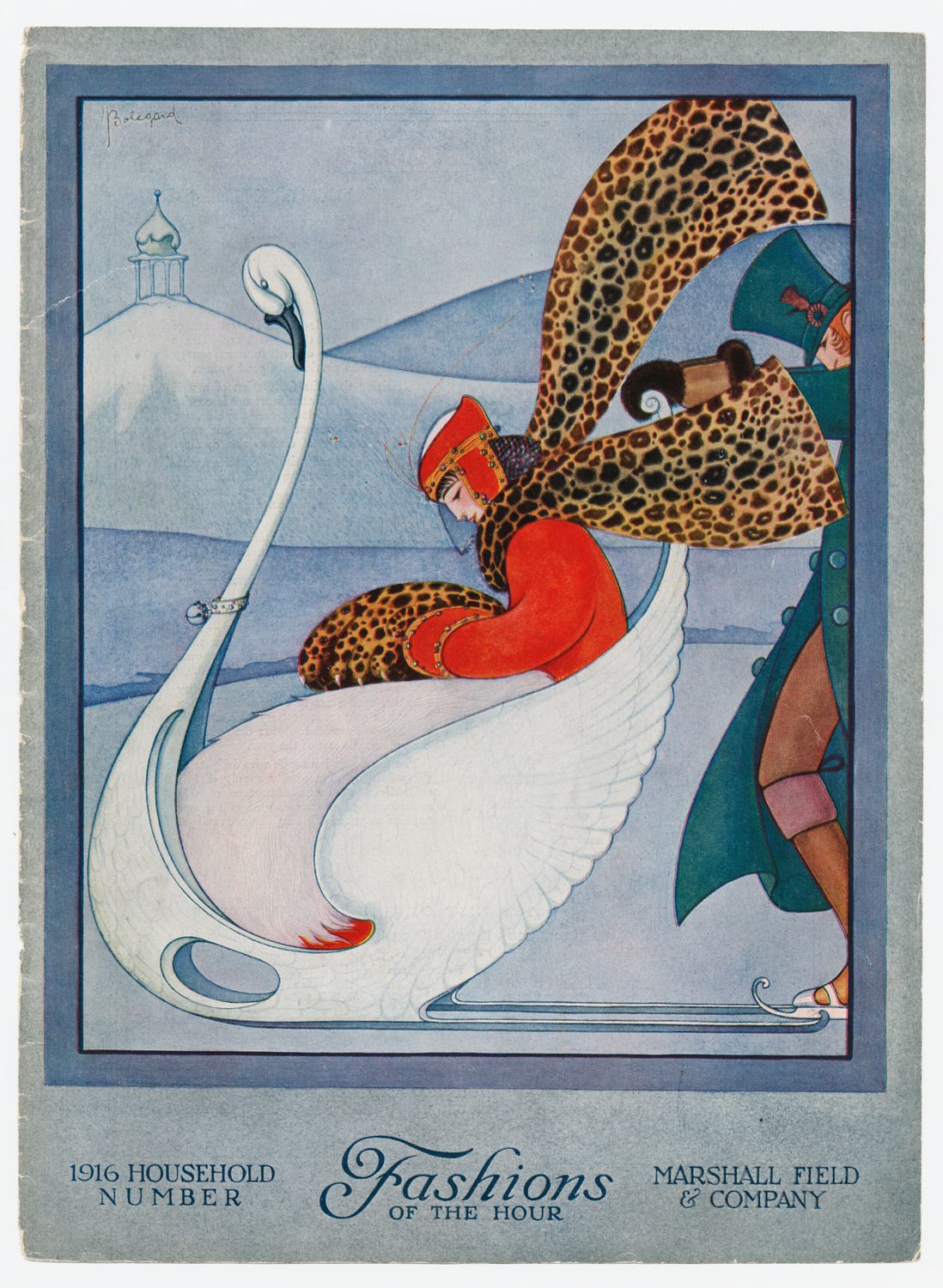

Cover of Marshall Field’s Fashions of the Hour, 1916. CHM, ICHi-073734

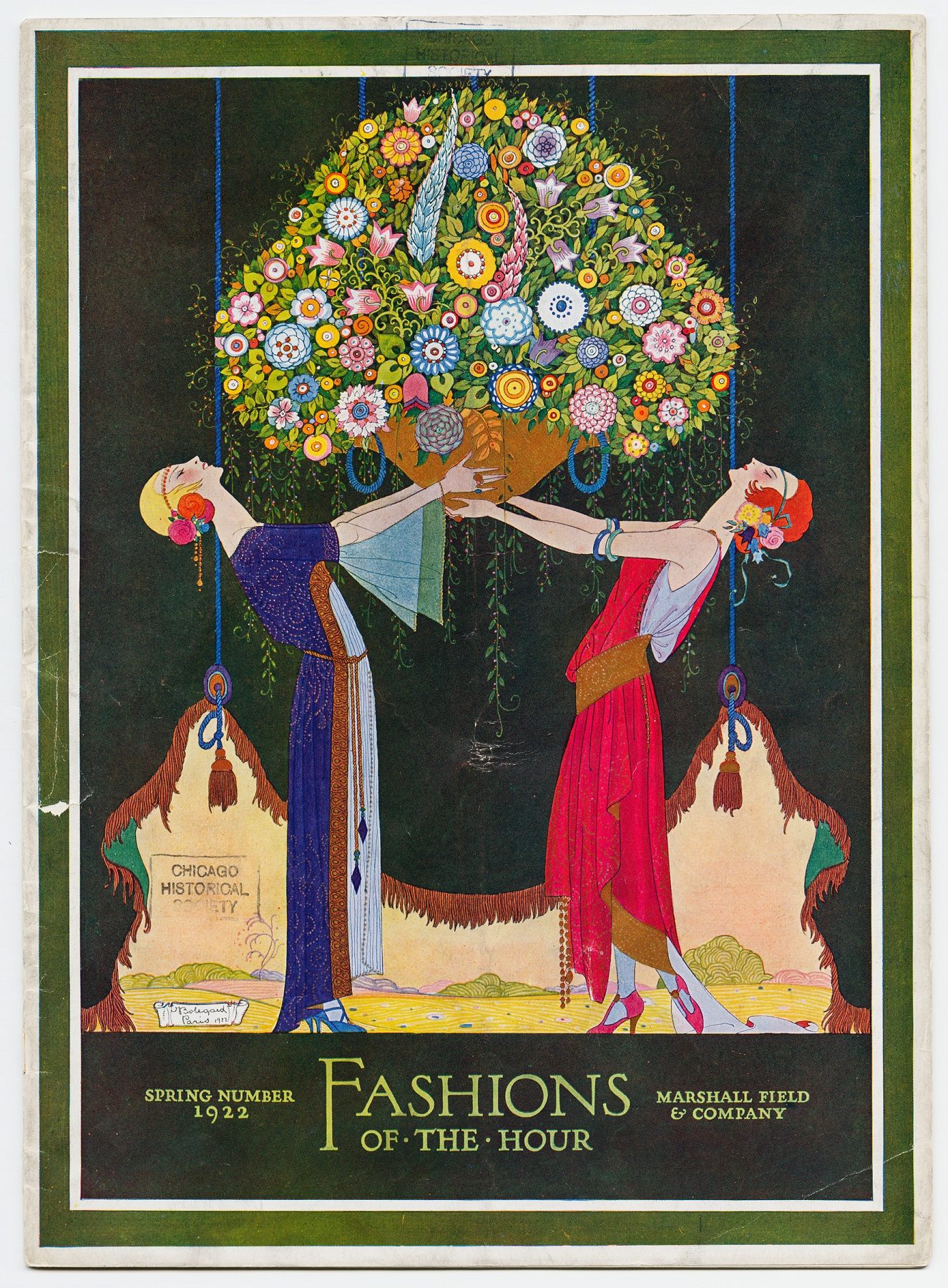

The first edition of Fashions of the Hour came out in October 1914 and the magazine ran until 1978. Initially, a copywriter named René Mansfield was the sole editor of the publication, but Clara Wilson soon joined her as art director, and it was during Wilson’s tenure that the publication reached its artistic peak. Fashions of the Hour set itself apart from other commercial catalogs in several ways. First, it was published six times a year and featured lavishly colored covers and interior illustrations by some of the most famous French and American Art Deco artists of the era. Second, they sold no space to advertisers, which meant every page of the twenty-to-forty-page magazine could be completely devoted to illustrations of store products, articles about art and society in Chicago, short literary pieces, travelogues, and photographs of famous people dressed in the latest fashions. Finally, the magazine was free, and its peak circulation in the mid-1920s reached over 100,000 people. Without the benefit of paid ads, it cost Marshall Field’s roughly $250,000 annually to publish.

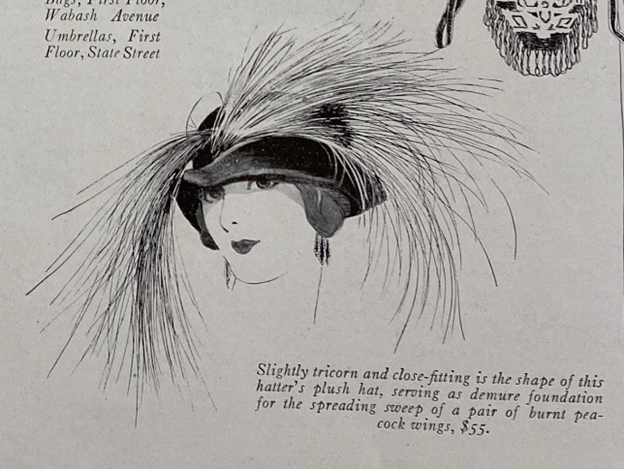

An example of the product illustrations that were featured in the magazine. From the Autumn 1922 issue: “Slightly tricorn and close-fitting is the shape of this hatter’s plush hat, serving as a demure foundation for the spreading sweep of a pair of burnt peacock wings, $55.” (In 1922, $55 had the same purchasing power as $972 in 2022.) Photograph by CHM Staff.

Wilson’s leadership of Fashions of the Hour was just one of many of her contributions to retail history, however. Born in 1873 in Michigan as Clara Powers, she studied under James McNeil Whistler at the Whistler School in Paris and the Art Institute of Chicago. In 1898, she married Louis William Wilson, a fellow artist who worked as an instructor of color theory at the Art Institute. Wilson started her career as a freelance artist around the same time, specializing in illustrating children’s books and designing illustrated journals for recording recipes, addresses, and memories.

An illustration by Wilson for Cheery and the Chum, a children’s book published in 1908. Library of Congress Public Domain Archive.

Wilson’s career at Field’s began in 1914, when she was hired to serve as the indoor counterpart to Arthur Fraser, the artist responsible for creating the year-round State Street window displays. Her job was to select draperies, decorations, and lighting effects for everywhere in the store’s interior except the main aisle and light wells (also Fraser’s territory). When she insisted on covering the up the expensive, solid mahogany paneling in the Women’s Salon to achieve a more flattering lighting scheme for the patrons trying on clothing, general manager David Yates objected, and she was sent to serve a stint in the advertising department.

Cover of Marshall Field’s Fashions of the Hour, Spring 1922. CHM, ICHi-051295

Charged with the art direction of Fashions of the Hour and with increasing traffic to neglected areas of the store, Wilson turned her eye first to the housewares department. She proposed holding cooking classes in the store, rearranging the stock, and even pushing utensil manufacturers to paint implement handles different colors so shoppers could match them to their kitchens. These efforts were so successful that she and her two assistants were soon given free reign over the presentation of merchandise throughout the store. In 1916 Wilson was appointed the first official Christmas tree designer, and she quickly set the precedent for the level of lavish seasonal decorations that would persist at Field’s until it was purchased by Macy’s in 2006.

Christmas tree at the Marshall Field’s Walnut Room, 1966. ST-40002977-0001, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

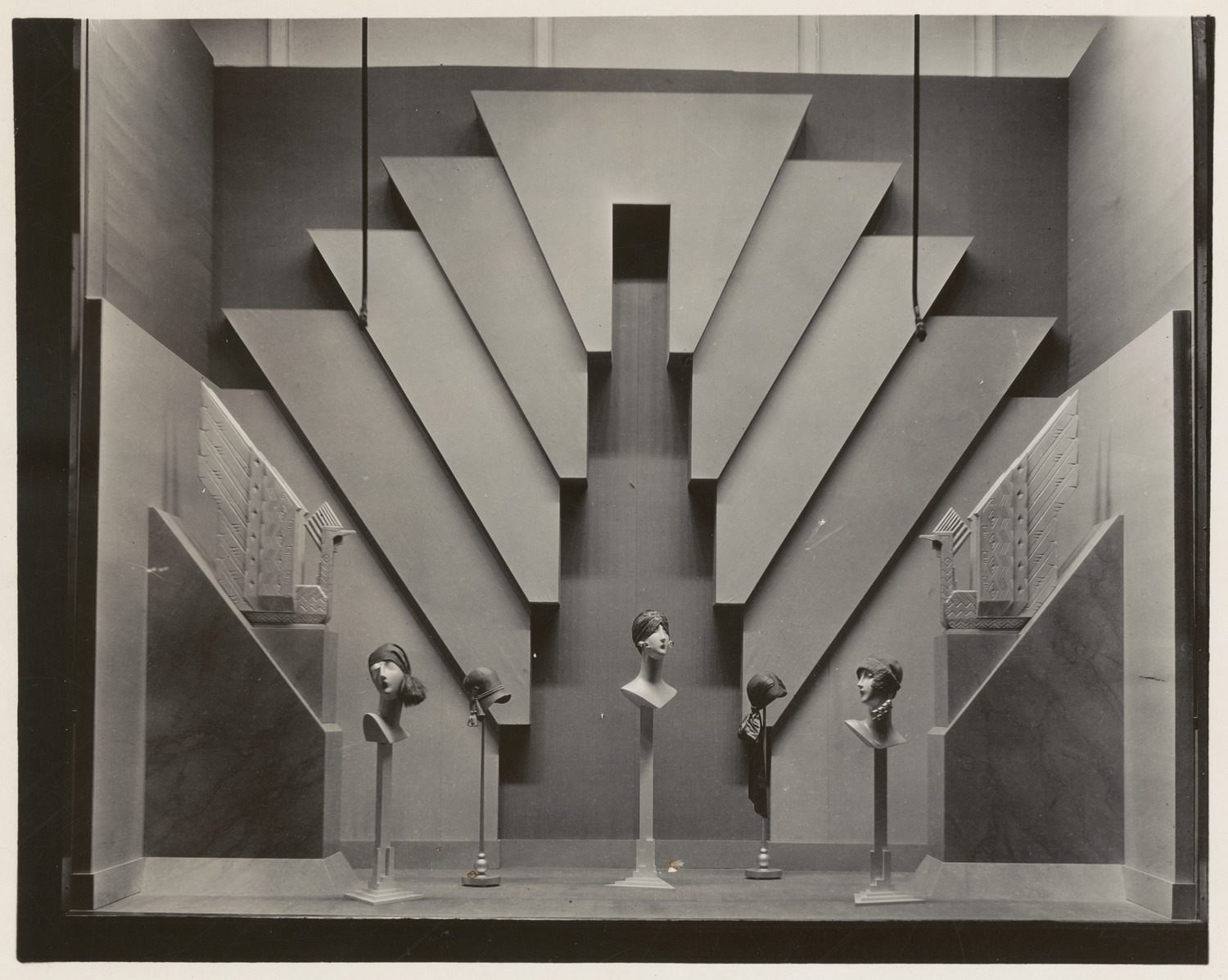

Wilson’s career did not slow, even after the unexpected death of her husband in 1919. In late 1922 she moved to New York with her four children to serve as the managing editor of Harper’s Bazaar. To the surprise of many, she returned to her position at Field’s a few years later, and immediately began advocating for even more drastic changes to the way merchandise was displayed. Continuously drawing on her artistic background and deep understanding of color theory, Wilson noted in a 1946 interview that during the late 1920s she was the one who “had the idea to bunch associated articles” and that she also “introduced match colors so a customer could have an ensemble of color.” Perhaps her most daring move was taking one of Fraser’s window display mannequins and putting it inside the store underneath a spotlight that many feared would scorch the dress.

A Marshall Field’s display for hats circa 1928 featuring Art Deco-inspired sculptures and backdrop. CHM, ICHi-092922, Marshall Field and Company archives. Gift of Federated Department Stores.

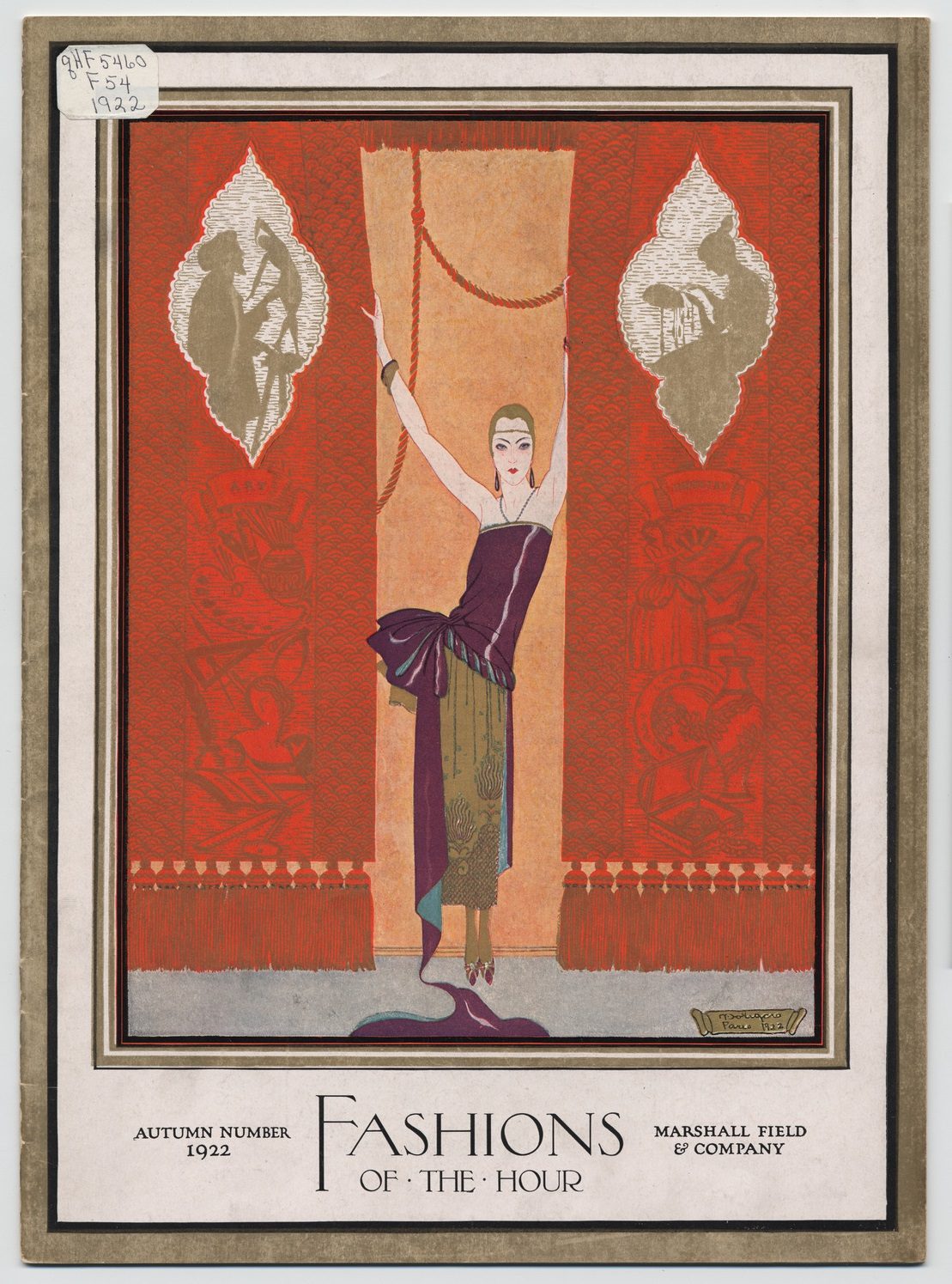

The Autumn 1922 edition of Fashions of the Hour was one of the final issues of the magazine that Wilson oversaw before departing for New York and it was dedicated to highlighting the intersections of art and industry. In one article, Robert B. Harshe, the director of the Art Institute of Chicago, noted that “a product is not finished today unless the element of beauty as well as the element of utility is present.” Wilson’s work at Field’s was the embodiment of this philosophy. From catalogs to kitchen implements, she expertly blended form and function to elevate these common commercial goods into artistic objects.

Marshall Field’s Fashions of the Hour, Autumn 1922. Note that the themes for the issue, “art” and “industry,” are subtly illustrated on the two curtains in the image. CHM, ICHi-040590

Additional Resources

- View more images of Fashions of the Hour

- See the Federated Department Stores’ records of Marshall Field & Company, c. 1852–2004, at the Abakanowicz Research Center, which is free to visit

- Order Fashions of the Hour prints from the CHM PhotoStore

Sources

- Art Deco Chicago: Designing Modern America (Chicago Art Deco Society, 2018)

- Emily Kimbrough, Through Charley’s Door (Harper & Row, 1952)

- Encyclopedia of Chicago, “Field (Marshall) & Co.” (Chicago History Museum, 2005)

- William Leach, Land of Desire: Merchants, Power, and the Rise of a New American Culture (Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2011)

- Lloyd Wendt, Give the Lady What She Wants!: The Story of Marshall Field & Company (And Books, 1979)

See what people are saying!