As part of her work on our upcoming exhibition Aquí en Chicago, CHM curator of civic engagement and social justice Elena Gonzales has been examining how we can find Latin American heritage in unexpected places that connect us to unexpected allies and unknown cousins.

Latin American heritage is broad, and our tidy ideas about what this “region” is are often incomplete. Here is a brief look at a few examples that help us understand the concept of a global Latin America, where colonizer, language, and geography do not neatly determine the boundaries of the region.

Haiti

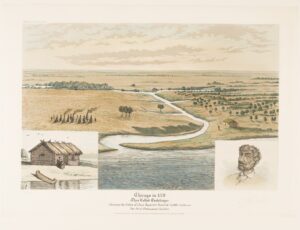

Chicago’s first non-Native permanent settler, Jean Baptiste Pointe DuSable (d. 1818), was Haitian. Our Latine history starts before Chicago was even a city.

Engraving titled “Chicago in 1779,” depicting the cabin of Jean Baptiste Pointe DuSable and his portrait, c. 1926–32. Published by A. Ackermann & Sons Inc. CHM, ICHi-005623; Raoul Varin, artist

The first stop for Christopher Columbus in the Americas was La Navidad in what is now Haiti. There, Columbus encountered Taíno people, part of the Arawak group of Indigenous people, who Europeans also encountered in what would become Puerto Rico. Today, the Taíno word “Boricua” refers to a Puerto Rican identity with a backbone of Indigeneity.

World’s Columbian Exposition souvenir coin purse with a painted scene depicting the landing of Christopher Columbus, Chicago, c. 1893. CHM, ICHi-036259

This heritage connects Haiti and the Dominican Republic (DR), which share the island of Hispaniola. The two nations also have a legacy of division based on race and religion that is still playing out today. They developed differently through different patterns of colonization—predominantly Spanish in DR and Spanish (1492–1625) followed by French and then the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804) in Haiti.

Haiti’s revolution in 1804 ended the largest revolt by enslaved people in history, and Haiti became the first free Black republic in the Western Hemisphere. Following the Haitian Revolution, colonial powers such as Spain, France, and the United States sought to distance Haiti from Latin America even further, culturally and politically. They feared that Haiti’s example would inspire additional Latin American nations to seek independence. Thomas Jefferson cut off aid to François-Dominique Toussaint L’Ouverture, the leader of the Haitian Revolution. The United States did not recognize Haiti as an independent nation until 1862. The first president of Haiti, Alexandre Sabès Pétion, aided Simón Bolívar in liberating Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, Panama, and Bolivia.

There are approximately 40,000 Haitians in the Chicago area, and the Haitian American Museum of Chicago (HAMOC) is an advisor of CHM, as is the Dominican American Midwest Association (DAMA). Haitian migrants continue to migrate to Chicago, as it is a sanctuary city. HAMOC provides legal resources regarding immigration to Haitian and non-Haitian new arrivals and migrants throughout Illinois.

Brazil

Despite Brazil’s colonization by the Portuguese rather than the Spanish, the US Census categorizes Brasileiros as “Hispanic or Latino.” This is another illustration of the entangled identities within Latine as a category.

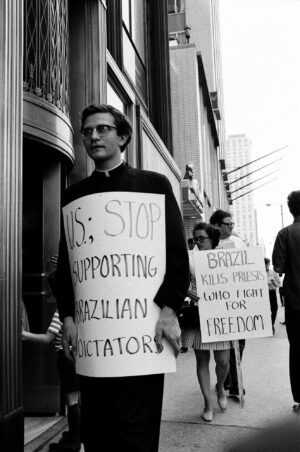

In the 1980s, Brazilians came to Chicago during the dictatorship of João Figueiredo (1964–85), whose regime the United States helped establish. Brazilians in Chicago tend to be middle class and tend to stay in Chicago to work or attend school before returning to Brazil or settling in suburbs.

Members of the Brazilian Consulate protest the murder of Father Antonio Henrique and other Brazilian priests, 903 N. Michigan Ave., Chicago, June 26,1969. ST-60002649-0011, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Brazilian identity is complicated. Many light-skinned Brazilians in Chicago prefer the European identity of “Portuguese” on the census. Afro-Brazilians select “Black not Hispanic,” putting race first. Geopolitically, they also identify as Latin American. There are approximately 55,000 Brazilians in the Chicago area, and the Brazilian Cultural Center is an advisor of CHM.

Philippines

The Philippines is a Southeast Asian nation comprising 7,641 islands with a diverse history of intra-Asian migration and European colonization. During nearly four centuries of colonization in the Philippines, the Spanish profoundly influenced everything from the name of the islands to the form of governance, economy, cuisine, agriculture, religion, social structure, and language. The Hispanic presence in the Philippines also involved trade between Mexico and the Philippines during the 1600s, which resulted in Filipinos living in Mexico and vice versa.

Milk glass dish by Westmoreland Specialty Co. in the shape of an eagle sitting on a nest of eggs, 1898. The ribbon on the front says “The American Hen,” and the eggs are labeled “Purto Rica” (Puerto Rico), Cuba, and Philippines. The design is influenced by the Spanish American War. CHM, ICHi-179109

From the mid-18th century on, Filipinos rebelled against the Spanish, who ruled the Philippines from Mexico until Mexican independence in 1821. By the 1860s, only 5–10% of the population spoke Spanish fluently. The government sought to increase that rate, but Filipinos sought independence. Filipinos nearly had independence in their grasp when the United States stepped in to “assist” in their revolution. Instead, they took over colonial rule from Spain. The United States immediately went to war against the Filipino Revolution (1899–1902/1912) even while working on terms for the Philippines as a new colony.

Portrait of a Filipino string sextet at the WMAQ radio station, Chicago, December 1924. DN-0078368, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

During World War II, the United States and Japan grappled for control of the islands. The Philippines ended up independent but still burdened by their relationship to the United States. According to the Pew Research Center, approximately 145,000 Filipinos live in the Chicago area. The Filipino American Historical Society of Chicago is an advisor on this project.

Belize

Like its neighbors, Mexico and Guatemala, Belize was part of the Maya empire for nearly three millennia, from possibly as early as 1500 BCE to roughly 1200 CE. In the 16th and 17th centuries, the Spanish and British fought over which nation would control Belize as a colony, and Britain won. Belize gained independence from Britain in 1981 but remained part of the Commonwealth. Thus, even though it is geographically part of Latin America, it has some important cultural differences.

In addition, Belize has multiple types of Indigenous cultural heritage, both Maya and Garinagu. The Garinagu people (who speak Garifuna) are descendants of pre-Columbian African traders and Indigenous people of South America. They migrated to the Caribbean island of St. Vincent between 160 and 1220 CE. There, the Spanish, Dutch, French, and British fought for control of the Garinagu land for 300 years until Britain ultimately won. After the Garinagu failed in their rebellion against the British in the 1790s, roughly 5,000 Garinagu were exiled from St. Vincent to Belize, helping to create the mixed population in that country today. Chicago is home to a Garinagu and partly Garifuna speaking population.

Exterior of Garifuna Flava restaurant, 2518 W. 63rd St., which is know for their Caribbean, Latin, and indigenous Garifuna cuisine, July 2024. Image from Google Maps.

There is much more to learn about places that touch on these shared histories. For those interested in more research, the histories of Guyana, Grenada, Guam, Equatorial Guinea, and the Marianas are excellent next steps.

Further Reading

Clémence, Jouët-Pastré, Leticia J. Braga, eds. Becoming Brazuca: Brazilian Immigration to the United States. David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, Harvard: 2008.

Kahn, Jeffrey S. Islands of Sovereignty: Haitian Migration and the Borders of Empire. Chicago Series in Law and Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018.

Ocampo, Anthony Christian. The Latinos of Asia: How Filipino Americans Break the Rules of Race. 1st ed. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2016.

Page, Joseph A. The Brazilians. Boston: Da Capo Press, 1996.

The Garifuna Journey.Mov, 2021.