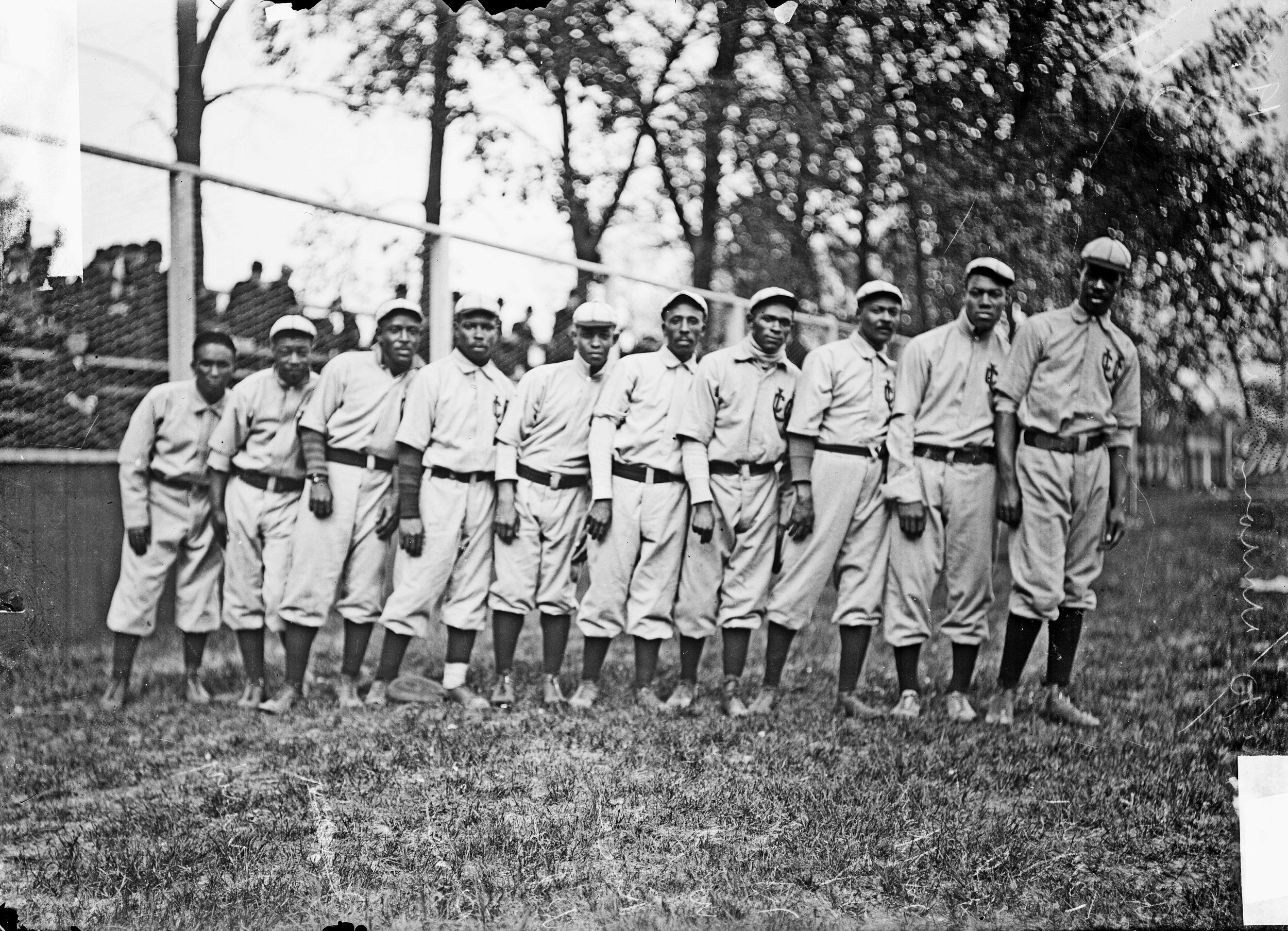

July 2024 marks 45 years since the infamous “Disco Demolition Night” promotional event at a July 12, 1979, Chicago White Sox twilight doubleheader against the Detroit Tigers that erupted into chaos. To encourage attendance, the White Sox hosted WLUP 97.9 rock DJ Steve Dahl, who was known for mocking disco and had been fired from a previous radio job when the station switched from rock to disco. They asked fans to bring a disco record to the ballpark in exchange for 98-cent admission, and those LPs were to be gathered and then blown up in a controlled explosion between games.

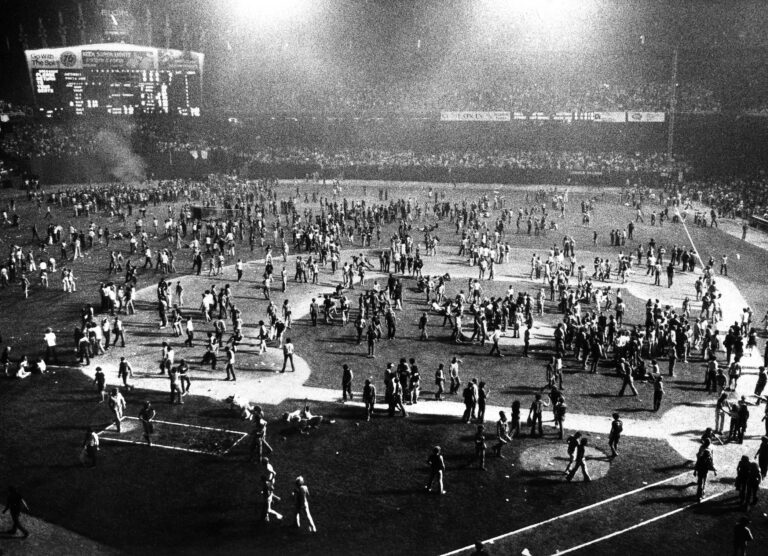

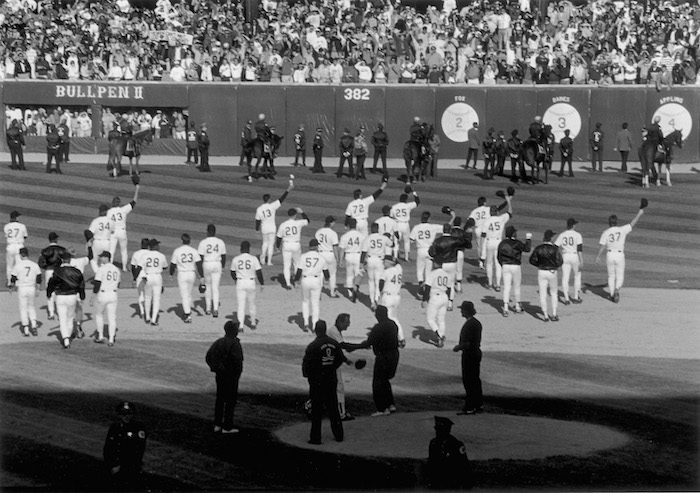

Some of the overcapacity crowd storms the field at Comiskey Park on Disco Demolition Night, Chicago, July 12, 1979. ST-17500752-E1, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM; photograph by Chuck (Charles) Kirman

That season, the White Sox had been averaging 15,000 attendees per game at Comiskey Park, which at the time had a seating capacity of 44,492. With the promotion, along with discounted admission for the simultaneous “Teen Night” promotion, the Sox were hoping for 20,000 attendees. A record crowd showed up—officially 47,795, but an estimated more than 50,000 got into ballpark and approximately 15,000 to 20,000 people lingered outside. During the first game, the crowd of mostly young people was disruptive, throwing uncollected LPs, empty bottles, lighters, and firecrackers onto the field, stopping the game several times.

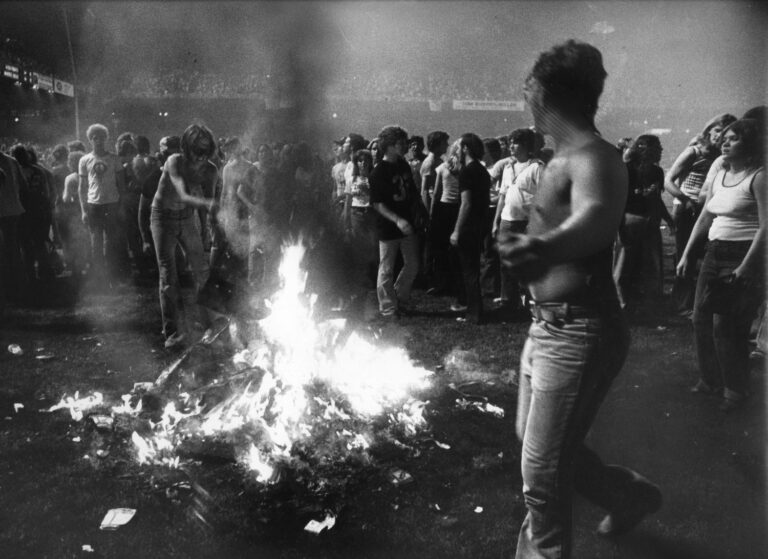

Crowd sets rejected records on fire at Disco Demolition night in Comiskey Park, Chicago, July 12, 1979. ST-17500981-E1, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM; photograph by Jack Lenahan

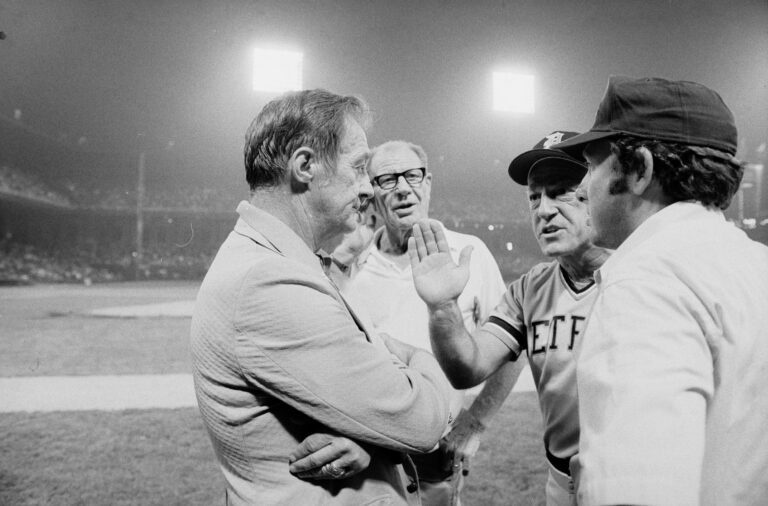

Though a crate of records was blown up by Dahl in center field between games as planned, as the Sox started to warm up for game 2, attendees started to rush onto the field. With security focused on keeping gate-jumpers from entering the ballpark from outside, the crowd could not be held back. An estimated 7,000 people were on the field for 40 minutes before security and police in tactical gear were able to remove them. In that time, a bonfire was set in center field, a batting cage was destroyed, and bases were stolen. Ultimately 39 people were arrested, and the Sox had to forfeit game 2.

Bill Veeck, president of the Chicago White Sox, tries to reason with umpires and Sparky Anderson, Detroit Tigers manager, after a crowd rushed the field during Disco Demolition Night, Chicago, July 12, 1979. ST-18000030-0009, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM; photograph by Kevin Horan

Though Dahl claimed afterward that there was no intentional bigotry behind his anti-disco stance, Disco was originally connected to Black, Latine, and queer spaces before it saturated the mainstream market and met with backlash, often from white, heterosexual, male rock-music listeners. Ushers at Comiskey Park noted that attendees also brought funk and R&B records—other genres associated with Black artists—to be destroyed. Nile Rodgers, cofounder of the disco band Chic, said that in looking at the footage the next day, “it felt to us like a Nazi book burning.”

A man sells “Disco Sucks” t-shirts outside of Comiskey Park on Disco Demolition Night, Chicago, July 12, 1979. ST-18000030-0014, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM; photograph by Kevin Horan

The “disco sucks” movement was largely a marketing gimmick, targeted to the young white male demographic, as rock radio stations found that creating “disco sucks” clubs increased their listenership. Disco, which was already declining in popularity by 1979, went on to influence house music, EDM, Europop, new wave, dance-punk, and hip-hop and has seen revivals in the 21st century. Rather than destroying the genre, Disco Demolition Night is remembered as an extreme promotional event and one of only five MLB games to end in a forfeit since the post-1960 expansion era.

Comments