Claude M. Lightfoot (1910–1991) was an African American author, Chicago resident, political candidate, and member of the Communist Party USA’s national committee. In 1986, he donated a collection of his papers to the Chicago History Museum.

Portrait of Claude M. Lightfoot from Harold Marcuse, The Case of Claude Lightfoot, 1955 brochure. Public domain.

Born in Lake Village, Arkansas, in 1910, Claude Mark Lightfoot was raised by his grandmother until 1918 when the Lightfoot family moved to Chicago as part of the Great Migration. The Chicago Race Riots of 1919 stirred Lightfoot’s interest in politics and racial equality that would drive his life’s work.

In the wake of World War I, he joined Marcus Garvey’s Pan-Africanist movement, but he soon became convinced the ideology was unworkable. After a brief time at Virginia Union University—where he was expelled after the school discovered he did not have a high school diploma—he returned to Chicago in 1929.

Lightfoot joined the Democratic Party and helped found the Young Men’s Black Democratic Club in Chicago (1930). At this point in his political development, he was convinced that the answer to the plight of African Americans would be found in business enterprise. However, the Great Depression and the lack of progress and action regarding Black Americans’ financial and political standing convinced him otherwise.

In 1931, Lightfoot joined the Communist Party USA (CPUSA). In summer 1932, he attended a workers’ school organized by the Party, and later that year he ran for Illinois State Legislature on the Communist Party ticket and received 33,000 votes. By 1935, Lightfoot was a delegate to the Seventh World Congress of the Communist International in the Soviet Union.

After the Nazis declared war on the Soviets during World War II, Lightfoot enlisted in the US Army in 1941. The prejudiced treatment of both Communists and Black soldiers by the Army deepened Lightfoot’s belief in socialist government. He resumed his CPUSA activities upon his return home three years later. In 1946, Lightfoot prepared to run for the Illinois State Senate on the CPUSA ticket; however, his petition was successfully challenged by the Democratic Party—the Cold War had begun.

Undated photograph of Claude Lightfoot (right) with Jack Kling at an unknown location. CHM, ICHi-039210

On June 26, 1954, Lightfoot, then serving as the executive secretary of the Communist Party of Illinois, was arrested and charged with Communist Party membership and knowledge of the Party’s objectives “to teach and advocate the overthrow of the government of the United States by force and violence as speedily as circumstances would permit” as specified in the Smith Act of 1940. It was the first indictment under this clause, so Lightfoot’s case was a test case for both the defense and prosecution. Lightfoot believed the federal government targeted him to send a message to Black Americans to stay away from the Communists (and civil rights activities in general).

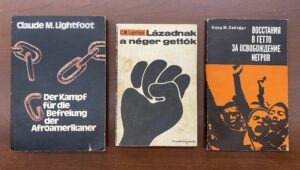

German, Hungarian, and Russian translations of Lightfoot’s Ghetto Rebellion to Black Liberation. Claude M. Lightfoot papers, Series 2, Box 2.

Lightfoot’s case was appealed all the way to the US Supreme Court, where Lightfoot was acquitted in 1964. That year, the Supreme Court also struck down the provision of the McCarran Act that withheld passports to CPUSA members. From 1964 until his death in 1991, Lightfoot worked for the CPUSA as a party officer and sought the advancement of Marxist-Leninist ideals. He wrote numerous books and articles about racism and communism and gave lectures around the world. In 1973, he received an honorary doctorate from the University of Rostock in Germany for his book, Racism and Human Survival: Lessons of Nazi Germany for Today’s World.

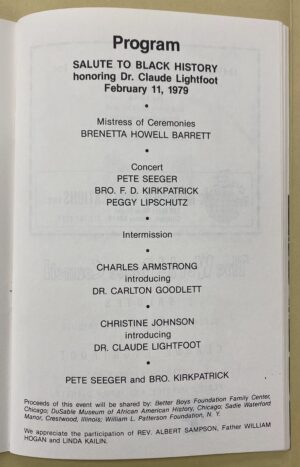

“Salute to Black history honoring Dr. Claude [M.] Lightfoot,” Feb. 11, 1979 program. Claude M. Lightfoot papers, Series 1, Box 1, Folder 23.

Today, the Claude M. Lightfoot papers [manuscript], 1950–85, n.d. (bulk 1969–85) can be accessed through the Abakanowicz Research Center, which is free to visit. The materials include correspondence, speech and manuscript notes, publicity information, reviews of his books, clippings and copies of Lightfoot’s newspaper columns in the Chicago Courier, and sound recordings of speeches by and about Lightfoot.

Lightfoot’s life, personal and professional, is chronicled in his autobiography, Chicago Slums to World Politics: Autobiography of Claude M. Lightfoot.