This blog post has been adapted from an essay by CHM intern Bella Santos, based on her work in the summer of 2022 around the printmaker Carlos Cortéz and the work of student activists at the Chicago History Museum.

In September 2019, Anton Miglietta, a history teacher at Instituto Justice and Leadership Academy (ILJA) in Pilsen, brought his class—learning about marginalized communities in Chicago—to the Chicago History Museum. On their trip, the students were met with very few artifacts or stories relating to Latino communities in the Museum. Soon after, the students organized protests and a social media campaign to express their anger about the lack of Latino/a/x history within CHM. The Museum held a meeting with the students and agreed on broadening its content to reflect Chicago’s population and creating an exhibition showcasing Latino culture.

When CHM brought me on as an intern, a main focus was how to appropriately represent an unrepresented community in the Museum. Historical erasure of minorities is a problem within archival institutions; CHM is no exception. Latinos make up 29% of Chicago’s population—a significant portion of the city. A city museum should reflect that city’s changing demographics—past and present. One way to do this is to use recent events to connect the stories of the past to many populations. Latinos are one of these groups.

Carlos Alfredo Koyokuikatl Cortéz (1923–2005), a Latino artist from Pilsen, is one person from a long list of underrepresented Latino activists and artists in Chicago’s history. Cortéz’s contributions to his community in Pilsen, the Chicagoland area, and the entire country is an example of someone who, like the students of IJLA, used his voice to spread a message of equality.

Carlos Alfredo Koyokuikatl Cortéz was born in Milwaukee on August 13, 1923. He grew up in a politically active family. His father, Alfred E. Cortéz, was a member of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) labor union, and his mother, Augusta Cortéz, was a member of the Socialist Party of America. Carlos grew up in Milwaukee, one of the epicenters of labor, racial, and civil rights debates in the 1960s and 1970s and then moved to Chicago and continued the family enterprise of political activism.

Cortéz was among the many men drafted into the army after the bombing of Pearl Harbor (1941), but he opposed the impending fights. Rebecca Meyers, permanent collection curator at the National Museum of Mexican Art, described his opposition to the draft as being against the “common man fighting the common man on foreign soil.” As a conscientious objector, Cortéz spent 18 months in prison.

The façade of the Mexican Fine Arts Center Museum, which became known as the National Museum of Mexican Art in 2006. Image courtesy of Carlos Tortolero

The opening of the Mexican Fine Arts Center Museum in 1987. Chicago mayor Harold Washington is in the right foreground with the red tie. Image courtesy of Carlos Tortolero

Cortéz’s political views translated into his artwork. He was inspired by José Guadalupe Posada, a popular Mexican lithographer famous for his pieces featuring political and social problems. Cortéz worked with fellow artist Leopoldo Mendez to create prints. In my interview with Meyers, she discusses the works of both artists and says,

They never destroyed the blocks that produced their prints. It was a way for Carlos to spread the word, to spread his artwork to as many people as he could. They were never interested in selling the prints or the blocks, it was all about the message.

Cortéz’s printing press was his form of mass, social, and fast media. Making his artworks readily available for anyone was his way of spreading his messages and increasing awareness about police brutality, political events, and personal reactions to global events.

Cortéz’s printing press. Photograph by CHM staff.

Among the events Cortéz responded to through his “mass media” art were a print titled “We Serve and Protect,” depicting police brutality, to bring awareness to the injustices that minority communities experienced, which he printed and distributed at the 1968 protests of the Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

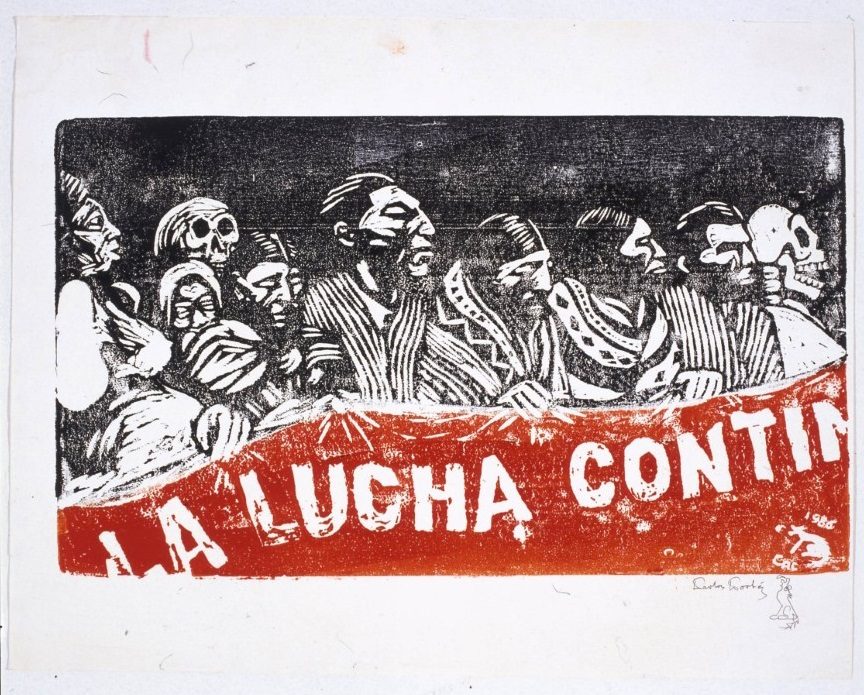

Carlos Cortéz, La lucha contínua / The Struggle Continues, 1986, woodcut, N.N., 17 5/8” x 21 5/8” (paper size), National Museum of Mexican Art Permanent Collection 1997.1, Gift of Carlos Cortéz, photo credit: Kathleen Culbert-Aguilar

Another of his recognizable pieces, titled “La Lucha Continua” (“The Struggle Continues”), reflects his experiences being a part of the IWW, and the case of five miners who were killed during the 1927 Columbine mine protests in Colorado. The protests started in response to and in solidarity with the wrongfully accused and murdered Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, with miners from the Rocky Mountain Fuel Company striking to improve the wages and working conditions of the workers. In 1989—62 years later—Cortéz went to the graves as a representative for the IWW to scatter the ashes of the last deceased miner, and he created “La Lucha Continua” in response to the injustices the laborers experienced. Workers’ struggles and Cortéz’s work convey a message of equality that is shared with other acts of protest.

Jair Urier Ramirez, a student at IJLA during the 2019 protest of CHM described his experiences to me. One notable thing he said was this,

I have calluses on my hands and bags under my eyes, you know? These are things that I would like to tell, my story, you know? And as someone who works with brown people every day, I think that’s something important to us. Why? Because we have different stories, and I think that was the ultimate essence of our project. And I say essence because that’s really how it was. Let us tell our stories and don’t stereotype us.

Ramirez is right that the upcoming Latino/a/x exhibition is including Latino communities and giving the right recognition to the right people. From my perspective, as a Latina, throughout this whole internship I saw how meaningful their protest was and how powerful it was to see people unite for a cause that adults had not taken action on. There is no singular way to solve societal dilemmas. We can only start by advocating for one another, and I do think this internship, as new as it is, is a great step towards change.

An undated photograph of NMMA president Carlos Tortolero touring the museum with then Senator Barack Obama.

When I first started, I had no idea what to expect, but as I interviewed more people and asked questions, it became clear how unifying this project is. It was enlightening to see how my research connected to Carlos Cortéz and his accomplishments with his artwork, the students with their protest, and me with my small contribution to this exhibition.