As Chicago’s 2024 Democratic National Convention (DNC) approaches, the news seems relentless with its coverage. How have past conventions been covered and viewed by the public? The upcoming 2024 DNC presents a perfect opportunity to look back at how the media influenced the perception of these events.

1940

The atmosphere of the 1940 convention was initially unusually quiet and controlled. President Franklin D. Roosevelt had the support of the public for an unprecedented and controversial third term, but the silence about his candidacy rendered news reporters and delegates uncertain about the convention’s direction.

Events aimed at influencing public opinion were mounted at the DNC, with the most (in)famous of these being the “voice from the sewers,” orchestrated by Chicago mayor Edward J. Kelly. In the silence following FDR’s announced desire to avoid reelection, a mysterious voice from the crowd boomed, “WE WANT ROOSEVELT.” Delegates and Kelly-planted demonstrators joined in, sparking a 45-minute hubbub and turning an initially dull convention into a “conflagration,” according to the Chicago Defender. FDR was overwhelmingly renominated by the convention delegates and reelected by the American public.

1940 DNC at the Chicago Stadium in Chicago, July 15, 1940. ST-17605664, Chicago Sun-Times Collection, CHM. Various newspapers reported on the event with vastly different opinions. For example, The Washington Post claimed it “saved [the convention] from dropping dead of acute ennui,” and Life Magazine decried it as “one of the shoddiest and most hypocritical spectacles in its history.”

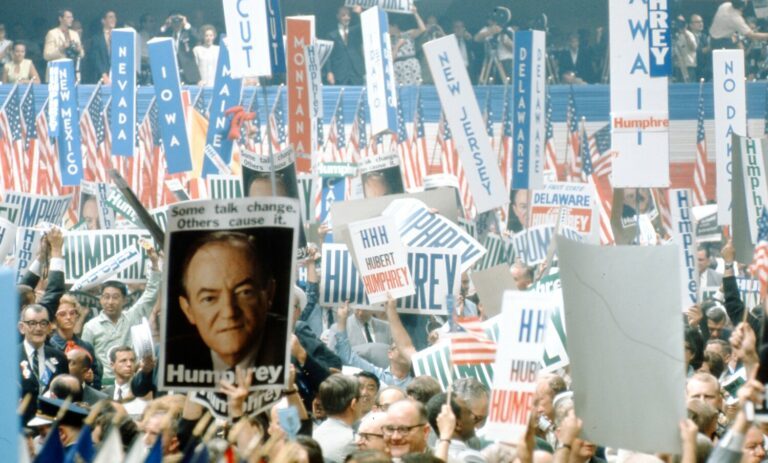

1968

If newspapers controlled the narrative in 1940, television ruled in 1968. When 10,000 Chicago Police Department (CPD) officers and 6,000 Illinois National Guardsmen attacked anti-Vietnam War protestors across the city, 83 million people watched in horror. Inside the convention, news reporters and delegates were assaulted by police, live on camera. News channels across the world decried the violence they witnessed.

Views of the 1968 DNC at the International Amphitheatre, Chicago, August 26‒29, 1968; ST-17102896-0017, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM. Hubert Humphrey became the nominee, but he lost the presidential election to President Richard Nixon.

However, City Hall used the media to orchestrate a counterattack justifying the CPD’s actions, and people began to doubt what happened. The Chicago Tribune praised Daley as “saving” the convention “from utter chaos,” and the New York Times emphasized that Daley received support from 90% of Chicagoans. A few weeks later, the Tribune ran a story on FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover’s interpretation of events, in which he criticized the media for magnifying “so-called ‘police brutality.’” Thus, while the media provoked outrage, it also covered the cracks it had revealed.

1996

Leading up to the 1996 convention, the public was aware of the comparisons between ’68 and ’96. Protests meant to emulate the ’68 demonstrations gathered in Grant Park and outside the newly built United Center, and police were trained to head off these protests at even higher numbers than before. Democrats took great pains to placate concerns, leading to headlines like “TALE OF 2 CONVENTIONS: The 1968 Gathering May Have Been The Worst Of Times, But Democrats Say 1996 Will Be The Most Harmonious Ever.”

Exterior view of the United Center during preparations for the 1996 DNC, June 25, 1996, Chicago; ST-30002442-0080, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM. Democrats took great care to soothe concerns that this convention would become the chaotic 1968 DNC and played up inter- and intra-party unity. President William J. Clinton was renominated and would go on to win another term in office.

Since the ’68 DNC, conventions had become more family-friendly than firebrand. Speakers shifted from politicians to actors and athletes, and there was more coverage of the original Broadway cast of Rent performing “Seasons of Love” than the protests just outside. The Chicago Tribune attributed this dramatic difference to homogenized political parties with no serious issues to debate, while Florida’s Sun-Sentinel thought it represented “society’s shift from turbulent idealism to cautious cynicism.” This appeal to a wider audience demonstrated, more than anything, how the ’96 convention played to a safe TV spectacle.

2024

Each of these previous DNCs and today’s media coverage will influence our perception of the event. Will we see strategic media ploys coordinated from top party officials? Unpredictable protests that shake our political system? A trouble-free, carefully calibrated TV spectacle? In August, we will certainly find out.

Preparations at the United Center for the 1996 Democratic National Convention; ST-30002442-0066, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Chicago has been the nation’s most popular political convention city, in part because of its geographic centrality. Learn more about past political nominating conventions and find more CHM resources on the history of these conventions.

About the Authors

Caroline Hugh is a Chicago History Museum Curatorial Research Intern for Summer 2024. She is a current University of Chicago student in History, Urban Planning, and Law, Letters, and Society.

Tori Harris is a Chicago History Museum Curatorial Research Intern for Summer 2024. She is a current University of Chicago student in Anthropology and Creative Writing.

Sources

- Turner Catledge, “Roosevelt Dominates Convention at Chicago: Convention Host,” The New York Times, July 14, 1940, sec. The Week In Review.

- “CBS 2 Vault: Live at the 1996 Democratic National Convention after President Clinton’s Acceptance Speech – CBS Chicago,” CBS News, March 30, 2022.

- Richard F. Ciccone, “Reflections on a Dying Tradition: The ’96 Conventions Were Little More Than Wakes for a System That Has Been on Life Support for the Last 20 Years,” Chicago Tribune, August 30, 1996, sec. The Democratic Convention.

- Bernard F. Donahoe, Private Plans and Public Dangers: The Story of FDR’s Third Nomination (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1965).

- Susan, Dunn. 1940: FDR, Willkie, Lindbergh, Hitler–The Election amid the Storm (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013).

- Willard Edwards, “’68 Convention Seen as Last of a System: Chicago Democratic Convention of 1968 Has Far Reaching Political Consequences,” Chicago Tribune, September 1, 1968.

- Evening Standard, August 29, 1968.

- “The Daley Report,” Fifth Estate Magazine, Sept. 19-Oct. 2, 1968.

- Donald Janson, “Daley Demands Television Time to Defend Police,” Special to the New York Times, September 4, 1968.

- “President Roosevelt Answers a Call to Run for a Third Term,” LIFE, July 29, 1940.

- Richard Moe, Roosevelt’s Second Act: The Election of 1940 and the Politics of War. Pivotal Moments in American History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013).

- David Nitkin, “Tale of 2 Conventions: The 1968 Gathering May Have Been the Worst of Times, But Democrats Say 1996 Will Be the Most Harmonius Ever,” Sun Sentinel, August 25, 1996.

- Reprints from the World Press [on Chicago during the Democratic Convention], vol. 6 (St. Louis: Focus Midwest, 1968).

- Richard J. Daley. “Mayor Richard J. Daley Inaugural Address, 1967,” Chicago Public Library, April 20, 1967.

- “Vox Populi,” Washington Post, July 20, 1940.

- Enoc P. Waters, “Race Democrats Represented By 25 On Convention Floor: New York Democratic Standard Bearers Prominent Leaders at 28th Democratic National Convention,” The Chicago Defender (National Edition), July 20, 1940.

- James Yuenger, “Hoover Lauds Chicago Cops: Defends Actions in Hippie Clashes,” Chicago Tribune, September 19, 1968.

Comments