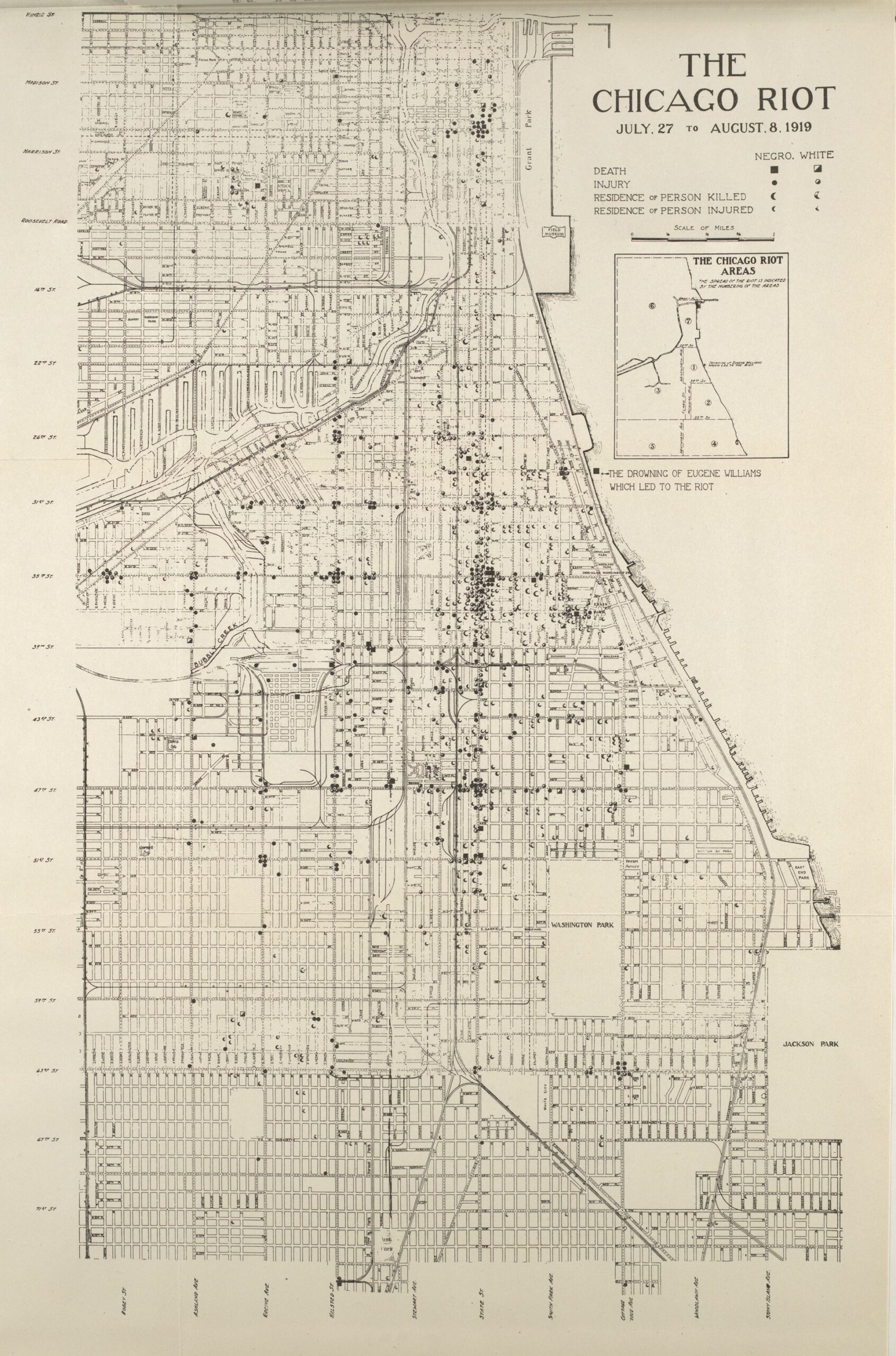

This Saturday marks one hundred years since the Chicago Race Riot that began on July 27 and ended on August 3, 1919. In this photo essay, CHM assistant curator Julius L. Jones recounts the events of that tumultuous week, as well as the legacy of activism that came from it. All images are from the collection of the Chicago History Museum. Warning: The fifth image is graphic in nature. Viewer discretion advised.

On Sunday, July 27, 1919, thousands of Chicagoans sought relief from the brutal heat on the shores of Lake Michigan. Among them was Eugene Williams, a seventeen-year-old African American. When he and his friends inadvertently drifted across an invisible line that divided the waters by race, a group of whites, insulted by such an act, began throwing stones at them, one of which struck Williams, causing him to drown. In the racial powder keg that was Chicago, his murder was the spark that ignited it during what became the Red Summer of 1919.

After the drowning of Eugene Williams, the police refused to arrest the white man who was considered responsible for his death. As the crowd grew, the tension escalated, and the fighting began. CHM, ICHi-030315; photograph by Jun Fujita

The violence that started at the beach spread through Chicago’s Black Belt on the South Side, especially in residential areas surrounding the Union Stock Yard. CHM, ICHi-040053

The front page of the Chicago Defender on August 2, 1919, announced the turmoil in the city and listed the names of those who were slain and injured. CHM, ICHi-040222

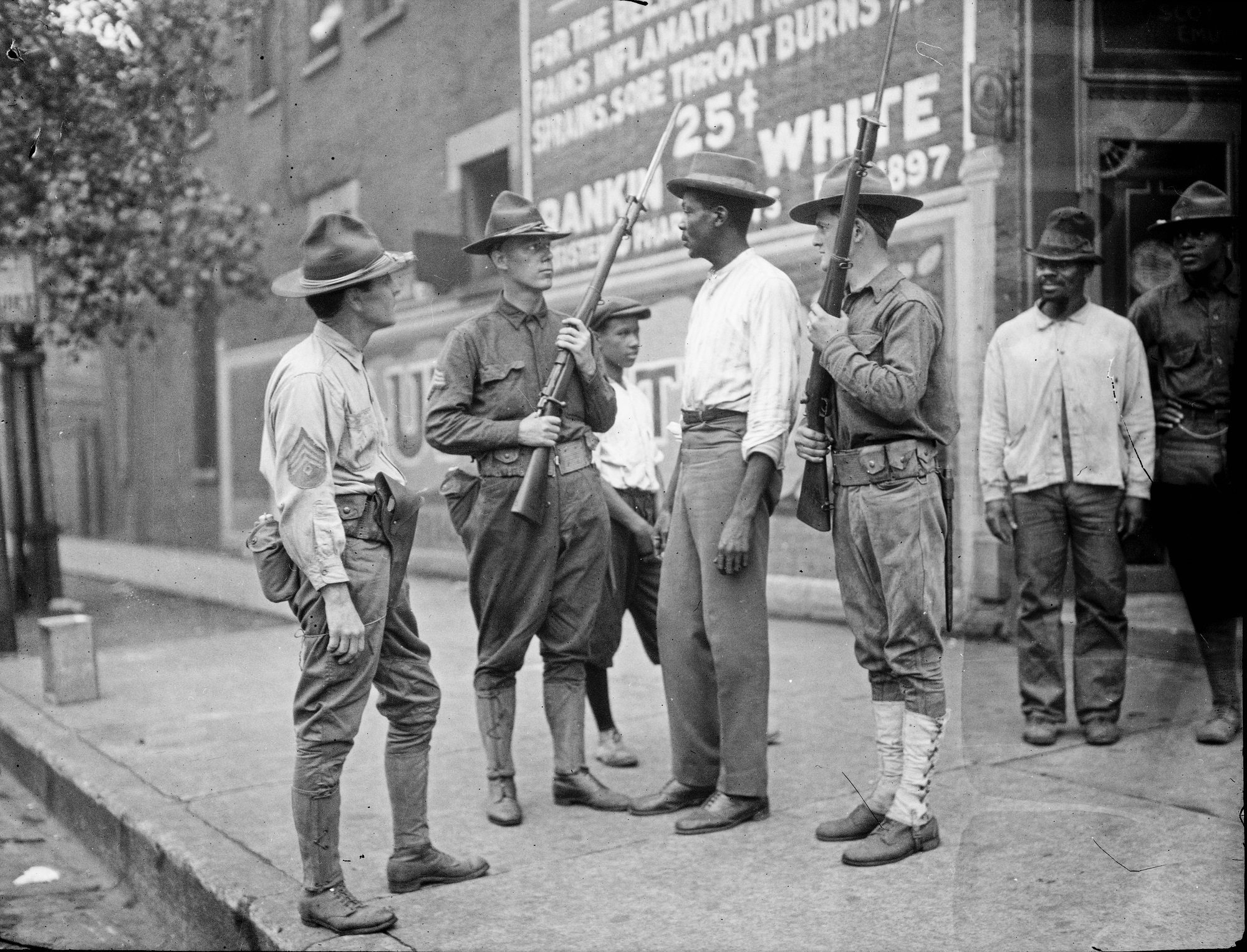

The police force, owing both to understaffing and the open sympathy of many officers with the white rioters, was ineffective. Only the long-delayed intervention of the Illinois National Guard brought the violence to a halt. CHM, ICHi-065478; photograph by Jun Fujita

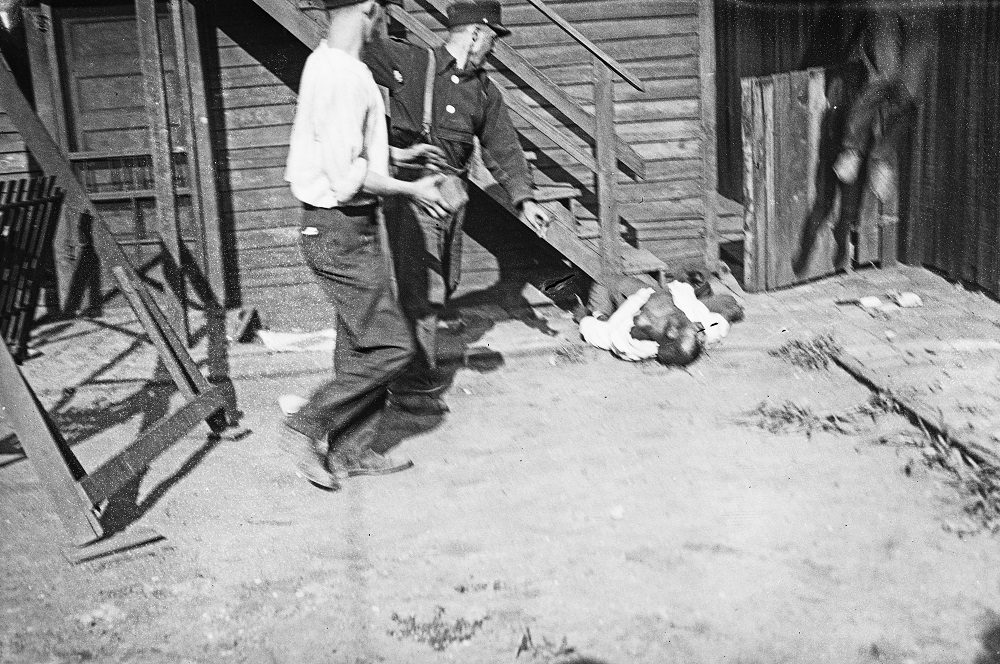

Two white men stone an African American man during the riot. White gangs intentionally went into black neighborhoods to wreak havoc. CHM, ICHi-022430; photograph by Jun Fujita

Rioters ranged from children to adults. Here, a group stands in and around a home that was vandalized and looted. CHM, ICHi-065487; photograph by Jun Fujita

The Riot’s Legacy

After seven days of shootings, arson, and beatings, the Race Riot resulted in the deaths of 15 whites and 23 blacks with an additional 537 injured (195 white, 342 black). Since then, a century of African American activism has challenged the racism and social hypocrisy that allowed those responsible for Eugene Williams’s death to elude justice. Activists continue the fight against racial discrimination in Chicago and the United States.

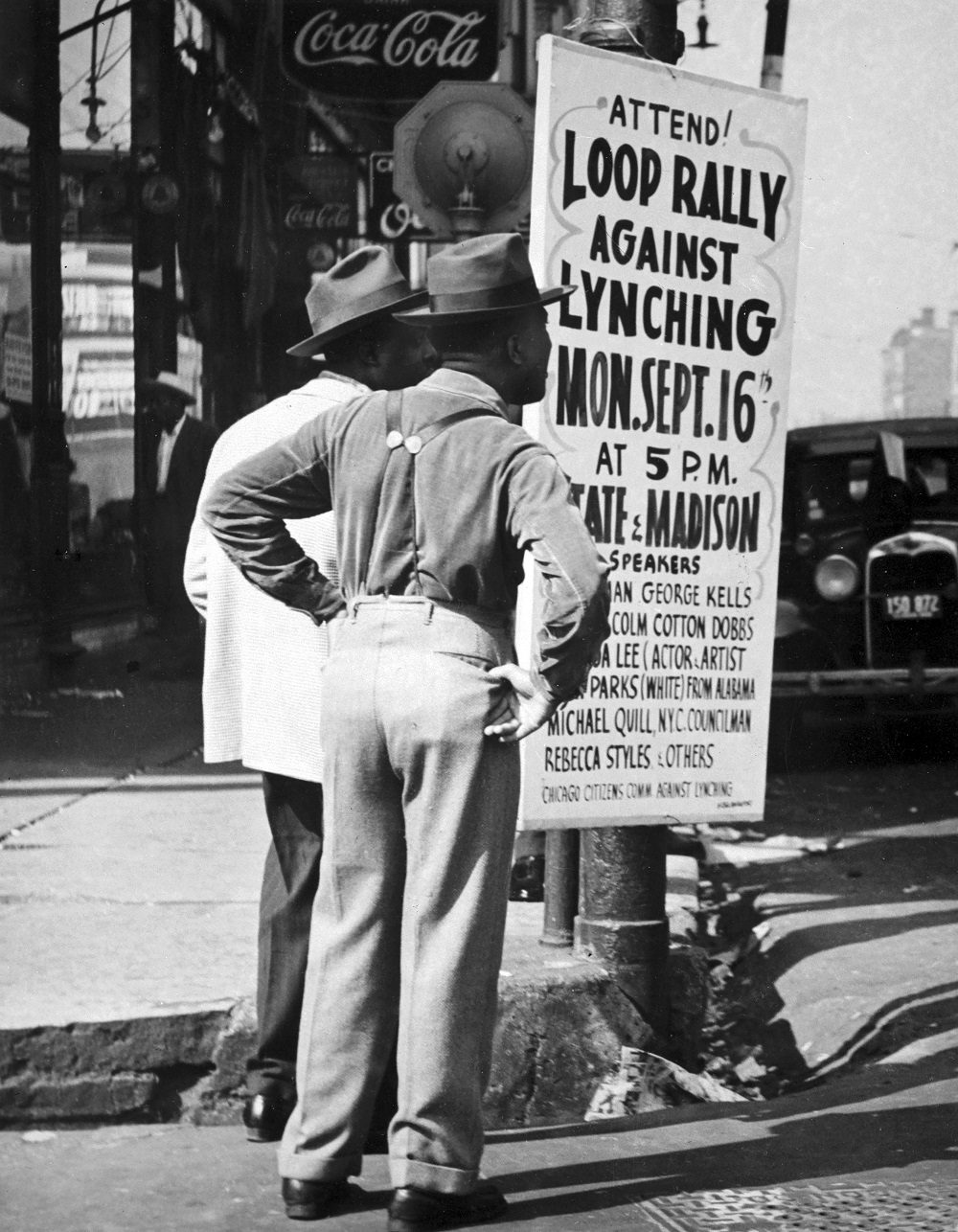

The aftermath of World War II saw a revival of white attacks on African Americans. Here, two men at 31st Street and Cottage Grove Avenue stand next to a sign for a rally against lynching, August 1946. CHM, ICHi-003616; photograph by John F. Weld

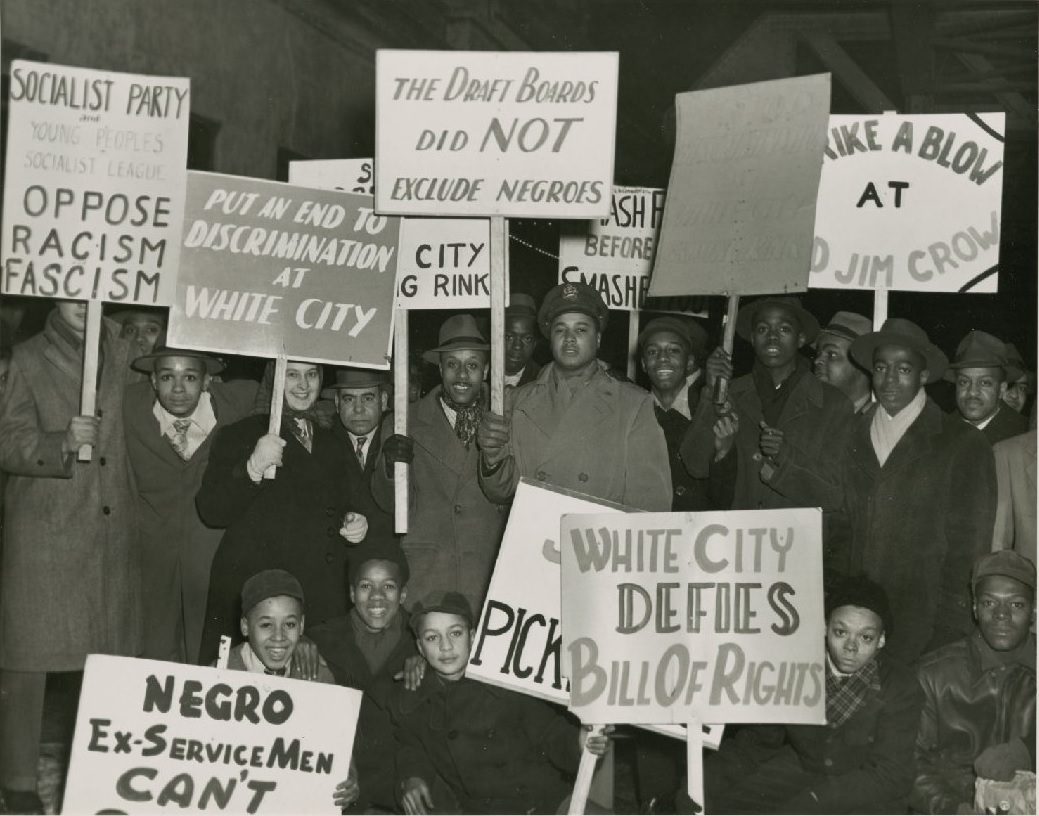

Protests throughout the 1940s and 1950s sought to break down racial barriers in housing, public accommodations, and recreational activities. This one took place at the White City Roller Rink, 63rd Street and South Parkway (renamed Martin Luther King Drive in 1968), Chicago, 1946. CHM, ICHi-019601; photograph by John F. Weld

In the 1960s, the Chicago community of Ashburn saw significant racial strife over school desegregation. This open housing march took place near Bogan High School, August 12, 1966. CHM, ICHi-077756; photograph by Declan Haun

The Chicago History Museum is a partner institution for Chicago 1919: Confronting the Race Riots, a year-long initiative to heighten the 1919 Chicago race riots in the city’s collective memory, engaging Chicagoans in public conversations about the legacy of the most violent week in Chicago history.

Join the Discussion