What is redlining? A form of discrimination. Simply put, it’s the practice of arbitrarily denying or limiting financial services to specific neighborhoods, generally because its residents are people of color or are poor. Like other forms of discrimination, it has inflicted long-lasting damage.

While discriminatory practices had long existed in the banking and insurance industries, the term came into use in the 1930s when the New Deal’s Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) instituted a redlining policy by developing color-coded maps of American cities that used racial criteria to categorize lending and insurance risks. New, affluent, racially homogeneous housing areas received green lines, while Black and poor white neighborhoods were often indicated by red lines denoting their “undesirability.”

In Chicago, the effects of redlining became obvious after World War II. Without bank loans and insurance, redlined areas lacked the capital essential for investment and redevelopment. As a result, suburban areas received preference for residential investment at the expense of poor and minority neighborhoods in the city. The relative lack of investment in new housing, rehabilitation, and home improvement contributed significantly to the decline of older urban neighborhoods and compounded Chicago’s decline in relation to its suburbs.

Redlining’s negative effects remained largely unrecognized by policymakers until the mid-1960s when the Fair Housing Act of 1968 was passed and then with the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act of 1975. Unsatisfied by the practical results of these laws, community activists in Chicago spearheaded further reform, leading the nation in identifying and addressing the redlining issue.

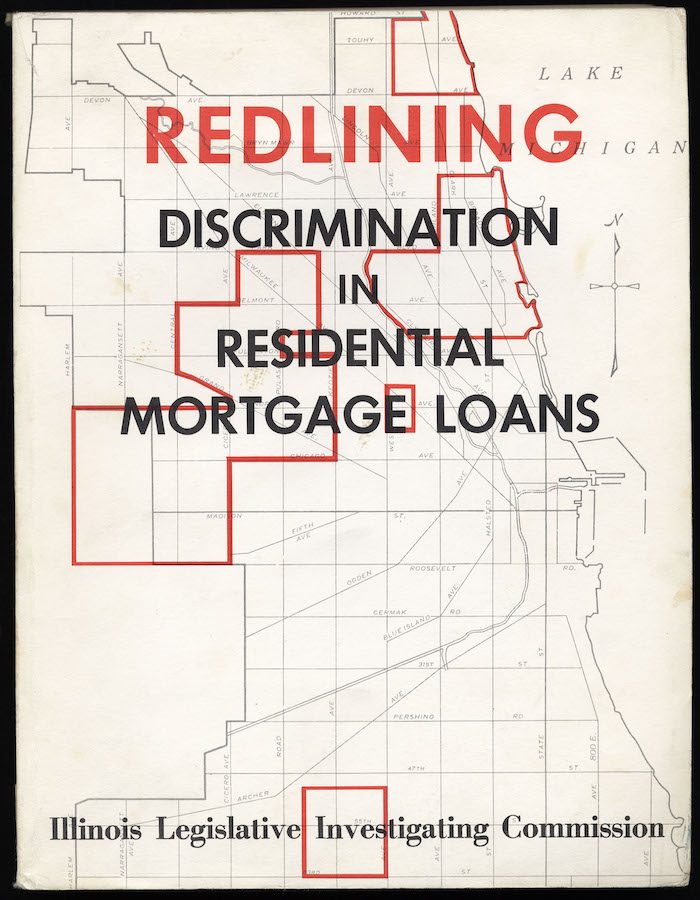

The cover of “Redlining: Discrimination in Residential Mortgage Loans,” a report by the Illinois Legislative Investigating Commission, 1975. CHM, ICHi-037471

The cover of “Redlining: Discrimination in Residential Mortgage Loans,” a report by the Illinois Legislative Investigating Commission, 1975. CHM, ICHi-037471

In the early 1970s, the Citizens Action Program, a crossracial group of community leaders from the South Side, developed a strategy of “greenlining” by asking residents to deposit savings only in banks that pledged to reinvest funds in urban communities. Chicago organizers were also instrumental in lobbying Congress to pass the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) in 1977, which required banks to lend in areas from which they accepted deposits. The law had limited effect until the National Training and Information Center in Chicago, led by Gale Cincotta, put public pressure on Chicago banks to lend to distressed neighborhoods. Cincotta’s group successfully negotiated $173 million in CRA agreements from three major downtown banks in 1984, settlements that served as models for other cities.

Additional Resources

- Learn more in the Encyclopedia of Chicago.

- A community activist from Chicago’s Austin neighborhood, Gale Cincotta was an expert on discrimination in mortgage loans and its effects in Chicago and other cities. Learn more about her work on issues of housing and employment in her interviews with Studs Terkel.