CHM senior curator Olivia Mahoney writes about a Chicago innovation that helped the city recover from the 1871 fire in a surprisingly beautiful way.

This year marks the 146th anniversary of the Great Chicago Fire that blazed through the city from October 8 to 10, 1871. One of the worst urban fires in American history killed approximately three hundred people, left thousands more homeless, and utterly destroyed the city’s central business district. Previously, the common building materials of stone, iron, and brick were thought to be fireproof, but they were no match for the fire’s intense heat. Yet, as the old saying goes, something good can come out of tragedy, and in this case, the good turned out to be Chicago’s innovative use of terra-cotta to fireproof buildings.

The backside of a sample tile (upper), c. 1904–29, made by one of Chicago’s leading companies shows the porous nature of terra-cotta. The front side (lower) has a cream-colored glaze. Photograph by CHM staff

Terra-cotta, or “baked earth” in Latin, is a clay-based unglazed or glazed ceramic with a porous texture. It had been used as a building material for centuries elsewhere in the world, but not in the United States until the 1870s. Several Chicagoans have been credited with the idea of using terra-cotta as fireproofing: George H. Johnson, manager of Architectural Iron Works; Johnson’s associate, the architect John M. Van Osdel; and architect Sanford E. Loring in association his colleague Peter B. Wight. We may never know who actually came up with the idea but there is no doubt that Chicago terra-cotta revolutionized the building trade and made modern skyscrapers possible. Indeed, the skyscraper’s interior iron frame had been developed in New York during the 1850s, but its use remained limited due to its inability to withstand high heat. All of that, however, changed with Chicago terra-cotta, which was made from an abundant source of local clay.

This terra-cotta block is from the upper frieze of the Troescher Building designed by Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan and produced by the Northwestern Terra Cotta Company in1884. CHM, ICHi-092994

Three companies dominated the industry: the Chicago Terra Cotta Company, established in 1868 and led by Loring; True, Brunkhorst & Company, established by three former employees of Chicago Terra Cotta in 1877 and later known as the Northwestern Terra Cotta Company; and the American Terra Cotta & Ceramic Company founded by William Day Gates in 1881. These companies made both terra-cotta tiles for fireproofing interior frames and exterior terra-cotta blocks for façades, while smaller companies, such as the Wight Fireproofing Company and the Illinois Terra Cotta Lumber Company specialized in producing interior tiles.

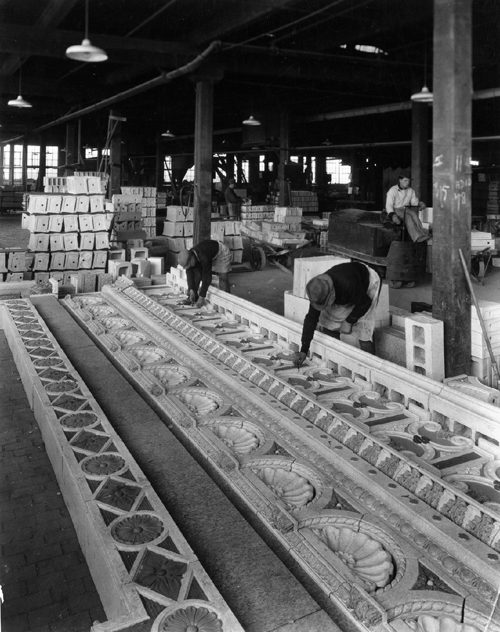

An undated photograph of the Northwestern Terra Cotta Company’s fitting department as they label terra-cotta architectural blocks by hand. CHM, ICHi-62923

Thus, terra-cotta allowed architects to design buildings that were taller, safer, and more beautiful, given the material’s malleable qualities that allowed for elaborate ornamentation. During the 1880s, Chicago’s building and terra-cotta industries flourished. A city ordinance passed in 1886 requiring all buildings over ninety feet high to be fireproof furthered the industry’s fortunes. Chicago leading architects and firms, such as William Le Baron Jenney, Burnham & Root, and Adler & Sullivan, used terra-cotta extensively, giving Chicago a distinct look and feel with earthy red and cream-colored buildings. Indeed, terra-cotta became so closely associated with Chicago that the city’s first flag of 1893 featured its colors.

Dutch immigrant architect Alfred Jensen Roewad used terra-cotta colors in designing Chicago’s first flag for the 1893 world’s fair. The cream colored “Y” represents the three branches of the Chicago River and how they divided the city into the North, South and West Sides, represented by the earthy red backdrop. The flag remained in use until the city adopted a two-star version of the current flag in 1917.

Chicago architects continued to use terra-cotta well into the twentieth century, creating such spectacular examples as the Railway Exchange Building, the Wrigley Building, the Carbide & Carbon Building, and the Chicago Theatre, which still stand today in glorious tribute to an important innovation that rose from the ashes of the Great Chicago Fire.