At the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition (WCE), Polish Chicagoans supported their homeland‘s participation despite colonizing empires, mainly Russia and Germany, resisting an independent Polish presence. Polish artists, musicians, and industrialists still displayed and performed for an international audience.

World’s Columbian Exposition Polish Day ribbon, Chicago, 1893. Collection of the Chicago History Museum, X.3005.2005

At the time, what had once been the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was consumed by the Russian, German, and Austro-Hungarian Empires, so Polish people had no independent state beyond a few territories, including Congress Poland. Nevertheless, Polish Chicagoans met in spring 1893 to discuss how to help visitors from Polish lands and to organize a Polish Day for the fair. The major Polish American organizations at the time—the Polish Roman Catholic Union of America and the Polish National Alliance—supported these efforts.

Informal portrait of Ignace Jan Paderewski standing with a group in Chicago, 1922. DN-0074496, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

Although overall Poland’s presence in the exhibits was slight, there were opportunities for several Poles to show their talents. On the second day of the fair, May 2, the renowned Polish pianist Ignacy Jan Paderewski performed with the fair’s orchestra. Then on August 4, 1893, Polish Chicagoan Maximilian Drzemala gave a lecture on Polish art, followed by an inauguration of the Polish art section at the Palace of Fine Arts. This was the first exhibition of Polish art in the United States and featured 122 paintings from 59 artists.

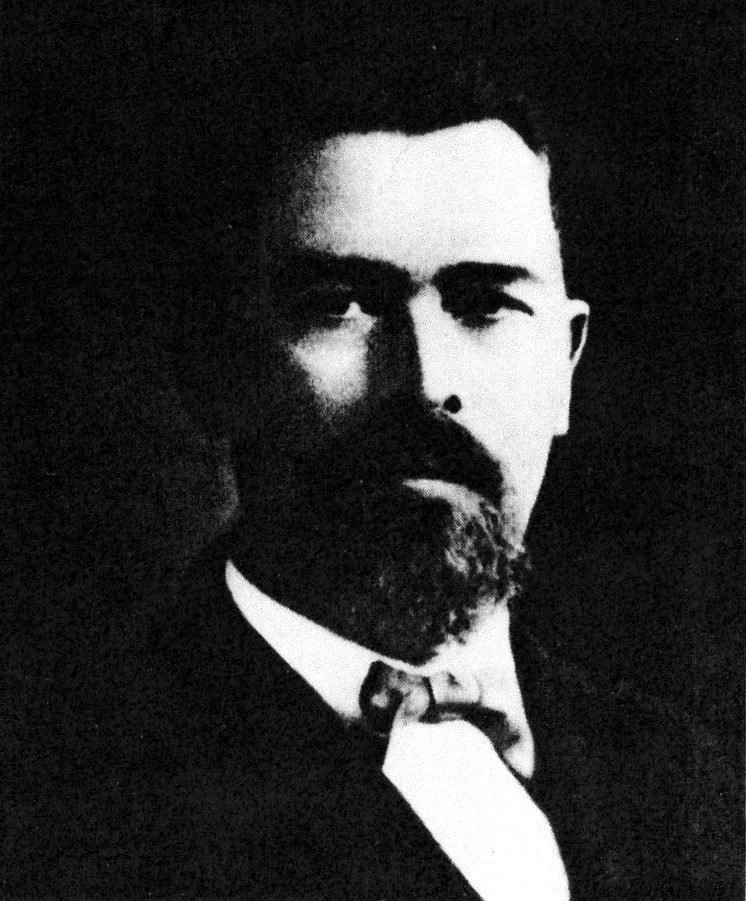

Piotr Kiołbassa, n.d. (Later published in Polska w Ameryka by Jan Drohojowski.)

The biggest impact on the fair came on Polish Day. On Saturday, October 7, 1893, thousands of Polish residents from all over the city took part in a procession to the site of the WCE. They gathered at Jackson Boulevard between Wood Street and Paulina Street. Piotr Kiołbassa served as the parade’s grand marshal. He had been elected city treasurer in 1891, the first Polish Chicagoan to serve in such a position. At 10 a.m., Kiołbassa led the parade of uniformed cavalrymen, carriages, bands, and floats toward Michigan Avenue. Many participants were members of Polish fraternal societies and community groups.

Chicago mayor Carter Harrison also participated, riding in a carriage behind Kiołbassa and Captain Joseph Nepieralski, an active participant in the 1830 uprising. The group marched toward Michigan Avenue and then down to the review stand at the Columbus statue. They proceeded to Twelfth Street and doubled back to Van Buren Street before finally going by train to Jackson Park.

The sixteen floats in the parade primarily depicted historical events. In his book American Warsaw, Dominic A. Pacyga writes that the idea behind all the floats was to “convinc[e] the city, and in turn, the world, of the righteousness of Poland’s call for the restoration of its independence” (p. 21). The last float in the parade was from St. Casimir’s Parish and was titled “The Resurrection of Poland.” It displayed a broken prison gate with a female figure representing Poland emerging from it with several “dead” Russian, Austrian, and Prussian soldiers lying around.

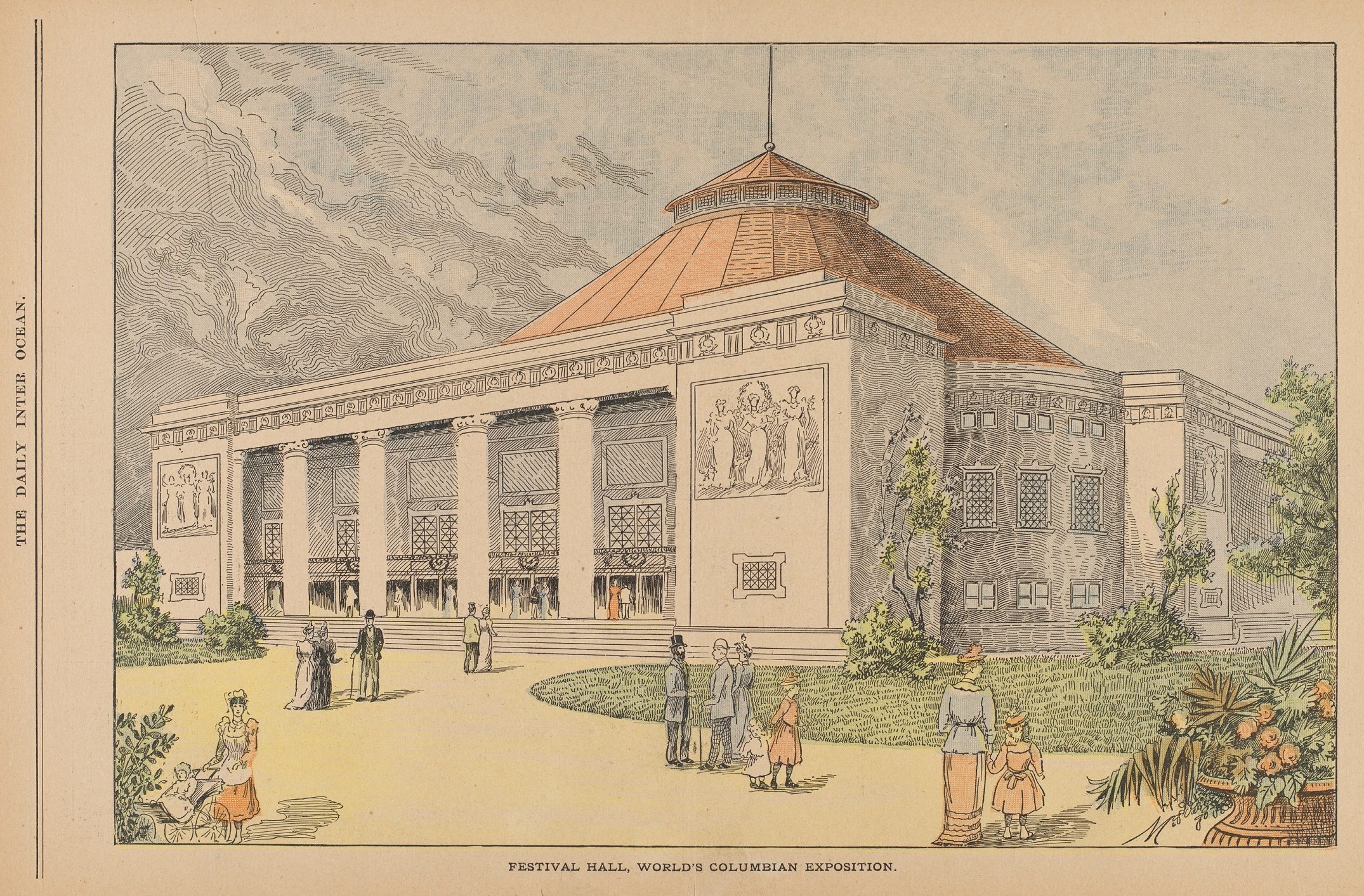

Color illustration titled “Festival Hall, World’s Columbian Exposition,” Chicago, 1893. Published in The Inter Ocean Illustrated Supplement. CHM, ICHi-089488

The parade ended at Festival Hall with remarks from Polish Day Central Committee president S. Słominski, Judge Michael A. LaBuy, and Mayor Harrison. Between eight and ten thousand people attended the ceremony. October 7 was one of the most attended days of the entire fair, with various reports claiming twenty-five to fifty thousand Polish Americans in attendance.

See the Polish Day ribbon, as well as items from the 1933-34 A Century of Progress world’s fair, in our Back Home: Polish Chicago exhibition.