Algae Guzman is a graduate student at University of Illinois Chicago who has been interning with CHM curator of civic engagement and social justice Elena Gonzales for our upcoming exhibition Aquí en Chicago. Part of their work includes researching Latino/a/x histories of Chicago.

On May 27, 2021, Jesús “Chuy” Negrete passed away at the age of 72 in Chicago. Negrete was born in San Luis Potosí, Mexico. Early in life, he and his family immigrated to the United States in search of work, briefly settling in the Rio Grande Valley in south Texas, where I grew up. This particular region was known as el valle magico, the Magic Valley, due to its fertile soil and high production of citrus and other crops. By the time Negrete was seven years old, his family had resettled in South Chicago where his parents found other employment opportunities.

Throughout his life, Negrete drew inspiration from the Civil Rights Movement, was highly involved in the Chicano Movement, and fought for laborers’ rights. His most powerful form of protest was through songs called corridos. Corridos are a genre of Mexican folk music, and their form is a mechanism for storytelling. Corridos are most popularly used to tell stories of oppression, immigration, romance, and/or life histories. Negrete honed his songwriting skills to tell the stories of Latino/a/x individuals from inside and outside of Chicago.

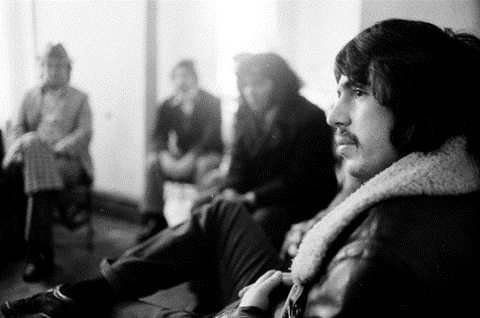

Negrete on stage with guitar during a Teatro del Barrio performance, Chicago, c. 1970. Photograph by Louis Guadarrama Jr. Image courtesy of the Southeast Chicago Historical Society and Museum, 1993-017-20.

When deciding what my research contribution would be for the upcoming Aquí en Chicago exhibition, I strategically tried to find a topic that would support the research needed to complete my master’s thesis at the University of Illinois Chicago. In a surprising turn of events, my research on Negrete helped me find other talented Tejano and Conjunto musicians who crafted and performed corridos. Most of them rose to fame with origins in the Valley, such as Narciso Martínez, Lydia Mendoza, Chelo Silva, and Valerio Longoria.

Martínez immigrated to the United States as an infant from Reynosa, Tamaulipas, Mexico, and is most commonly known as the father of conjunto music—another musical genre that at times uses the lyrical structure of corridos alongside instruments like the bajo sexto (sixth bass guitar) and the acordeón (accordion). Mendoza, while born in Houston, Texas, migrated to and from Mexico with her family accompanying her railroad worker father. Silva, born in the lower Rio Grande Valley, went so far as to achieve international recognition in Mexico and South America. Longoria learned how to play the accordion by watching Martínez during breaks while employed in farm work together, then spent years in Chicago touring solo. These musicians, unlike Negrete, did not concentrate on lyrical production that highlighted local or national issues.

Walkout at Republic Windows and Doors in Goose Island, as former employees picket the entrance due to not getting pension, vacation pay, and extended health care after the company closed without proper notification, December 8, 2008. STM-011368057, Tom Cruze/Chicago Sun-Times

In 2009, Negrete wrote and performed two songs, “For the People” and “Huelga,” for a radio documentary, Sí Se Puede, which told the story of Republic Windows and Doors and how the company abruptly closed in 2008, leaving its workers without health insurance, paychecks for hours worked, or jobs.

For the People

And so it came to be that on the fifth of December, one cold day

In the city of Chicago

At the Republic Window Company, they did say

Out on strike that fine ay

And they took over the factory

For those six long days

The people, the workers of the U.E., today

Huelga, huelga, huelga,

Huelga it means strike

Huelga, huelga, huelga,

Huelga, we had just begun to fight

Huelga

El corrido del U.E. strike

El día cinco de diciembre

Allá en la ciudad Chicago

Comenzaron su huelga

Y por seis días enteros

Los trabajadores agarraron la compañía

Era la República compañía de ventanas popular

Era la República ese día en Chicago no muy cerquita del mar

These two corridos told the story of how the workers formed a union and held a strike to combat the injustices they faced. Negrete also wrote songs like “Corrido del bracero,” detailing Mexican immigrants’ struggles in finding work in the United States and the difficult lives bracero workers faced.

Other Chicago residents have taken up guitars and penned their own corridos of events that are occurring around the city. Two brothers, Ignacio and Santiago Echevarría, known as “Los Dos de Michoacán” (The two from Michoacán), wrote two songs, “La emboscada” (The ambush) and “Corrido de Elvira Arellano,” about an undocumented mother who fled deportation and sought sanctuary in a church near Humboldt Park.

While Negrete and the Echevarría brothers used corridos to share the stories of their community, the US government has recently manipulated the musical genre. By creating their own corridos, the US government hoped to discourage migration into the US by telling stories of the dangers of migration in grueling ways. By dispersing these horrific migra corridos through Central American, Mexican, and US radio shows, the aim is to frighten potential migrants from ever making the journey. These songs are small forms of propaganda and part of a covert series of policies put in place to reduce the number of immigrants arriving in the country, otherwise known as prevention through deterrence.

Though the above corridos focus on heavy topics, not all do. Around 1924, a corrido was written about a tax law passed in Chicago that applied only to women with short hair.

Contribución a las pelonas

Atención pongan, señores,

de lo que la prensa ha hablado

en motivo de un decreto

que Chicago se ha implantado.

La mujer que esté pelona

pagará contribución

Mexicana o extranjera

sin ninguna distinción.

Tax on Bobbed Women

Attention, gentlemen,

The press is full of news

Because of a law decreed

In the city of Chicago.

All women with bobbed hair

Will pay a tax,

Mexican or foreigner

Without distinction.

Miss Betty Quick, Miss Elizabeth Carpenter, and Miss Polly Carpenter standing outside near a fence covered in plants, picking flowers, in Chicago, 1920. The Carpenters on the right have bobbed haircuts whereas Quick on the left has her hair in an updo. DN-0072316, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

Humor need not be absent from this genre; in fact, Negrete mastered the balancing act of embedding it into his act. When performing at the 2012 National Association for Chicana and Chicano Studies Conference, he opened with a joke. He recounted a story of someone telling him of the founding of the United States, starting at Plymouth and the thirteen colonies, stating George Washington was Negrete’s father. In response, Negrete stated, “I was reluctant to believe her, and so suddenly I raised my mano on the 16th of September and I told her if George Washington was my father, then why wasn’t he Chicano. . .” before launching into his corrido.

Chuy dedicated his musical career to uplifting stories that often went unheard. Negrete’s lyrical and performance intentionality can also be seen below in his corrido eulogy to Rudy Lozano.

Remembering Rudy Lozano

Spoken word:

. . . Rudy used to say

If you want to live forever

You can never live at all

It is only when you’ve accepted the fact that

you must die,

That you can truly life

Es mejor vivir de pie (It is better to live on your feet)

Que seguir viviendo de rodillas… (Than it is to keep living on your knees)

Singing:

. . . ¿Qué se cayó (What fell)

El ocho de junio? (The eighth of June?)

El compañero asesinado. (The assassinated friend.)

El compañero mexicano. (My Mexican friend.)

El compañero Rudy Lozano. (My friend Rudy Lozano.)

Rudy Lozano listens during a meeting at CASA (the Centro de Accion Social Autonomo, or the Center for Autonomous Social Action), Chicago, February 12, 1975. ST-40001425-0007, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

I find it fitting to end this article with a mention of the tocayo (namesake) high school responsible for the forthcoming Aquí en Chicago exhibition, the Rudy Lozano Instituto Justice and Leadership Academy. Through song and education, we can keep both these Mexicano Chicagoans alive.