This year, the Jewish festival of Sukkot began at sundown on Sunday, October 9, and ends in the evening of Sunday, October 16. CHM curator of religion and community history Rebekah Coffman explains the meaning and significance of the holiday and talks about an artifact in our collection that is inspired by it.

While Sukkot is a weeklong harvest celebration, it is also a time for remembering when Jews lived in temporary dwellings in the wilderness after escaping slavery in Egypt. In preparation, small outdoor huts (Hebrew: singular, sukkah; plural, sukkot) are built after the conclusion of Yom Kippur.

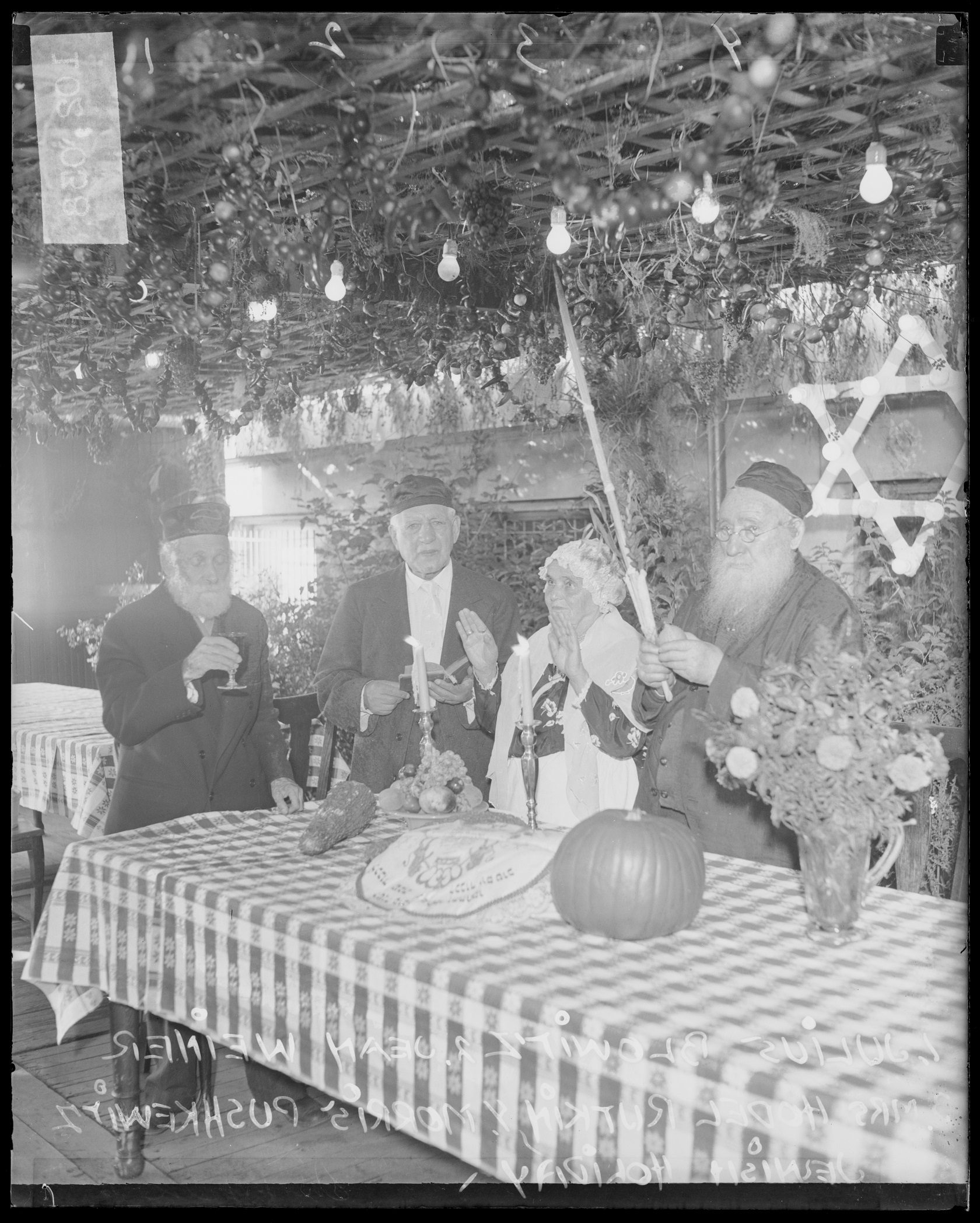

A Sukkot celebration at the Jewish Old People’s Home, Chicago, 1932. DN-0102038, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

The sukkah acts as a place of gathering, eating, celebrating, and communal remembering, as seen in this image of community elders gathering in a sukkah in 1932. As a temporary structure, it can also be a reminder of life’s fragility, and the sukkah’s thatched roof allows for reflection under the open sky. Another important element is the four species, which includes a bundle made of palm branch (lulav), willow (aravot), myrtle (hadassim), and a citrus fruit (etrog), sometimes called collectively the lulav. Imbued with symbolic meaning, the lulav is ritually waved while blessings are said inside the sukkah to set apart the time spent gathered within.

Berit Engen. Lulav in a sukkah tapestry. 2012. Linen. CHM Purchase, 2015.54.3.1.

These ritualistic elements are beautifully presented in Berit Engen’s weaving, Lulav in a sukkah (2012). Born in Norway, Engen immigrated to the US in 1985 and now resides in Oak Park, Illinois. Her work takes inspiration from her childhood experiences weaving and uses them to create concise tapestries as a form of personal reflection and expression. Created as part of her project Weft and D’rash: A Thousand Jewish Tapestries, the multiwork series combines craft with scriptural commentary by using abstracted colors, shapes, objects, and seasonal elements. She began the series in 2007 and has created 620 small tapestries to date, all measuring around 9”x7.” Engen compares the process to forming a haiku, in which the subject at hand is distilled to an essence of representation.

Lulav in a sukkah comes from the subseries “Holy Days II—What They Look Like,” which specifically explores celebrations throughout the Jewish ritual year. In describing the meaning behind these Holy Days, Engen writes, “While structured in commandments and traditions for celebration and observance that make us feel rooted, they stimulate and inspire our Jewish sensibilities with food, words, melodies, and ritual objects. Time is set aside for something larger than our individual selves in community with others.” In the tapestry, the yellow of the etrog, green of the lulav bundle, and orange-pink of the sukkah’s thatching are striking against a deep purple background, reminiscent of a dark night’s sky, and allude to this season of harvest and communal celebration.