In this blog post, CHM intern Rebekah Otto reflects on her experience working on CHM’s ongoing Afro-American Patrolmen’s League Oral History Project.

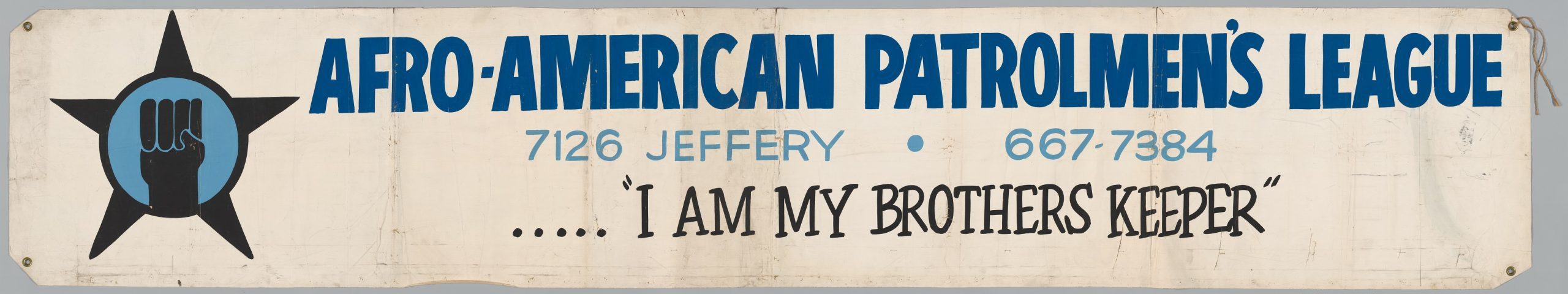

AAPL vinyl banner that reads, 1961–68. CHM, ICHi-170336

When I accepted the Black Metropolis Research Consortium’s Archie Motley Archival Internship offer, I had a vague understanding of my project. I was thrilled to be working in a museum for the first time and engaging with work I love—Black stories. At that time, the goal for the Afro-American Patrolman’s League (AAPL) project was to conduct six oral history interviews and at least one transcription by the end of my eight-week program. While I was unable to officially interview former AAPL members over Zoom due to scheduling conflicts, briefly connecting with them and learning pieces of their stories (through phone calls and research) was extremely worthwhile.

For the first few weeks, my primary task was research. My fellow project intern and I gathered as much relevant information on the AAPL as we could find in CHM’s archival materials and additional resources. We read a series of articles discussing policing and Chicago in the 1960s and ’70s. From there we found additional resources overviewing key historical events that directly engaged with Black policing, Chicago policing, and community activism. A few key examples were the assassination of Fred Hampton, the 1968 Democratic National Convention, the trial of the Chicago Seven, and more. Studying the political climate of Chicago helped us develop a framework for understanding the organizational structure of the AAPL. This research bolstered our understanding of the context of potential interviewees and assisted in developing interview questions and strategies to facilitate robust and efficient conversations.

Section from page 1 of an information card for the Fred Hampton Memorial Legal Assistance Scholarship Fund, September 1975. CHM, ICHi-173738-001

In addition to crafting interview questions, we discussed strategies to adapt oral history interviewing to pandemic times. These conversations helped us think differently about how COVID-19 uniquely impacts oral histories that engage with trauma and race-based violence. They reminded me of some impactful encounters I was able to have this summer in the form of informational interviews with CHM staff, where I asked about challenges they face in doing archival work. As with oral history interviews, archivists can encounter sensitive materials from marginalized people that require additional care and consideration.

Project archivist Donna Edgar described her current project as the “the basement mysteries,” which centers on uncovering documents left in the Museum basement. At times she stumbles upon treasures or fragments that belong in a larger collection while at other times, not so much. When I asked her how she stays motivated, she said that while so many “different cultures [have been] lost on the shelf,” her work allows her to unbury them, advocate for them, and help them find a home. Donna’s interview echoed the zest and candor of CHM archivist Angela Solis. Her journey into the world of archives was unexpected, yet in this work she has found immense purpose. Like Donna, Angela sees her work as shining a light on stories that face obstacles in getting onto the shelf: “My vocation is helping those stories get told . . . and helping them last.” While this internship was met with challenges, the connections I made with others led me to think critically not only of the stories we tell but also how we obtain, protect, and remember those stories.

If you were a former member of the African American Patrolmen’s League and would be interested in sharing your story, please contact us at 312-642-4600 or through our Collection Donation Form.