In this blog post, CHM curatorial intern Brigid Kennedy recounts the life of Irene McCoy Gaines as part of a series in which we share the stories of local women who made history in recognition of our online experience: Democracy Limited: Chicago Women and the Vote.

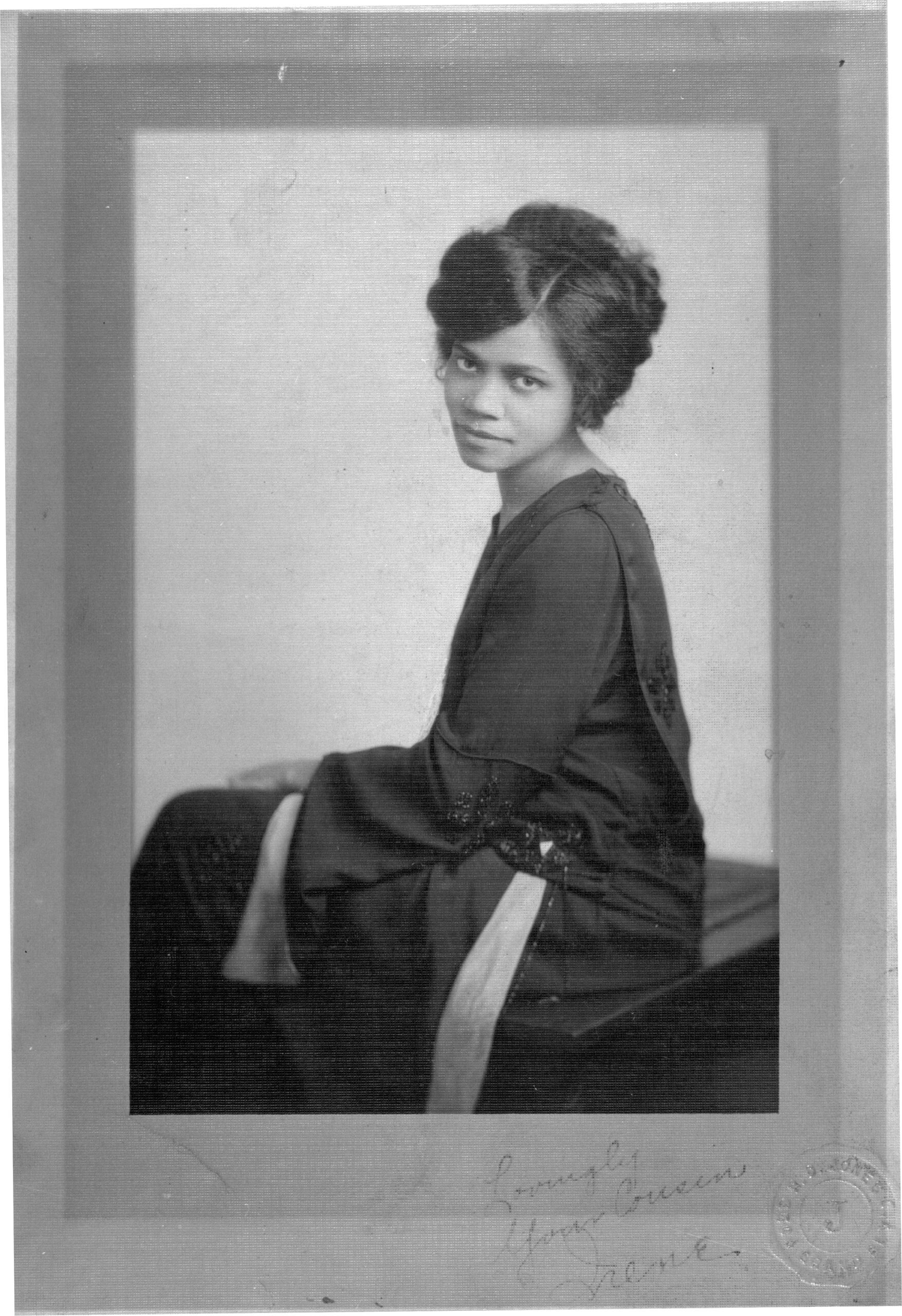

Irene McCoy Gaines devoted her career in politics and advocacy to working against segregation and for the rights of black women. Gaines was born on October 25, 1892, in Ocala, Florida, but moved with her mother to Chicago when her parents divorced. After graduating from high school, she attended Fisk School (a private historically black university, today Fisk University) in Nashville, Tennessee. She graduated in 1910, and years later would continue her studies in social work at the University of Chicago.

Figure 1: Seated portrait of Irene McCoy Gaines. CHM, ICHi-062416

Upon her return to Chicago after college, she discovered that despite her advanced education, job opportunities were severely limited by the discrimination she faced as a black woman. After working as a housekeeper, Gaines found a job as a stenographer at Cook County Juvenile Court. These two early jobs informed her activism for the rest of her life.

Gaines became a member of the Women’s Trade Union League, a national association that supported women in organizing labor unions and improving working conditions, and she recruited other black women for the organization.

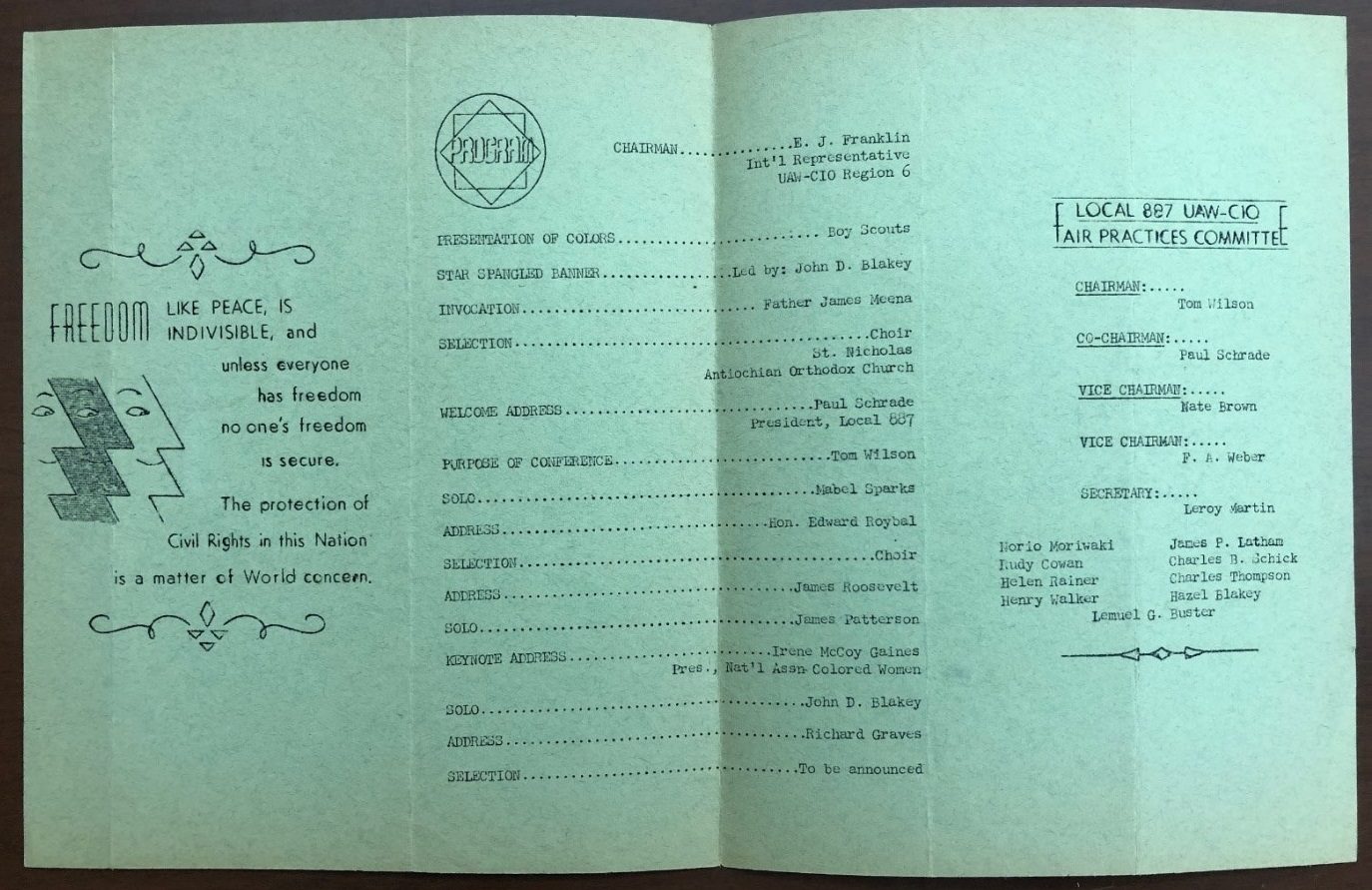

Figure 2: Program for the Local 887 United Auto Workers-Congress of Industrial Organizations Fair Practices Committee Program for Civil Rights & Anti-Discrimination on Sunday, May 2, 1954, at which Gaines delivered the keynote address. Irene McCoy Gaines papers, CHM. Box 4, folder 1.

In 1917, during World War I, she became director of the Girls’ Work Division of the War Camp Community Service program, which connected civilians and soldiers at social events and soldiers to entertainment opportunities in American cities.

Gaines was devoted to the Republican Party of the time, organizing for congressional Republican candidate Ruth Hanna McCormick in 1928 and 1930. She also helped to found and served as president of the Illinois Federation of Republican Colored Women’s Clubs.

In 1931, Gaines was appointed to President Herbert Hoover’s National Committee on Negro Housing, which led to construction of the Ida B. Wells Homes public housing project in the Bronzeville neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago. Gaines herself ran for elected office several times unsuccessfully, often the first black woman to run for a particular office, including for a state legislative seat and for county commissioner’s office, which opened doors for others after her.

Figure 3: Irene McCoy Gaines. CHM, ICHi-030640

Gaines tirelessly advocated for the rights of black women—connecting domestic workers to literacy classes and attempting to overturn unjust convictions of women like Adelaide Lauretta Johnson, who was incarcerated for writing checks with insufficient funds. She worked, too, to ensure that pregnant teenagers had opportunities to continue their educations.

In 1941, Gaines, then president of the Chicago Council of Negro Organizations (CCNO), led a trip to Washington, DC. Members lobbied elected officials and protested racial discrimination in employment and by the Federal Housing Authority, US military, and other governmental organizations. After CCNO’s and other’s activism, Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8802, which was intended to prevent racial discrimination in employment by businesses that held government contracts.

Gaines also was interested in promoting arts and culture. She became a lifetime member of the Art Institute in the late 1920s and founded the “Negro in Art Week” program to support black children who were interested in the arts.

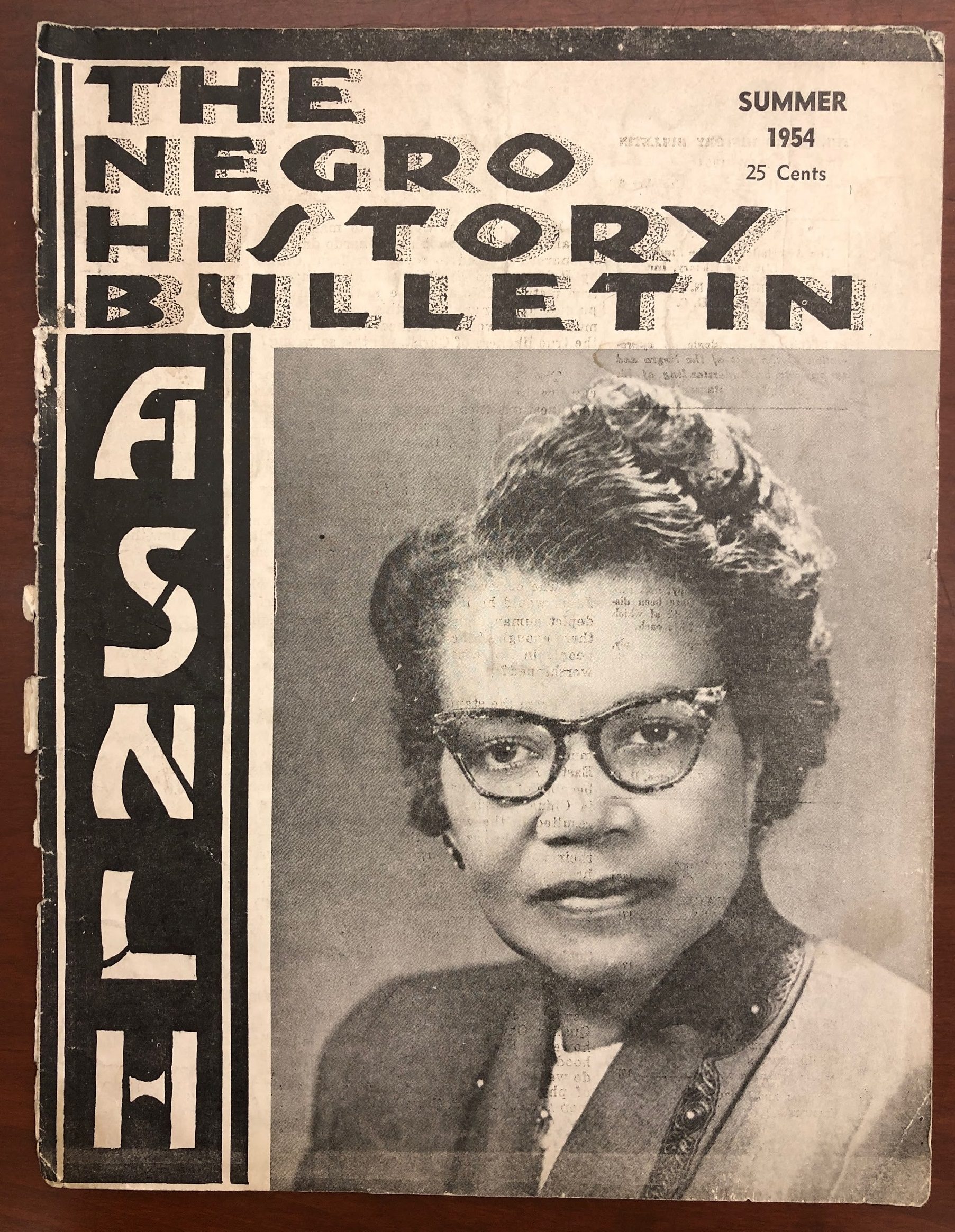

Figure 4: Gaines on the cover of the summer 1954 issue of The Negro History Bulletin. Irene McCoy Gaines papers, CHM. Box 4, folder 1.

In 1953, Gaines co-produced a documentary short about Frederick Douglass, The House on Cedar Hill. It honored among his accomplishments his dedication to women’s rights, and the film won a Freedoms Foundation Award. Gaines died of cancer on April 7, 1964, at age seventy-two, leaving behind a legacy of political and reform work that created new opportunities for black women in Chicago and the nation.

For Educators

Student Reading and Response Guide

Vocabulary

- Advocacy: public support for a cause or policy

- Segregation: the enforced separation of different racial groups

- Discrimination: the unjust treatment of people on the grounds of race, age, gender, or sexual orientation

- Stenographer: a person whose job is to write down speech in shorthand, for example testimony in court

- Indivisible: unable to be divided or separated

Text Questions

- Why do you think working as housekeeper and as a stenographer for Cook County Juvenile Court informed Gaines’ activism?

- What are some examples in the blog of how Gaines worked to end segregation and advance the rights of black women?

- Why do you think Gaines saw the arts as an effective way to communicate the issues she cared about?

Primary Source Analysis: Take a closer look at Figure 2 to answer these questions.

- What 1954 event is this program from? What was Gaines’ role? Why do you think Gaines would have wanted to support this organization?

- This quote appears on the cover of the program: “Freedom like peace, is indivisible, and unless everyone has freedom no one’s freedom is secure.” Do you agree or disagree with this idea? Why? What freedom or civil rights issues are important today?

Journal Prompt

- The blog author, Brigid Kennedy, writes “Gaines herself ran for elected office several times unsuccessfully, often the first black person or black woman to run for a particular office, which opened doors for others after her.” Who has opened doors for you, in your life? How?