In this blog post, CHM curatorial intern Brigid Kennedy recounts the life of labor organizer Lucy Parsons.

The details of Lucy Parsons’s early life in Texas are murky, and she herself provided different accounts of her youth and heritage. Her race was the subject of public debate, but she claimed only Mexican and Muscogee Creek ancestry. These ethnicities, and the popular suspicion that she was at least in part Black, were used in attempts to discredit her politics and activism.

Lucy Parsons in Chicago, 1915. ICHi-027212, Chicago Daily News Negatives Collection, CHM

Parsons was likely born in 1853 and moved to Chicago at age twenty with her new husband, Albert, in the middle of a nationwide economic depression. Chicago was hit hard, still reeling from the Great Fire, and resources were strained. Out of these brutal conditions emerged a labor rights movement, and Lucy and Albert, a Confederate soldier turned radical Republican, quickly established themselves as key figures within it—even opening their home to meetings of the Workingmen’s Party.

When Albert was blacklisted after his involvement in the nationwide strikes of 1877, Lucy opened a dress shop to provide for the family. She then helped organize the Working Women’s Union (WWU), which allowed women who worked as domestic servants, seamstresses, homemakers, and in similar professions to organize. The WWU advocated for women’s labor needs, such as equal pay for equal work and women’s suffrage, though Parsons herself was disillusioned with electoral politics and not active in the suffrage movement. Eventually she stopped working with unions because they focused on reform rather than radical reorganization of society—though she continued to support the working class.

This bomb casing was presented as evidence in December 1887 during the trial of Louis Lingg, one of the eight men accused of homicide after the Haymarket bombing. CHM, ICHi-31957a

On May 4, 1886, Chicago police broke up a gathering in Haymarket Square, which had been called to discuss police brutality in response to labor organizing. Someone in the crowd threw a bomb, which led police to shoot aimlessly into the crowd. Albert Parsons and four other anarchist leaders were ordered to be hanged for having incited the crowds with their speeches, despite a lack of evidence for their involvement in the violence itself.

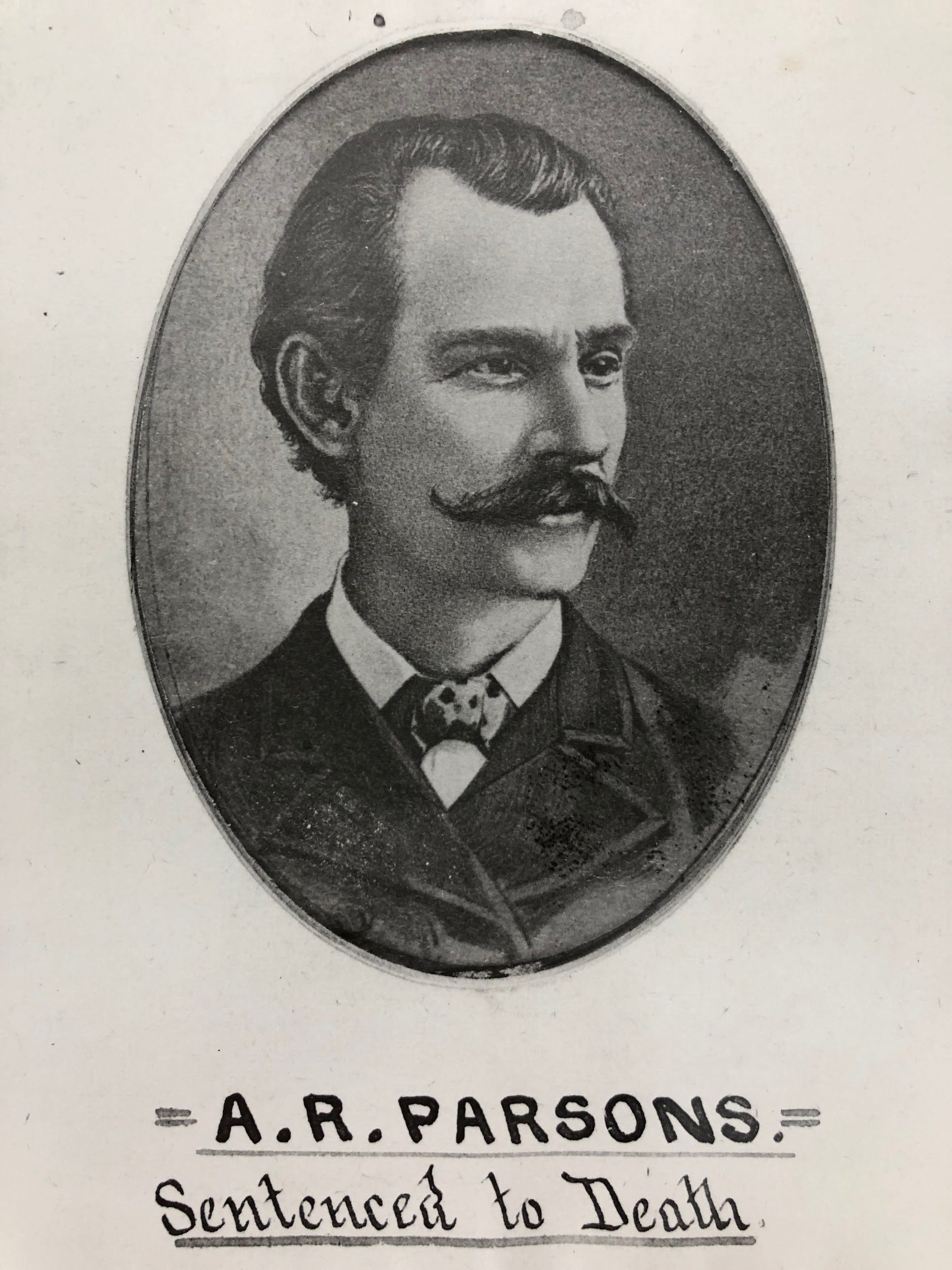

An undated portrait of Albert Parsons with news of his Haymarket sentence. A.R. Parsons, Image file – People P, CHM

After Albert’s death, Parsons devoted herself to publishing on and supporting Chicago’s anarchist movement. She served as editor of the Liberator, an anarchist newspaper, and cofounded a periodical with Lizzie Swank Holmes called Freedom: A Revolutionary Communist-Anarchist Monthly. Here, she found an outlet and an audience for histories of communism, biographies of the Haymarket martyrs, antilynching pieces, and analyses of the oppression of women and of US racism.

Parsons also continued the activism she’d begun before Haymarket. In 1905, she cofounded the Industrial Workers of the World in Chicago with leaders like Mother Jones, Bill Haywood, and Eugene Victor Debs. She continued her activist work, but not without incident. Parsons was arrested after speaking at a meeting of the unemployed on January 17, 1915, and had her bail paid by Hull-House’s Jane Addams. Then, during World War I, and as American fear of communism increased, the US Postal Service refused to send radical publications.

An undated photograph of Parsons pointing to a portrait of Albert in her home in Chicago. Lucy Parsons, Image file – People P, CHM

Despite these obstacles, Parsons continued to work until her death on March 7, 1942, in a house fire. She spent her life challenging oppressive power structures and remains a controversial figure, but one whose actions laid the groundwork for the Chicago we know today.