In part one of this series, project cataloger Emma Florio discusses the process of retroconverting CHM’s small manuscripts collections from catalog cards to digital records. Learn more about her work, which was funded by the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

When I took on this project last summer, the Museum was in the final stage of digitizing the last of its paper card catalog for six thousand small manuscript collections. This involved editing or creating information for these collections, which range in size from a single letter in one folder to dozens of business papers, letters, and receipts spread across multiple folders. The goal was to make each one more accessible and discoverable in ARCHIE, CHM’s online catalog, as well as other library and museum databases, such as WorldCat and the Explore Chicago Collections.

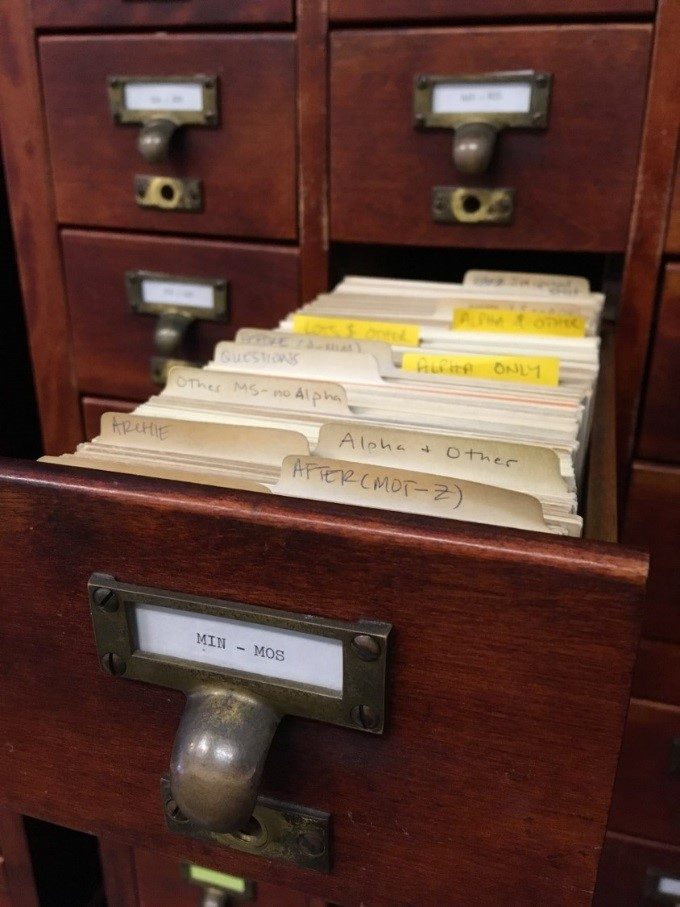

The card catalog in the CHM Research Center. All images by CHM staff.

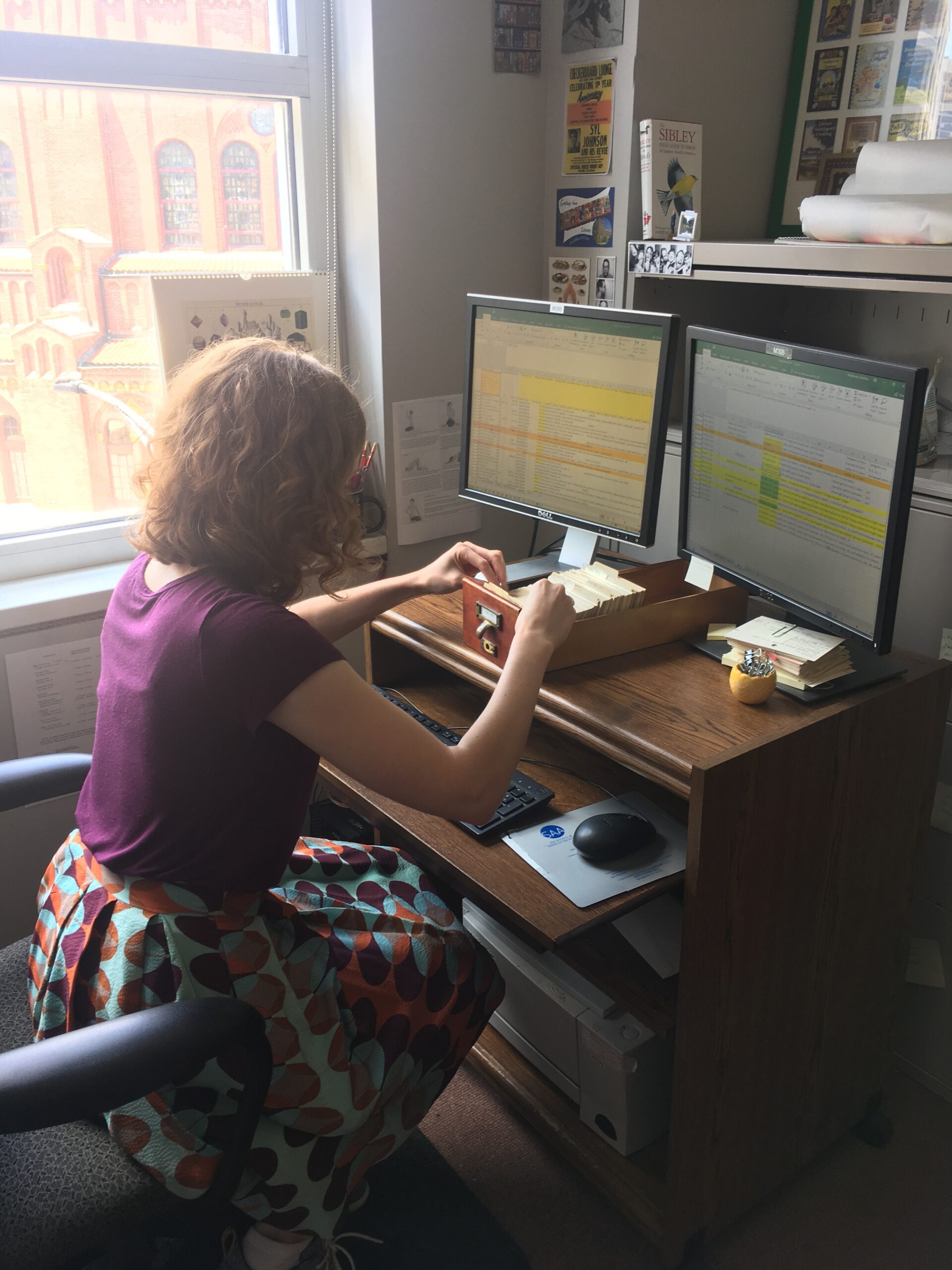

Prior to my arrival, other staff members and many diligent interns had organized the physical catalog card drawers by collection and whether a collection was already in ARCHIE, then entered the information on all of the cards into an Excel spreadsheet. As part of my initial assessment, I looked at the data for every collection and edited it for clarity and ease of use. Sometimes this meant rearranging wording or spelling out abbreviations in compliance with archival standards. It also meant choosing new subject headings to better describe the item. In some cases, when a collection was lacking a catalog card, it meant cataloging the collection from scratch. By the end of April 2019, I had cleaned up the data for more than six thousand collections and performed original cataloging for more than seven hundred collections.

Florio working on transferring data from catalog card to spreadsheet.

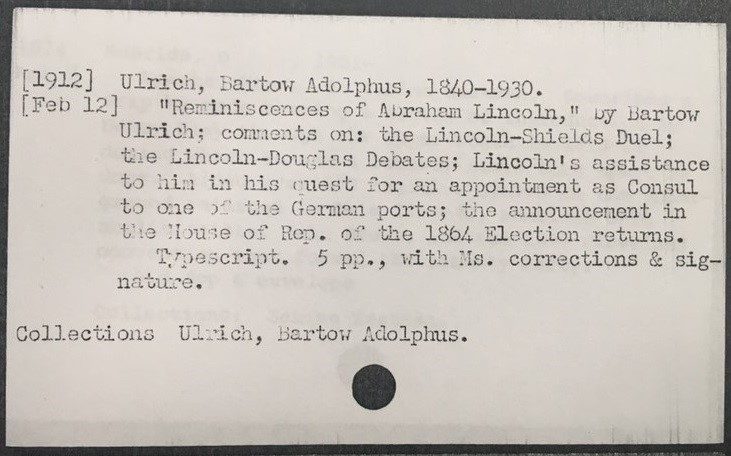

The catalog card for “Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln,” by Bartow Adolphus Ulrich.

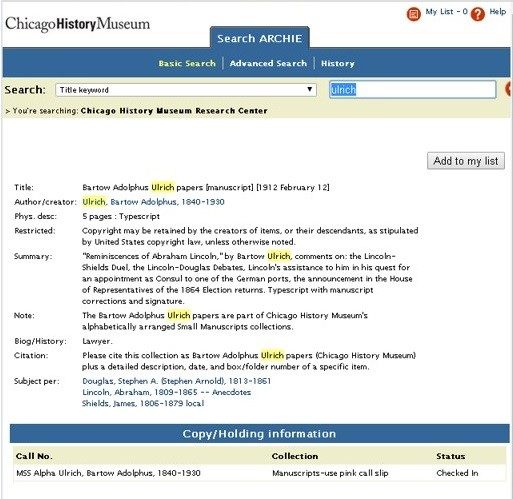

Each column in our spreadsheet corresponds to a different section on the catalog card. In the traditional physical card catalog, there are only so many ways the cards can be organized—only so many different entry points and ways to search for a collection—typically the collection title, author, and maybe the most prominent subjects. In an online catalog, however, with all elements and every word of the catalog record searchable, collections can be discovered in new ways.

The entry for Ulrich’s work in the CHM online catalog.

Even though these collections belong to the Chicago History Museum, the majority are actually not Chicago-related—they were acquired when the Museum’s collecting scope included American history rather than being exclusively Chicago history. This is mainly due to the Charles F. Gunther Collection that the Chicago Historical Society purchased in 1920. Gunther, a German-born confectioner who lived and worked in Chicago at the end of the nineteenth century, collected anything and everything historical—including the first patent issued by the United States (which was signed by George Washington); the table from Appomattox Court House, Virginia, on which General Robert E. Lee signed the terms of surrender for the Civil War; and even skin from the serpent in the Garden of Eden (which, of course, turned out to be fake).

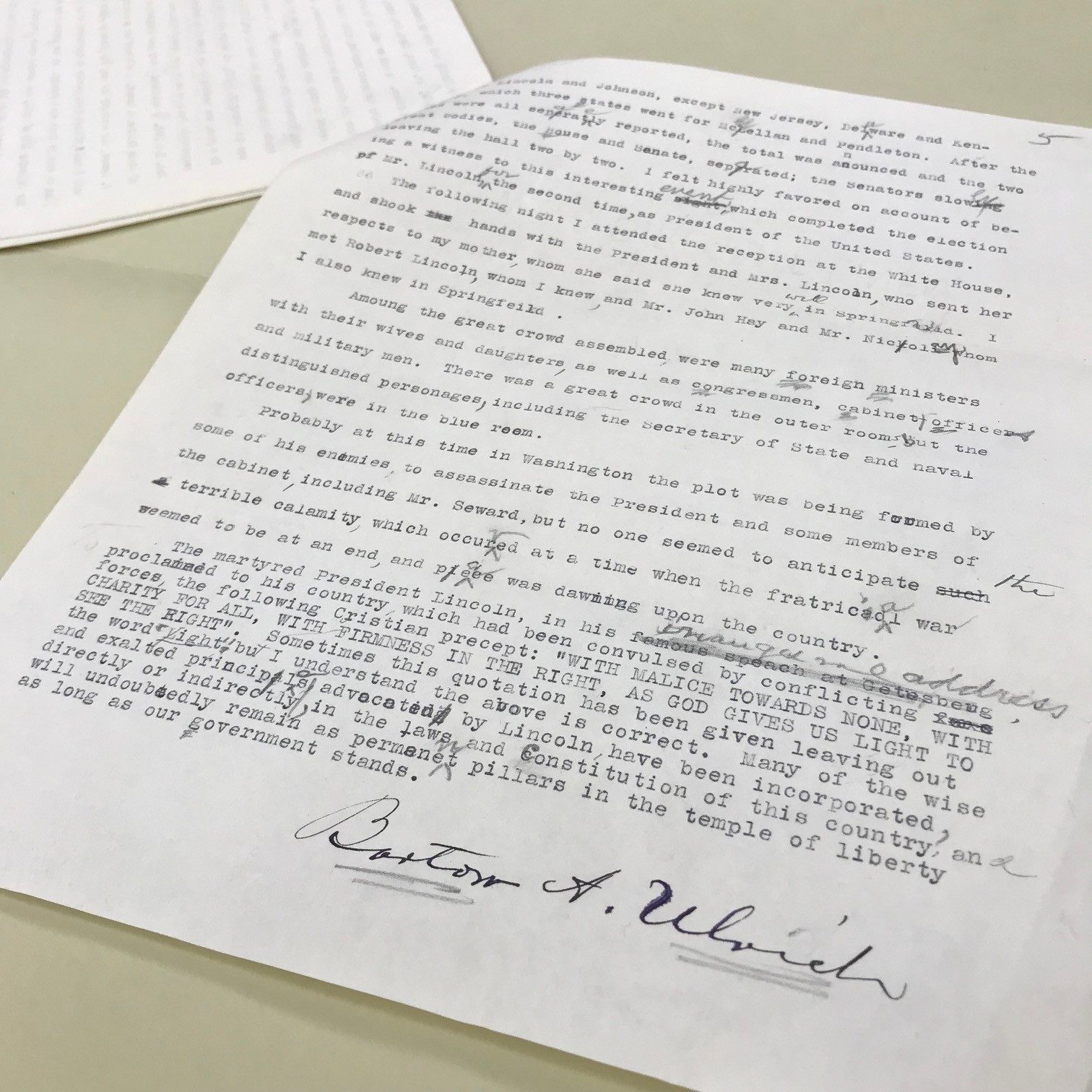

Ulrich’s signed reminiscences with handwritten edits. CHM Small Manuscripts collection

Within the manuscript collections, Gunther items span American history from the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries, which means that the small manuscript topics vary wildly from Colonial America to the Whiskey Rebellion to slavery and the Civil War to Reconstruction and the Gilded Age, Progressive Era, Spanish–American War, and World War I. The Chicago History Museum is thrilled to make all these and more discoverable to an international audience and accessible through the Abakanowicz Research Center.