As part of Monday Night Nitrates, our weekly photograph series, CHM collections staff is blogging about the process of digitizing approximately 35,000 nitrate negatives, a project funded by the Institute of Museum and Library Services. In this post, CHM senior archivist Dana Lamparello writes about making the images discoverable for research.

In many ways, the cataloging step for which I’ve been responsible in our IMLS-funded nitrate preservation workflow bridges the gap between physical and digital, i.e., between the physical nitrate negatives and the digital images and metadata that you’ve been reading about. The ultimate goal of this project is to limit access to the physical nitrate negatives (preservation) while still allowing the negatives to be discoverable for research (access), and it all comes together at this point in the process.

Six of the forty-six boxes of flexible nitrate negatives from the Charles R. Childs collection waiting to be scanned. Photograph by CHM staff

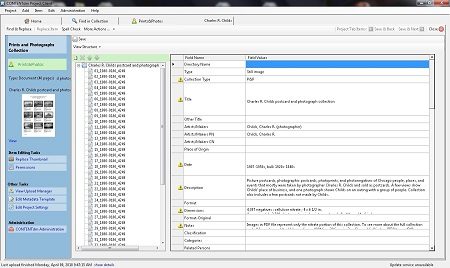

The back end of our ContentDM portal where data and files are added and edited.

First, it’s important to remember that each distinct group of nitrate negatives is considered an archival collection or part of a collection—in some cases, a much bigger collection than what the nitrate portion represents. For example, the Charles R. Childs collection totals nearly ten thousand images, but only about 45 percent of those are nitrate negatives, where the remainder is comprised of postcards, photographic prints, and glass negatives. Certainly all are formats with unique preservation needs but none as pressing as cellulose nitrate. It is important to tie these digitized nitrate images to the greater collection because without it, all context for the images will be lost. The John Walley collection’s nitrates, for example, exclusively document his 1937 Federal Art Project assignment to photograph life and industry in Alaska. The greater Walley collection more comprehensively documents the career of a Chicago-based designer, artist, and professor from 1937 to 1974. Thus, promoting discoverability of the nitrate negatives requires that they remain in context with the rest of the collection for complete understanding.

Childs’s work documented Chicago and the surrounding suburbs in the first half of the twentieth century, such as this image of Wacker Drive, c. 1925. CHM, ICHi-095740

In this photograph, Walley captured a worker unloading fish onto a boat, c. 1937. CHM, ICHi-094214

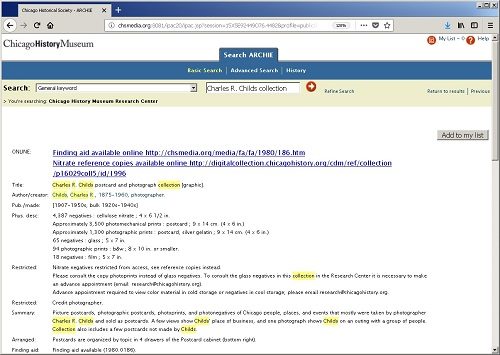

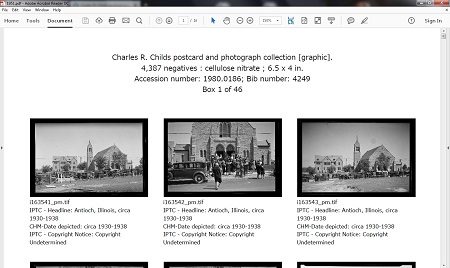

Like the Walley collection, most of the nitrates I encountered already correspond to a record in our library online catalog ARCHIE, which is the main access point and database to search all of our research collection holdings, including our photographic archival collections. ARCHIE records include summaries of each collection and with larger collections like Walley’s, a finding aid is available. Unlike the ARCHIE record, the finding aid provides more detailed information about the collection, mainly an inventory of each box or folder and details about what they contain. In addition to updating the information in ARCHIE records and finding aids to reflect the work completed for this project, including edits to the collection descriptions and adding data about the IMLS grant, restriction notes about access to the physical negatives, and new freezer storage locations, I also added a link to a separate inventory—one that details the nitrates. This visual inventory, as we call it, is simply a PDF with thumbnail-sized images of each digitized nitrate negative and very minimal metadata, including description, date, and copyright status evaluated by our Rights and Reproductions manager and utilizing standard rights statements from RightsStatements.org.

The collection-level ARCHIE record with links to the finding aid and nitrate PDF for the Charles R. Childs collection.

Researchers can quickly scan the PDF to search the collection.

The PDF is a means of quickly glancing through these images. Should you need to see a higher resolution image for your research, it is available upon request, but providing this quick view of the images allows you to see them in context with the rest of the collection, especially when the rest of the collection isn’t digitized.

Join the Discussion