Chicago is where the first in a long line of achievements in LGBTQIA+ rights took place. CHM senior public and community engagement manager Gregory Storms writes about the very first LGBTQIA+ rights organization in the United States.

In 1962, Illinois became the first state to decriminalize consensual same-sex sexual relations—41 years before it would be decriminalized nationally. But long before this, Chicago can boast another incredibly important first in queer history: the founding of the Society for Human Rights (SHR). Established a century ago on December 10, 1924, by Henry Gerber (1892–1972), SHR grew out of years of international scientific research and public dialogue about homosexuality.

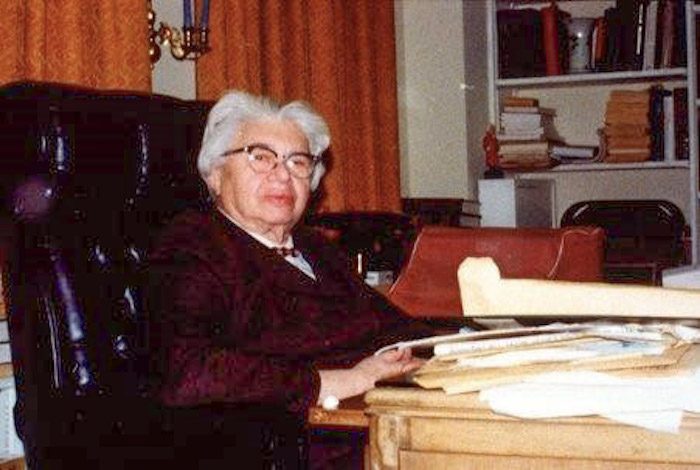

Portrait of Henry Gerber, c. 1930. CHM, ICHi-024893

The SHR drew considerable inspiration from foundational German sexologist and advocate for LGBTQIA+ people, Magnus Hirschfeld (1868–1935), who also happened to spend time in Chicago in 1893 during the World’s Columbian Exposition.

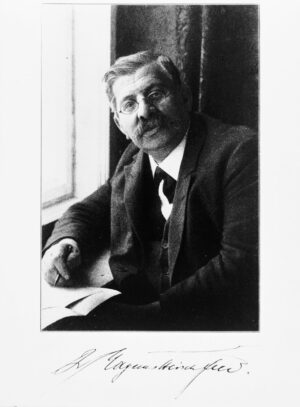

Seated portrait of Magnus Hirschfeld, November 12, 1927. US Holocaust Memorial Museum; courtesy of Magnus-Hirschfeld Gesellschaft

During this time, Hirschfeld came upon Chicago’s homosexual subculture, launching his professional trajectory into the field of the science of sexuality. Several years later, back in Berlin, Hirschfeld founded the Wissenschaftlich-humanitäres Komitee (WhK, Scientific-Humanitarian Committee), which advocated for the recognition and legal status of LGBTQIA+ people. Nearly two decades later, Hirschfeld founded the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft (Institute for Sexual Science), the world’s first sexology research center, which also advocated for LGBTQIA+ rights on scientific grounds. It would last until 1933 when its library and archives were destroyed in book burning efforts by the Nazi Party.

Gerber was profoundly inspired by Hirschfeld’s work. Having read related publications from the German Homosexual Emancipation Movement of the early twentieth century, Gerber felt that one way to support the deeply oppressed homosexual community was to create and distribute the first known US publication created for other homosexuals called Friendship and Freedom. To receive such a newsletter at this time, however, was a dangerous proposition for many, as it would have been illegal to mail or possess it under the Comstock Act. Therefore, Friendship and Freedom had a very small readership and lasted just two issues.

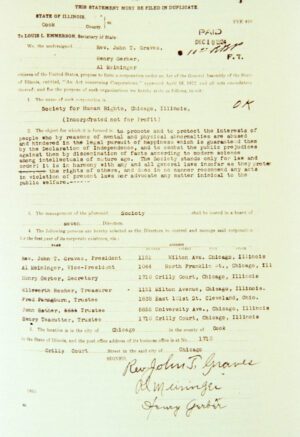

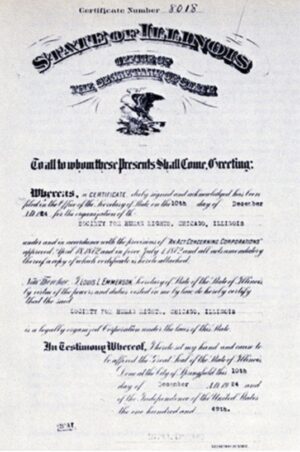

Document establishing the Illinois charter of Society of Human Rights, December 10, 1924. 1987.627 B1, Gregory Sprague papers [manuscript], 1972–1987. CHM, ICHi-039678

Formally recognized with an official State of Illinois Charter on Christmas Eve that year, SHR was sadly short-lived. Limited to only homosexual, cisgender men, SHR prohibited bisexual men from joining the organization.

The Society for Human Rights full charter document, granted by the State of Illinois on December 24, 1924. The Legacy Project

However, SHR’s vice president, Al Weininger, was married to a woman, and she eventually tipped off the SHR’s existence, leading to the group’s downfall. Gerber was arrested in 1925 and was reported in the Chicago Examiner in a story titled “Strange Sex Cult Exposed.” Charges against Gerber were later dismissed since he was arrested without a warrant. Still, as was common, Gerber lost his life savings, his job with the Post Office, and he soon left Chicago for New York City where he served in the US Army until being honorably discharged seventeen years later.

The residence at 1710 North Crilly Court is in Chicago’s Old Town neighborhood, about half a mile away from the Museum. National Park Service; courtesy of Shirley and Norman Baugher

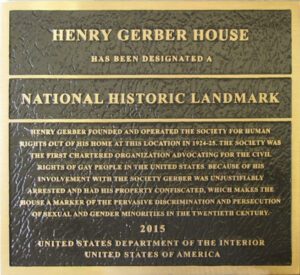

In Chicago, we celebrate the legacy of the SHR and Henry Gerber in several ways. Gerber’s house was named a Chicago Historic Landmark in 2001 and a National Historic Landmark in 2015. The Gerber/Hart Library and Archives, named partly in honor of Gerber, remains Chicago’s primary resource for LGBTQIA+ related collections.

The National Historic Landmark plaque at Gerber’s former residence. National Park Service; photograph by NPS staff

Despite the short life of the Society for Human Rights, it remains a first in US queer history. It would be two decades until we saw similar, more widely recognized LGBTQIA+ right organizations like the Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis take hold to shape the future of the fight for equality.

Bibliography

Andries, Daniel, Alexandra Silets, and Jane Lynch. Out & Proud in Chicago. Window to the World Communications, Inc, 2008.

Bauer, Heike. The Hirschfeld Archives: Violence, Death, and Modern Queer Culture. Temple University Press, 2017.

Bullough, Vern L. Science in the Bedroom: A History of Sex Research. Basic Books, 1994.

Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame. “Henry Gerber.” Accessed December 3, 2024.

De la Croix, St. Sukie. Chicago Whispers: A History of LGBT Chicago Before Stonewall. University of Wisconsin Press, 2012.

Elledge, Jim. The Boys of Fairy Town: Sodomites, Female Impersonators, Third-Sexers, Pansies, Queers, and Sex Morons in Chicago’s First Century. Chicago Review Press, 2018.

Francis, Meredith. “The Chicagoan Who Founded the Earliest Gay rights Group in America.” WTTW. Accessed December 3, 2024.

Gerber, Henry. “The Society for Human Rights – 1925.” One, September, 1962. Accessed December 3, 2024.

Nash, Carl. “Gay and Lesbian Rights Movement.” Encyclopedia of Chicago. Accessed December 3, 2024.

Johnson, David K. “The Kids of Fairytown: Gay Male Culture on Chicago’s Near North Side in the 1930s.” In Creating a Name for Ourselves: Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Community Histories, edited by Brett Beemyn. Routledge, 1997.

Katz, Jonathan Ned. “Henry Gerber: Gay Pioneer.” In Out and Proud in Chicago: An Overview of the City’s Gay Community, edited by Tracy Baim. Surrey Books, 2008.

Legacy Project. “Henry Gerber – Nominee.” Accessed December 3, 2024.

Legacy Project. “The Society for Human Rights.” Accessed December 3, 2024.

National Park Service. “LGBT Activism: The Henry Gerber House, Chicago, IL.” Accessed December 3, 2024.